주관적 평가를 측정할 때 동의-비동의 문항 사용의 재고(Res Social Adm Pharm. 2022)

Towards a reconsideration of the use of agree-disagree questions in measuring subjective evaluations

Jennifer Dykema a,b,*, Nora Cate Schaeffer a,b, Dana Garbarski c, Nadia Assad a, Steven Blixt d

서론

Introduction

태도 측정에 대한 그의 중요한 연구에서 렌시스 리커트의 공로를 인정받아, 동의-불일치(AD) 또는 리커트 질문은 태도와 의견을 평가하기 위해 가장 자주 사용되는 응답 형식 중 하나이며, 수많은 연구와 많은 국가 및 연방 조사에서 나타난다. 다음 질문에서 알 수 있듯이 [AD 질문]은 응답자에게 진술을 제공하고 동의 수준을 평가하도록 요청합니다:

- 의학 연구원들은 참가자들의 정보를 비공개로 하고 안전하게 유지하기 위해 매우 열심히 일한다. 당신은 강하게 동의하는가, 동의하는가, 동의하지 않거나 동의하지 않는가, 동의하지 않는가, 아니면 강하게 반대하는가?

Credited to Rensis Likert in his seminal research on attitude measurement, agree-disagree (AD) or Likert questions are among the most frequently used response formats to assess attitudes and opinions, appearing in numerous studies and many national and federal surveys.1, 2, 3 As illustrated by the following question, AD questions present respondents with statements and ask them to rate their level of agreement:

- Medical researchers work extremely hard to make sure they keep information from participants private and secure. Do you strongly agree, agree, neither agree nor disagree, disagree, or strongly disagree?4

연구자들이 AD 질문의 긍정적인 심리학적 특성에 대해 썼지만, 이러한 항목의 보편성은 사용의 용이성 때문일 가능성이 높다. AD 질문으로 구성된 척도는 진술의 내용이나 복잡성에 관계없이 각 진술에 대해 [동일한 응답 범주]를 사용할 수 있고, 자체 관리 설문지의 경우 연구자가 그리드에서 여러 AD 질문을 [경제적으로 포맷]할 수 있기 때문에 실질적으로 매력적이다.

While researchers have written about the positive psychometric properties of AD questions,5 the ubiquity of these items is also likely due to their ease of use. Scales comprised of AD questions are practically appealing because the same response categories can be used for each statement regardless of the content or complexity of the statements, and for self-administered questionnaires, researchers can format multiple AD questions economically in a grid.6,7

그러나 이러한 긍정적인 기능은 [응답자의 부담 증가]로 상쇄될 수 있으며, 이는 [데이터 품질을 저하]시킬 수 있으며, 설문지 설계자들이 [항목별(IS) 질문을 옹호]하도록 만들었다. [IS 질문]은 응답 차원에 맞게 조정된 응답 범주를 사용하여 질문의 기본 응답 차원에 대해 직접 질문하기 위해 작성됩니다. 예를 들어 IS 버전의 예제 질문은 열심히 일하는 강도를 평가하는 응답 범주를 사용하여 의료 연구자가 열심히 일하는 방법의 기본 응답 차원을 측정하기 위해 작성된다:

- 의학 연구자들은 참가자들의 정보를 비공개로 하고 안전하게 하기 위해 얼마나 열심히 일할까요? 전혀 열심히 하지 않음, 조금 열심히 하지 않음, 다소 열심히 함, 매우 열심히 함, 극도로 열심히 함?

These positive features, however, may be offset by increased burden for respondents, which may reduce data quality, and has led questionnaire designers to advocate for item-specific (IS) questions.6, 7, 8, 9 IS questions are written to directly ask about a question's underlying response dimension with response categories tailored to match the response dimension.6,7,9 For example, an IS version of the example question would be written to measure the underlying response dimension of how hard medical researchers work using response categories that assess the intensity of working hard:

- How hard do medical researchers work to make sure they keep information from participants private and secure: not at all hard, a little hard, somewhat hard, very hard, or extremely hard?

다음 섹션에서는 다음을 수행합니다.

- 1) AD 및 IS 질문에 대한 데이터 품질을 비교하는 실험 연구를 검토한다;

- 2) AD 및 IS 질문에 대한 응답자의 인지 처리에 관한 연구의 개념적 모델을 제시하고 검토한다;

- 3) AD 및 IS 질문 간에 자주 다르고 응답자의 인지 처리 및 데이터 품질에 영향을 미칠 수 있는 질문 특성에 대한 개요를 제공한다

- 4) AD 및 IS 질문의 사용 및 연구에 대한 최종 의견과 권고사항을 제공합니다.

In the following sections we:

- 1) review experimental studies comparing data quality for AD and IS questions;

- 2) present conceptual models of and review research concerning respondents' cognitive processing of AD and IS questions;

- 3) provide an overview of question characteristics that frequently differ between AD and IS questions and may affect respondents’ cognitive processing and data quality; and

- 4) offer concluding comments and recommendations regarding the use and study of AD and IS questions.

AD 대 IS 질문이 데이터 품질에 미치는 영향

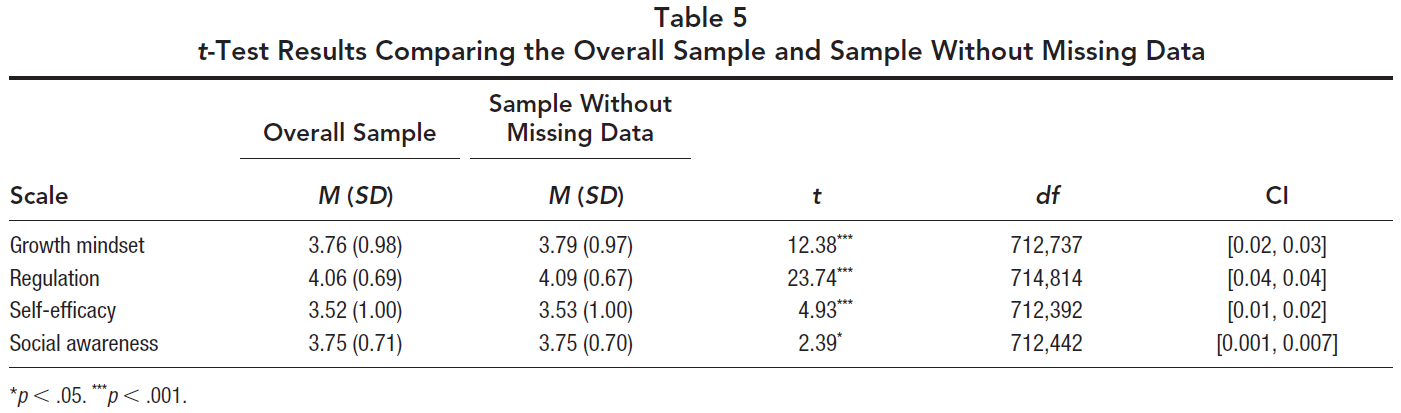

Effects of AD versus IS questions on data quality

AD와 IS 질문을 직접 비교하고 데이터 품질 또는 인지 처리 결과를 기반으로 차이를 평가하는 20개의 실험 연구를 식별했다. 여러 연구는 유효성과 신뢰성의 바람직한 데이터 품질 지표를 조사한다. 전반적으로 IS 질문이 더 높은 타당성과 신뢰성과 관련이 있다는 연구 결과가 많다. 예를 들어,

- 6개의 연구가 AD 질문과 IS 질문 사이에 일관된 차이가 없다고 보고한 반면, 3개의 연구는 IS 질문에 대해 더 높은 유효성을 보여주었고, AD 질문에 대해 더 높은 [타당성]을 보고한 연구는 없었다.

- [신뢰성]은 IS 질문에 대해 5개 연구가 더 높은 신뢰성을, AD 질문에 대해 2개 연구가 더 높은 신뢰성을 보여주었고, 2개 연구는 차이가 없다고 보고했다.

We identified 20 experimental studies that directly compare AD and IS questions and evaluate differences based on data quality or cognitive processing outcomes. Several studies examine the desirable data quality indicators of validity and reliability. Overall, a larger number of studies find IS questions are associated with higher validity and reliability. For example, while six studies reported no consistent difference between AD and IS questions,3,4,10, 11, 12, 13 three studies demonstrated validity was higher for IS questions,8,14,15 and no studies reported higher validity for AD questions. For reliability, five studies demonstrated higher reliability for IS questions,8,11,12,15,16 two for AD questions,4,13 and two studies reported no difference.3,17

연구는 또한 다음과 같은 바람직하지 않은 데이터 품질 지표를 조사했다

- 묵인 (내용에 관계없이 질문에 동의함),

- 우선순위로 인한 반응 효과 (첫 번째 범주의 체계적 선택),

- 최신성 (마지막 범주의 체계적 선택) 및

- 극단적 대응 (첫 번째 범주와 마지막 범주의 체계적 선택),

- 직선 (질문 모음의 항목에 대해 유사한 답변을 제공하는 경우),

- 항목 무응답 및

- 온라인 설문 조사에서 속도와 중단.

Studies have also examined undesirable data quality indicators including

- acquiescence (tendency to agree with a question regardless of its content),18

- response effects due to primacy (systematic selection of the first category),

- recency (systematic selection of the last category), and

- extreme responding (systematic selection of the first and last categories),

- straightlining (tendency to give similar answers to items in a battery of questions),19

- item nonresponse, and

- speeding and break-offs in online surveys.

일반적으로 더 많은 연구에서 [AD 질문]이 이러한 부정적인 결과와 관련이 있다는 것을 발견했지만, 많은 연구에서 차이를 발견하지 못했으며, 일부 연구에서는 IS 질문에 대해 더 높은 수준의 바람직하지 않은 결과를 발견했다.

- 예를 들어, 4개의 연구가 묵인을 위한 AD 질문과 IS 질문 사이의 차이가 없거나 일관성이 없다고 보고한 반면, 4개의 연구는 AD 질문이 묵인에 더 취약하다고 보고했다.

다른 반응 효과와 직선에 대한 결과는 더 다양합니다.

- 세 가지 연구는 AD 질문에 대한 우선순위, 극단적 응답 및 척도 방향 효과를 밝혀냈다;

- 한 연구는 IS 질문에 대한 최근 영향을 보고했다; 그리고 최종 연구는 AD와 IS 형식 모두에서 극단적인 반응이 있었다고 보고했다.

- 직선화의 경우, 두 연구에서 AD 척도에서 직선화가 더 많이 보고되었고, 하나는 IS 척도에서 보고되었으며, 두 연구에서는 차이가 없다고 보고되었다.

- 3개의 연구는 AD와 IS 질문에 대한 항목 누락 응답에서 일관된 패턴이 없다고 보고한 반면, 한 연구는 IS 질문에 대한 더 높은 수준을 보고했다.

- 마지막으로, 3개의 연구가 AD 형식의 질문 중에서 더 높은 수준의 속도 향상을 보고했지만, AD 또는 IS 형식은 온라인 설문 조사에서 중단 가능성에 더 큰 영향을 미치지 않았다.

In general, more studies find AD questions are associated with these negative outcomes, but a number of studies find no differences, and a few studies find higher levels of undesirable outcomes for IS questions.

- For example, while four studies reported no or inconsistent differences between AD and IS questions for acquiescence,13,16,20, 80 four studies reported AD questions were more susceptible to acquiescence.10,11,14,17

Findings for other response effects and straightlining are more mixed.

- Three studies uncovered primacy,21 extreme responding,22 and scale direction23 effects for AD questions;

- one study reported recency effects4 for IS questions; and a final study reported extreme responding was present for both AD and IS formats.2

- For straightlining, two studies reported more straightlining in AD scales,10,12 one in IS scales,22 and two studies reported no differences.21,23

- While three studies reported no consistent pattern in item-missing responses for AD and IS questions,16,21,22 one study reported higher levels for IS questions.4

- Finally, while three studies reported higher levels of speeding among questions with AD formats,21, 22, 23 neither an AD or IS format was more likely to affect the likelihood of break-offs in online surveys.22,23

AD 및 IS 질문의 인지 처리

Cognitive processing of AD and IS questions

설문지 설계자들은 AD 질문이 IS 질문보다 인지적으로 부담이 크기 때문에 데이터 품질을 낮출 가능성이 높다고 주장한다. [AD 질문의 복잡성]에 기여하는 한 가지 특징은 [질문의 "제공된" 응답 차원]과 ["기본적인" 응답 차원] 사이의 [불일치]를 응답자에게 자주 제시한다는 것이다. 응답 차원은 질문이 응답자에게 답변을 구성할 때 고려하도록 요청하는 연속체입니다. 평가 척도를 사용한 평가 및 판단에 대한 질문의 경우, 응답 차원은 다음을 설정할 수 있다

- 원자가(대상 물체의 평가가 긍정적이든 부정적이든, 예를 들어 "찬성 또는 동의하지 않음"),

- 강도(예: "전혀… 극단적이지 않다"),

- 수량(예: "대단히 … 많은 양"), 또는

- 대상 개체의 상대 빈도(예: "never … always").

Questionnaire designers argue that AD questions are more likely to lower data quality because they are more cognitively burdensome than IS questions.6, 7, 8,24 A characteristic that contributes to the complexity of AD questions is that they often present respondents with a mismatch between the question's “offered” and “underlying” response dimensions. A response dimension is the continuum a question asks the respondent to consider when constructing their answer.6,9,25 For questions about evaluations and judgments using rating scales, response dimensions can establish

- valence (whether the evaluation of a target object is positive or negative; e.g., “agree or disagree”),

- intensity (degree to which the evaluation is held; e.g., “not at all … extremely”),

- quantity (amount of the evaluation held; e.g., “none … a great deal”), or

- relative frequency of the target object (e.g., “never … always”).

표 1.4의 AD 질문을 고려합니다. 반응 범주가 제시하는 반응 차원은 [일치의 강도]입니다. 이는 진술서에 제시된 [열심히 일하는 강도]의 [근본적인 반응 차원]과 상충된다. 이러한 불일치는 응답자들이 진술에 대한 [자연적으로 발생하는 반응]을 [AD 반응 범주]에 "매핑"하기 위해 복잡한 인지 처리 단계를 수행하도록 강요한다.

Consider the AD question in Table 1.4 The offered response dimension presented by the response categories is the intensity of agreement. This conflicts with the underlying response dimension of the intensity of working hard presented in the statement. These mismatches force respondents to undertake complicated cognitive processing steps in order to “map” their naturally occurring responses to the statement onto the AD response categories.

Tourangeau 등은 응답자가 설문조사 질문에 대한 답변을 구성하는 4단계를 설명한다:

- 이해,

- 기억에서 관련 정보 검색,

- 판단을 위한 검색된 정보 사용,

- 답변 선택 및 보고.

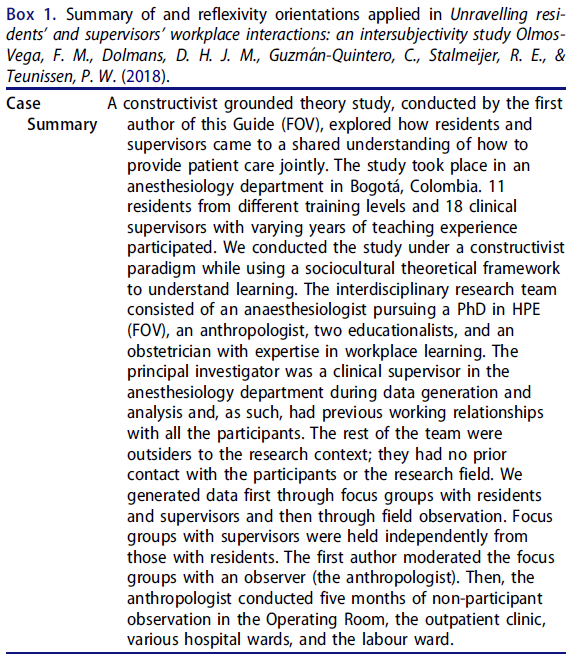

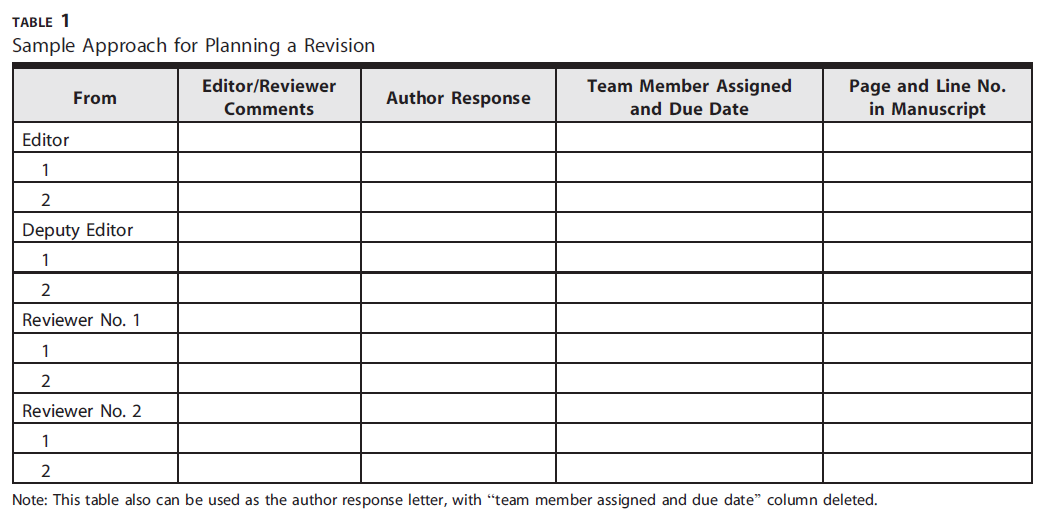

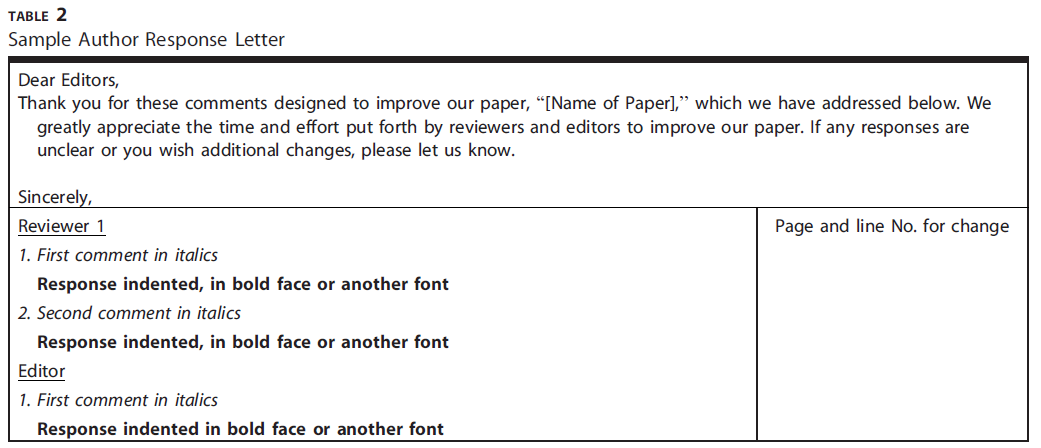

다른 것들은 이 모델을 확장하여 AD 질문에 응답하는 데 관련된 인지 단계를 추가했으며, 표 1에서 AD 및 IS 질문에 대답하기 위해 수행되는 인지 처리 단계의 개념적 모델을 제시한다.

Tourangeau et al.26 describe four stages through which respondents construct answers to survey questions:

- comprehension,

- retrieval of relevant information from memory,

- use of retrieved information to make judgments, and

- selection and reporting of an answer.

Others have expanded on this model, adding cognitive steps involved in responding to AD questions specifically,6,8,23,27,28 and in Table 1, we present conceptual models of the cognitive processing steps undertaken to answer AD and IS questions.

AD 질문에 대한 인지 처리 단계의 개념 모델

Conceptual model of cognitive processing steps for AD questions

첫 번째 단계는 응답자가 이해해야 하는 [이해]입니다

- 성명서의 문자 그대로의 의미(예: "의료 연구자들은 참가자들의 정보를 비공개로 하고 안전하게 유지하기 위해 매우 열심히 노력한다")

- 구성 요소(예: "의료 연구원", "열심히 일한다[열심히 한다] 등).

The first step is Comprehension in which the respondent must comprehend

- the literal meaning of the statement (e.g., “Medical researchers work extremely hard to make sure they keep information from participants private and secure”) as well as

- its component parts (e.g., “medical researchers,” “work [extremely] hard,” etc.).

다음으로, 식별하는 동안, 응답자는 질문의 [기본적인 응답 차원을 식별]합니다. 이는 문장의 의미를 이해하고 임계값 단어(포함된 경우)에 주의를 기울임으로써 달성됩니다. [임계값 단어]는 척도 옵션의 전체 범위를 제시하지 않고 기본 응답 차원에서 임계값을 설정하는 AD 문에 종종 포함되는 인텐시파이어(예: "매우"), 정량자(예: "가장") 또는 빈도 마커(예: "거의")입니다.

- 예를 들어, AD 질문에는 "극도로"라는 [임계값 단어]가 포함되는데, 이는 "열심히 일한다"를 수정함으로써, 근본적인 응답 차원으로서 열심히 일하는 강도를 강화하는 역할을 한다.

Next, during Identification, the respondent identifies the question's underlying response dimension, which is accomplished by understanding the meaning of the statement as well as attending to threshold words, if included. Threshold words are intensifiers (e.g., “very”), quantifiers (e.g., “most”), or frequency markers (e.g., “rarely”) often included in AD statements that establish a threshold on the underlying response dimension without presenting the full range of scale options.

- For example, the AD question includes the threshold word “extremely,” which, by modifying “work hard,” serves to reinforce the intensity of working hard as the underlying response dimension.

기본 반응 차원을 식별한 후, 응답자는 차원(생성)에 대해 자신의 내부 값(반응)을 생성해야 합니다.

- 현재 질문의 경우, 응답자는 "상당히 열심히"에 관한 내부 값을 생성합니다.

After identifying the underlying response dimension, the respondent must generate their own internal value (response) on the dimension (Generation).

- For the current question, the respondent generates an internal value of “pretty hard.”

이어지는 단계는 일련의 복잡한 인지 과정을 포함한다,

- 응답자가 자신의 내부 값인 "상당히 열심히"과 임계값인 "극단적으로 열심히" 사이의 거리를 평가한다(임계값 평가).

- 그런 다음 내부 값과 임계값 사이의 거리가 "동의", "동의하지 않음" 또는 "중립성"을 나타내는지 확인합니다(극성 평가).

Ensuing steps encompass a set of complicated cognitive processes in which the respondent

- evaluates the distance between their internal value of “pretty hard” and the threshold value of “extremely hard” (Threshold evaluation), and

- then determines whether the distance between their internal value and the threshold value indicates “agreement,” “disagreement,” or “neutrality” (Polarity evaluation).

마지막으로, [극성에 대한 평가]에 따라, 응답자는 [제안된 범주 중 하나(매핑)를 사용]하여 제안된 응답 차원에 내부 가치를 매핑해야 합니다.

- 예를 들어, 응답자는 자신의 내부 값 "매우 엄격"이 임계값 "극히 엄격"에 가깝기 때문에 "동의하지 않음"을 선택하거나, "매우 엄격"이 "극히 엄격"보다 덜 심각하기 때문에 "동의하지 않음"을 선택할 수 있다

Finally, guided by their evaluation of polarity, the respondent must map their internal value onto the offered response dimension using one of the offered categories (Mapping).

- For example, the respondent might select “agree” because their internal value “pretty hard” is close to the threshold value “extremely hard,” or the respondent could select “disagree” because “pretty hard” is less intense than “extremely hard.”

IS 질문에 대한 인지 처리 단계의 개념 모델

Conceptual model of cognitive processing steps for IS questions

비교 가능한 IS 질문에 답하기 위해 수행되는 인지 처리 단계는 단순화되고 부담이 적을 것으로 예측된다.

- 첫째, 응답자는 질문의 문자 그대로의 의미와 그 구성요소(Comprehension)를 이해해야 합니다.

- 식별 단계에서, 응답자는 질문 방식과 응답 범주의 레이블링 및 순서(예: "전혀 딱딱하지 않음", "약간 딱딱함" 등)에 의해 강화되는 기본 응답 차원을 결정합니다.

- 다음으로, 응답자는 "상당히 어려운" 내부 값을 생성한다(생성). 그러나 이 값의 배치는 제공된 범주 중 하나(매핑)에 매핑하여 직접 수행되므로 임계값 및 극성 평가를 우회할 수 있습니다.

- 현재 질문의 경우, 응답자는 부사어와 인텐시파이어의 스케일을 조정하는 연구를 바탕으로 "상당히"가 "다소"와 "매우" 사이에 있기 때문에 "다소" 또는 "매우 어렵다"를 선택할 수 있다.

The cognitive processing steps undertaken to answer a comparable IS question are simplified and predicted to be less burdensome.

- First, the respondent must comprehend the literal meaning of the question and its component parts (Comprehension).

- During Identification, the respondent determines the underlying response dimension, which is reinforced by the manner of questioning and the labeling and ordering of the response categories (e.g., “not at all hard,” “a little hard,” etc.).

- Next, the respondent generates an internal value of “pretty hard” (Generation), but placement of this value is done directly by mapping it to one of the offered categories (Mapping), thereby circumventing Threshold and Polarity evaluation.

- For the current question, the respondent could select “somewhat hard” or “very hard” because “pretty” lies between “somewhat” and “very” based on studies that scale adverbial phrases and intensifiers.29,30

AD 및 IS 질문을 단독으로 배터리로 처리할 때 응답자의 인지 노력

Respondents’ cognitive effort when processing AD and IS questions alone and in batteries

응답자의 인지적 노력 처리 AD 및 IS 질문을 조사한 연구는 질문이 단독으로 나타나는지 또는 배터리의 일부로 나타나는지, 그리고 IS 응답 범주가 질문에 따라 달라지는 정도라는 두 가지 질문 특성을 중간 정도의 노력으로 나타낸다. 표 1의 모델은 단독으로 제시된 단일 AD 질문이 더 높은 수준의 인지 처리를 필요로 할 것으로 예상하지만, 대부분의 AD 질문은 진술이 다양하지만 응답 범주가 일정하게 유지되는 배터리에서 나타난다. 이 프레젠테이션을 통해 응답자들은 질문과 범주의 패턴을 기억할 수 있으며, 생각이 덜한 답변 과정을 장려할 수 있다. 대조적으로, 여러 IS 질문이 함께 그룹화될 때, 응답자들이 가변 응답 범주를 처리하기 위해 더 많은 노력을 기울이는 것을 요구하기 때문에, 그들은 (자주, 그러나 항상 그렇지는 않다) 서로 다른 응답 차원과 응답 범주를 사용한다.

Studies examining respondents’ cognitive effort processing AD and IS questions indicate two question characteristics moderate effort: whether questions appear alone or as part of a battery; and the extent to which IS response categories vary across questions.23,28,31 While the model in Table 1 anticipates that a single AD question presented in isolation will require a higher level of cognitive processing, most AD questions appear in batteries in which the statements vary but the response categories remain constant. This presentation allows respondents to memorize the pattern of questioning and categories and may encourage a less thoughtful process of answering.32 By contrast, when multiple IS questions are grouped together, they (often, but not always) use different response dimensions and response categories, requiring respondents exert more effort to process the variable response categories.23

[응답자가 질문을 처리하고 답변하는 데 걸리는 시간의 변화]를 조사하는 연구는 이러한 제안을 크게 뒷받침한다. 응답 지연 시간(RL)은 면접관의 질문 읽기가 끝날 때부터 응답자의 답변까지 걸리는 시간을 측정합니다. 연구자들은 신뢰와 정치적 유효성에 대한 질문에 대해 RLs의 시간을 측정했는데, 이 질문의 범주는 IS 항목에 따라 다르지만 AD 항목에 대해서는 변함이 없었다. 두 연구 모두에서, 배터리의 [첫 번째 질문]에 대한 RL은 AD 항목에 대해 상당히(또는 약간 그렇게) 길었고, AD 응답 형식이 인지적으로 더 부담스러운 응답 작업을 부과했다는 일부 증거를 제공했다. 그룹으로 평가된 RLs는 신뢰에 대한 IS 질문에 대해 더 길었지만 정치적 효과는 아니었다.

Research examining variation in the time respondents spend processing and answering questions largely support these propositions. Response latencies (RLs) measure time spanning the end of an interviewer's question reading to the respondent's answer.33 Researchers timed RLs for questions about trust4 and political efficacy11 in which categories varied across IS items, but were invariant across AD items. In both studies, RLs for the first question in the battery were significantly (or marginally so) longer for the AD item, providing some evidence that AD response formats imposed a more cognitively burdensome response task. Evaluated as a group, RLs were longer for the IS questions about trust, but not political efficacy.

연구자들은 또한 AD 항목에 대해서는 응답 범주가 동일하지만 IS 항목에 대해서는 다양한 독립형 항목으로 제시된 질문에 대한 응답 시간(RT; 읽기 및 답변에 소요된 총 시간)을 조사했다. 조사결과는 카테고리의 수나 순서, PC나 스마트폰에서 질문에 대한 답변 여부와 관계없이 IS 질문의 경우 RT가 더 긴 것으로 나타났다. 대조적으로, AD 및 IS 질문 모두에 대해 응답 범주가 일정하게 유지된 그리드에서 제시된 AD 및 IS 질문에 대한 RT의 차이는 없었다.23 RT에 대한 연구를 종합하면, IS 범주의 changing nature는 응답자들이 지출하는 인지 노력의 양을 증가시킬 수 있다는 것을 보여준다.

Researchers have also examined response times (RTs; total time spent reading and answering) for questions presented as stand-alone items in which response categories were the same for AD items but varied for IS items.21, 22, 23 Findings indicated RTs were longer for IS questions, regardless of the number or ordering of categories or whether the questions were answered on PCs or smartphones. By contrast, there were no differences in RTs for AD and IS questions presented in grids in which the response categories were held constant for both the AD and IS questions.23 Taken together, studies of RTs indicate the changing nature of IS categories may increase the amount of cognitive effort respondents expend.

다른 방법론은 [그룹화된 IS 질문]의 [다양한 응답 범주]가 [더 많은 인지 노력을 필요]로 하는 반면, [그룹화된 AD 질문]의 [반복적인 질문 패턴]은 [더 피상적인 처리]를 장려한다는 증거를 제공한다. 인터뷰어가 관리하는 연구에서, 연구자들은 IS 응답 범주가 참가자들이 기억하기 어려웠기 때문에 IS 질문이 응답 난이도의 더 높은 수준의 행동 지표와 연관되어 있다고 보고했다. 질문(쇼카드 없이 11개 질문)과 항목의 음성 프레젠테이션. 연구자들은 눈 추적 기술을 사용하여 AD 항목의 경우 동일하지만 IS 질문의 경우 다양한 질문 줄기 대 응답 범주에 대해 응답자의 눈 움직임을 별도로 기록함으로써 인지 노력을 조사했다. 조사 결과는 질문 줄기에 대한 눈의 움직임에 차이가 없는 것으로 나타났지만, 응답자들은 IS 응답 범주를 더 집중적으로 처리하였으며, 더 많은 시간 동안 더 많이 보았다.

Other methodologies also provide evidence that the varying response categories of grouped IS questions require more cognitive effort while the repeated questioning pattern of grouped AD questions encourage more superficial processing. In an interviewer-administered study, researchers4 reported that IS questions were associated with higher levels of behavioral indicators of response difficulty (e.g., higher levels of uncodable answers and answers with qualifications) because the IS response categories were harder for participants to remember, an issue exacerbated by the number of questions (11 questions were asked without show cards) and aural presentation of items. Using eye-tracking technology, researchers28,34 examined cognitive effort by recording respondents’ eye movements separately for question stems versus response categories, which were the same for the AD items, but varied for the IS questions. While findings indicated no differences in eye movements for the question stems, respondents processed IS response categories more intensively, viewing them more and for longer times.

응답자의 AD 및 IS 질문에 대한 인지 노력을 조사한 연구 결과는 IS 질문에 대한 노력을 증가시키는 요인을 이해하기 위해 더 많은 연구가 필요하며, 가장 중요한 것은 그 노력이 데이터 품질과 관련이 있는지 여부이다. 응답 시간만으로는 해석하기 어려울 수 있습니다: "[응답이 지연delay된다는 것]은 질문을 처리하기 어렵거나(일반적으로 나쁜 신호), 질문이 사려 깊은 응답을 장려한다는 것을 의미할 수 있습니다(일반적으로 좋은 신호)(p. 297)." 더 긴 시간은 덜 정확한 답과 관련이 있지만, 자기 관리 기구를 사용한 실험 연구는 [시간과 정확도 사이의 관계]가 [더 길거나 더 짧은 시간일 때 덜 정확]한 곡선관계 일 수 있음을 시사했다.

Results from studies examining respondents’ cognitive effort answering AD and IS questions suggest more research is needed to understand factors that lead to increased effort for IS questions and most importantly, whether that effort is associated with data quality. Response times alone can be difficult to interpret: “delays in responding could mean that a question is difficult to process (usually a bad sign) or that the question encourages thoughtful responding (typically a good sign) (p. 297).”7 While longer times have been associated with less accurate answers,35 an experimental study with a self-administered instrument suggested the relationship between time and accuracy may be curvilinear with longer and shorter times being less accurate.36

AD 및 IS 질문 간에 다른 질문 특성 개요

Overview of question characteristics that differ between AD and IS questions

실험에서 평가되는 AD-IS 질문 쌍은 종종 인지 처리 및 데이터 품질에 영향을 미칠 수 있는 여러 질문 특성에 따라 다르다. 예를 들어, 제공된 응답 차원(AD 질문에 대한 강도 및 IS 질문에 대한 빈도)과 응답 범주의 방향([높은 것부터 낮은 것]까지 일치 대 [낮은 것부터 높은 것]까지)은 다음 AD-IS 쌍에 따라 다릅니다:

- "의사들은 환자들로부터 모든 진실을 숨기는 경우가 거의 없다: 강하게 동의하고 강하게 반대한다." 그리고

- "의사들은 환자들로부터 모든 진실을 지킨다: 절대로… 항상."

In experiments, the AD-IS question pairs being evaluated often vary on multiple question characteristics that can affect cognitive processing and data quality. For example, both the offered response dimension (intensity for the AD question and frequency for the IS question) and direction of the response categories (high to low agreement versus low to high frequency) vary for following AD-IS pair:

- “Doctors rarely keep the whole truth from their patients: agree strongly … disagree strongly” and

- “Doctors keep the whole truth from their patients: never … always.”8

응답 차원과 같은 일부 특성은 실험적으로 제어되지 않는 방식으로 AD와 IS 질문을 비교하는 연구에서 종종 공변화되어 특성의 고유하거나 조절하는 효과를 분리하는 것이 불가능하다. 반응 범주에 대한 언어 레이블의 수와 사용과 같은 다른 특성은 일반적으로 AD-IS 실험 내에서 일정하게 유지되지만, 이러한 특성은 연구에 따라 달라 결과를 일반화하는 작업을 복잡하게 만든다. AD-IS 실험에 포함된 질문을 컴파일하고 AD-IS 질문 쌍 간에 다른 주요 특성을 식별하기 위해 특징을 체계적으로 코딩했다(표 2에 요약). 우리는 이러한 특성이 AD-IS 실험 내에서 그리고 AD-IS 실험 전반에 걸쳐 어떻게 변화하는지 설명하고, 선택된 특성의 경우 데이터 품질과 관련된 결과를 간략하게 요약한다.

Some characteristics, such as response dimensions, often co-vary in studies comparing AD and IS questions in ways that are not controlled experimentally, making it impossible to isolate unique or moderating effects of the characteristics. Other characteristics, such as the number and use of verbal labels for response categories, are usually held constant within an AD-IS experiment; but these features vary across studies, complicating the task of generalizing findings. We compiled questions included in AD-IS experiments and systematically coded their features to identify key characteristics that differ between AD-IS question pairs (summarized in Table 2). We describe how these characteristics vary within and across AD-IS experiments, and for select characteristics, we briefly summarize findings regarding data quality.9,25

질문 방식

Manner of questioning

평가할 내용이 포함된 문장이 [문장]이나 [질문]으로 구성되어 있는지 여부를 묻는 방식은 AD와 IS 항목을 구별하는 것의 본질에 기본적이며 AD-IS 비교에 따라 항상 다르다. 연구자들은 AD 항목의 간접 질문 구조를 회피하는 이유로 꼽고 있으며, 6과 실험 연구의 결과는 이러한 권고를 뒷받침한다. 시선 추적 연구의 피험자들은 AD 및 IS 질문 줄기를 처리하는 동등한 인지 노력을 발휘하는 것으로 나타났지만, 실험실 환경의 피험자들은 질문에 대한 주장으로 작성되었을 때 항목의 내용을 덜 깊이 처리했다.

Questioning manner – whether the sentence with the content to be evaluated is structured as a statement or question -- is fundamental to the nature of what distinguishes AD and IS items and always differs across AD-IS comparisons. Researchers cite the indirect question structure of AD items as a reason to avoid them,6 and findings from experimental studies support these recommendations. While subjects in eye-tracking studies appeared to exert equivalent cognitive effort processing AD and IS question stems,28,34 subjects in a laboratory setting processed the content of items less deeply when they were written as assertions versus interrogatives.37

묵인

Acquiescence

연구에 따르면 제안된 응답 차원의 합의는 특히 낮은 수준의 교육을 받은 응답자들 사이에서 AD 질문이 묵인에 더 취약할 수 있는 반면, IS 응답 차원은 이를 훨씬 덜 우려하게 한다. AD 질문에 대한 묵인은 아마도 공손함, 존경심 또는 대화 관행 때문에 [반대할 이유가 없는 한 "동의"할 수 있는 사전 성향]을 가지고 있기 때문에 발생할 수 있다. AD 진술이 복잡하거나 반복적이거나 응답자에게 두드러지지 않는 항목의 대규모 그룹의 일부인 경우 그러한 경향은 악화될 수 있다. 또한, 응답 차원의 "동의" 또는 긍정적인 보기가 [일반적으로 먼저 제공]되며, 더 많은 처리를 받거나 더 호의적으로 인식될 수 있으므로 선택될 가능성이 더 높다.

Research indicates the offered response dimension of agreement may cause AD questions to be more vulnerable to acquiescence, particularly among respondents with lower levels of education,18,38,39 whereas IS response dimensions make this much less of a concern. Acquiescence for AD questions could arise because listeners have a pre-disposition to “agree” unless they have a reason to disagree, perhaps due to politeness, deference, or because of conversational practices.18,40 Such tendencies might be exacerbated if AD statements are complex or part of a large group of items that are repetitious or not salient to the respondent. In addition, the “agree” or positive end of the response dimension is usually offered first,18 and may receive more processing or be perceived more favorably, and thus more likely to be selected.31

임계값 단어

Threshold words

일반적으로 [임의적인 임계값 단어의 선택]은 내부 값을 AD 응답 범주에 매핑하려는 응답자의 노력을 복잡하게 만들 수 있으며, 궁극적으로 [단조로운 동등성의 원칙]을 위반하는 답변으로 이어질 수 있다. 문항이 [단조로운 동등성]을 갖는다는 것은 [측정되는 구조의 [기본 척도]에서 [답변에 대한 값]을 증가(또는 감소)하는 것과 상관관계가 있는 경우]이다.

Threshold words, the selection of which is typically arbitrary,8 may complicate respondents' efforts to map internal values onto AD response categories, and ultimately lead to answers that violate the principle of monotonic equivalence.7 An item possesses monotonic equivalence when increasing (or decreasing) values for the answers correlate with increasing (or decreasing) values on the underlying scale of the construct being measured.

예를 들어, 환자의 약물 비부착 non-adherence사유를 측정하기 위해 설계된 "비부착성non-adherence은 대부분 사람들의 부주의로 인한 것"이라는 문구를 고려한다. 진술이 암시하는 근본적인 반응 차원은 [부주의로 인한 비고착성이 얼마나 큰가]하는 것이다.

- 한 응답자는 불응성이 부주의로 인해 "전혀" 발생하지 않는다고 생각하기 때문에 "반대"라고 대답할 수 있고,

- 다른 응답자는 불응성이 부주의로 인해 "매우" 발생한다고 느끼기 때문에 "반대"라고 대답할 수 있습니

For example, consider the statement “non-adherence is mostly due to people being careless,” designed to measure patients' reasons for medication non-adherence.41 The underlying response dimension implied by the statement is how much non-adherence is due to carelessness.

- However, one respondent could answer “disagree” because they believe non-adherence is “not at all” due to carelessness

- while another could “disagree” because they feel non-adherence is due to carelessness “a great deal.”

두 응답자 모두 "동의하지 않음"의 값을 보고하지만, 첫 번째 응답자의 "전혀 그렇지 않음"의 내부 값은 "매우 그러함"보다 근본적인 반응 차원에서 훨씬 더 낮다. 이 항목의 [IS 버전]은 이 질문을 하는 직접적인 방법을 제공하며 응답자들이 응답 연속체에서 자신을 정확하게 주문하도록 보다 쉽게 보장한다:

- "사람들의 부주의로 인한 비고착성은 어느 정도인가요? 전혀, 조금, 다소, 꽤 많은 것인가요?"

While both respondents report a value of “disagree,” the first respondent's internal value of “not at all” is clearly much lower on the underlying response dimension than “a great deal.” An IS version of this item provides a direct method of asking this question and more readily ensures that respondents order themselves accurately on the response continuum:

- “How much is non-adherence due to people being careless: not at all, a little, somewhat, quite a bit, or a great deal?”

측정에는 [단조로운 동등성]이 필요하기 때문에, [AD 질문에 대한 반응]이 [반응 연속체의 양쪽 끝에 있는 임계값을 포함하는 경우]에만 해석할 수 있다고 주장하는 사람도 있습니다. 빈도와 같은 일부 응답 차원의 경우 극단값은 명백할 수 있다(예: "절대" 또는 "항상"). "얼마나how much"를 사용하는 양과 같은 다른 반응 차원의 경우 극단적인 양의 값이 무엇인지는 절대적으로 명확하지 않습니다. "great deal"은 "얼마나" 척도에서 가장 높은 긍정적 가치인가요? 또한, 문헌은 임계값을 전혀 포함하지 않는 AD 질문을 사용하는 도구의 예로 가득 차 있어 응답자들이 자신의 해석을 중첩할 수 있다.

Because measurement requires monotonic equivalence, some argue that responses to AD questions are only interpretable if they include threshold values at either end of the response continuum.42 For some response dimensions, such as frequency, extreme values may be obvious (e.g., “never” or “always”). For other response dimensions, such as quantity using “how much,” it is not absolutely clear what the extreme positive value should be. Is “a great deal” the highest positive value on a “how much” scale? Further, the literature is replete with examples of instruments using AD questions that fail to include a threshold value at all, allowing respondents to superimpose their own interpretations.

극성

Polarity

[AD 항목]은 거의 항상 쌍극이며, 반응 차원의 극 또는 끝을 모두 나타낸다(예: "강력히 동의한다…강력히 동의하지 않는다"). [IS 항목]은 양극성(예: "극도로 만족하지 않고 극도로 만족한다")일 수 있지만, [일반적으로 단극성](예: "전혀 만족하지 않고…극도로 만족하지 않는다" 또는 "전혀 만족하지 않고…극도로 만족하지 않는다")이다.

AD items are almost always bipolar and present both poles or ends of the response dimension (e.g., “agree strongly … disagree strongly”). While IS items can be bipolar (e.g., “extremely dissatisfied … extremely satisfied”), they are usually unipolar, presenting only one possible pole (e.g., “not at all satisfied … extremely satisfied” or “not at all satisfied … extremely dissatisfied”).

AD 질문의 기본 응답 차원이 [수량] 또는 [빈도]일 때, 해당 IS 질문은 [항상 단극]입니다. 왜냐하면 [수량]에는 "없음" 또는 "전혀 없음"보다 작은 값이 포함되지 않으며, [빈도]에는 "없음"보다 낮은 값이 포함되지 않기 때문입니다. 오직 [강도 반응 차원]만이 양극성일 수 있고, 음의 극값(예: "중요하지 않음")이 양의 극값과 동일한지 여부가 불분명한 일부 차원(예: "중요하지 않음")이 있다.

Whenever the underlying response dimension for an AD question is quantity or frequency, the corresponding IS question will always be unipolar because quantities do not contain values less than “none” or “not at all” and frequencies do not possess values lower than “never.” Only intensity response dimensions can be bipolar and there are some dimensions (e.g., “important”) where it is unclear whether the negative polar-value (e.g., “unimportant”) is equivalent to the positive polar-value.

AD 문항이 다수 포함된 GSS(General Social Survey) 항목에 대한 측정 오차 분석에서, 단극 문항이 양극 문항보다 신뢰도가 높은 것으로 나타났다. 극성의 차이만으로도 한계 분포의 차이가 발생할 가능성이 높아 항목 간의 최대 상관관계가 제한됩니다. IS 항목은 일부에서 권장하는 대로 다양한 긍정 및 부정 응답 차원을 사용할 수 있는 가능성을 제공하며, 항목은 AD 항목보다 상관 관계가 있는 방법 분산이 낮을 수 있습니다. [양극성 AD 항목]과 비교하여, [단극성 IS 항목]은 또한 응답 차원의 특정 측면에서 [더 많은 차별화 점을 제공]하고 [척도 점수의 변동을 증가]시킬 수 있습니다.

In an analysis of measurement error for items from the General Social Survey (GSS), which included a number of AD questions, results indicated unipolar questions were more reliable than bipolar questions.43 Differences in polarity alone are also likely to generate differences in the marginal distributions,44 which limit the maximum correlations among the items. IS items offer the possibility of using a variety of positive and negative response dimensions as recommended by some;45,46 and the items may have lower correlated method variance than AD items. Compared to bipolar AD items, unipolar IS items also offer more points of differentiation on a particular side of the response dimension and may increase variation for scale scores.12

반응 범주

Response categories

반응 범주는 숫자, 레이블링 및 방향에 따라 다릅니다. 연구 내 범주의 수와 레이블링은 AD-IS 쌍 간에 거의 항상 일정하게 유지되지만, 이러한 특성은 연구에 따라 상당히 다르다. 대조적으로, 범주의 값이 증가하든 감소하든 범주의 방향은 때때로 동일한 연구에서 AD-IS 쌍에 따라 달라집니다. AD-IS 실험에서 [AD 질문]에 대한 범주는 더 자주 [가치value가 감소]하는 반면(예: "동의 … 동의하지 않음"), [IS 질문]에 대한 범주는 더 자주 [증가]한다(예: "절대 … 항상"). 일부 연구에 따르면 AD 및 IS 항목의 데이터 품질은 다섯 가지 범주를 사용하여 최적화되고 단어로 완전히 레이블이 지정되며 순서가 증가할 수 있습니다. 다른 연구에서, 응답자들은 ["강력히 동의하지 않는다"와 "동의하지 않는다"를 구별하는 데 어려움]을 겪었다 "강력하게"는 잠재적으로 응답자의 [평가의 극단성]과 [확실성]을 혼동하기 때문에 수식어로서 문제가 될 수 있다.

Response categories differ in terms of their number, labeling, and direction. While the number and labeling of categories within a study is almost always held constant between AD-IS pairs, these characteristics vary considerably across studies. By contrast, category direction – whether the categories increase or decrease in value – sometimes varies across AD-IS pairs in the same study. In AD-IS experiments, categories for AD questions more often decrease in value (e.g., “agree … disagree”), while categories for IS questions more often increase (e.g., “never … always”). Some research indicates data quality for both AD and IS items may be optimized using five categories, fully labeled with words, and presented in increasing order.9,22,47 In other research, respondents had difficulty distinguishing between “strongly disagree” and “disagree.”17 “Strongly” may be problematic as a modifier because it potentially conflates the extremity of a respondent's evaluation with their certainty.48

중간 범주

Middle category

단극 IS 항목과 대조적으로, [AD 질문]은 종종 명확한 개념적 중간 범주(예: "동의하지도 동의하지도 않는다")를 포함한다. 양극성 질문에 대한 중간 범주를 포함하기 위해 데이터 품질을 평가하는 실험은 엇갈린 결과를 얻었지만, 연구에 따르면 응답자들은 원하지 않는 방식으로 AD 질문에 대답할 때 중간 범주를 사용한다. 예를 들어, 조사했을 때, 응답자들은 그 문제에 대한 [의견이 없기 때문에 중간 범주를 선택]하는 것을 압도적으로 보고했다. 연구에 따르면 응답자들은 [불확실성]을 나타내거나, [지식의 부족]을 다루거나 [양면성을 표현]하기 위해 AD의 중간 "동의하지도 동의하지도 않는다" 범주를 사용할 수 있다. 측정의 관점에서, 응답자들이 중간 범주를 사용하는 것은 문제가 있다: 응답자들은 이 옵션을 신뢰성 있게 선택할 수 있지만, 그들의 응답은 평가되는 구조에 대한 유효한 척도가 아니다. 연구자들은 [AD 중간 범주의 해석]에 문제가 있음을 지적했으며, 종종 이 범주를 중간 값이 아닌 별도로 사용하여 반응을 분석할 것을 제안합니다.

In contrast to unipolar IS items, AD questions often include a clear conceptual middle category (e.g., “neither agree nor disagree”). While experiments evaluating data quality for the inclusion of middle categories for bipolar questions have had mixed results,7,49, 50, 51 studies indicate respondents use the middle category when answering AD questions in unwanted ways. For example, when probed, respondents overwhelmingly reported selecting the middle category because they did not have an opinion on the issue.52,53 Research indicates respondents may use the AD's middle “neither agree nor disagree” category to indicate uncertainty or deal with a lack of knowledge and express ambivalence.4,54,55 From a measurement perspective, respondents use of the “neither/nor” middle category is problematic: while respondents may reliably select this option, their response is not a valid measure of the construct being assessed. Researchers have noted problems with the interpretation of an AD middle category and often suggest analyzing responses using this category separately and not as a middle value.5

배터리

Battery

인지 처리에 관한 섹션에서 설명한 바와 같이, AD 질문이 배터리에 나타날 때 반복적인 응답 범주가 있는 가변 진술로서 그들의 프레젠테이션은 응답자들이 [질문 패턴과 응답 범주를 기억]할 수 있다. 대조적으로, 여러 IS 질문이 함께 그룹화될 때, 그들은 (종종 있지만 항상 그렇지는 않다) 서로 다른 응답 차원과 응답 범주를 사용한다. 배터리 배치, 배터리에 포함된 질문의 수, IS 질문에 대한 질문에 대한 응답 범주가 다양한 정도는 응답자의 인지 노력에 영향을 미치고, 데이터 품질에 영향을 미칠 가능성이 있다. 면접관이 시행하는 설문도구에서 배터리의 항목은 낮은 신뢰성과 관련이 있다. 자기기입식 도구에서 여러 질문이 그리드에 표시될 때, 더 빨리 대답하고 직선에 더 취약하며 더 높은 상관관계를 가질 수 있다. 그리드 표시에서 [상관 관계가 높을수록 공유 오류 분산으로 인한 측정 오류가 더 높다]는 신호를 보낼 수 있습니다.

As described in the section on cognitive processing, when AD questions appear in batteries their presentation as variable statements with repeated response categories allows respondents to memorize the questioning pattern and response categories.32 By contrast, when multiple IS questions are grouped together, they (often, but not always) use different response dimensions and response categories. Placement in a battery, the number of questions contained in the battery, and the extent to which the response categories vary across questions for IS questions are likely to impact respondents’ cognitive effort and affect data quality. In interviewer-administered instruments, items in batteries are associated with lower reliability.56 When multiple questions are presented in a grid in self-administered instruments, they may be answered more quickly, more vulnerable to straightlining,19 and more highly correlated.57 Higher correlations in a grid presentation may signal higher measurement error due to shared error variance.9

발란스 및 정렬

Valence and alignment

구조를 유효하고 안정적으로 측정하기 위해 연구자들은 응답자들의 답변을 결합하여 단일 값을 만드는 [다중 항목 척도]를 사용한다. [구조물의 원자가, 질문에서 평가할 대상의 원자가, 구조물과 질문 사이의 정렬 사이의 관계]는 측정 오류에 대한 암시와 함께 복잡한 관계를 발생시킨다.

In order to measure constructs validly and reliably, researchers use multi-item scales that combine respondents' answers to create a single value.58 Relationships among a construct's valence, the valence of the objects to be evaluated in the questions, and the alignment between the construct and questions gives rise to a complicated set of relationships with implications for measurement error.

[원자가]는 본질적으로 [긍정적, 부정적, 중립적] 또는 [모호한 구조와 질문에서 질문한 대상]을 의미한다. 예를 들어, [신뢰]와 같은 구성 요소는 본질적으로 더 긍정적으로 평가되는 반면, [인종적 분노]와 같은 구성 요소는 더 부정적으로 평가됩니다. 원자가는 척도 내에서 질문에 따라 다르다. [정치적 유효성]을 측정하는 척도의 경우, 공무원들이 사람들이 생각하는 것에 대해 [얼마나 신경을 쓰는지] 묻는 질문은 긍정적으로 평가되고, [정치와 정부가 얼마나 복잡해 보이는지]에 대한 질문은 부정적으로 평가된다.

Valence refers to the inherently positive, negative, neutral, or ambiguous nature of the construct and the objects asked about in the questions. For example, a construct like trust is inherently more positively valenced, while a construct like racial resentment is more negatively valenced. Valence also varies across questions within a scale. For a scale measuring political efficacy,2 a question asking “(how much) public officials care about what people think” is positively valenced, while a question about “(how often) politics and governments seem so complicated people can't really tell what's going on” is negatively valenced.

[정렬]은 반응 범주가 구조의 더 낮은 값을 나타내는지 또는 더 높은 값을 나타내는지 여부를 나타냅니다. [포지티브 정렬] 항목은 [더 높은 값의 범주(예: AD 질문에 대해 "강력하게 동의"하고 IS 질문에 대해 "대단히 동의")가 측정되는 구조의 더 높은 수준]을 나타내는 항목이며, [네거티브 정렬] 항목은 [더 높은 값의 범주가 더 낮은 수준]을 나타내는 항목이다. 예를 들어, 가장 값이 높은 범주("강력하게 동의한다"와 "대단히 동의한다")가 가장 높은 수준의 정치적 효과를 나타내기 때문에 [사람들이 무엇을 생각하는지에 대한 공무원들의 관심에 대한 질문]은 긍정적으로 일치한다. 대조적으로, 가장 높은 값의 범주는 가장 낮은 수준의 정치적 효능을 나타내기 때문에 [정치와 정부에 대한 질문]은 부정적으로 일치할 것이다.

Alignment refers to whether lower- or higher-valued response categories indicate lower or higher values of the construct. Positively aligned items are those for which a higher-valued category (e.g., “strongly agree” for an AD question and “a great deal” for an IS question) indicate higher levels of the construct being measured and negatively aligned items are those for which a higher-valued category indicates lower levels of the construct. For example, the question about public officials caring what people think would be positively aligned because the highest-valued categories (“strongly agree” and “a great deal”) indicate the highest level of political efficacy. By contrast, the question about politics and governments would be negatively aligned because the highest-valued categories indicate the lowest level of political efficacy.

AD 질문의 경우 질문의 값은 [묵인]으로 인해 원하지 않는 응답 효과를 초래할 수 있습니다. [긍정적으로 평가된 구조와 질문]의 경우, 묵인은 반응과 구조를 실제보다 더 긍정적으로 보이게 할 수 있다; [긍정적으로 평가된 구조와 부정적으로 단어가 쓰인 질문]에 대해, 묵인은 반응과 구조를 더 부정적으로 보이게 만들 수 있다. [우울증]과 같이 [부정적으로 평가된 구조]의 경우, 구조에 대한 더 높은 값을 나타내기 위해 정렬된 항목(예: "나는 슬프고 우울했다")에 동의하는 경향은 구조에 대한 과대평가를 초래할 수 있다. 항목의 점수를 매기는 방법에 따라, 묵인은 다음을 유발할 수 있다: 평균 점수 추정치 부풀리기, 신뢰도 추정치의 인위적 인플레이션/디플레이션(특히 같은 방향으로 단어가 표시된 항목의 경우), 그리고 AD 측정과 기준 측정 사이에 [자극적으로 높은 상관관계]를 만든다.

For AD questions, a question's valence can lead to undesired response effects due to acquiescence.

- For positively valenced constructs and questions, acquiescence can make responses and constructs appear more positive than they are in reality;

- for positively valenced constructs and negatively worded questions, acquiescence can make responses and constructs appear more negative.

For more negatively valenced constructs like depression, a tendency to agree with items that are aligned to indicate higher values for the construct (e.g., “I have felt sad and blue”), can lead to overestimates of the construct. Depending on how items are scored, acquiescence can inflate estimates of mean scores, artificially inflate or deflate reliability estimates (particularly for items worded in the same direction), and create spuriously high correlations between AD measures and criterion measures.59, 60, 61

[묵인(그리고 부주의)으로 인한 효과]를 줄이기 위해 연구자들은 종종 [긍정적으로 정렬된 항목]과 [부정적으로 정렬된 항목]("항목 반전" 및 역어 질문이라고도 함)을 모두 포함하는 척도를 만들 것을 권장한다. 이 접근법의 이면에 있는 논리는 묵인하는 사람들을 반응 분포의 중간에 배치함으로써 척도 평균의 편향을 줄일 것이라는 것이다. 그러나 연구에 따르면 이 접근법에는 몇 가지 문제가 있다.

- 첫째, 모든 응답자에게 동일한 의미를 전달하는 부정적인 단어의 질문을 작성하는 것은 어려울 수 있다 (예: "흥미롭다"의 반대를 측정하기 위해 연구자는 "흥미없다", "흥미없다", "흥미없다" 또는 "흥미없다"를 사용할 수 있지만, 이들이 응답자들 사이에서 동일한 의미를 가질 가능성은 낮다. 그리고 반대로 단어가 쓰인 항목을 포함하는 것은 응답자가 해당 항목에 대해 반대로 쓰지 않은 경우만큼 극단적으로 대답하는 경우에만 편향을 줄일 것이다.).

- 둘째, "아니다", "un-", "non-", "-less"와 같은 부정의 사용은 이해성과 데이터 품질을 저하시킬 수 있다. 이것은 진술서에 부정을 포함하는 것(예: "내 성별은 다른 사람들이 나를 대하는 방식에 영향을 미치지 않는다")이 진술서의 내용을 거부하기 위해 [이중 부정]을 처리해야 하는 AD 항목에서 특히 문제가 될 수 있다.

- 셋째, 척도의 균형을 맞추려는 시도는 척도의 타당성과 내부 일관성을 낮추고, 부정적으로 정렬된 항목에 대해 예기치 않은 요인 구조를 만들어 [방법 효과method effect]를 추가하는 등 방법론적 문제를 야기할 수 있다.

In order to reduce effects due to acquiescence (and inattention), researchers often recommend creating scales that include both (and often an equal number of) positively and negatively aligned items62, 63, 64 (also called “item reversals”64 and reverse-worded questions65). The logic behind this approach is that it will reduce bias in scale means by placing those who acquiesce in the middle of the response distribution. However, research indicates several problems with this approach.

- First, writing negatively worded questions that convey the same meaning across all respondents can be difficult (e.g., to measure the opposite of “interesting,” a researcher could use “not interesting,” “uninteresting,” or “boring,” but it is unlikely these have the same meaning across respondents and including oppositely worded items will only reduce bias if respondents answer those items as extremely as they would their counterparts66).

- Second, the use of negations like “not,” “un-,” “non-,” and “-less” may decrease comprehensibility and data quality.67,68 This may be particularly problematic for AD items where the inclusion of a negation in the statement (e.g., “My gender does not affect the way others treat me”) requires processing a double negative in order to reject the statement's contents (e.g., by selecting “disagree”).69,70

- Third, attempts at balancing scales may create methodological problems including lowering the validity and internal consistency of the measures and adding a method effect by creating an unexpected factor structure for the negatively-aligned items.71, 72, 73, 74

의견, 권장 사항 및 향후 방향에 대한 마무리

Concluding comments, recommendations, and future directions

AD 질문과 IS 질문을 비교한 실험 연구의 한계

Limitations of experimental studies comparing AD and IS questions

전반적으로 IS 질문은 바람직한 데이터 품질 결과(유효성, 신뢰성)와 관련이 있으며 AD 질문은 바람직하지 않은 결과(인수, 대응 효과 등)와 관련이 있다는 연구 결과가 더 많다. 그러나 많은 연구에서 질문 유형 간의 차이를 발견하지 못했으며, 일부 연구에서는 IS 질문에 대해 더 높은 수준의 바람직하지 않은 결과를 발견했다. 이러한 비교 연구의 몇 가지 한계는 일관성이 없거나 무효인 결과를 설명할 수 있다.

- 첫째, AD와 IS 문제를 비교하는 실험 연구의 수가 상대적으로 적다. 우리의 리뷰는 20개의 연구를 확인했다.

- 둘째, 질문 특성에 대한 논의에서 강조된 바와 같이 AD-IS 질문 쌍은 대개 제어되지 않는 여러 특성에 걸쳐 종종 달라지며, 이는 결과를 혼란스럽게 할 수 있다.

- 셋째, 연구는 제한된 수의 주제를 탐구하며 AD 및 IS 질문의 효과는 주제별로 다를 수 있다.

Overall, more studies find IS questions are associated with desirable data quality outcomes (validity, reliability) and AD questions are associated with undesirable outcomes (acquiescence, response effects, etc.). A number of studies, however, find no differences between the question types, and a few studies find higher levels of undesirable outcomes for IS questions. Several limitations of these comparative studies may account for inconsistent or null findings.

- First, the number of experimental studies comparing AD and IS questions is relatively small. Our review identified twenty studies.

- Second, highlighted in our discussion of question characteristics, AD-IS question pairs often vary across a number of characteristics that are usually not controlled for, which may confound the results.

- Third, studies explore a limited number of topics and the effects of AD and IS questions may vary by topic.

넷째, 연구는 타당성, 신뢰성, 묵인, 직선화 등 다양한 데이터 품질 결과를 조사한다. 이러한 결과는 강도와 조작화 측면에서 다양합니다. 타당도와 신뢰도의 추정치는 잠재적으로 데이터 품질에 대한 보다 직접적인 측정치를 제공하지만, 연구는 품질에 따라 달라지는 [신뢰도와 타당도의 다양한 측정치]를 평가한다. 예를 들어, [Cronbach 알파]와 같은 척도의 항목 신뢰도 추정치에는 상관된 오차 분산이 포함되어 있으며 개별 항목에 대한 값을 제공하지 않습니다. 일반적으로 사용되는 짧은 간격 동안 추정된 [시험 재시험 신뢰도]은 강력한 기준을 제공하기 위해 [기억 효과] 또는 [신뢰할 수 있는 방법 효과]에 의해 지나치게 손상될 수 있다. 묵인, 응답 범주의 반복 및 배터리의 항목 표시의 조합은 AD 항목 집합 간의 상관 방법 분산을 증가시킬 수 있으며, 이는 [단순한 상관 관계가 근본적으로 데이터 품질의 모호한 지표임]을 상기시킨다. [방법분산method variance]은 AD와 IS 항목의 상대적 품질을 평가하는 데 중심이 되므로, 방법분산을 파악할 수 있는 신뢰성 추정 및 구성타당성을 위한 방법이 필요하다.

Fourth, studies examine many different data quality outcomes: validity, reliability, acquiescence, straightlining, etc. These outcomes vary in terms of their strength and operationalizations. While estimates of validity and reliability potentially offer more direct measures of data quality, studies evaluate different measures of reliability and validity that vary in their quality. For example, estimates of reliability of items in a scale, such as from Cronbach's alpha, include correlated error variance and do not provide values for individual items. Estimated test-retest reliabilities, over the short intervals that are commonly used, may be too compromised by memory or reliable method effects to provide a strong criterion.56 It is plausible that a combination of acquiescence, the repetition of the response categories, and the presentation of items in a battery increases correlated method variance among a set of AD items, a reminder that simple correlations are fundamentally an ambiguous indicator of data quality. Because method variance is central to evaluating the relative quality of AD and IS items, methods for estimating reliability and construct validity that can identify method variance are needed.14

질문 특성에 대한 개요를 통해 알 수 있는 내용

What the overview of question characteristics tells us

AD-IS 실험에 포함된 AD-IS 질문 간에 달라지는 핵심 질문 특성에 대한 분석은 이러한 실험에서 비교되는 질문이 종종 여러 특성에 따라 달라져 결론을 도출하는 능력을 복잡하게 만든다는 사실을 강조한다. 한 연구에서 연구자들은 신뢰도를 측정하는 AD-IS 쌍이 다음에 따라 차이가 있다고 지적했습니다:

- 제공된 응답 차원 (IS 질문에 대한 응답 치수가 설계 및 측정된 강도, 빈도 및 양에 따라 문항특이적인 반면, AD 질문은 강도를 측정했다.);

- 응답 범주의 방향성 (AD 대응 범주는 높은 순서에서 낮은 순서로 정렬 – "강력히 동의"에서 "강력히 반대"로 정렬 – IS 범주는 "전혀"에서 "매우"로, "절대"에서 "항상"으로 정렬됨);

- 극성 (AD 질문은 양극성, IS 질문은 단극성).

Our analysis of the key question characteristics that vary between AD-IS questions included in AD-IS experiments highlights the fact that in these experiments, the questions being compared often vary on a number of characteristics, complicating our ability to draw conclusions. In one study,4 researchers noted their AD-IS pairs measuring trust varied based on:

- offered response dimensions (the AD questions measured intensity while the response dimensions for the IS questions were item-specific by design and measured intensity, frequency, and quantity);

- the direction of the response categories (the AD response categories were ordered from high to low – “strongly agree” to “strongly disagree” – while the IS categories were ordered from low to high – “not at all” to “a great deal,” “never” to “always”);

- polarity (the AD questions were bipolar; the IS questions were unipolar).

이 두 응답 형식 사이의 구조적 차이는 응답자의 인지 처리와 데이터 품질에 중요한 결과를 초래한다. 현재까지 이러한 특성의 모든 고유 효과 또는 결합 효과를 추정할 수 있는 설계를 특징으로 하는 연구는 없습니다. 실제로, 응답 범주의 수 또는 척도 방향과 같이 데이터 품질에 중요할 가능성이 있는 다른 특성에서 체계적인 변화가 있는 AD-IS 응답 형식의 사용을 건너는 실험은 소수에 불과하다. 이러한 연구의 결과는 궁극적으로 AD-IS 응답 형식과 다른 질문 특성 사이의 체계적인 상호 작용을 밝혀낼 수 있다.

The structural differences between these two response formats have important consequences for respondents’ cognitive processing and data quality. To date, no studies feature a design that allows for estimation of all the unique or joint effects of these characteristics. Indeed, only a handful of experiments cross the use of an AD-IS response format with systematic variation in other characteristics that are likely to be important for data quality, such as the number of response categories or scale direction. Findings from such studies may ultimately uncover systematic interactions between AD-IS response formats and other question characteristics.

AD 질문을 IS 질문으로 변환할 때의 과제

Challenges of translating AD questions to IS questions

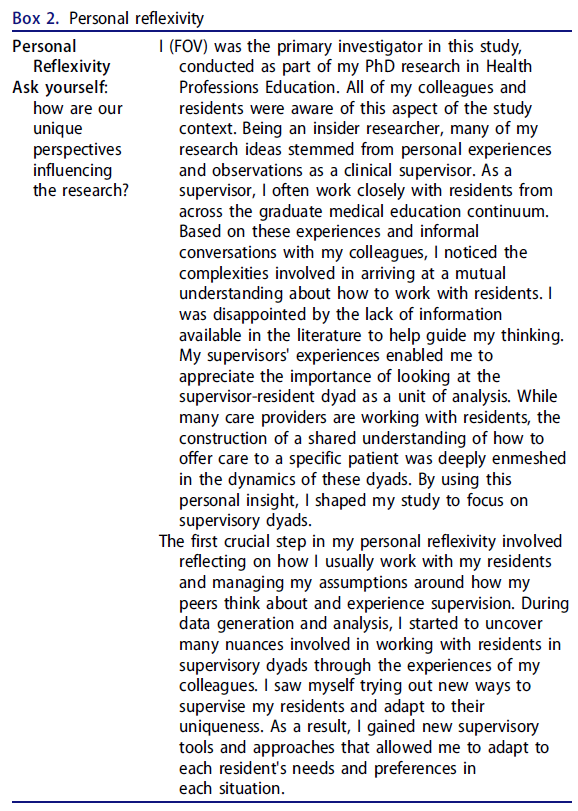

새로운 연구를 위한 주관적 평가를 측정하기 위한 질문을 작성할 때, 여기에 제시된 문제는 IS 질문을 사용하는 것을 권장합니다. 그러나 많은 연구는 이전에 관리된 설문지의 항목을 사용하는 것을 목표로 하며 AD 형식에서 IS 형식으로 번역하는 것은 여러 가지 과제를 제기할 수 있다. AD 문은 상대적으로 작성하기 쉽기 때문에 동시에 평가해야 할 여러 요소(예: 여러 대상 객체 및 조건문)를 포함하는 경우가 많습니다. GSS의 다음 AD 질문을 고려해 보십시오:

"과거의 차별 때문에, 고용주들은 자격 있는 여성들을 고용하고 홍보하기 위해 특별한 노력을 해야 합니다."

이 질문은 몇 가지 사항에 대해 묻는다:

- 차별의 원인(예: 성별)과 대리인(예: 고용주)에 대한 믿음,

- 과거의 차별에 대한 보상을 해야 하는 고용주의 책임,

- 자격을 갖춘 여성을 고용하고 승진시키는 것이 과거의 행동을 바로잡는지 여부.

When writing questions to measure subjective evaluations for a new study, the issues presented here recommend using IS questions. Many studies, however, aim to use items from previously administered questionnaires and translating from an AD to IS format can pose a number of challenges. Because AD statements are relatively easy to write, they often include several elements – such as multiple target objects and conditional statements -- to be evaluated simultaneously.42 Consider, the following AD question from the GSS:

“Because of past discrimination, employers should make special efforts to hire and promote qualified women.”

This question asks about several things:

- beliefs about the causes (e.g., gender) and agents of discrimination (e.g., employers),

- the responsibility of employers to make amends for past discrimination, and

- whether hiring and promoting qualified women rectifies past behavior.

이 진술에 대한 [동의 또는 동의하지 않는 것]은 이러한 [구성요소 또는 이들의 조합에 대한 믿음]에 기초할 수 있다. 이 질문을 IS 형식으로 변환하면 기본 응답 차원에 대해 내려야 하는 항목과 결정의 복잡성이 강조됩니다: 강도(얼마나 특별한 노력이 필요한가), 양(얼마나 많은 노력이 필요한가), 빈도(얼마나 자주 노력이 필요한가)에 대한 질문인가?

Agreement or disagreement with this statement could be based on beliefs about any of these components or combinations of them. Translating this question into an IS format underscores the complexity of the item and decisions that must be made about the underlying response dimension: is the question asking about intensity (how special efforts should be), quantity (how much effort should be made), or frequency (how often efforts should be made)?

데이터 품질 저하의 원인이 될 수 있는 AD 질문과 관련된 문제는 기본 응답 차원이 모호하거나 여러 해석에 열려 있는 방식으로 작성되는 경우가 많다는 것이다. GSS에서 추출하여 정치적 효과를 측정하도록 설계된 척도에 포함된 표 3의 AD 질문을 고려해 보십시오. 임계값 단어 "most"가 수량 응답 차원을 의미하는 반면 AD 문은 강도, 수량 또는 빈도 차원을 사용하여 IS 질문으로 쉽게 번역될 수 있으며, 실제로 가능한 두 가지 수량 차원인 "얼마나"와 "얼마나 많은"가 가능합니다.

A related problem with AD questions that likely contributes to their lower data quality is that they are often written in way that leaves their underlying response dimension ambiguous or open to multiple interpretations.6 Consider the AD question in Table 3, taken from the GSS and included in a scale designed to measure political efficacy. While the threshold word “most” implies a quantity response dimension, the AD statement can easily be translated into IS questions using intensity, quantity, or frequency dimensions, and indeed, two possible quantity dimensions – “how much” and “how many” are possible.

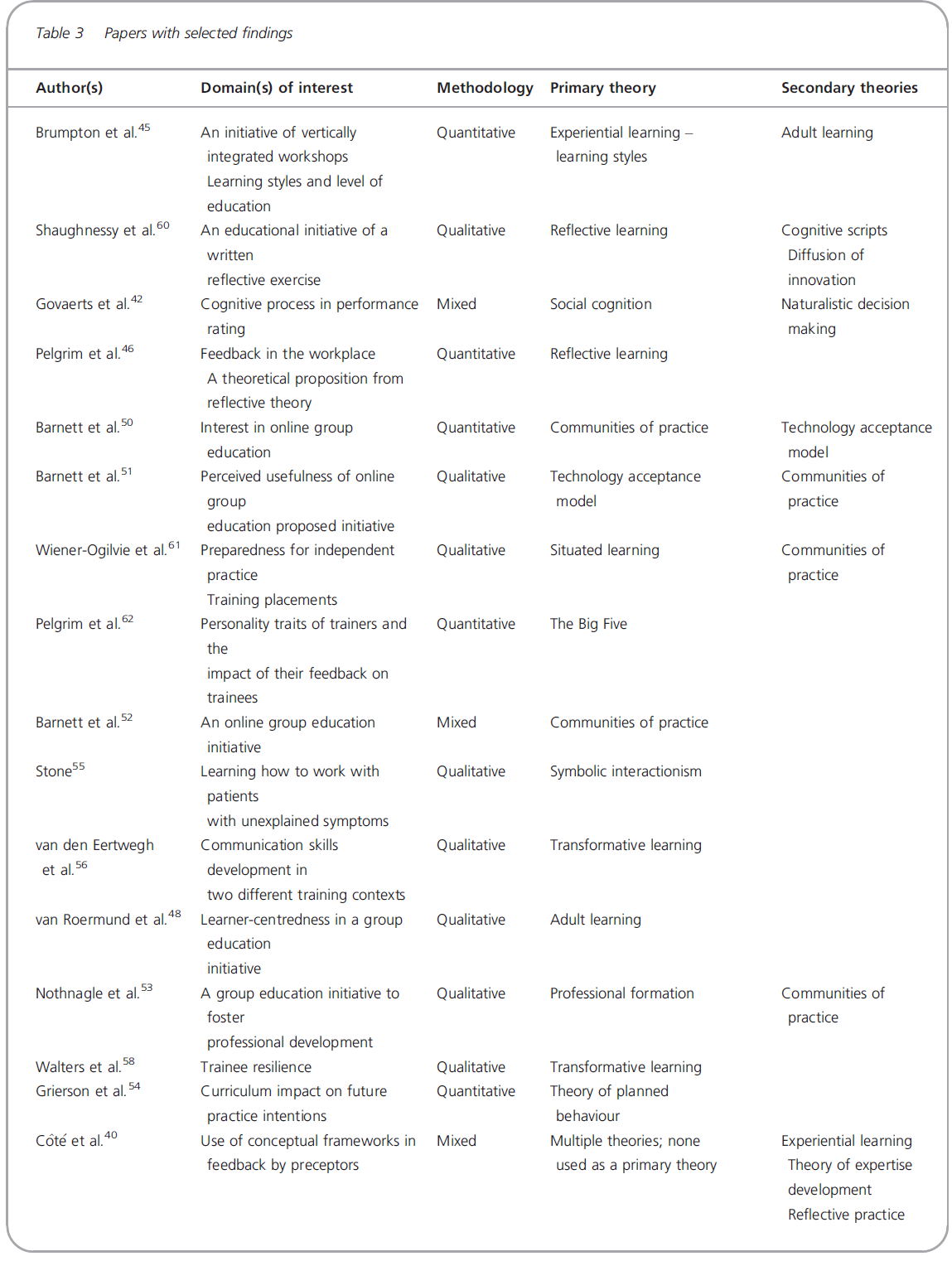

AD 질문은 항목이 완전히 다른 주제에 대해 질문하는 경우에도 동일한 응답 범주를 사용하여 많은 항목을 배터리로 결합할 수 있기 때문에 널리 사용됩니다. 자체 관리를 위해 AD 질문을 그리드 형식으로 지정하여 공간을 최소화할 수 있습니다. 그러나 IS 질문은 질문의 기본 응답 차원과 일치하는 응답 범주를 사용하기 때문에 AD에서 IS로 항목 집합을 변환하면 문항이 동일한 기본 응답 차원을 공유하지 않는 경우가 많습니다. 예를 들어 표 4의 6개 AD 항목은 그리드에 압축된 동일한 응답 범주를 사용하는 반면, IS 대응 항목은 강도, 양 및 빈도에 대한 응답 차원을 사용하고 해당 차원과 관련된 응답 범주를 요구합니다. IS 항목을 결합하면 그리드가 약간 더 길어집니다. 시각적으로 긴 그리드는 응답자들에게 더 부담스러운 것으로 인식될 수 있지만, 더 명확하게 작성되고 이해하기 쉽기 때문에 IS 질문은 덜 부담스러울 가능성이 높다. AD 및 IS 질문에 답하면서 응답자의 인지적 노력을 측정하고 노력 척도를 데이터 품질과 직접 연결하는 연구가 더 필요하다.

AD questions are widely used because many items can be combined into a battery using the same response categories, even if the items ask about completely different topics. For self-administration, AD questions can be formatted in a grid to minimize space. However, because IS questions use response categories that match the questions' underlying response dimensions, translating a set of items from AD to IS often reveals that the items do not share the same underlying response dimension. For example, while the six AD items in Table 4 use the same response categories, compactly formatted in the grid,11 their IS counterparts use response dimensions for intensity, quantity, and frequency and require response categories relevant for those dimensions. When combined, the IS items result in a slightly longer grid. While a visually longer grid may be perceived by respondents as more burdensome, because they are more clearly written and easier to understand, the IS questions are likely less burdensome. More research measuring respondents’ cognitive effort while answering AD and IS questions and directly linking effort measures to data quality is needed.

질문 작성자는 종종 [개정과 복제의 균형]을 맞춰야 한다. AD 질문의 광범위한 사용을 고려할 때, 연구자들은 시계열 데이터의 추세 손실을 포함하여 [이전에 시행된 질문이나 "검증된" AD 척도를 사용하지 않는 것에 대한 단점]과 [데이터 품질의 잠재적인 이점]을 비교하여 IS 측정을 변환하는 것을 고려해야 할 수 있다. 검증된 계측기 개발과 관련된 많은 문제가 이 검토의 범위를 벗어나지만, 우리는 척도의 타당화는 이분법적 결과가 아니라 프로세스임을 독자들에게 상기시키고자 한다. 특정 목적을 위해 특정 모집단에 대해 검증된 도구는 증거 없이 다른 모집단이나 목적으로 확장되지 않을 것이다. 또한, 많은 "타당화된" 계측기는 [표준화된 측정을 위한 질문 작성]에 [근거-기반 표준에 미달하는 질문]을 사용한다.

Question writers often need to balance revision against replication.69 Given the wide-spread use of AD questions, researchers may need to weigh disadvantages of not using previously administered questions or “validated” AD scales, including losing trends from time-series data, versus potential gains in data quality to converting IS measures. While many issues related to developing a validated instrument75,76 are beyond the scope of this review, we remind readers that instrument validation is not a binary outcome, but a process.77 An instrument validated for a specific population for a specific purpose would not – without evidence – extend to a different population or purpose. Further, many “validated” instruments use questions that fall short of evidenced-based standards for writing questions for standardized measurement.9

미래연구

Future research

AD와 IS 응답 형식을 직접 비교하는 실험 연구는 약간의 혼합된 결과를 산출하지만, IS 형식을 지지하는 강력한 이론적 뒷받침과 이용 가능한 증거를 고려할 때, 우리는 대부분의 목적으로 AD 질문보다 IS 질문을 추천한다. 우리의 검토는 또한 다양한 실질적 주제에 걸쳐 AD와 IS 질문을 비교하고 데이터 품질을 평가하기 위한 강력한 기준을 포함하는 설계가 더 많은 실험적 연구의 필요성을 지적한다. 향후 작업은 다음 사항을 우선시해야 합니다:

Although experimental studies directly comparing AD and IS response formats yield some mixed results, given the strong theoretical underpinning and available evidence in support of the IS format, we recommend IS questions over AD questions for most purposes. Our review also points to the need for more experimental research comparing AD and IS questions across a range of substantive topics and with designs that incorporate strong criteria to evaluate data quality. Future work should prioritize the following:

1) 특정 특성을 가진 일부 구문 또는 질문은 AD 질문으로 더 잘 측정됩니까?

1) Are some constructs or questions with specific characteristics better measured with AD questions?

Dykema 등은 [의학 연구자에 대한 신뢰]와 같은 비특이적 구성에 대해 질문할 때, 빈도-기반 응답 차원을 사용하는 질문을 할 때, 특히 외부에 초점을 맞춘 행위자들(예: "의학 연구자들은 연구 참가자들의 안전을 보장하기 위해 얼마나 열심히 일하고 있는가")에 대해 질문할 때, 응답자들은 [평가를 위한 것]이 아니라, [대상 물체에 대한 지식을 묻는 것]처럼 들렸기 때문에 응답자들에게 어려웠다. 리커트가 초기 연구에서 사용한 진술과 유사하게, [동의-비동의 보기]는 "해야 한다"(예: "성인 자녀는 부모가 나이가 들면 부모를 돌봐야 한다")를 사용하는 [가치 진술]에도 적용하기 쉬울 수 있다.

Dykema et al.4 noted that when asking about a non-salient construct like trust in medical researchers, questions using frequency-based response dimensions, especially when asking about externally-focused actors (e.g., “how hard do medical researchers work to ensure participants in their studies are safe”), were difficult for respondents because they sounded like they were asking respondents about their knowledge of the target object and not for an evaluation.78 Similar to the statements Likert used in his early work, an agreement response dimension may also be easy to apply to statements of values using “should” (e.g., “Adult children should take care of their parents when the parents become old”).

2) 어떤 특성 조합이 최상의 데이터 결과를 제공합니까?

2) What combinations of characteristics yield the best data outcomes?

우리는 어떤 조합이 최고 품질의 데이터를 산출하는지 결정하기 위해 연구자들에게 특정 질문 특성과 특성 조합의 효과를 추정할 수 있는 능력을 제공할 수 있는 다요인 설계를 사용한 향후 작업을 권장한다.

We encourage future work using multifactorial designs that can provide researchers with the ability to estimate the effects of particular question characteristics and combinations of characteristics in order to determine which combinations yield the highest quality data.

3) AD 및 IS 질문의 측정 특성은 교육, 언어 구어 및 연령과 같은 사회 인구 통계적 특성에 따라 그룹마다 어느 정도 차이가 있습니까? 많은 연구들은 묵인과 같은 원치 않는 반응 효과가 낮은 교육을 받은 응답자들 사이에서 더 높다는 것을 보여주지만, AD 또는 IS 형식이 그러한 효과로부터 더 보호할 가능성이 있는지를 조사하는 연구는 거의 없다.

3) To what extent do the measurement properties of AD and IS questions vary across groups based on socio-demographic characteristics such as education, language spoken, and age? Many studies demonstrate that unwanted response effects like acquiescence are higher among respondents with lower education,38,39 but few studies examine whether an AD or IS format is more likely to protect against such effects.

4) AD 및 IS 응답 형식은 관리 모드와 어떻게 상호 작용하며, 어떤 형식이 어떤 모드에 최적이며, 모드 내에서 어떤 구현 기능이 측정에 영향을 미칩니까? 인터뷰어-설문진행의 한계는 응답자가 응답 범주를 인코딩하고 호출해야 한다는 것입니다. 대면 인터뷰 중 IS 아이템에 대한 쇼케이스를 제공하면 응답자의 인지 부담을 줄일 수 있지만, IS아이템 솔루션은 전화 인터뷰에 쉽게 적용되지 않으며, 다양한 응답 범주를 가진 많은 항목을 포함하는 IS 척도는 응답자에게 어려울 수 있다.

4) How do AD and IS response formats interact with the mode of administration, which format is optimal for which modes, and which features of implementation within mode have consequences for measurement? A limitation of interviewer-administration is that respondents must encode and recall response categories. While providing showcards for IS items during in-person interviews may reduce respondents’ cognitive burden, this solution is not easily applicable to phone interviews and IS scales that include many items with variable response categories may be difficult for respondents.

또한, 그리드를 독립형 질문으로 대체하여 수평 스크롤을 제한하는 응답성 설계를 사용하는 모바일 장치에서 설문 조사가 완료되어 그리드의 이점이 무효화된다. 모드와 관련된 문제는 모드를 혼합하는 조사가 증가하고 연구자들이 모드 효과를 측정하고 줄이는 방법을 계속 탐구함에 따라 더 많은 정밀 조사를 받게 될 것이다. 권장 사항은 점점 더 강력한 연구가 가능해지면 변경될 수 있지만, 현재 우리가 가지고 있는 가장 강력한 증거는 IS 아이템이 더 높은 품질의 데이터를 산출하고 연구자들에게 설계에 있어 상당한 유연성을 제공할 것임을 시사한다.

Further, an increasing share of surveys are completed on mobile devices which usually use a responsive design that limits horizontal scrolling by replacing grids with stand-alone questions, rendering any advantages of grids null. Issues related to mode are likely to receive increased scrutiny as surveys that mix modes grow and researchers continue to explore methods to measure and reduce mode effects.79, 80 Although recommendations may change when more and stronger research becomes available, the strongest evidence we currently have suggests that IS items will yield higher quality data and offer researchers considerable flexibility in design.

Towards a reconsideration of the use of agree-disagree questions in measuring subjective evaluations

PMID: 34253471

PMCID: PMC8692311 (available on 2023-02-01)

Abstract

Agree-disagree (AD) or Likert questions (e.g., "I am extremely satisfied: strongly agree … strongly disagree") are among the most frequently used response formats to measure attitudes and opinions in the social and medical sciences. This review and research synthesis focuses on the measurement properties and potential limitations of AD questions. The research leads us to advocate for an alternative questioning strategy in which items are written to directly ask about their underlying response dimensions using response categories tailored to match the response dimension, which we refer to as item-specific (IS) (e.g., "How satisfied are you: not at all … extremely"). In this review we: 1) synthesize past research comparing data quality for AD and IS questions; 2) present conceptual models of and review research supporting respondents' cognitive processing of AD and IS questions; and 3) provide an overview of question characteristics that frequently differ between AD and IS questions and may affect respondents' cognitive processing and data quality. Although experimental studies directly comparing AD and IS questions yield some mixed results, more studies find IS questions are associated with desirable data quality outcomes (e.g., validity and reliability) and AD questions are associated with undesirable outcomes (e.g., acquiescence, response effects, etc.). Based on available research, models of cognitive processing, and a review of question characteristics, we recommended IS questions over AD questions for most purposes. For researchers considering the use of previously administered AD questions and instruments, issues surrounding the challenges of translating questions from AD to IS response formats are discussed.

Copyright © 2021 Elsevier Inc. All rights reserved.

'Articles (Medical Education) > 의학교육연구(Research)' 카테고리의 다른 글

| 질적연구에서 포화를 위한 표본 수: 실증 시험의 체계적 문헌고찰(Soc Sci Med. 2022) (0) | 2023.03.17 |

|---|---|

| 양적연구 질문과 질적연구 질문 및 가설 작성의 실용 가이드 (J Korean Med Sci. 2022) (0) | 2023.03.04 |

| 크리스마스 2022: 과학자: 크리스마스 12일째날, 통계학자가 보내주었죠(BMJ, 2022) (0) | 2023.01.15 |

| 설문에서 최대한을 얻어내기: 응답 동기부여 최적화하기(J Grad Med Educ. 2022) (0) | 2023.01.15 |

| 구색만 갖추기: 어거지로 하는 설문이 자료 퀄리티에 미치는 영향(EDUCATIONAL RESEARCHER, 2021) (0) | 2023.01.15 |