학부의학교육에서 지속적 질 개선의 문화 만들기(Acad Med, 2020)

Shaping a Culture for Continuous Quality Improvement in Undergraduate Medical Education

Guy W.G. Bendermacher, MSc, Willem S. De Grave, MSc, PhD, Ineke H.A.P. Wolfhagen, MSc, PhD, Diana H.J.M. Dolmans, MSc, PhD, and Mirjam G.A. oude Egbrink, MSc, PhD

지속적인 질 향상(CQI) 전략은 커리큘럼이 발전하는 대중의 요구, 근거 기반 의학, 효과와 효율성에 대한 관심 증가에 발맞춰야 한다는 점에서 의과대학에 매우 중요합니다.1,2 1990년대 초부터 의과대학은 질 관리 접근 방식에 상당한 투자를 해왔으며, 그 결과 직원 성과에 대한 더 나은 통찰력, 개선이 필요한 주제를 알리는 기회, 더 명확하게 정의된 책임 등을 확보할 수 있었습니다.3,4

Continuous quality improvement (CQI) strategies are of key importance to medical schools, given the need for curricula to keep pace with advancing public demands, evidence-based medicine, and an increased attention to effectiveness and efficiency.1,2 Since the early 1990s, medical schools have invested considerably in quality management approaches, resulting in better insights in staff performance, further opportunities to signal topics for improvement, and more clearly defined responsibilities.3,4

CQI는 학교가 교육의 질에 대한 다양한 개념을 체계적으로 다루기 위해 도전하는 상태와 유사합니다. 이해관계자의 관점에 따라 교육의 질은 다음과 같이 이해할 수 있습니다.5

- 목적 적합성(유능한 미래 의사 교육),

- 비용 대비 가치(교육에 대한 투자 수익),

- 완벽성(결함 제로에 집중),

- 탁월성(최고의 프로그램으로 우뚝 서기),

- 혁신성(교육 학습 효과에 집중)

계획-실행-점검(PDCA) 사이클과 같은 실행 프레임워크는 CQI가 반복적이고 점진적인 과정임을 설명해줍니다. PDCA 사이클에서는 교육 결과를 미리 정해진 목표와 비교하고, 평가를 바탕으로 격차를 해소하기 위한 조치를 취할 수 있습니다.6

CQI resembles a state in which schools take on the challenge to address different notions of educational quality in a methodical manner. Depending on the perspective of a stakeholder, educational quality can be understood as

- fitness for purpose (educating capable future physicians),

- value for money (a return on investment in education),

- perfection (focusing on zero defects),

- exceptional (standing out as the best program), or

- transformative (focusing on the educational learning effect).5

Implementation frameworks such as the plan–do–check–act (PDCA) cycle illustrate that CQI is a repetitive and incremental process. The PDCA cycle holds that educational outcomes are compared to predetermined goals and that based on evaluations, action can be taken to address disparities.6

현재의 품질 관리 접근법의 긍정적인 효과에도 불구하고 교육 개선이 간단한 과정이 아니라는 공감대가 확산되고 있습니다.7 이 개념을 뒷받침하는 세 가지 주요 주장이 있습니다.

- 첫째, 질 관리 시스템과 프로세스의 성공 여부는 교수진, 지원 직원 및 학생이 이를 구현하고 수용하는 방식에 달려 있습니다.8 예를 들어, 학문적 자유의 전통은 프로그램 평가의 판단적 성격과 상충될 수 있습니다.9

- 둘째, 의과대학은 다양한 하위 문화를 포함하는 복잡하고 계층적인 조직입니다.10 이러한 특성은 개선 노력에 대한 집단적 참여를 방해합니다.11

- 셋째, CQI는 이용 가능한 정보, 시간 및 인센티브에 의해 제한됩니다.12 교육 개선을 위한 추가 노력에 대한 보상이 부족하면 평가가 구체적인 행동으로 이어지지 않는 이유를 설명할 수 있습니다.13

Notwithstanding the positive effects of current quality management approaches, there is a growing consensus that educational improvement is not a straightforward process.7 Three main arguments underpin this conception.

- First, the success of quality systems and processes depends on the way they are implemented and received by faculty, support staff, and students.8 Traditions of academic freedom, for instance, can stand at odds with the judgmental character of program evaluations.9

- Second, medical schools are complex, hierarchical organizations, which include different subcultures.10 These characteristics hamper a collective engagement in improvement efforts.11

- Third, CQI is bounded by available information, time, and incentives.12 The lack of rewards for extra efforts to improve education can explain why evaluations are not followed up with concrete actions.13

CQI를 위한 구조와 프로세스는 교육의 질에 대한 관심을 핵심으로 하는 조직(하위)문화에 의해 보완되어야 한다는 생각은 질 문화 개념의 토대를 형성합니다.14,15 이 개념은 조직문화가 "외부 적응과 내부 통합의 문제에 대처하는 방법"16 을 반영한다는 관점과 연결되며 조직(하위)문화와 성과에 대한 이전 연구를 기반으로 합니다.17

- 질 문화는 신뢰와 참여를 촉진하고

- 리더십과 커뮤니케이션은 하드(시스템 또는 프로세스 지향)와 소프트(심리적 또는 가치 관련 지향) 차원 간의 연결을 강화할 수 있습니다.18,19

The idea that structures and processes for CQI should be complemented by an organizational (sub)culture with care for educational quality at its core forms the foundation of the quality culture concept.14,15 This concept is linked to the perspective that organizational cultures reflect “a way to cope with problems of external adaptation and internal integration,”16 and builds on previous research on organizational (sub)culture(s) and performance.17

- A quality culture promotes trust and involvement, while

- leadership and communication can reinforce the link between its hard (system or process oriented) and soft (psychological or value-related oriented) dimensions.18,19

여러 연구가 질 문화 개념을 더 잘 정의하는 데 기여했으며20,21 고등 교육 내 하위 문화를 식별했습니다.22,23 또한 이전 연구는 질 관리의 성공이 문화적 요인 및 교수진 선호와의 얼라인먼트로 설명될 수 있다는 통찰에 기여했습니다.24,25 그러나 품질 문화에 대한 대부분의 연구는 이론적이고 설명적인 성격을 띠고 있습니다.19 질 정책 및 절차에 참여하는 학생과 교수진이 질 문화를 개념화하는 방식에 대한 실증적 연구가 부족합니다. 특히, 업무와 관련된 심리적 태도가 질 관리 및 책임 절차에 어떤 영향을 미치는지에 대한 교육기관 전반의 통찰력 강화가 필요합니다. 이 분야에 대한 지식의 증대는 품질 문화 육성의 장점을 뒷받침할 것입니다. 본 연구는 조직의 질 문화의 주요 특징이 무엇이며 이러한 특징이 학부 의학교육의 지속적인 개선에 어떻게 기여하는지에 대한 질문을 다룹니다. 의과대학의 CQI 시스템과 프로세스가 점점 더 유사해지고 있는 가운데, 우리는 주로 업무 관련 심리적 태도와 조직 가치 지향성이 CQI에 어떤 차이를 만드는지에 초점을 맞춥니다.

Several studies have contributed to a better definition of the quality culture concept20,21 and have identified subcultures within higher education.22,23 Moreover, previous research has contributed to the insight that the success of quality management can be explained by its alignment with cultural factors and faculty preferences.24,25 Yet most studies on quality culture are of a theoretical, descriptive nature.19 There is a lack of empirical research on the way students and faculty involved in quality policies and procedures conceptualize a quality culture. Specifically, an enhanced insight across institutions is needed in how work-related psychological attitudes counterbalance quality control and accountability procedures. Increased knowledge in this area will support the merit of nurturing a quality culture. Our study addresses the questions what are the key features of an organizational quality culture and how do these features contribute to continuous improvement of undergraduate medical education? As systems and processes for CQI in medical schools are increasingly becoming alike, we mainly focus on how work-related psychological attitudes and organizational value orientations make a difference in CQI.

방법

Method

연구 설계

Study design

우리는 사회 구성주의적 관점에서 다기관 포커스 그룹 연구를 수행했습니다. 연구 설계는 연역적(이론에서 실천으로) 접근법과 귀납적(실천에서 이론으로) 접근법을 결합한 것이 특징입니다.26 포커스 그룹 토론은 참가자들의 다양한 경험, 관점, 태도를 포착하는 데 도움이 되었습니다.27 데이터 수집, 분석, 해석은 순차적으로 진행되어 분석 절차를 반복적으로 조정하고 개선할 수 있었습니다.

We conducted a multicenter focus group study, operating from a social constructivist stance. The study design is characterized by combining a deductive (from theory to practice) and inductive (from practice to theory) approach.26 Focus group discussions served to capture the broad array of participants’ experiences, perspectives, and attitudes.27 Data collection, analysis, and interpretation were conducted sequentially, allowing for iterative adaptations and refinement of the analysis procedure.

설정

Setting

네덜란드의 8개 의과대학의 교육 품질 자문위원회(EC)가 이 연구에 참여하도록 의도적으로 선정되었습니다. EC 위원은 공식적으로 선출된 교수진과 학생 대표로 구성됩니다. EC의 주요 임무는 교육의 질에 영향을 미치는 모든 문제에 대한 권고 사항을 프로그램 경영진에 제공하는 것입니다. EC는 프로그램 평가가 조직되는 방식에 대해 공식적으로 동의하고 조언할 수 있는 권한을 갖습니다. 위원회는 동일한 수의 학생과 교수진으로 구성됩니다(각 EC는 8~12명의 위원으로 구성). EC를 대상으로 포커스 그룹을 실시하는 데는 네 가지 이유가 있습니다.

- 첫째, EC 교수진은 일반적으로 교육의 개발, 실행, 평가 및 개선에 대한 풍부한 경험을 가진 학자들입니다. 임상, 비임상 또는 전임상, 연구 및 교육 분야의 교수진이 참여 EC에 포함되어 있습니다.

- 둘째, EC 구성원은 현재 시행 중인 품질 시스템 및 절차에 대해 잘 알고 있으며, EC 구성원은 교육 및 평가 및 정책 부서와의 협력을 통해 이러한 시스템 및 절차에 대한 추가 지식을 습득했습니다.

- 셋째, EC에는 학생 대표가 포함됩니다. 이러한 대표성을 통해 품질과 품질 개선에 대해 교수진 외에 다른 관점을 반영할 수 있습니다.

- 넷째, 교수진과 학생의 공통된 EC 멤버십을 통한 친분은 이질적인 그룹 환경에서 열린 토론을 촉진합니다.

Education quality advisory committees (ECs) of the 8 medical schools in the Netherlands were purposively selected to participate in this research. EC members are formally elected faculty and student representatives. The central task of ECs is to provide the program management with recommendations on all matters influencing quality of education. ECs have formal rights of consent and advice on the manner in which program evaluations are organized. The committees consist of an equal number of students and faculty (each EC has 8 to 12 members). Four reasons underpin the choice to conduct focus groups among ECs.

- First, EC faculty generally are academics with ample experience in the development, implementation, evaluation, and improvement of education. Faculty with clinical, nonclinical or preclinical, research, and education backgrounds are represented in the participating ECs.

- Second, EC members are familiar with the quality systems and procedures in place; EC members have derived additional knowledge on these systems and procedures through training and cooperation with evaluation and policy departments.

- Third, ECs include student representatives. This representation allows for the incorporation of a different perspective on quality and quality improvement (besides that of faculty).

- Fourth, the acquaintance of faculty and students through their shared EC membership facilitates open discussion in a heterogeneous group setting.

네덜란드의 각 의과대학은 학교의 역사, 연구 및 교육 실적, 학생의 다양성에 따라 다소 독특한 조직 문화를 가지고 있습니다. 또한 학교 내에서 적용되는 교육적 접근 방식도 어느 정도 다릅니다. 그러나 학교마다 적용되는 교육 조직 구조와 품질 관리 접근 방식은 비슷합니다. 모든 프로그램은 학술 의료 센터에서 제공하거나 학술 의료 센터와 긴밀히 협력하여 제공합니다. 모든 참여 학교에서는 PDCA 사이클이 CQI의 지침 구조로 사용되며, 모든 프로그램은 네덜란드 학부 의학교육 프레임워크를 준수합니다.28

Each medical school in the Netherlands has a somewhat distinct organizational culture based on its history, record in research and education, and diversity of student intake. Moreover, educational approaches applied within the schools vary to some extent. The educational organization structures and quality management approaches applied across schools are comparable, however. All programs are offered by, or in close cooperation with, academic medical centers. In all participating schools, the PDCA cycle serves as guiding structure for CQI, and all programs adhere to the Dutch Framework for Undergraduate Medical Education.28

데이터 수집

Data collection

우리는 PDCA 주기에 따라 질문이 구조화된 초기 포커스 그룹 가이드를 개발했습니다. 이 구조를 따르기로 한 것은 이 주기의 각 단계를 최적화하는 것이 CQI로 이어질 것이라는 전제하에 결정되었습니다. 이 가이드(부록 디지털 부록 1: https://links.lww.com/ACADMED/A909)는 연구자의 소속 기관의 전직 EC 위원들과 함께 파일럿 포커스 그룹 세션에서 테스트한 후 질문 순서를 수정하고 이론적 개념의 사용을 제한하는 등 조정을 거쳤습니다. 2018년 5월, 네덜란드에 있는 8개 의과대학의 EC에 모두 연락을 취했습니다. 8개 위원회 중 6개 위원회가 참여하기로 동의했습니다. 참여하지 않은 위원회는 회의 계획에 필요한 시간 투자 및 어려움, EC 구성의 변화 등을 이유로 들었습니다. 총 40명의 EC 위원(학생 18명, 교수진 22명)이 6개의 포커스 그룹에 참여했습니다(표 1 참조). 회의는 2018년 7월부터 12월까지 진행되었습니다. 모든 회의(평균 시간 79분)는 있는 그대로 기록되었고, 익명화 및 코딩된 녹취록이 참가자들에게 전송되어 승인을 받았습니다. 각 포커스 그룹을 시작할 때 참가자들에게 양질의 문화에서 가장 중요한 요소가 무엇이라고 생각하는지 적어달라고 요청했습니다. 이 활동은 사전 지식을 활성화하고 데이터 삼각 측량의 한 형태로 사용되었습니다. 포커스 그룹 회의가 끝날 무렵에는 참가자들에게 그들이 작성한 의견이 토론에 포함되었는지 물어보았습니다.

We developed an initial focus group guide, with questions structured according to the PDCA cycle. The choice to follow this structure was based on the presupposition that optimizing each step of this cycle will lead to CQI. The guide (Supplemental Digital Appendix 1 at https://links.lww.com/ACADMED/A909) was tested in a pilot focus group session with former EC members from the researchers’ home institution and thereafter adjusted; the order of questions was revised, and the use of theoretical concepts was limited. In May 2018, we approached the ECs of all 8 medical schools in the Netherlands. Six of the 8 committees agreed to participate. Reasons given for not participating were the required time investment and difficulty in planning a meeting and changes in the composition of the ECs. In total, 40 EC members (18 students and 22 faculty) participated in the 6 focus groups (see Table 1). The meetings were conducted between July and December 2018. All meetings (average duration, 79 minutes) were transcribed verbatim, and anonymized and coded transcripts were sent to participants for approval. At the start of each focus group, we asked participants to write down what they considered the most important elements of a quality culture. This exercise activated prior knowledge and was used as a form of data triangulation. At the end of the focus group meeting, we asked participants if their written comments were covered in the discussion.

데이터 분석

Data analysis

데이터 분석을 위해 단계적 주제 분석의 일종인 템플릿 분석을 사용했습니다. 템플릿 분석에서는 계층적으로 구조화된 테마로 구성된 일련의 코딩 템플릿을 개발하여 데이터에 반복적으로 적용합니다. 분석이 진행됨에 따라 테마는 지속적으로 수정됩니다.29

- 첫 번째 단계로, G.W.G.B.와 W.S.d.G.는 코딩된 2개의 트랜스크립트를 독립적으로 열어 트랜스크립트 내 및 트랜스크립트 간에 반복되는 코드를 검색합니다. 품질 문화에 관한 최근 문헌고찰에 기술된 주제가 민감성 개념으로 사용되었습니다.19

- 그 후, 두 저자는 만나서 코드를 비교하고 병합하여 주제를 식별했습니다.

- 초기 코딩 템플릿은 24개의 주제와 183개의 코드로 구성되었습니다.

- 그 후 G.W.G.B.는 나머지 기록의 분석을 바탕으로 템플릿을 반복적으로 변경했습니다. 이러한 변경 사항에는 코드의 세부 사항 추가, 병합 및 연결이 포함되었습니다.

- 이후 G.W.G.B.와 W.S.d.G.가 다시 만나 코딩 템플릿의 최종 버전(25개의 테마와 199개의 코드 포함)을 확정했습니다.

- 마지막 단계로, G.W.G.B.는 최종 버전의 템플릿을 사용하여 모든 트랜스크립트를 다시 코딩했습니다.

분석 프로세스는 Atlas-ti 8.3 소프트웨어(ATLAS.ti, GmbH, 독일 베를린)를 사용하여 지원되었습니다. 포커스 그룹이 시작될 때 수행한 서면 연습의 코딩, 녹취록 분석, 전체 연구팀과의 녹취록 토론을 통해 5가지 중요한 주제를 식별하는 데 기여했습니다.

We used template analysis, a stepwise type of thematic analysis, to analyze the data. In template analysis, a succession of coding templates consisting of hierarchically structured themes is developed and iteratively applied to the data. Themes are modified continuously as the analysis progresses.29

- As a first step, G.W.G.B. and W.S.d.G. open coded 2 transcripts independently, searching for codes that recurred within and between transcripts. Topics described in a recent literature review on quality culture served as sensitizing concepts.19

- Subsequently, these 2 authors met to compare and merge codes and identify themes.

- The initial coding template comprised 24 themes and 183 codes.

- Iterative changes to the template were then made by G.W.G.B. based on the analysis of remaining transcripts. These changes concerned further detailing, merging, and linking codes.

- Hereafter, G.W.G.B. and W.S.d.G. met again to establish the final version of the coding template (including 25 themes and 199 codes).

- As a last step, G.W.G.B. recoded all transcripts using the final version of the template.

The analysis process was supported by application of Atlas-ti 8.3 software (ATLAS.ti, GmbH, Berlin, Germany). The coding of the written exercise performed at the start of focus groups, analysis of transcripts, and discussion of transcripts with the full research team contributed to the identification of 5 overarching themes.

반사성

Reflexivity

데이터 수집 및 분석 단계에서 다양한 해석을 반영하기 위해 전체 연구팀은 여러 차례 회의를 가졌습니다. 이 회의에서는 익명화 및 코딩된 녹취록, 현장 노트, CQI에 대한 각자의 이해에 대해 논의했습니다. 모든 연구팀원은 네덜란드 마스트리흐트 대학교 보건직업교육대학의 보건, 의학 및 생명과학 학부에 소속되어 있습니다. 포커스 그룹 진행자(W.S.d.G.)는 개인 및 그룹 인터뷰 경험이 풍부한 교육 과학자입니다. 양질의 문화 개발 박사 과정 중인 또 다른 팀원은 관찰자이자 메모 작성자(G.W.G.B.)로 활동했습니다. 연구팀에는 품질 보증 경험이 있는 교육 과학자(I.H.A.P.W.), 의학교육 혁신가인 의학 생리학자(M.G.A.o.E.), 혁신적인 학습 준비에 중점을 둔 교육 과학자(D.H.J.M.D.)가 추가로 포함되었습니다. 품질 관리, 정책 결정, 의학교육 등 다양한 전문성을 바탕으로 다양한 관점을 포함할 수 있었습니다. 팀 토론을 통해 연구 결과에 대한 합의에 도달했습니다.

To reflect on diverse interpretations in the data gathering and analysis stages, the full research team held several meetings. In these meetings, we discussed the anonymized and coded transcripts, field notes, and our individual understandings of CQI. All research team members are affiliated with the Faculty of Health, Medicine and Life Sciences at the School of Health Professions Education at Maastricht University in the Netherlands. The focus group moderator (W.S.d.G.) is an educational scientist with extensive experience in interviewing individuals and groups. Another team member, who is a doctoral candidate in quality culture development, acted as observer and note taker (G.W.G.B.). The research team further included an educational scientist with experience in quality assurance (I.H.A.P.W.), a medical physiologist who is a medical education innovator (M.G.A.o.E.), and an educational scientist focusing on innovative learning arrangements (D.H.J.M.D.). Our diverse expertise (in quality management, policy making, and medical education) enabled inclusion of multiple perspectives. From team discussions, we reached a negotiated consensus on the study’s results.

윤리적 고려 사항

Ethical considerations

이 연구는 네덜란드 의학교육윤리심의위원회(NVMO ERB-1046)의 승인을 받았습니다.

The study was approved by the Dutch Association for Medical Education Ethical Review Board (NVMO ERB-1046).

연구 결과

Results

연구 결과 CQI의 질적 문화 구성 요소를 반영하는 5가지 주요 주제를 확인했습니다.

- (1) 개방적 시스템 관점 육성,

- (2) 교육 (재)설계에 이해관계자 참여,

- (3) 교육과 학습의 가치인정,

- (4) 소유권과 책임 사이의 탐색,

- (5) 통합적 리더십 구축

지원적인 커뮤니케이션 환경(조직의 리더에 의해 촉진될 수 있음)은 처음 네 가지 주제에 기여하고 그 안에 통합되어 있습니다. 다음 섹션에서는 이러한 주제와 그 특징적인 요소에 대해 논의하고(그림 1 참조), 포커스 그룹 회의(FGn)에서 도출된 학생(Sn) 및 교수진(Fn)의 발언을 인용하여 설명합니다.

We identified 5 main themes that reflect quality culture constituents to CQI:

- (1) fostering an open systems perspective,

- (2) involving stakeholders in educational (re)design,

- (3) valuing teaching and learning,

- (4) navigating between ownership and accountability, and

- (5) building on integrative leadership.

A supportive communication climate (which can be fueled by the organization’s leaders) contributes to, and is integrated within, the first 4 themes. In the following sections, we discuss the themes and their characterizing elements (see Figure 1) and illustrate them with student (Sn) and faculty (Fn) quotes derived in the focus group meetings (FGn).

조사 결과 참가자들이 양질의 문화에서 가장 중요하게 생각하는 요소에 대한 일관된 그림이 드러났습니다. 따라서 결과는 통합된 방식으로 제시됩니다(학생과 교수진의 의견을 번갈아 제시). 참가자들의 응답은 PDCA 모델에 따라 구조화된 질문과 일치했으며, 이는 교직원과 학생들이 개선을 위한 체계적인 작업 방식을 내재화했음을 의미합니다. 이러한 결과는 포커스 그룹을 시작할 때 실시한 서면 연습에서 응답자들이 체계적인 접근 방식이나 PDCA 주기의 중요성을 자주 언급한 결과로 뒷받침됩니다(보충 디지털 부록 2: https://links.lww.com/ACADMED/A910).

Our findings reveal a consistent picture on what participants considered the most important aspects of a quality culture. The results are therefore presented in an integrated manner (alternating student and faculty quotes). Participants’ responses were in line with prompts structured under the PDCA model, which implies that faculty and students have internalized a systematic way of working on improvement. This finding is supported by results from the written exercise performed at the start of the focus groups in which respondents frequently referred to the importance of systematic approaches or the PDCA cycle (Supplemental Digital Appendix 2 at https://links.lww.com/ACADMED/A910).

개방적 시스템 관점 육성

Fostering an open systems perspective

참가자들은 개방적인 분위기와 외부 지향성, 실험과 혁신의 자유가 CQI에 필수적인 요소로 꼽았습니다. 이들은 내부적 연계(과정 간)와 외부적 연계(현장의 발전 및 요구사항)에 대한 끊임없는 필요성을 표명합니다. 다음 교수진의 사례에서 알 수 있듯이 개방형 시스템 관점을 취하는 것은 다양한 수준에서 관련이 있습니다:

Participants identify a general atmosphere of openness, combined with an external orientation and freedom to experiment and innovate as essential for CQI. They express a constant need for internal alignment (between courses) and external alignment (with developments in, and requirements of, the field). As the following faculty member illustrates, taking an open systems perspective is relevant on different levels:

[코스 코디네이터는 엄밀한 의미에서 자신의 임무보다 조금 더 멀리 내다볼 필요가 있습니다. 저는 항상 이를 미시적 수준이라고 부르는데, 교육으로의 전환이 이루어지는 곳입니다. 하지만 중급 수준도 있습니다. 프로그램 내에서 무엇이 선행되고 무엇이 뒤따르는지를 고려해야 합니다. 수평적, 수직적 연결이 어떻게 이루어지고 있는지, 거시적 수준에서는 프로그램에서 사회적 맥락과 전문성에 대한 수요, 대학원 교육과의 연계까지....... 이렇게 복잡한 상황에서 교육을 발전시켜야 한다는 것이죠. 이것이 바로 도전입니다. (FG1, F5)

[Course coordinators] need to look a bit further than just their assignment in the strict sense. I always call that the microlevel, where the translation to education is being made. But then, there’s also the mesolevel. Within the program, you should consider what precedes and what comes after. How the horizontal and vertical connections are made, and at the macrolevel, from the program to the societal context and the demand for specialisms, the alignment with postgraduate training…. That you have to develop education in such a complicated situation. That is the challenge. (FG1, F5)

참가자들은 조직의 적응력에 중요한 기여 요인으로 개방성과 외부 지향성을 언급합니다. 프로그램 환경 내부 또는 외부에서 얻은 새로운 인사이트는 CQI의 변화 동인으로 간주됩니다. 인증 패널의 권고, 의료계의 다른 프로그램과의 벤치마킹, 노동 시장의 의견, 교육자, 동료 및 학생의 조언 등을 통해 얻은 새로운 인사이트가 그 예입니다. 이러한 인사이트를 실행에 옮기려면 유연성, 창의성, 실험과 혁신의 여지가 필요합니다:

Participants refer to openness and an external orientation as important contributors to the organization’s adaptivity. New insights obtained from within or outside the program environment are seen as drivers of change for CQI. Examples are new insights derived through recommendations by accreditation panels; benchmarking with other programs in medicine; inputs from the labor market; and advice from educationalists, peers, and students. To translate these insights into practice, flexibility, creativity, and room to experiment and innovate are needed:

실수를 해도 괜찮고 실수에 대해 솔직하게 말할 수 있는 문화가 조성되어야 합니다. 모든 것이 완벽하게 이루어지기를 서로에게 요구한다면 이를 억제해야 합니다....... 또한 ... 교육 자료가 완전히 고정되어 있지 않고 약간 유연한 형식으로되어있어 모든 사람이 자신의 길을 찾을 수 있습니다. 이렇게 하면 사람들이 더 많이 참여하고 다양한 접근 방식이 어떻게 작동하는지에 대한 정보를 수집할 수 있습니다. (FG1, F2)

The related culture is that it is all right to make mistakes and that you can be open about it. If we demand from each other that everything goes perfect, then you suppress that…. Also … that the educational material is not completely set in stone, but has a bit of a flexible format, so that everyone can find their way in it. That way, people thrive and you can collect information on how different approaches work. (FG1, F2)

교수진이 교육 접근 방식을 과감하게 바꾸는 것이 중요합니다. 예를 들어, 강의가 그 자체로 효과적이지 않다는 말은 종종 있습니다. 그러나 우리는 여전히 강의가 일반적인 관행인 상황에 처해 있습니다. (FG3, S1)

It is important that faculty dares to change educational approaches. For instance, it has often been said that lectures are not per se effective. However, we are still in a situation in which lectures are common practice. (FG3, S1)

학생과 교수진은 특히 커리큘럼 내용의 일관성을 유지하기 위해 교수팀 내, 교수 코디네이터 간의 소통에 주의를 기울여야 한다고 지적합니다.

Students and faculty point out that communication within teaching teams and between teaching coordinators requires attention, especially to safeguard alignment of the curriculum content.

교육 (재)설계에 이해관계자 참여하기

Involving stakeholders in educational (re)design

EC 위원들은 교육을 (재)설계할 때 교수진과 학생의 참여와 공동의 목표 지향성에 주목해야 한다고 설명합니다. 이러한 참여는 다양한 시나리오, 기회, 과제를 고려하는 데 기여합니다:

The EC members elaborate that involvement and a shared goal orientation of faculty and students in the (re)design of education require attention. This involvement contributes to considering various scenarios, opportunities, and challenges:

모든 사람은 그것[교육 발전]에 대해 다른 관점을 가지고 있으며, 모든 사람이 다른 가능성이나 구현을 봅니다. 예를 들어, 일이 잘못될 수도 있습니다. 서류상으로는 훌륭해 보이지만 학생과 교수진이 경험하는 것은 완전히 다를 수 있습니다. 그렇기 때문에 모든 사람의 참여가 필요하다고 생각합니다. (FG5, S2)

Everyone has a different view on it [development of education], and everyone sees different possibilities or implementations. Also, for example, where things can go wrong. Something can look great on paper but can be experienced totally different by students and faculty. That is why I think we need everyone on board. (FG5, S2)

응답자들은 또한 기대치를 명확히 하고 불확실성을 제거하여 교육 변화 활동에 대한 지원을 창출하기 위해서는 교직원과 학생의 참여가 중요하다고 언급합니다. 그러나 실제로는 더 큰 규모의 커뮤니티를 참여시키고 소통하는 목표를 달성하기가 어려울 수 있습니다:

Respondents further note that involvement of faculty and students is important to clarify expectations, take away uncertainty, and therewith create support for educational change activities. However, in practice, the objective to involve—and communicate with—the larger community can be difficult to meet:

계획 개발의 전체 기간 동안 우리는 계획을 실행해야 하는 사람들을 충분히 참여시키지 못했습니다. 이들에게 충분히 알리지 않았고, 갑자기 이런 일이 발생하니 압박감이 컸습니다. 반드시 필요한 일이었습니다. 사람들이 우리가 왜 이런 일을 하는지 충분히 알지 못했습니다. 이유가 무엇이었는지요. (FG6, F6)

During the whole period of plan development, we insufficiently involved the people who eventually needed to implement it. We did not inform them sufficiently and what happens all of a sudden, the pressure was on. It needed to happen. Without people being fully aware of why we were doing this. What the reason was. (FG6, F6)

상향식 개선 접근 방식과 하향식 개선 접근 방식 사이의 균형이 자주 언급됩니다. 한편으로는 기본 틀과 (재)개발 구조를 제공하기 위해 조직 고위층에서 시작된 접근 방식이 필요하고, 다른 한편으로는 교수진과 학생들이 계획에 기여할 수 있는 능력이 중요합니다:

The balance between bottom-up and top-down improvement approaches is often referred to. On the one hand, approaches initiated at a high level in the organization are needed to provide a basic framework and (re)development structure, while on the other hand, the ability of faculty and students to contribute to plans is important:

하향식도 상향식도 아닌, 모든 이해 당사자들과 협의하여 문제를 파악하고 그런 방식으로 합의에 도달할 수 있어야 한다는 것이죠. 적어도 그것이 철학입니다. 코디네이터나 교수가 커리큘럼을 설계하고 "이렇게 하세요."라는 식으로 실행하는 것이 아니라 말이죠. (FG5, S3)

That it is neither a top-down nor a bottom-up implementation, but that we identify issues in consultation with all parties involved, and that a consensus can be reached that way. At least, that is the philosophy. Instead of a coordinator or professor designing a curriculum and implementing it like “here you go.” (FG5, S3)

구체적인 가치는 대표 기관에 귀속됩니다. 이러한 기구들은 새로운 아이디어를 발굴하고 모범 사례에 대한 통찰과 공유를 바탕으로 조언을 제공함으로써 개선에 기여합니다:

Specific value is attributed to representative bodies. These bodies contribute to improvement by identifying new ideas and providing advice based on insights in—and sharing of—best practices:

저는 학생들이 교육 분야의 강점과 모범 사례를 잘 파악하고 있다고 생각합니다..... 제 생각에 학생[대표]으로서 우리가 해결해야 할 과제 중 하나는 이러한 품질 측면이 실제로 무엇인지 인식하고 "이것이 아이디어였고, 이것이 구현되는 방식이며, 품질을 개선하기 위해 주목해야 할 지점"을 고려하는 것입니다. (FG3, S1)

I believe that students are very well equipped to map the strong aspects and best practices within education…. In my opinion, part of the challenge for us as students [representatives] is to be aware of what those quality aspects actually are … to consider “this was the idea, this is how it is implemented, and these are the points of attention to improve quality.” (FG3, S1)

응답자들은 이해관계자의 참여를 보장하기 위해 변화 리더에게 프로젝트 관리 및 커뮤니케이션 기술이 필요하다고 지적합니다. 의학교육 환경에서 이러한 기술에 대한 관심이 부족하기 때문에 참여가 부족한 것으로 나타났습니다.

The respondents indicate that to safeguard stakeholder involvement, change leaders require project management and communication skills. A lack of attention for such skills in the medical education setting is expressed as reason for experiencing a shortfall of involvement.

교육과 학습의 가치

Valuing teaching and learning

교육을 개선하려는 교수진의 동기는 학생을 향한 (학문적, 직업적) 발전에 대한 헌신에서 비롯됩니다. 예를 들어, 교수진은 교육 활동 후 학생들과의 만남을 통해 동기 부여 효과를 얻을 수 있으며, 이 시간 동안 학생들은 특정 활동의 학습 효과에 대해 감사를 표합니다. 학생들에 따르면 교수진의 헌신은 여러 가지 방식으로 나타납니다(예: 가시성 및 접근성, 학생 질문에 대한 응답, 강의에 대한 열정). 헌신적인 교수진은 자기 성찰적인 태도를 취하는 경향이 더 강하고 피드백에 더 잘 반응하며, 이는 내부적인 개선 의지에서 비롯됩니다:

The motivation of faculty to improve education stems, to an important degree, from commitment to the (academic and professional) development of students. Faculty, for example, point to the motivating effect of meeting with students after teaching activities, during which time students express appreciation for the learning effect of certain activities. According to students, faculty’s commitment manifests in several ways (e.g., through visibility and approachability, responsiveness to student questions, enthusiasm in lecturing). Committed faculty are more inclined to attain a self-reflective attitude and are more responsive to feedback, stemming from an internal drive to improve:

네, 우선은 개선하려는 교사의 의지가 중요하다고 생각합니다. 이것은 매우 다양한 개선 계획을 통해 얻을 수 있는 것이기도 합니다: 한 교사는 다른 교사보다 비판에 훨씬 더 개방적입니다. (FG2, S2)

Yes, I believe for one thing, it involves the willingness of the teacher to improve. This is also what you get from many very different improvement plans: One teacher is far more open to criticism than the other. (FG2, S2)

교사와 학생 모두 의사 결정 과정에 참여하고 목표를 공유하는 것이 헌신에 기여한다고 보고합니다. 일반적으로 교육에 대한 관심과 인정은 교사의 가르침에 대한 동기를 부여합니다. 다음 교직원의 말은 교육보다 연구를 중시하는 것이 교육에 투자하려는 노력을 방해할 수 있음을 보여줍니다:

Both teachers and students report that their participation in decision-making processes and shared goal formulation contribute to commitment. In general, attention to and appreciation of education fuel faculty’s motivation to teach. The following quote from a staff member illustrates that valuing research over education can hamper efforts to invest in education:

학과장은 교수진의 연구와 논문을 작성하는 것에 훨씬 더 많은 관심을 보입니다. 블렌디드 러닝을 구현하거나 새로운 학습 프로그램 청사진을 만들면 그것도 성과가 되지만, 부서장을 행복하게 하는 성과는 아닙니다. (FG5, F2)

A head of department is far more interested in faculty members’ research and you producing manuscripts. That is something which pays off … if you implement blended learning or create a new study program blueprint … that’s also output, but it’s not the kind of output that makes the department head happier. (FG5, F2)

6개 기관의 응답자 모두 과도한 업무량이 교육에 전념하는 데 방해가 된다고 답했습니다. 이에 반해 상급 경영진의 교육에 대한 관심과 인정은 헌신을 자극합니다:

Respondents from all 6 institutions report that excessive workload hinders the commitment to education. As a counterbalance, attention to—and appreciation of—education from upper management stimulates commitment:

교육에 대한 관심과 열의에 따라 교육의 질이 만들어지기도 하고 깨지기도 하는데, 교육은 하다 보면 좋아지기 시작하고 자동적으로 향상되기 때문입니다. 그래서 주로 시간과 관심, 주변 사람들의 관심이 중요하다고 생각합니다. 그래서 네, 교육 경력 경로와 연례 평가에서 상사의 관심... 그런 모든 종류의... 교육에 대한 조직 내 관심. (FG3, F2)

The quality of education is made or broken by the attention to and enthusiasm for education, because if you do it, you will start to like it, and you will also automatically improve. So I think it mostly concerns time and attention and interest from other people. So yes, educational career paths and your superior’s attention during the annual appraisal … all that kind of … attention within the organization for education. (FG3, F2)

교수진은 헌신적인 교직원들이 동료 교사와의 대화나 비공식적으로 학생의 의견을 묻는 등 (표준 교육 평가 외에) 추가적인 피드백을 적극적으로 구한다고 설명합니다. 학생 대표들은 교수와 학생 간의 짧은 거리와 학생이 비공식적으로 피드백을 제공할 수 있는 기회가 이러한 측면에서 매우 중요하다고 덧붙였습니다. 참가자들은 교직원-학생 커뮤니티 구축을 통해 교수와 학습을 중시하는 것이 중요하며, 이는 대면 상호작용의 여지가 많은 소규모 단위의 교육을 통해 달성할 수 있다고 지적합니다.

Faculty explain that committed staff members actively seek additional sources of feedback (other than the available standard educational evaluations), for instance, by sparring with peers and by informally asking for student opinions. The student representatives add that a short faculty–student distance and student opportunities to provide feedback informally are instrumental in this respect. Participants point to the importance of valuing teaching and learning through staff–student community building, which can be reached through teaching in smaller units with more room for face-to-face interaction, for example.

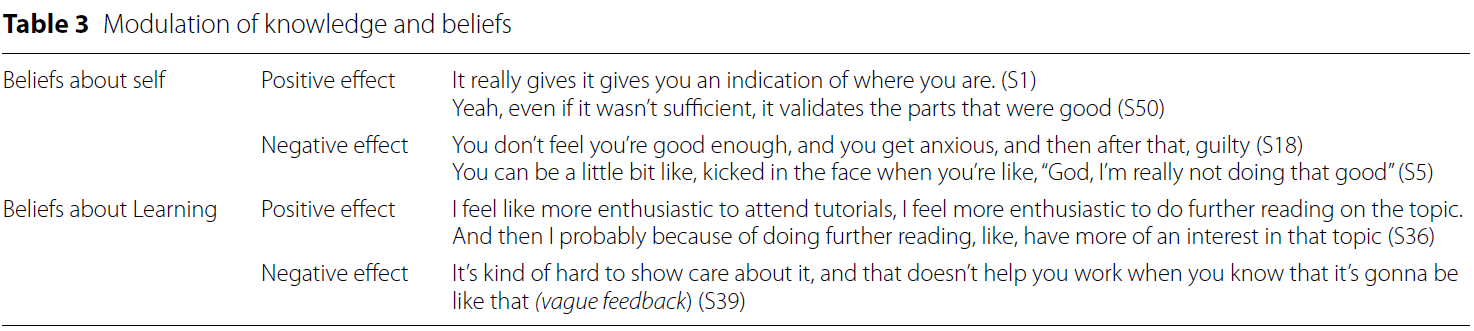

소유권과 책임 사이에서 탐색하기

Navigating between ownership and accountability

교수진에 따르면, 자신의 통찰력을 바탕으로 교수 학습 활동을 설계하면 주인의식을 고취하고 지속적으로 개선하려는 동기를 강화할 수 있다고 합니다. 교육 (재)개발을 (팀) 공동의 과제로 삼고 전문가적 자율성의 여지를 두면 팀이 헌신한다면 교육의 질에 영향을 미칩니다:

According to faculty, designing teaching and learning activities based on their own insights stimulates ownership and reinforces their motivation to continuously improve. Making the (re)development of education a shared (team) task, with room for professional autonomy, affects educational quality, provided that the team is committed:

최고의 기획 그룹은 광범위한 토론이 이루어지고 토론을 피하지 않는 팀입니다..... 헌신과 함께한다는 느낌이 있어야 합니다. "우리는 무언가를 창조할 것이다." "우리는 무언가를 만들 것이다." 이것이 바로 퀄리티를 얻는 방법입니다. 때때로 관리 기관에서 정한 경계를 넘을 수도 있습니다. 하지만 그런 경우에도 그들은 어쨌든 당신에게 호루라기를 불 것입니다. (FG1, F4)

The best planning groups are teams in which extensive discussions take place, and where discussion is not avoided…. There has to be commitment and a feeling of togetherness. “We are going to create something.” “We are going to build something.” That is how you get quality. Maybe you will sometimes cross the boundaries set by the management institute. But yes, in that case, they will blow the whistle on you anyway. (FG1, F4)

자율성과 주인의식은 동료 지원 및 책무성 절차(즉, 체계적인 평가 및 개선 접근 방식으로서의 PDCA 주기)와 연계되어야 합니다. 결과 평가보다 단기적인 학생 만족도와 과정에 중점을 두는 것은 교수진이 선호하는 학생의 종단적 발달에 초점을 맞추는 것과 모순됩니다. 또한 평가가 혁신과 연계되지 않거나 학습 효과를 포착하지 못할 수도 있습니다:

Autonomy and ownership need to be linked with peer support and accountability procedures (i.e., the PDCA cycle as systematic evaluation and improvement approach). An emphasis on short-term student satisfaction and process over outcome evaluations contradicts faculty’s preferred focus on the longitudinal development of students. Moreover, evaluations might not be aligned to innovations or fail to capture learning effects:

목표에 도달했는지 훨씬 더 광범위하게 측정해야 하고, 그러면 다시 제 목표로 돌아와야 합니다. 제 목표는 시험이 끝나거나 학기가 끝난 후 학생들이 행복해하는 모습을 보는 것이 아닙니다. 제 목표는 학생들이 훌륭한 의사가 되는 것을 보는 것입니다. 그것이 제 목표입니다. (FG6, F5)

You need to measure to a much larger extent if you reached your goals, and then I come back to my goal again. My goal is not to see happy students after their exam or after the semester. My goal is to see them become a great doctor. That is my goal. (FG6, F5)

학생과 교수진은 피드백이 건설적인 것이 중요하다고 말합니다. 여기서 응답자들은 내러티브 피드백의 부가가치에 대해 구체적으로 언급합니다. 평가의 후속 조치에 대한 정보와 커뮤니케이션이 부족하면 피드백의 질이 떨어집니다. 평가의 목적과 후속 조치에 대한 추가 설명은 학생이 양질의 피드백을 제공할 가능성을 높일 수 있습니다. 또한 명확한 책임 구조를 포함시키는 것이 중요합니다:

Students and faculty report that it is key for feedback to be constructive. Herein, respondents refer specifically to the added value of narrative feedback. A lack of information and communication on the follow-up of evaluations mitigates feedback quality. Further explanation of the purposes and follow-up of evaluations can enhance the likeliness of students’ provision of high-quality feedback. Moreover, embedding clear responsibility structures is key:

저희는 1년 넘게 무슨 일이 일어나고 있는지 알아내려고 노력해 왔습니다. "저 사람은 이렇게 하고, 저 사람은 저렇게 하고, 저 사람은 저렇게 피드백을 준다"라고 말할 수 있는 사람은 아무도 없습니다. 코스를 보면 개선하는 것이 번거롭고 몇 년이 걸립니다. 하지만 어떤 방식으로 구조화되어 있고 누가 무엇을 책임지는지 위에서부터 아래로 명확해야 한다고 생각합니다. (FG4, S1)

We have been trying to find out what is going on for more than a year now. There is nobody who can tell us “that person does this, that one does that, and that one gives feedback,” etc. If you look at a course, it is cumbersome to improve and it will take years. But I think it should be clear from the top down that it is structured in a certain way and who is responsible for what. (FG4, S1)

복잡한 조직 구조와 많은 교직원이 조정 및 실행 역할에 관여하는 것은 평가 결과에 대한 후속 조치를 어렵게 하는 요인으로 꼽힙니다.

Complex organizational structures and involvement of many faculty members in coordination and implementation roles are considered to frustrate the follow-up on evaluation results.

통합적 리더십 구축

Building on integrative leadership

도표 1은 통합적 리더십이 앞서 설명한 4가지 주제에 존재하는 긴장을 엮어내는 데 어떻게 기여하는지를 요약한 것입니다. 개방적 시스템 관점을 키우는 것과 관련하여 학생을 포함한 다학제적 팀을 구성하는 것이 중요한 것으로 간주됩니다. 이러한 팀을 구성하면 책임과 의사결정을 공유하고 다양한 관점을 포용할 수 있습니다:

Chart 1 summarizes how integrative leadership contributes to intertwining the tensions present within the 4 themes described previously. With regard to fostering an open systems perspective, the formation of multidisciplinary teams (including students) is considered important. Such teams allow for shared responsibilities, decision making, and the inclusion of different perspectives:

작업을 수행해야 하는 그룹부터 시작해야 한다고 생각합니다. 그룹은 너무 크지 않고 가능한 한 이질적이어야 하며, 교육 조직 내 모든 구성원으로부터 해당 과제를 수행하도록 승인을 받아야 합니다. (FG3, S1)

I think you should start with the group that has to perform the task. The group should not be too large, but as heterogeneous as possible … and it should get approval from everyone within the educational organization to perform that task. (FG3, S1)

리더는 중요한 (프로그램 또는 조직) 목표와 개별 교수진의 야망, 동기 부여 및 전문성 사이의 연결 고리를 자극해야 합니다. 팀이나 개별 교사에게 너무 많은 자유를 제공하면 커리큘럼의 일관성을 해칠 수 있습니다:

Leaders ought to stimulate connective links between the overarching (program or organization) goals and individual faculty members’ ambitions, motivations, and specialties. Offering too much freedom to teams or individual teachers can endanger the curriculum coherence:

현재 많은 교사들이 [학습 프로그램 관리자가] 내용을 무시하고 자기 방식대로 교육을 개발하는 것을 볼 수 있습니다. 물론 좋은 의도로 하는 일이라는 점을 분명히 말씀드리지만, 그렇게 되면 모든 것이 뒤죽박죽이 되죠. (FG4, F2)

What you see now is that when those people [the study program management] ignore the content, a lot of teachers develop education in their own way. Of course they do this with the best intentions, let me make that clear, but yeah, then everything becomes all jumbled. (FG4, F2)

팀이 자유롭게 운영할 수 있는 일반적인 프레임워크는 혁신을 위한 유연성과 효과와 효율성을 유지하기 위한 안정성 사이에서 균형을 잡는 데 도움이 됩니다:

A general framework within which teams have freedom to operate helps to establish a balance between flexibility to innovate and stability to remain effective and efficient:

예, 의도된 목표에 따라 프레임워크가 결정되고, 결국 프레임워크에 따라 사람들에게 "여러분에게는 레버리지와 일정한 자유가 있지만, 주어진 프레임워크의 경계 내에서만 가능합니다."라고 말할 수 있습니다. (FG6, F5)

Yes, the intended aims determine the framework and the framework in the end determines that you tell people, “You have leverage and a certain freedom, but within the boundaries of the provided framework.” (FG6, F5)

지지적인 커뮤니케이션 분위기를 조성하는 리더의 능력은 개선 이니셔티브의 성공을 결정하는 중요한 요소로 간주됩니다. 리더는 커뮤니케이션 프로세스를 통해 조직 변화의 비전에 대한 투명성을 높이고 참여를 촉진할 수 있습니다:

Abilities of leaders to establish a supportive communication climate are considered important determinants of the success of improvement initiatives. Through communication processes, leaders can foster transparency on the vision behind organizational change and foster involvement:

좋은 비전일지라도 그 비전이 정확히 무엇을 수반하는지 알고 싶을 수 있습니다. 비전을 공유하면 오류가 발생할 여지가 있습니다. 그러면 적어도 지평선에 있는 점이 무엇인지 알 수 있습니다. 누군가 이메일을 보내는 것을 잊어버려도 "괜찮아. 우리가 무엇을 위해 노력하고 있는지 알아요. 왜 이런 일이 지금 일어나야 하는지 알아요."라고 생각할 수 있습니다. (FG2, F2)

It could just happen to be a good vision, but then you would like to know what it entails exactly. If you share it, this vision, you have some room for errors. Then at least you know what the dot on the horizon is. It could happen that somebody forgets to send you an email, and you think, “It’s okay. I know what we are working towards. I know why this needs to happen now.” (FG2, F2)

EC 멤버들은 지원과 협력적인 교사 네트워크, 교육 커리어 트랙 구축, 교육에 대한 추가 시간 또는 보상 제공 등 리더가 교수와 학습의 가치를 증진하고 동기를 유발하는 다양한 사례를 제시합니다. 리더는 교육에 대한 인식과 건설적인 피드백 제공을 통해 소유권(및 자율성)과 책임(및 통제)의 균형을 맞추는 데 영향을 미칩니다.

The EC members provide various examples of the way leaders promote valuing of teaching and learning and trigger motivation: through support and collaborative teacher networks, establishing education career tracks, and offering additional time or reimbursement for teaching. Leaders affect the balance of ownership (and autonomy) with accountability (and control) through appreciation of education and the provision of constructive feedback.

토론

Discussion

이 연구에서 우리는 의학교육에서 CQI 문화를 형성하는 5가지 주제를 확인했습니다. 차트 1에서 볼 수 있듯이, 조직 내에는 교육의 질을 유지하고 발전시키기 위한 방향성 사이에 다양한 긴장이 존재합니다. 이러한 경쟁적 지향점 간의 통합과 시너지 창출을 위해서는 다학제적 협업, 개방적 의사소통, 교수진 개발 및 인적 자원에 대한 투자, 품질 관리보다 품질 향상에 초점을 맞춘 책임 절차가 강화되어야 합니다.

In this study, we identified 5 themes that in concert shape a culture for CQI in medical education. As Chart 1 illustrates, various tensions within organizations exist between orientations to maintain and further develop the quality of education. The integration and creation of a synergy between these competing orientations call for increased multidisciplinary collaboration, open communication, investments in faculty development and human resources, and accountability procedures focusing on quality enhancement over quality control.

개방형 시스템 관점(주제 1)은 지식 공유 강화와 창의성 및 혁신의 자극을 통해 질적 발전을 촉진하는 데 도움이 됩니다. 이러한 관점을 취하면 학교가 점진적 단일 루프 학습과 유사한 CQI 노력에 전념하는 것에서 진정한 학습 조직(수정된 목표, 의사결정 규칙 또는 양쪽 모두의 이중 루프 학습과 유사한)으로 전환하는 데 도움이 됩니다.30 CQI 문화를 촉진하려면 의과대학의 현재 가치관을 변화시킬 필요가 분명합니다. 교수진은 일반적으로 유연하고 인간 중심적인 조직을 선호하지만,31,32 의과대학은 여전히 보수적이고, 위계적이며, 단절되고, 인본주의적 성향을 저해하는 것으로 인식되는 경우가 많습니다.22,33-35

An open systems perspective (Theme 1) aids in promoting quality development through intensified knowledge sharing and the stimulation of creativity and innovation. Taking such a perspective aids schools in their shift from devoting to CQI efforts (resembling incremental, single-loop learning) to becoming true learning organizations (resembling modified goals, decision-making rules, or both—double-loop learning).30 To stimulate a culture for CQI, a need for change in current values of medical schools is apparent. Whereas faculty typically prefer a flexible and human centered organization,31,32 medical schools are still often seen as conservative, hierarchical, disconnected, and discouraging humanistic orientations.22,33–35

광범위한 이해관계자의 참여(주제 2)는 지식, 기술 및 (잠재적으로 경쟁적인) 가치의 다양성이 교육의 질에 대한 다면적인 개념을 다루는 데 도움이 되므로 CQI의 핵심입니다.36 그러나 의료 전문가와 학계는 (임상 서비스 활동, 부서, 학문 분야 등과 관련된) 사일로 내에서 일하고 학습하는 데 익숙하며, 이는 고유한 태도, 문제 해결 능력 및 공통 언어 사용을 강화합니다.37 또한 의사와 연구자는 일반적으로 상당한 자율성을 가지고 있습니다. 이들은 개별적인 책임을 지는 데 익숙하고 자신의 학문 분야의 이익을 옹호하는 데 열심입니다.37 다양한 배경을 가진 교수진이 참여하는 철저한 토론과 공동 창작 세션은 집단적 개선 활동을 시작하는 데 핵심적인 역할을 합니다.38 또한 CQI는 학생을 고객 또는 소비자에서 조직 문화의 적극적인 구성원 및 기여자로의 역할 변화를 수반합니다.

Broad stakeholder involvement (Theme 2) is key to CQI, as diversity in knowledge, skills, and (potentially competing) values helps to address the multifaceted notion of education quality.36 However, medical professionals and academics are used to working and learning within silos (relating to their clinical service activities, departments, disciplines, etc.), which reinforce distinct attitudes, problem-solving skills, and the use of a common language.37 Moreover, physicians and researchers typically have a large degree of autonomy. They are used to taking individual responsibility and are keen to defend interests of their own discipline.37 Thorough discussions and cocreation sessions involving faculty from different backgrounds form a keystone to initiate collective improvement activities.38 Additionally, CQI entails a role change from students as clients or consumers to active members of and contributors to the organizational culture.

인센티브와 교수진의 요구 만족도에 대한 연구와 함께,39,40 우리는 CQI의 외재적 동기에 대한 몇 가지 예시를 발견했습니다. 자금 지원, 개발 시간, 정보 공유, 교수진 개발 이니셔티브 증가를 통한 교육 및 학습의 가치인정(주제 3)은 조직의 개선 잠재력에 영향을 미칩니다.41,42 따라서 조치를 취하는 데 필요한 자원이 부족하다면 단순히 주인의식과 책임감을 고취하는 것(주제 4)은 유익한 결과로 이어지지 않을 것입니다.

In line with research on incentives and faculty needs satisfaction,39,40 we found several illustrations of extrinsic motivators for CQI. The valuing of teaching and learning (Theme 3) through increased funding, time for development, information sharing, and faculty development initiatives influence the organization’s improvement potential.41,42 Hence, a mere promotion of ownership and accountability (Theme 4) will not lead to beneficial results if required resources to take action are lacking.

우리의 연구 결과는 통합적 리더십(주제 5)이 양질의 문화 발전을 지원한다는 것을 보여줍니다. 의학교육의 리더십은 개별 교수진의 감독, 지도, 지원에서 더 넓은 집단에 초점을 맞추는 것으로 변화하고 있습니다. 리더는 강력한 리더십에 CQI의 책임을 돌리는 대신 동기부여자, 멘토, 촉진자 역할을 해야 합니다. 지식 집약적인 의과대학 환경에서 리더와 직원들은 조직의 문제에 대한 의미와 해결책을 재구성합니다.43 의학교육의 CQI는 다양한 스타일을 결합할 수 있고 다양한 이해관계자의 목표와 야망을 통합할 수 있는 리더가 가장 잘 수행할 수 있습니다.44

Our findings indicate that integrative leadership (Theme 5) supports further quality culture development. Leadership in medical education is changing from individual faculty supervision, guidance, and support to a focus on the broader collective. Instead of attributing responsibility for CQI to strong leadership, leaders are expected to be motivators, mentors, and facilitators. In the knowledge-intensive setting of medical schools, leaders and employees coconstruct meaning and solutions to organizational issues.43 CQI of medical education is best served with leaders who are able to combine multiple styles and who are able to coalesce different stakeholder goals and ambitions.44

실천 커뮤니티(CoP)45를 구현하면 지속적인 개선을 위한 문화 주제를 다룰 수 있는 기회의 창이 열립니다. CoP는 다양한 학문적 배경을 가진 교사들 간의 상호작용을 촉진하고 새로운 관점을 얻을 수 있는 기회를 창출합니다. 또한 이러한 커뮤니티 내에서 조직된 (연수) 활동은 참여 의식을 강화하고 역량, 자신감, 신뢰성, 유대감을 향상시킵니다.46 CoP는 교수 학습, 개인 개발, 교사 정체성 확립을 중시하는 환경을 형성합니다. 교육 및 학습 커뮤니티의 건설적인 동료 피드백 프로세스는 교육 개선에 대한 주인의식과 책임감의 균형을 맞추는 데 도움이 됩니다. CoP의 개방적이고 종적인 성격은 그 부가가치에 필수적이며, 단순히 우수한 챔피언들의 일시적인 리그를 구축하는 것을 넘어서야 한다는 점에 유의해야 합니다.

The implementation of communities of practice (CoPs)45 opens a window of opportunity to address the themes of a culture for continuous improvement. CoPs facilitate interaction between teachers from diverse disciplinary backgrounds and create opportunities to gain new perspectives. Moreover, (training) activities organized within these communities strengthen a sense of involvement and enhance competence, confidence, credibility, and connection.46 CoPs form an environment in which the valuing of teaching and learning, personal development, and teacher identity building is central. Constructive peer feedback processes in teaching and learning communities help to balance ownership and accountability for educational improvement. It should be noted that an open and longitudinal character of CoPs is essential to their added value; they should go beyond the mere establishment of a temporal league of quality champions.

이론적 및 실무적 의의

Theoretical and practical significance

본 연구는 표준 품질 관리 접근 방식이 품질 문화 개념에서 도출된 통찰력으로 보완되어야 한다는 교수진과 학생들의 의견을 대변합니다. 보고된 결과는 이 이론적 개념에 대한 더 깊은 통찰력을 얻는 데 기여했습니다. 우리의 연구 결과는 책무성을 강조하는 정적인 접근 방식에서 전문가의 자율성과 커뮤니티 구축의 여지가 있는 유연한 접근 방식으로의 전환을 시사합니다. CQI는 교육의 가치, 교수진의 동기 부여, 학생의 개인적, 학업적, 전문적 개발에 더욱 집중할 것을 요구합니다.

The present study gives voice to the opinion of faculty and students that standard quality management approaches should be complemented by insights derived from the quality culture concept. The reported results have contributed to gaining a deeper insight into this theoretical notion. Our findings imply a shift from static approaches emphasizing accountability toward flexible approaches with room for professional autonomy and community building. CQI requires a stronger focus on the valuing of teaching; faculty motivation; and student personal, academic, and professional development.

강점과 한계

Strengths and limitations

이 연구는 질적 문화를 경험적으로 연구한 몇 안 되는 연구 중 하나이기 때문에 이용 가능한 문헌에 기여합니다. 여러 기관에서 데이터를 수집하고 교수진과 학생의 관점을 모두 고려했습니다. 연구 결과에 따르면 의과대학 내 가치 지향성이 품질 관리 접근 방식과 교수진의 업무 관련 심리적 태도가 상호 작용하는 방식을 설명하는 데 매우 관련이 있는 것으로 나타났습니다. 참여 의과대학에서는 이러한 지향점이 다소 동질적이었지만, 다른 상황에서는 다를 수 있습니다. 네덜란드 의과대학(8개 중 6개)만 조사 대상에 포함되었다는 점도 결과의 해석과 적용 가능성에 있어 고려해야 할 사항입니다. 또 다른 한계는 EC 위원들의 견해가 다른 중요한 이해관계자들과 다를 수 있다는 점입니다. 그러나 EC는 일반적으로 조직 중간 수준에서 운영되기 때문에 경영진과 풀뿌리 관점을 모두 파악했다고 가정합니다. 세 번째 (잠재적) 한계는 응답자들이 익명성이 보장되었음에도 불구하고 다른 대학에 소속된 연구자들과 특정 경험을 공유하는 것을 꺼렸을 수 있다는 점입니다.

This study contributes to the available literature as it is one of few studies that research quality culture empirically. We gathered data from multiple institutions and took into account both faculty and student perspectives. The findings suggest that value orientations within medical schools are highly relevant in explaining how quality management approaches and work-related psychological attitudes of faculty interact. Whereas these orientations were rather homogeneous in the participating medical schools, they might vary in other contexts. The fact that we included only medical schools from the Netherlands (6 of 8) should be taken into account in the interpretation and transferability of results. A further limitation is that views of EC members might differ from other important stakeholders. However, as ECs typically operate on the organizational mesolevel, we assume to have captured both management and grassroots perspectives. A third (potential) limitation is that the respondents, despite guaranteed anonymity, might have been reluctant to share particular experiences with researchers affiliated with another university.

향후 연구를 위한 제언

Recommendations for future research

CQI의 새로운 길을 개척하기 위해서는 개별적인 교육 개선 접근 방식을 집단적인 노력으로 전환하는 개입에 대한 향후 연구가 특히 유용할 것입니다. 또한 이 연구에서 확인된 5가지 주제와 관련된 모범 사례에 대한 사례 연구는 CQI를 위한 조직의 변화와 개발을 시작하는 데 지렛대가 될 것입니다.

To pave new paths for CQI, future research on interventions that convert individual educational improvement approaches to collective endeavors would be particularly valuable. In addition, case studies on best practices relating to the 5 themes identified in this study would provide levers to initiate organizational change and development for CQI.

결론

Conclusions

의과대학의 3대 사명인 교육, 연구, 임상 서비스 중 교육은 전통이 지배적이기 때문에 질적 개선과 변화가 필요하다는 인식이 가장 느린 경우가 많습니다. 의과대학에서 양질의 문화를 육성하기 위한 노력은 이러한 현 상황을 타개하는 데 도움이 될 것입니다.

Of a medical school’s 3 missions—education, research, and clinical services—education is often the slowest to recognize that quality improvement and change are necessary, with traditions being dominant. Efforts to nurture the quality cultures in medical schools will help to unfreeze this status quo.

Shaping a Culture for Continuous Quality Improvement in Undergraduate Medical Education

PMID: 32287081

PMCID: PMC7678663

DOI: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000003406

Free PMC article

Abstract

Purpose: This study sought to identify key features of an organizational quality culture and explore how these features contribute to continuous quality improvement of undergraduate medical education.

Method: Between July and December 2018, researchers from Maastricht University in the Netherlands conducted a multicenter focus group study among 6 education quality advisory committees. Participants were 22 faculty and 18 student representatives affiliated with 6 medical schools in the Netherlands. The group interviews focused on quality culture characteristics in relation to optimizing educational development, implementation, evaluation, and (further) improvement. Template analysis, a stepwise type of thematic analysis, was applied to analyze the data.

Results: Five main themes resembling quality culture constituents to continuous educational improvement were identified: (1) fostering an open systems perspective, (2) involving stakeholders in educational (re)design, (3) valuing teaching and learning, (4) navigating between ownership and accountability, and (5) building on integrative leadership to overcome tensions inherent in the first 4 themes. A supportive communication climate (which can be fueled by the organization's leaders) contributes to and is integrated within the first 4 themes.

Conclusions: The results call for a shift away from static quality management approaches with an emphasis on control and accountability toward more flexible, development-oriented approaches focusing on the 5 themes of a culture for continuous quality improvement. The study provides new insights in the link between theory and practice of continuous quality improvement. Specifically, in addition to quality management systems and structures, faculty's professional autonomy, collaboration with peers and students, and the valuing of teaching and learning need to be amplified.

'Articles (Medical Education) > 교육과정 개발&평가' 카테고리의 다른 글

| CanMEDS 의사 역량 프레임워크에서 새로 등장하는 개념들 (Can Med Educ J. 2023) (0) | 2024.01.20 |

|---|---|

| 졸업후의학교육에서 공유의사결정을 위한 EPA 식별하기: 국가 델파이 연구(Acad Med, 2021) (0) | 2024.01.02 |

| 역량중심의학교육 도입: 앞으로 나아가기(Med Teach, 2017) (0) | 2023.11.30 |

| 적응적 의과대학 교육과정: 지속적 개선을 위한 모델(Med Teach, 2018) (0) | 2023.11.30 |

| 미국 의료시스템과학 교육의 한국 도입과 그 비판(Korean J Med Hist, 2022) (0) | 2023.11.16 |