뒤를 돌아보고 앞으로 나아가기: 의과대학 1학년의 포트폴리오 글쓰기에 대한 메타-성찰(Acad Med, 2018)

Looking Back to Move Forward: First-Year Medical Students’ Meta-Reflections on Their Narrative Portfolio Writings

Hetty Cunningham, MD, Delphine Taylor, MD, Urmi A. Desai, MD, MS, Samuel C. Quiah, MSW, Benjamin Kaplan, Lorraine Fei, MPH, Marina Catallozzi, MD, MSCE, Boyd Richards, PhD, Dorene F. Balmer, PhD, and Rita Charon, MD, PhD

의학 교육자들은 종종 [성찰적인 글쓰기]를 성찰적 능력을 배양하고 유능하고 동정심 있는 의사들의 전문적 정체성 구축을 촉진하는 귀중한 도구로 언급한다. 일상적인 의학 교육의 엄격함은 종종 학습자들이 그들이 어떤 사람이 되고 있는지에 대한 종적인 관점을 얻는 것을 방해한다. 훈련 중에 번아웃의 상당한 위험과 공감의 감소를 고려할 때, 학생들이 성찰 능력을 육성하는 데 도움을 줄 필요성은 특히 두드러진다. 게다가, 현재 [표준화와 역량의 문서화]에 초점을 맞추고 있는 것은 개인의 재능, 가치, 목표의 개인적 평가를 떨어뜨림으로써 [전인적 직업적 정체성]의 구축에 도전하거나 심지어 대항할 수 있다 —성찰을 지원하기 위한 의도적인 노력이 더욱 필요합니다.

Medical educators frequently cite reflective writing as a valuable tool to foster reflective capacity and to promote construction of a professional identity in competent and compassionate doctors.1–6 The day-to-day rigors of medical education often preclude learners from gaining a longitudinal perspective on who they are becoming. The need to aid students in fostering reflective capacity is particularly salient given the significant risks of burnout and a decrease in empathy during training.7–9 Furthermore, the current focus on standardization and documenting competency may challenge or even counteract the construction of a holistic professional identity by devaluing individuation of personal talents, values, and goals—which, in turn, renders intentional efforts to support reflection all the more necessary.10–13

비록 전세계의 의대들이 이러한 많은 문제들을 해결하는 수단으로 성찰적인 글쓰기를 받아들였지만, 일부 교육자들은 [글쓰기 커리큘럼]이 [역량을 문서화하도록 구조화]되거나, 학생들의 노력이 [환원주의적 관점으로 평가될 때] 성찰 능력을 육성하려는 노력이 역효과를 낼 수 있다는 우려의 목소리를 냈다. 실제로, Ng와 동료들은 전통적인 의료 기관의 "지배적 인식론적 렌즈"와 일치하는 공리적 결과를 제공하기 위해 반사적 글쓰기를 사용할 때의 잠재적인 함정을 웅변했다. 이러한 위험으로부터 보호하기 위해 일부 의학 교육자들은 [서사 의학적 전통에 앵커링된 성찰 도구]를 학생들이 효과적으로 성찰 능력을 개발하고 전체론적인 전문적 정체성을 구축할 수 있는 "개방된 교육 공간"을 육성하는 데 이상적으로 적합한 것으로 보았다.

Although medical schools around the globe have embraced reflective writing as a means of addressing many of these issues,14 some educators have voiced concerns that efforts to foster reflective capacity may be counterproductive when writing curricula are structured to document competencies or when student efforts are evaluated with a reductionist lens.14,15 Indeed, Ng and colleagues15 eloquently described potential pitfalls of using reflective writing to serve a utilitarian outcome consistent with the “dominant epistemological lens” of traditional medical institutions. To protect against these risks, some medical educators have looked to reflective tools anchored in the narrative medicine tradition as ideally suited to foster “open educational spaces,” sometimes called “reflective spaces,” wherein students may effectively develop their reflective capacity and construct a holistic professional identity.16,17

서사 의학

Narrative Medicine

[서사 의학 프레임워크] 내에서, [성찰적 공간]은 [엄격한 교육학적 행동 순서]를 통해 만들어진다. 참가자들은 [창의성과 세부사항]에 대한 관심을 증진시키는 [텍스트 작품을 공유하는 것]으로 시작한다. [공유된 읽기와 해석]은 그룹 내 신뢰를 강화합니다. 다음으로, 읽기를 반향echo하는 [개방형 프롬프트에 대한 응답]으로 글쓰기는 의대생들이 [결정적이고 증거에 기초한 답을 제공하는 것]에서, [실존적이고 모호한 질문을 숙고하는 것]으로 [환원주의]에서 보다 [확장적인 사고 방식]으로 전환하도록 장려한다. 그리고 나서, 참가자들이 방금 [쓴 것을 큰 소리로 읽고 듣는 것]은 서로의 글에 반응하는 것과 함께, 안전과 상호 존중의 분위기에서 창의적인 글의 발견 가능성에 대한 깊은 존경심을 불러일으킨다.

Within a narrative medicine framework, reflective space is created through a rigorous sequence of pedagogical actions.18 Participants start with a shared close reading of textual works that promote creativity and attention to detail. The shared reading and interpreting enhance trust within the group. Next, writing in response to open-ended prompts that echo the reading encourages medical students to shift from a reductionist to a more expansive way of thinking, from providing definitive, evidence-based answers to pondering existential and ambiguous questions. Then, reading aloud and listening to what participants have just written, along with responding to one another’s writing, inspires deep respect for the discovery potential of creative writing within a climate of safety and mutual respect.18

내러티브 포트폴리오 개발

Development of a Narrative Portfolio

컬럼비아 대학교 Vagelos 의과대학(P&S)의 교육자들은 학생들이 성장하고 공유할 수 있는 안전하고 목적이 있는 탐구적인 성찰 공간을 제공하기 위해 이러한 서사 의학 개념을 통합한 종단적 성찰적 글쓰기 포트폴리오(아래 설명)를 개발했다. 종단적 관점를 향상시키고, 이 포트폴리오 내에서 성찰적 쓰기의 이점을 높이기 위해 Signature Reflection이라는 학기말 메타 성찰 과제를 설계했다. 매 학기마다, [시그니처 리플렉션 과제]는 학생들이 [포트폴리오 항목의 아카이브를 검토]하고, 이전 글에서 [자신에 대해 알게 된 것]에 대해 쓰고, 이 연습을 통해 [자신의 과거와 미래의 자신이 연결]되도록 촉구한다. 이 글은 우리 학교의 종단적 글쓰기 포트폴리오가 만들어낸 '반사적 공간'에 대한 이론적 근거와 교육과정 내용, 그리고 초기 분석에 초점을 맞추고 있다.

Educators at the Columbia University Vagelos College of Physicians and Surgeons (P&S) have developed a longitudinal reflective writing portfolio (described below), incorporating many of these narrative medicine concepts, to provide a safe, purposeful, exploratory reflective space in which students may grow and share. To enhance the longitudinal scope and to augment the benefits of reflective writing within this portfolio, we designed an end-of-semester meta-reflection assignment called the Signature Reflection. Each semester, the Signature Reflection assignment prompts students to review their archive of portfolio entries, to write about what they notice about themselves in their previous writing, and through this exercise, to connect with their former and future selves. This article focuses on the rationale, curriculum content, and early analysis of the “reflective space” created by our school’s longitudinal writing portfolio.

의대 1학기 후 학생들이 작성한 [시그니처 리플렉션]에 대한 우리의 분석은 포트폴리오에 표현된 대로 의대 여정에 대한 학생들의 관점을 보여주는 독특한 창을 제공했다. 우리는 학생들이 자신의 글을 돌아볼 수 있는 기회가 주어졌을 때 그들 스스로 무엇을 볼 수 있는지 배우고 싶었다. 우리는 또한 그들의 말이 포트폴리오의 학습 결과를 밝힐 수 있는지, 그리고 만약 그렇다면, 어떻게 밝혀질지 알고 싶었다. 마지막으로, 우리는 학생들이 전문적인 정체성 구축을 탐구하기 위해 포트폴리오를 사용하는지, 그리고 만약 그렇다면, 어떻게 사용하는지를 이해하고 싶었다.

Our analysis of Signature Reflections written by students after their first semester of medical school offered a unique window into the students’ perspectives on their own medical school journeys as expressed in their portfolios. We wanted to learn what students themselves would see when given the opportunity to look back on their own writings. We also wanted to learn whether their words might shed light on the learning outcomes of the portfolio, and if so, how. Finally, we wanted to understand if students used the portfolio to explore professional identity construction, and if so, how.

맥락

Context

20년 이상 P&S 의대생들은 서사의학 프로그램을 통해, 인문학 내 창의적이고 탐구적인 세미나를 선택하고 참여하도록 했다. 시각적 작업이든 서면 작업이든, 학생들은 부분적으로 이러한 경험에 대해 글을 썼는데, 이는 그들이 면밀한 관찰과 정확하고 상세한 표현의 기술을 강화할 수 있고, 이는 결과적으로 환자 및 동료들에게 참여하고 심지어 연결하는 능력을 강화할 수 있다. P&S 서사의학 선택지에 대한 질적 분석은 학생들이 미래의 의사로서 훈련과 성장에 있어 서사의학의 역할을 인식하고 높이 평가하는 것으로 나타났다.

For more than 20 years, through the narrative medicine program, medical students at P&S have been required to select and participate in creative and exploratory seminars within the humanities. Whether responding to visual or written works, students have written about these experiences, in part so that they might strengthen their skills of close observation and accurate and detailed representation, which can, in turn, deepen their capacity to attend to and even connect with patients and peers. Qualitative analysis of the P&S Narrative Medicine selectives has indicated that students recognize and appreciate the role of narrative medicine in their training and growth as future physicians.4,19,20

의과대학의 사회적, 행동적, 인문학적, 예술적 교육과정을 향상시키기 위한 [국립보건원 지원 프로젝트]의 맥락에서, 2011년 교수진과 학생들로 구성된 태스크포스가 소집되어, [서사 의학적 전통의 방법]을 사용하여 교육과정 전반에 걸쳐 [성찰적 글쓰기를 증가시키는 방법]을 모색했다. 그 목적은 학생들에게 시간이 지남에 따라 [그들이 되어고 있는 전문직]에 대한 미묘한 시각을 제공하는 것이었다. 그 특별 위원회는 반성문에 관한 문헌을 검토하고 동료 기관들의 경험을 조사하기 위해 1년 동안 매월 만났다. 태스크 포스는 적절한 텍스트와 프롬프트의 선택, 학생 참여 및 신뢰 유지(특히 개인 정보 보호 문제를 고려할 때), 교수진 훈련 및 평가 메커니즘을 고려했다. 결과적으로, 2013년에, P&S는 1년간의 자발적인 파일럿 프로그램에서 배운 후, 들어오는 모든 의대생들을 위한 성찰적인 글쓰기 포트폴리오 요건을 시작했다. 태스크포스는 포트폴리오가 다음을 할 것을 기대했다.

- 기관이 과거에 서사의학으로 성공했던 경험을 활용하고,

- 학생들이 종단적 글쓰기 커리큘럼의 혜택을 받을 수 있도록 하고,

- 학생들에게 시간이 지남에 따라 그들이 어떤 사람이 되고 있는지에 대한 개인화된 관점을 제공한다.

In the context of a National Institutes of Health–supported project to enhance the social, behavioral, humanities, and arts curricula in the medical school, a task force of faculty and students convened in 2011 to look for ways to increase reflective writing throughout the curriculum using methods from the narrative medicine tradition. The aim was to provide students with a nuanced view, over time, of the professionals they are becoming. The task force met monthly for a year to review the literature on reflective writing and to examine peer institutions’ experiences. The task force considered the selection of appropriate texts and prompts, the maintenance of student engagement and trust (especially given privacy concerns), faculty training, and a mechanism for evaluation. As a result, in 2013, after learning from a one-year voluntary pilot, P&S launched a reflective writing portfolio requirement for all incoming medical students. The task force hoped the portfolio would

- capitalize on the institution’s prior success with narrative medicine;

- allow students to benefit from a longitudinal writing curriculum; and

- offer students an individualized view, over time, of who they are becoming.

P&S 포트폴리오

The P&S portfolio

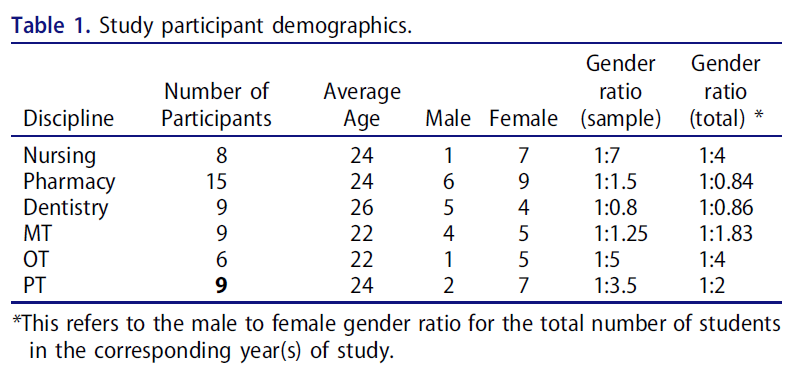

전임상에서 [임상 사회 및 행동 과학]과 [핵심 임상 기술]에 초점을 맞춘 P&S 과정인 Foundations of Clinical Medicine(FCM)에 뿌리를 둔 포트폴리오 목표는 [학생들의 성찰 능력을 강화]하고, [전인적 전문적 정체성의 구축을 촉진]하는 것이다. 이를 위해서는 다양한 기회를 제공하는 종단적 프로그램을 통해, 학생들은 동료와 교수진-학생들의 의견을 반영하여 [유도된 성찰]에 참여하도록 합니다. 우리는 표 1에 포트폴리오의 주요 기능을 설명합니다.

Rooted within Foundations of Clinical Medicine (FCM), a P&S course focused on preclinical social and behavioral sciences and on core clinical skills, the portfolio goals are to reinforce students’ reflective capacity and to foster the construction of a holistic professional identity through a longitudinal program that offers multiple occasions for students to engage in guided reflections with input from peers and faculty–mentors. We describe key features of the portfolio in Table 1.

포트폴리오의 목적이 [글쓰기에서 성찰을 보여주는 것]이 아니라, [글쓰기를 통해 성찰을 배우는 것]이기 때문에, 출품작은 대부분 편집되지 않은 [강의식 서사 의학 연습]이다. 추가적인 글쓰기 프롬프트는 학생들이 시체를 처음 만난 후에 작성된 성찰부터 초기 임상 경험에 대한 고려사항까지 다양하다. 학생들은 포트폴리오 작성 항목을 대학 포트폴리오 웹사이트에 업로드합니다. 학생들은 3학기마다 최소 6개의 글쓰기 항목과 1개의 학기말 메타성찰문을 제출한다; 이후 임상실습생 자격으로 계속 입력해야 합니다. 교수진은 학생들이 P&S에서 학부 의학 교육을 받는 동안 추가적인 자발적인 참가를 제출하도록 장려한다.

Because the purpose of the portfolio is to learn reflection through writing, as opposed to the goal of demonstrating reflection in writing, entries are mostly in-class, unedited narrative medicine exercises. Additional writing prompts are diverse, ranging from reflections written after the students first meet their cadavers to considerations of their early clinical experiences. Students upload their portfolio writing entries to a university portfolio website. Students submit at least six writing entries and one end-of-semester meta-reflection during each of three preclinical semesters; entries continue during subsequent clinical clerkships. Faculty encourage students to submit additional voluntary entries throughout their undergraduate medical education at P&S.

[교실에서 연습할 때 사용되는 서사적 의학 방법]은 다른 곳에서 잘 설명되었다. 간단히 말해, [서사 의학 전통을 훈련]받은 FCM [교수진-멘토]들이 이끄는 [12~14명의 학생들]로 구성된 [소규모 그룹]이 복잡한 문학 텍스트에 대한 [긴밀한 독서와 토론]에 함께 참여한다. 교수진은 진행 중인 과정 주제(예: 임상적 만남에서 여러 관점에 대한 인식)와 암묵적으로 일치하기 위해 학생들의 의대 경험의 아크arc와 유사한 서사적 텍스트를 선택한다. 단, 교직원은 학생들에게 [커리큘럼 및 주제 관련성을 설명하지 않는다]; 오히려, 학생들은 [텍스트에 대한 그들만의 관찰과 해석]을 하고, 그들이 [알아차린 것을 명확하게 하고 해석하는 연습]을 하도록 장려된다.

The narrative medicine method used during in-class exercises has been well described elsewhere.18,21 Briefly, small groups of 12 to 14 students, led by FCM faculty–mentors who are trained in the narrative medicine tradition, engage together in close reading and discussion of complex literary texts.3 Faculty select the narrative texts, which parallel the arc of students’ medical school experiences, for their implicit congruence with the ongoing course themes (e.g., awareness of multiple perspectives in a clinical encounter). However, faculty do not explicate the curricular and thematic connections for students; rather, students are encouraged to make their own observations and interpretations of the text, and to practice articulating and interpreting what they notice.

학생들의 관찰력과 서술력을 높이기 위해, 소그룹 토론은 [형태, 시간, 은유, 분위기]와 같은 장치에 초점을 맞춘다. 이 토론에 이어, 학생들은 그들 자신의 [창의적이고 독특한 성찰을 장려]하기 위해 고안된 [개방형 프롬프트에 대한 개별 응답]을 작성한다. 마지막으로, [글을 쓴 후]에, 학생들은 그들의 [작품을 서로 공유]할 기회를 갖는다. 예를 들어 윌리엄 카를로스 윌리엄스의 짧은 시 '아티스트'(부록 1 참조)에 초점을 맞춘 세션에서 학생들은 등장인물들의 관계와 설정에 대한 질문을 곰곰이 생각하고 토론한다. 그 시에 나오는 사람들은 누구인가요? 그들은 서로에게 누구인가? 내레이터는 누구입니까? 무슨 일이야? 분위기가 어때요? 다음으로, 그들은 ["예상치 못한 아름다움의 순간에 대해 써라"라는 메시지에 대답]한다. 10분 이내로 글을 쓴 후, 학생들은 그들이 쓴 것을 짝을 지어 읽거나 더 큰 그룹과 함께 읽도록 하고, 공유된 글에 응답한다. 모범적인 학생 포트폴리오 응답은 부록 1을 참조하십시오.

To heighten students’ observational and descriptive capacities, small-group discussions focus on such devices as form, time, metaphor, and mood. Following this discussion, students write individual responses to open-ended prompts designed to encourage their own creative, unique reflections. Finally, after writing, students have the opportunity to share their work with one another. For example, during a session focused on “The Artist,”22 a short poem by William Carlos Williams (see Appendix 1), students ponder and discuss questions about the relationships of the characters and the setting. Who are the people in the poem? Who are they to one another? Who is the narrator? What is going on? What is the mood? Next, they respond to the prompt “Write about a moment of unexpected beauty.” After writing for no more than 10 minutes, students are invited to read what they wrote, either in pairs or with the larger group, and respond to the shared writing. See Appendix 1 for an exemplar student portfolio response.

학생들은 매 학기마다 [1~2개의 서사 의학 항목]과 [시그니처 리플렉션]을 교수진(멘토 또는 멘토)에게 제출해야 하지만, 학생이 FCM 교수진을 초청하지 않는 [한 대부분의 항목은 비공개]로 유지된다. 멘토 피드백은 평가적이지 않고, 대신 학생들이 배우고 있는 것을 모델링하는 관찰과 설명의 유사한 면밀한 읽기 방법에 의존한다. (이러한 방법은 다른 곳에서 자세히 설명합니다.) FCM 교수진-멘토들은 1학년 학생들의 남은 의과대학 기간 동안 동행하며, 그들의 서면 피드백은 매 학기 개별 멘토링 회의의 기초를 제공한다.

Students must submit 1 to 2 narrative medicine entries and their Signature Reflection to their faculty–mentor each semester; however, most entries remain private unless a student invites the FCM faculty–mentor to provide commentary. Mentor feedback is not evaluative but instead relies on similar close reading methods of observation and description that model what the students are learning. (These methods are described in detail elsewhere.3) FCM faculty–mentors accompany their first-year students through their remaining years of medical school, and their written feedback provides the basis for individual mentoring meetings each semester.

시그니처 리플렉션

Signature Reflections

P&S 포트폴리오의 중요하고 혁신적인 구성 요소 중 하나는 [시그니처 리플렉션]입니다. 매 학기가 끝날 때마다 학생들은 20분간의 강의실 시간을 갖고, 포트폴리오 전체 항목을 읽는다. 그리고 나서, 그들은 그들 자신의 이전 글들에 면밀한 관찰과 묘사의 동일한 서술적 의학 도구들을 적용하도록 격려하는 프롬프트에 대한 응답으로 '시그니처 리플렉션'을 쓰는데 10분에서 15분을 보낸다. 이러한 방식으로, [시그니처 리플렉션]은 학생들이 [자기 인식을 위한 노력의 증거]를 찾기 위해, [자신의 글을 조사]하고, [의대에서 경험한 것에 대한 가설]을 세우고, [자신에 대해 알아차리는 것에 대한 결론을 도출]할 수 있는 기회를 제공한다. 이 연습은 학생들이 [그들이 쓴 것을 돌아봄]으로써 그들 자신에 대한 더 큰 이해를 얻을 수 있는 메커니즘을 제공한다.

One important and innovative component of the P&S portfolio is the Signature Reflection. At the end of each semester, students have 20 minutes of classroom time to read their entire collection of portfolio entries. Then, they spend 10 to 15 minutes writing a Signature Reflection in response to a prompt that encourages them to apply the same narrative medicine tools of close observation and description to their own previous writings. In this way, the Signature Reflection provides an opportunity for students to plumb their own writing for evidence of their efforts at self-recognition, to frame hypotheses about what they have experienced in medical school, and to draw conclusions about what they notice about themselves. This exercise offers a mechanism by which students may gain a greater understanding of themselves by looking back at what they have written.

학생 글쓰기 분석

Analysis of Student Writing

2015년 1월, 우리는 P&S 포트폴리오가 학생들의 [성찰 능력]과 [전인적 전문직 정체성의 구성]에 미치는 영향을 이해하기 위해 시그니처 리플렉션을 분석했다.

In January 2015, we analyzed Signature Reflections to understand the effect of the P&S portfolio on students’ reflective capacity and on their construction of a holistic professional identity.

샘플

Sample

이러한 1학기 시그니처 리플렉션에 사용된 글쓰기 프롬프트는 "자신이 상상하는 의사에 대해 쓰라; 자신의 글에서 자신에 대해 무엇을 알아차렸는가?"였다 160명의 1학년 학생들 중 4명의 학생들이 본 연구에 참여하지 않기로 결정하였고 24명의 Signature Reflections는 기술적인 문제로 포트폴리오 웹사이트를 통해 접근할 수 없었다. 나머지 132명 중 97명(73%)은 '글에서 자신에 대해 무엇을 알아차렸는가'라는 안내문 2절에 구체적으로 응답했다. 구체적으로, 자신의 글을 읽음으로써 ['시간이 지남에 따라 자신의 정체성이 변화했는지(그리고 그렇다면 어떻게 변화했는지)'를 어떻게 인식했는지]에 대한 학생들의 인상을 포착하기 위해, 우리는 리뷰를 이러한 97개의 시그니처 리플렉션으로 제한했다. 이전에 Signature Reflection이 분석된 모든 학생들은 교직원들이 그들의 정체불명의 글을 읽도록 하는 것에 동의했다. 이 프로젝트에 대한 윤리적 승인은 컬럼비아 대학교의 기관 검토 위원회에 의해 승인되었다.

The writing prompt used for these first-semester Signature Reflections was, “Write about the doctor you imagine yourself becoming; what did you notice about yourself in your writing?” Of the class of 160 first-year students, 4 students opted not to participate in this research and 24 Signature Reflections were not accessible through the portfolio website because of technical issues. Of the remaining 132 students, 97 (73%) specifically responded to the second clause of the prompt, “What did you notice about yourself in your writing?” To capture students’ impressions of, specifically, how they perceived, through reading their own writing, whether their own identities had changed over time (and if so, how), we limited our review to these 97 Signature Reflections. All students whose Signature Reflection was analyzed previously agreed to let faculty read their deidentified writings. Ethical approval for this project was granted by the institutional review board of Columbia University.

분석과정

Process of analysis

분석을 시작하기 위해 17명의 FCM 멘토가 [60개의 식별되지 않은 시그니처 리플렉션 샘플]을 검토하고 그룹별로 공통 단어와 개념을 식별했다. 6명의 연구자로 구성된 소규모 그룹은 이러한 개념을 서술 의학, 성찰적 글쓰기, 전문적 정체성 형성 문헌의 맥락 안에 두었다. 이러한 일반적인 단어와 개념은 초기 코드북의 기초를 형성했으며 포트폴리오, 특히 시그니처 리플렉션이 학생들의 성찰적 역량과 전문적 정체성 구축에 어떻게 기여했는지에 대한 새로운 개념적 표현을 구성할 수 있게 했다. 그런 다음 [나머지 37개의 시그니처 리플렉션]에 대한 코드북의 코드를 지속적으로 적용하고 검토했으며, 지속적인 비교 방법을 사용하여 코드과 코드북을 반복적으로 수정했다.23 팀이 최종 코드북에 합의했을 때, 우리 중 두 명(B.K., L.F.)은 Dedoose 소프트웨어를 사용하여 97개의 Signature Reflection 문서에 코드의 수정된 버전을 적용했습니다. 6명으로 구성된 이 팀은 매주 만나 최종 코딩에 대해 논의하고 발생하는 모든 질문을 해결했습니다. 97개의 모든 시그니처 리플렉션에 코드를 적용한 후에는 코드화된 데이터를 조사하여 새로운 패턴과 두드러진 테마를 식별한 다음 포트폴리오의 기여도에 대한 새로운 이해를 바탕으로 초기 개념 표현을 수정했다.

To initiate the analysis, 17 FCM mentors reviewed a sample of 60 deidentified Signature Reflections and, as a group, identified common words and concepts. A smaller group of 6 researchers placed these concepts within the context of the narrative medicine, reflective writing, and professional identity formation literatures. These common words and concepts formed the basis of our early code book and allowed us to construct an emergent conceptual representation of how the portfolio in general, and the Signature Reflections in particular, contributed to students’ reflective capacity and professional identity construction. We then continued to apply and review codes from the code book for the remaining 37 Signature Reflections, iteratively revising the codes and code book employing the constant comparison method.23 When the team reached agreement on a final code book, two of us (B.K., L.F.) applied revised versions of the codes to all 97 Signature Reflection documents using Dedoose software (SocioCultural Research Consultants, University of California, Los Angeles, with the William T. Grant Foundation). The six-person team met weekly to continue to discuss the final coding and to address any questions that arose. Once we had applied codes to all 97 Signature Reflections, we examined the coded data to identify emergent patterns and salient themes, and then we revised our initial conceptual representation based on our emergent understanding of the contributions of the portfolio.

시그니처 리플렉션 테마

Signature Reflection Themes

학생들이 Signature Reflections에서 설명한 것처럼 P&S 포트폴리오에 대한 반복 분석을 통해 우리는 두 가지 중요한 주제를 발견했다: 인정과 투쟁. 우리는 아래에서 이러한 주요 테마와 6개의 하위 테마를 설명하고, 각각 학생의 시그니처 리플렉션의 예시적인 인용문으로 설명합니다.

Through our iterative analysis of the P&S portfolio, as described by students in their Signature Reflections, we detected two overarching themes: Recognition and Grappling. We describe these main themes and their six subthemes—and illustrate each with exemplary quotations from students’ Signature Reflections—below.

인식

Recognition

서사의학 기법은 [자신과 다른 사람들의 이야기]에 대한 세심한 주의를 촉구하기 위해 고안되었으며, 실제로 이것은 우리 학생들의 글에서 명백했다. 우리는 학생들이 [[자신의 특성]과 [환자의 관점]에 대한 높은 인식]을 설명하기 위해 "인식"을 선택했다. 인식의 두 가지 하위 주제인 [자기 인식]과 [공감]은 학생들의 시그니처 리플렉션에 자주 등장했다.

Narrative medicine techniques are designed to foster close attention to the stories of the self and of others,18 and indeed this was evident in our student writings. We chose “recognition” to describe students’ descriptions of their heightened awareness of their own attributes and of patients’ perspectives. Two subthemes of recognition—self-awareness and empathy—appeared frequently in students’ Signature Reflections.

자각.

Self-awareness.

"당신의 글에서 당신은 당신 자신에 대해 무엇을 알아차렸습니까?"라는 글을 쓰는 프롬프트가 주어졌을 때 학생들이 그들 자신의 특성이 그들의 직업적 정체성 구축에 어떻게 영향을 미칠지에 대해 종종 쓴다는 것은 놀라운 일이 아니었다. 어떤 학생들은 구체적인 성격 특성을 명명하고 그들의 성격이 어떻게 글에 표현되는지 관찰한 반면, 다른 학생들은 포트폴리오가 어떻게 그들의 자아 인식을 향상시켰는지에 대해 언급했다. 이를 설명하기 위해 한 학생은 다음과 같이 썼다:

Given the writing prompt, “What did you notice about yourself in your writing?” it was not surprising that students often wrote about how their own attributes would influence their professional identity construction. Whereas some students named specific personality traits and observed how their personality was represented in their writing, others commented on how the portfolio enhanced their awareness of self. To illustrate, one student wrote:

학기 내내, 이전의 글들을 통해 보았듯이, 나는 정말로 의사가 되고 싶은 나 자신의 감정과 동기를 이해하려고 노력했고, 내 인생에서 나를 이 지경까지 이끈 모든 삶의 경험들과 사람들에 대해 반성했다.

Throughout the semester, as I saw through my previous writings, I really tried to get in touch with my own feelings and motives for wanting to become a doctor and reflected on all the life experiences and people that have led me to this point in my life.

공감.

Empathy.

학생들은 종종 [공감적인, 초기 의대생의 자아]를 인식했고, 이러한 인식이 시그니처 리플렉션의 가치 있는 배당금이라고 보고했다. 이를 설명하기 위해 한 학생은 다음과 같이 썼다:

Students frequently recognized their empathic, early-medical-school selves and reported this awareness to be a valuable dividend of the Signature Reflection. To illustrate, one student wrote:

하지만 이번 학기 포트폴리오를 읽으며 환자들과 공감하고 적절한 관심을 줄 수 있는 능력을 잃지 않을 것이라는 희망을 갖게 되었습니다. 첫 학기 동안 저는 환자들을 위해 작은 관대한 행동을 하는 것이 매우 의미가 있다는 것을 배웠습니다.

However, reading my portfolio entries from this past semester has given me some hope that I won’t lose the ability to empathize with patients and give them proper attention. During both of my [first semester] clerkships I learned that going out of my way to perform small acts of generosity for patients can be very meaningful.

학생 시그니처 리플렉션은 [다양한 관점에 대한 인식]을 보여주고 [환자의 이야기를 전달함]으로써 공감을 표현했다. 다른 학생은 다음과 같이 말했다:

Student Signature Reflections expressed empathy by showing an awareness of multiple perspectives and by relaying patient stories. Another student commented:

의학 교육 과정에서 이러한 것들을 잊는 것은 매우 쉬울 수 있지만, 제가 쓴 글을 돌아보면…. 나는 아직도 '환자'를 [의학적 '문제']라기보다는 [사람, 독특하고 중요하고 가치 있는 이야기와 관점, 삶의 경험을 가진 개인]으로 우선시하고 있다는 사실에 안심이 된다

In the course of medical training, it can be very easy to forget these things—but looking back on my writing.… I am reassured by the fact that I still view “patients” first as people, as individuals with unique, important and worthwhile stories, perspectives, and life experiences, rather than as medical “problems.”

이 학생의 의견은 시그니처 리플렉션이 지원하는 종적 관점의 중요성과 가치를 강조했다. 이 연습에 참여하면서 학생은 "잊기가 매우 쉬울 수 있다"는 것을 깨달았다.

This student’s comment highlighted the importance and value of the longitudinal perspective supported by the Signature Reflections; in participating in this exercise, the student realized that “it can be very easy to forget.”

그래플링

Grappling

또 다른 흥미롭지만 놀랍지 않은 주제는 학생들이 시간이 지남에 따라 [변화와 불확실성에 대해 논평하는 것]과 관련이 있었다. 우리는 이전 포트폴리오 항목의 내용에서 마주친 변화나 놀라움으로 학생들의 레슬링에 대한 설명을 포착하기 위해 "드잡이Grappling"을 가장 적합한 용어로 선택했다. 그래플링은 다음의 경우에 명백했다.

- (1) 학생들이 그들 내부의 변화에 대해 토론할 때,

- (2) 감정적 거리와 연민의 균형을 맞추는 것에 대한 그들의 걱정에서,

- (3) 그들이 질문을 하거나 경이로움을 나타낼 때, 또는

- (4) 그들이 불안감을 표현했을 때.

이러한 의견은 시그니처 리플렉션을 작성하는 활동이 반사 능력을 촉진하는 메커니즘을 설명하는 것처럼 보였다.

Another intriguing, but not surprising, theme pertained to students commenting on change and uncertainty over time. We chose “grappling” as the most fitting term to capture students’ descriptions of their wrestling with changes or surprises they encountered in the content of their earlier portfolio entries. Grappling was evident

- (1) when students discussed the changes within themselves,

- (2) in their worries about balancing emotional distance with compassion,

- (3) when they asked questions or exhibited wonder, or

- (4) when they expressed anxiety.

These comments appeared to elucidate a mechanism by which the activity of writing a Signature Reflection both fostered—and was fostered by—reflective capacity.

내부 변화.

Internal change.

많은 학생들이 1학기 포트폴리오 글을 통해 [관찰한 관점의 변화]에 대해 글을 썼다. 위에서 인용한 세 학생과 같은 많은 학생들이 긍정적인 교훈을 얻었다고 생각하는 변화에 주목한 반면, 다른 학생들은 부정적인 것으로 인식하는 변화에 직면했다. 학생들은 자신감, 공감, 기술의 변화에 주목했다. 한 사람은 다음과 같이 말했다:

Many students wrote about the changes in their perspectives that they observed through their first-semester portfolio writings. Whereas many students, such as the three whose quotes appear above, noted changes that they considered positive lessons learned, others confronted changes that they perceived as negative. Students noted changes in their confidence, empathy, and skills. One commented:

지난 학기에 내가 쓴 글을 돌아보면 하나의 주제가 떠오른다. 그것은 불편하거나, 다르고, 혼란스럽거나, 불확실한 느낌을 받는 것 중 하나이다. 그것은 그 불편함, 다른 것, 혼란 또는 불확실성에서 이해를 향해 나아가기 위해 노력하는 것 중 하나이다.

Looking back over what I wrote this past semester, a theme emerges. It’s one of being okay with feeling uncomfortable, different, confused, or uncertain. It’s one of striving to move from that discomfort, otherness, confusion, or uncertainty towards an understanding.

또 다른 사람은 다음과 같이 썼다:

Another wrote:

저는 제가 쓴 글의 어둠에 호기심이 있습니다. 왜냐하면 저는 제 자신을 꽤 긍정적인 사람으로 보고 있기 때문입니다. 그리고 저는 여전히 콜롬비아 의과대학과 같은 기관에 있는 것에 대해 대단히 감사하게 생각합니다. 제 첫 작품에 담긴 [설렘과 긍정적인 전망이 이렇게 많이 사라졌다는 사실]에 놀랐다. 나는 학교를 다니고 새로운 곳에 자신을 통합하는 것은 힘든 일이고 약간 우울해지기 쉽다고 생각한다.

I’m rather intrigued about the darkness of my writing because I see myself as a fairly positive person, and I still feel immensely grateful to be at an institution like Columbia for medical school. I was surprised that the excitement and positive outlook contained in that first piece has worn off to such a large extent. I guess school and integrating yourself into a new place is a lot of hard work and it’s easy to get a little down.

실제로 위의 학생들은 'emerging theme'를 파악했을 뿐만 아니라, 이에 대한 놀라움과 불편함을 표현했다. 이러한 놀라움과 그에 따른 명백한 불편함은 이 메타 반사 연습에 의해 독특하게 촉진될 수 있다.

Indeed, the students above not only identified an “emerging theme” but also expressed surprise and discomfort in doing so. This surprise, and the evident discomfort that ensued, may be uniquely facilitated by this meta-reflection exercise.

이분법: 감정적 거리와 동정심의 균형을 맞추는 것.

Dichotomies: Balancing emotional distance and compassion.

학생들은 시그니처 리플렉션을 쓰는 것이 어떻게 그들이 갈등이나 "이분법"을 인지할 수 있게 해주는지를 표현했다. – [문화에 동화되거나 전문가가 되는 것]과 [자기를 유지하는 것] 사이, [건강한 감정적 거리를 유지하는 것]과 [동정심을 보이는 것] 사이. 한 학생은 이러한 인식을 "장벽"을 지나치는 것으로 설명했다:

Students expressed how the act of writing the Signature Reflection allowed them to perceive conflicts or “dichotomies”—between acculturating or becoming a professional and maintaining self; between maintaining a healthy emotional distance and showing compassion. One student described this awareness as seeing past “the barrier”:

하지만, 제가 쓴 글에서 장벽을 무너뜨린 순간들이 있었습니다. 그리고 [이] 나온 것은 본질적으로 불협화음인 이분법이었습니다. 내가 잠재적으로 배울 것들에 대한 흥분이지만, 내가 더 이상 관계를 맺지 못할 것들에 대한 두려움(내가 배울 것들 때문에).…

Yet, there were moments in my writings where I brought down the barrier and [what] came out was a dichotomy, dissonant in nature. Excitement about the things I would potentially learn, but fear for the things I could no longer relate to (due to the things I will learn).…

또 다른 학생은 그녀가 지식 습득에 초점을 맞춘 것과 대조적으로 그녀의 초기 이상주의를 설명했다:

Another student described her initial idealism in contrast to her focus on knowledge acquisition:

그녀를 데려온 날들을 묘사해야 했던 우리의 [첫 번째 글쓰기 과제]는 [내가 의대에 있는 최종 목표(사람들을 돕는 것)]을 [어떻게 종종 잊게 되는지] 생각하게 만들었다. 나는 하얀 코트 의식의 흥분이 내 혈관을 타고 흐르고 난 후에 그것을 썼다. 학기가 계속 진행되면서 나는 때때로 생화학 교과서의 페이지들에 대한 감정을 잊곤 한다는 것을 알아차렸다. 그것은 실제로 환자들을 돕는 것과는 거의 관련이 없는 것처럼 보였다.

Our very first writing assignment where we had to describe the days that brought us her[e] made me think about how I would often forget about the end goal of being in medical school—to help people. I wrote it after the hyper of the white coat ceremony was coursing through my veins. As the semester progressed onwards I noticed that sometimes I would forget that sentiment to the pages of biochemistry textbooks that seemed to have little connection to actually helping patients.

학생들은 그들이 [어떻게 변화하고 있는지 혹은 어떻게 변화가 불가피할 것이라고 예측하는지]를 인식하면서 [두려움과 흥분]을 모두 묘사했다. 또한, 후자의 인용문에서 제시된 바와 같이, 우리는 포트폴리오 항목을 검토하는 행위가 일상생활에 너무 깊이 짜여져 일상생활에서 감지할 수 없는 갈등과 경쟁적 요구에 대한 학생들의 인식을 뒷받침했을 수 있다고 제안한다.

Students described both fear and excitement as they recognized how they were changing or how they predicted that change would be inevitable. Furthermore, as suggested by the latter quote, we propose that the act of reviewing their portfolio entries may have supported students’ recognition of conflicts and competing demands that were so deeply woven into their daily lives as to be undetectable day-to-day.

궁금증과 의문.

Wonder and questioning.

학생들은 종종 [어려운 질문들을 조사]하고, 그들의 [과거에 대해 궁금해]하고, [미래에 자신을 투영]하기 위해 시그니처 리플렉션 연습을 사용했다. 이러한 시그니처 리플렉션은 호기심, 상상력, 그리고 시간의 앞뒤로 자신의 위치를 바꿔놓았다. 예를 들어, 한 학생은 다음과 같이 생각했습니다:

Students often used the Signature Reflection exercise to examine thorny questions, to wonder about their past selves, and to project themselves into the future. These Signature Reflections relayed curiosity, imagination, and the repositioning of self back and forth in time. For example, one student pondered:

나의 오래된 글을 되돌아보고 시간의 거리를 두고 보는 것은 정말 흥미롭다… 나는 비록 내가 더 이상 그 사람이 아니더라도 그 글을 쓴 사람을 좋아한다. 그 여자가 어떤 의사가 될 지는 잘 모르겠어요, 왜냐하면 저는 이미 그 여자에게서 어느 정도의 해리를 느끼고 있기 때문인 것 같아요. 나는 그녀가 훌륭한 의사였을 것이라고 생각한다: 약간 순진하지만, 믿을 수 없을 정도로 낙관적이다. 걱정하는. 배려하는. 희망적이다.

It’s really interesting to look back on my old writing and see it with the distance of time … I like the person who did the writing, even if I’m no longer exactly that person. I am not sure what kind of doctor that woman is going to become, I guess because I already feel a level of dissociation from her. I think she would have been a great doctor: a little naive, but incredibly optimistic. Concerned. Considerate. Hopeful.

다른 고려 사항:

Another considered:

저는 지난 학기부터 제가 쓴 글을 읽으면서 [환자로 하여금 의사들이 원하는 만큼의 정보를 공개하지 못하게 하는 의사소통의 장벽]과 다른 문제들에 특히 주의를 기울였다는 것을 깨달았습니다. 언어와 문화의 차이, 시간의 제약, 신체적, 정서적 불편함 등 말이죠. 그런데도 이 글을 쓰면서 나는 다른 의사들을 미행하거나 내가 직접 인터뷰를 진행하면서 목격한 '불완전한' 의사소통에 대한 나의 집착이 궁금해진다. 나는 또한 왜 "완벽한" 의사소통은 친밀하든 그렇지 않든 간에 항상 정보를 드러내는 것에 대한 완전한 공개와 완전한 편안함을 수반한다고 생각하는지 궁금하다.

I’ve come to recognize in reading my writing from the past semester that I’ve been particularly attentive to communication barriers and other issues that prevent patients from disclosing as much information as clinicians might hope: language and cultural differences, time constraints, and physical and emotional discomfort, among many others. And yet, as I write this, I wonder about my fixation on the “imperfect” communication I have witnessed while shadowing other doctors or conducting my own interviews. I wonder, too, why I seem to think that “perfect” communication always involves full disclosure and complete comfort with revealing information, whether intimate or not.

일부는 Signature Reflection을 ["시간의 거리를 두고" 볼 수 있는 가치 있는 특성을 기록하고 문서화하기 위한 시금석]으로 사용했습니다. 바로 위의 인용문의 저자처럼, 학생들에게, [자신을 관찰하고 트렌드를 인식하는 행위]는 그들이 가지고 있는 가정, 그들의 가치, 그들의 직업적인 목표, 그리고 심지어 의학의 실천에 대한 의문으로 이어졌다.

Some used the Signature Reflection as a touchstone to note and document valued characteristics that they were able to see “with the distance of time.” For other students, such as the author of the quotation immediately above, the act of observing themselves and recognizing trends led to questioning the assumptions they held about themselves, their values, their professional goals, and even the practice of medicine.

불안.

Anxiety.

학생들은 자신의 글에서 [불안감]을 자주 관찰했고, 의학교육의 무수한 요구로 인한 '불확실성', '가짜', '답답함' 등에 대해 언급하기도 했다. 이를 설명하기 위해 한 학생은 다음과 같이 썼다:

Students frequently observed anxiety in their own writing, often commenting on the “uncertainty,” “faking,” and “frustration” caused by the myriad demands of medical education. To illustrate, one student wrote:

이번 학기 내 글에서 반복되는 주제는 불안이었다. 나는 디즈니랜드의 문을 뛰어다니는 아이처럼 의대에 입학했다. 5개월 후, 그 흥분은 불확실성, 불안, 그리고 두 번째 추측의 홍수로 압도되었다.

A recurring theme in my writing this semester has been anxiety. I entered medical school like a kid running through the gates of Disneyland. Five months later, that excitement has been overwhelmed by a flood of uncertainty, insecurity, and second-guessing.

또 다른 의견은 다음과 같다:

Another commented:

제가 "아웃사이더가 되어라"에 대한 제 글을 읽을 때, 저는 여전히 제가 흰 코트를 입을 때마다 속이는 것처럼 얼마나 많이 느끼는지 생각해요. 내가 아는 것보다 아는 것이 더 많은 척을 하고 있다는 것. 나는 일상 생활에서 많은 경우에, "당신이 해낼 때까지 그것을 속일 수 있다"는 것을 알고 있다. 하지만 내가 의사가 되기 위한 훈련에서는, 위험이 더 큰 것 같다.

When I read my piece on “Being an outsider,” it strikes me how very much I still feel like I’m faking every time I put my white coat on. That I am pretending that I know so much more than I do. I know that in many instances in day-to-day living, one can “fake it till you make it.” But in my training to be a doctor, it seems like the stakes are higher.

하지만 한 학생이 더 관찰했습니다:

Yet one more student observed:

그러나 내가 알아차린 것은 단절이다. 나는 연결과 느낌 그리고 배려에 대해 쓰지만, 나의 일상적인 활동은 관련이 없다. 나는 매일 대부분의 시간을 의료행위를 할 수 있는 사실fact들을 연구하는데 보낸다. 물론 그것은 필요하지만, 나는 여전히 궁금하다: 우리는 정말 오랜 추적 동안 그것들을 무시함으로써 우리의 목표를 진전시키는가? 나는 시간을 생산적으로 사용하지 못하면 괴로워한다. 기차에 앉아 있는 5분도 책을 읽고, 공부하고, 의사소통하는 등 생산적이어야 한다. 하지만 인내심 있는 학생이 될 수 없는데 어떻게 인내심 있는 의사가 될 수 있을까요?

What I notice however, is a disconnect. I write about connecting and feeling and caring, but my daily activities are unrelated. I spend most of each day studying the facts that allow one to practice medicine. It is necessary of course, but I still wonder: Do we really further our goals by ignoring them during the lengthy pursuit? I get frustrated easily when I don’t use my time well. Even five minutes of sitting on a train has to be productive—reading, studying, communicating. Yet how will I be a patient doctor when I can’t be a patient student?

학생들은 자신의 성찰을 검토하면서 [직업적 목표, 가족, 친구, 개인적 행복과 같은 여러 요소와 증가하는 교육적 요구의 균형을 맞추는 것]에 대해 언급하면서 일상생활에서 얼마나 어려움을 겪고 있는지에 주목했다. 이러한 학생들에게, 시그니처 리플렉션은 이전에 그들 자신이나 그들의 멘토에 의해 주목받지 못했거나 검토되지 않은 그들 내부의 불안이나 불안에 대한 인식으로 표면화되었을 수 있다.

In reviewing their reflections, students noted the extent to which they were grappling within their everyday lives, as they commented on balancing multiple factors such as professional goals, family, friends, and personal well-being with increased educational demands. For these students, the Signature Reflection may have surfaced a recognition of a disquiet or angst within themselves that lay previously unnoticed or unexamined either by themselves or their mentors.

논의

Discussion

[주기적인 메타 성찰(Signature Reflection과 같은)로 보강된 필수적인 종단적 서사적 포트폴리오]는 학생들에게 인식과 그래플링에 형태를 부여할 수 있는 연습과 공간을 제공한다. 시간적 거리를 둔 상태에서, 학생들은 그들의 과거에 대한 반성을 할 수 있다; 그들은 그들의 성장과 변화를 감시하고 고려할 기회를 가진다. 이러한 성찰적 과정은 일부에게는 잠재적으로 불편하지만 궁극적으로 전체적인 직업적 정체성의 구축을 촉진할 수 있다. 한 학생이 이 아이디어를 잘 포착했습니다: "제가 쓴 것을 돌이켜보면… 주제가 하나 나타납니다…. 그것은 그 불편함, 타자성, 혼란, 불확실성에서 이해를 향해 나아가기 위해 노력하는 것 중 하나이다"

A required, longitudinal narrative portfolio, augmented by periodic meta-reflection (such as our Signature Reflection), offers students the practice and space to give form to recognition and grappling. With the distance of time, students are able to reflect on their past reflections; they have the opportunity to monitor and consider their growth and change. This reflective process, though potentially uncomfortable for some, may ultimately foster the construction of a holistic professional identity. One student captures the idea well: “Looking back over what I wrote …, a theme emerges.… It’s one of striving to move from that discomfort, otherness, confusion, or uncertainty towards an understanding.”

이러한 시그니처 리플렉션에서 표현된 [인식과 고심recognition and grappling]은 놀라운 일이 아닙니다. 실제로, 다른 사람들은 창의적인 글쓰기가 어떻게 [자기 인식과 공감의 발달]을 지원하는지 우아하게 묘사했다. 게다가, 불확실성과 갈등과 같은 의대생의 직업 정체성과 관련된 주제들은 1950년대 초에 르네 폭스에 의해 주목되었다. 그 이후로 교육자들은 의대생들의 정체성, 가치, 신념 통합의 중요한 조절자와 같은 주제들을 계속해서 확인해 왔다. 우리의 연구 결과는 우리의 [서사적 포트폴리오와 시그니처 리플렉션]이 학생들이 이전에 다른 연구자들이 보고한 [변화하는 정체성, 갈등 및 불확실성]에 대한 주제를 스스로 [발견하고, 해결하고, 인식할 수 있도록 함]으로써 이러한 중요한 주제를 보완하고 확장한다. 다른 사람들이 학생들의 전문적 정체성 구축 경험을 포착하기 위해 녹음된 받아쓰기와 인터뷰를 사용한 반면, 우리는 대신 학생들이 직접 만든 해석에 의존해왔다. 게다가, 우리는 우리의 메타 반사 운동이 특히 강력한 방식으로 이 과정을 촉진한다고 믿는다: 학생들이 자신의 [시그니처 리플렉션을 쓰는 것]은 [자신이 누구인지, 그리고 자신이 누구가 되고 있는지에 대한 인식]을 [표면화하고 영구적인 형태로 포착]할 수 있게 해준다. 이러한 신체적 표현은 그들의 현재와 미래의 자아, 그들의 동료와 교수진-멘토, 그리고 더 광범위한 의학 교육 공동체에 의해 검토될 수 있다. 따라서, 시그니처 리플렉션 자체는 성찰적 글쓰기에 관한 학술 문헌에 기여한다.

The recognition and grappling expressed in these Signature Reflections are not surprising. Indeed, others have elegantly described how creative writing supports the development of self-awareness and empathy.6,24–26 Furthermore, themes related to medical student professional identity, such as uncertainty and conflict, were noted by Renée Fox27 as early as the 1950s. Since that time, educators have continued to identify such themes as important modulators of medical students’ integration of their identities, values, and beliefs.10,15,28 Our findings complement and extend these important themes by suggesting that our narrative portfolio and Signature Reflection allow students to discover, grapple with, and recognize for themselves the themes of changing identity, conflict, and uncertainty that other researchers have previously reported. Whereas others have used audiotaped dictations and interviews to capture students’ experience of professional identity construction,29–31 we have relied instead on interpretations created by students themselves. Moreover, we believe that our meta-reflective exercise promotes this process in a particularly powerful way: The students’ writing of their Signature Reflection allows their perceptions of who they are and who they are becoming to surface and be captured in permanent form. This physical representation can be examined by their present and future selves, their peers and faculty–mentors, and the broader medical education community. Thus, the Signature Reflections themselves contribute to the scholarly literature on reflective writing.

P&S 포트폴리오는 다음과 같은 서술적 의학 과정을 통해 [인식과 그래플링이 일어날 수 있는 성찰 공간]을 만들었다:

- 호기심을 유발하는 서사적 텍스트의 면밀한 읽기;

- 개별 프로세스를 준수하는 프롬프트를 사용한 개방형 쓰기; 그리고

- 학생들이 그들의 직업적 정체성을 인식하고, 형태를 부여하고, 구성에 참여하는 것을 돕는 메타 성찰.

이 과정을 통해 FCM 교수진은 질문을 하고 형태를 갖추기 위해 참석함으로써 지원적이고 비판단적인 멘토링을 제공한다. 자유로운 개인 맞춤형 질문은 학생들의 반응을 촉진하고 갈등, 질문, 불확실성을 표현하고 토론할 수 있는 장을 제공한다. 우리는 서사 의학 포트폴리오 커리큘럼의 캡스톤 과제인 시그니처 리플렉션이 의대 과정에서 전개되면서 학생들이 불확실성과 씨름하도록 장려하는 모델 역할을 한다고 믿는다.

The P&S portfolio created a reflective space wherein recognition and grappling could occur through the following narrative medicine processes:

- close reading of narrative texts that encourage curiosity;

- open-ended writing using prompts that honor individual processes; and

- meta-reflection that helps students notice, give form to, and engage in the construction of their professional identity.

Throughout this process, FCM faculty provide supportive, nonjudgmental mentoring by asking questions and attending to form. The open-ended, personalized questions foster responses from students and provide a forum for expressing and discussing conflicts, questions, and uncertainties. We believe that the capstone assignment of our narrative medicine portfolio curriculum, the Signature Reflection, serves as a model to encourage students to grapple with uncertainty as it unfolds over the course of medical school.

비록 우리의 데이터 소스가 실제 학생들의 글이었지만, 인터뷰나 포커스 그룹을 통해 학생들에게 우리의 발견을 확증하도록 요청하면 신뢰성이 향상될 것이다. 또한 학생의 73%만이 시그니처 리플렉션 프롬프트에 포괄적으로 응답했다. 그 결과, 우리는 (반사 공간의 개방성을 유지하면서) 글쓰기 프롬프트와 지침을 보다 명확하게 만들었다.

Although our data source was actual student writings, asking students via interviews or focus groups to corroborate our findings would enhance trustworthiness. Also, only 73% of students responded comprehensively to the Signature Reflection prompt; as a result, we have made writing prompts and instructions more explicit (while still maintaining the openness of a reflective space).

우리의 목표는 학생들의 평생 성찰 기술을 육성하는 것이지만, 학생들의 1학기 시그니처 리플렉션에 대한 이러한 단면 분석은 학생들의 포트폴리오 참여의 장기적 결과를 평가할 수 없다. 이러한 초기 Signature Reflections로부터 배운 내용에 고무되어, 우리는 이러한 성찰적 과정을 통해 학생들이 얻는 이익이 시간이 지남에 따라 증가할 것으로 기대한다. 우리는 현재 의대 첫 3년 동안의 글쓰기 항목을 포함하도록 분석을 확장하고 있으며, 다음 분석에서는 종적 정체성 구축에 더 중점을 둘 계획이다. 앞으로 P&S 포트폴리오가 멘토링 과정과 의대생들의 공동체 의식에 미치는 영향을 연구하고자 한다.

Although our aim is to foster lifelong reflective skills in our students, this cross-sectional analysis of students’ first-semester Signature Reflections does not enable us to assess the long-term consequences of students’ participation in the portfolio. Encouraged by what we learned from these early Signature Reflections, we expect students’ benefits from this reflective process to increase over time. We are currently extending our analysis forward to include writing entries from the first three years of medical school, and we plan for our next analysis to focus more closely on longitudinal identity construction. Going forward, we hope to study the effect of the P&S Portfolio on the mentoring process and on medical students’ sense of community.

우리는 시그니처 리플렉션에 의해 구체화된 "거울" 연습이 우리 기관을 훨씬 뛰어넘는 유용성을 가지고 있다고 믿는다. 여기에 제시된 [비평가적 성찰적 글쓰기 포트폴리오]와 같은 [성찰적 공간] 내에 둔다면 때, 다른 의학 교육자들도 유사한 [메타 성찰 프로세스]를 채택하여 학생들의 [전인적 직업 정체성 구축]을 장려하고, 학생들로 하여금 [자신이 누구가 되고 있는지]에 대한 [종적 관점]을 제공할 수 있다.

We believe that the “mirror” exercise embodied by the Signature Reflection has utility well beyond our institution. When situated within a reflective space such as the nonevaluative reflective writing portfolio presented here, other medical educators can adopt a similar meta-reflection process to encourage students’ construction of a holistic professional identity and to provide them with a longitudinal perspective on who they are becoming.

Looking Back to Move Forward: First-Year Medical Students' Meta-Reflections on Their Narrative Portfolio Writings

PMID: 29261540

PMCID: PMC5976514

DOI: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000002102

Free PMC articleAbstract

The day-to-day rigors of medical education often preclude learners from gaining a longitudinal perspective on who they are becoming. Furthermore, the current focus on competencies, coupled with concerning rates of trainee burnout and a decline in empathy, have fueled the search for pedagogic tools to foster students' reflective capacity. In response, many scholars have looked to the tradition of narrative medicine to foster "reflective spaces" wherein holistic professional identity construction can be supported. This article focuses on the rationale, content, and early analysis of the reflective space created by the narrative medicine-centered portfolio at the Columbia University Vagelos College of Physicians and Surgeons. In January 2015, the authors investigated learning outcomes derived from students' "Signature Reflections," end-of-semester meta-reflections on their previous portfolio work. The authors analyzed the Signature Reflections of 97 (of 132) first-year medical students using a constant comparative process. This iterative approach allowed researchers to identify themes within students' writings and interpret the data. The authors identified two overarching interpretive themes-recognition and grappling-and six subthemes. Recognition included comments about self-awareness and empathy. Grappling encompassed the subthemes of internal change, dichotomies, wonder and questioning, and anxiety. Based on the authors' analyses, the Signature Reflection seems to provide a structured framework that encourages students' reflective capacity and the construction of holistic professional identity. Other medical educators may adopt meta-reflection, within the reflective space of a writing portfolio, to encourage students' acquisition of a longitudinal perspective on who they are becoming and how they are constructing their professional identity.

'Articles (Medical Education) > 전문직업성(Professionalism)' 카테고리의 다른 글

| "요즘 애들": 밀레니얼 학습자에 대한 우리의 대화 다시 생각하기 (Med Educ, 2019) (0) | 2023.01.13 |

|---|---|

| 세대적 상황성: 보건의료전문직에서 세대적 고정관념에 도전하기 (Med Teach, 2022) (0) | 2023.01.10 |

| 어떻게 의과대학이 공감을 바꾸는가: '환자에 대한 공감'과의 사랑 및 이별 편지 (Med Educ, 2020) (0) | 2022.10.04 |

| 초기 임상실습에서 전문직정체성형성 이해하기: 새로운 프레임워크(Acad Med, 2019) (0) | 2022.08.17 |

| 보건전문직 교육에서 공감: 무엇이 효과적이며, 격차와 개선 영역은? (Med Educ, 2022) (0) | 2022.08.10 |