역량중심의학교육을 묘사할 때의 긴장: 캐나다 핵심 오피니언 리더 연구(Adv Health Sci Educ Theory Pract. 2021)

Tensions in describing competency‑based medical education: a study of Canadian key opinion leaders

Jonathan Sherbino1,5 · Glenn Regehr2 · Kelly Dore3 · Shiphra Ginsburg4

소개

Introduction

역량 기반 의학교육(CBME)은 새로운 교육 프레임워크가 아니라 1978년에 처음 도입되었습니다(McGaghie et al., 1978). 또한, 성과 기반 교육의 특수한 유형으로서 그 기원은 1960년대로 거슬러 올라갑니다(Morcke 외, 2013). 1990년대에 CanMED 및 ACGME 핵심 역량과 같은 역량 프레임워크가 도입되면서(Frank 외, 2017; Holmboe 외, 2016) 의학교육 시스템 내에서 CBME로의 전환이 활성화되었고, 이는 현재 전 세계적으로 널리 퍼져 있으며 특히 모든 대학원 의학교육(PGME) 프로그램이 CBME 모델로 전환하고 있는 캐나다에서 영향력을 발휘하고 있습니다.

Competency-based medical education (CBME) is not a new education framework (Harden, 1999); it was initially introduced in 1978 (McGaghie et al., 1978). Moreover, as a special type of outcomes-based education it traces its origins to the 1960s (Morcke et al., 2013). The introduction of competency frameworks such as CanMEDs and the ACGME Core competencies in the 1990s (Frank et al., 2017; Holmboe et al., 2016) reinvigorated a transition to CBME within medical education systems that is now widespread around the world and particularly influential in Canada, where all postgraduate medical education (PGME) programs are transitioning to a CBME model.

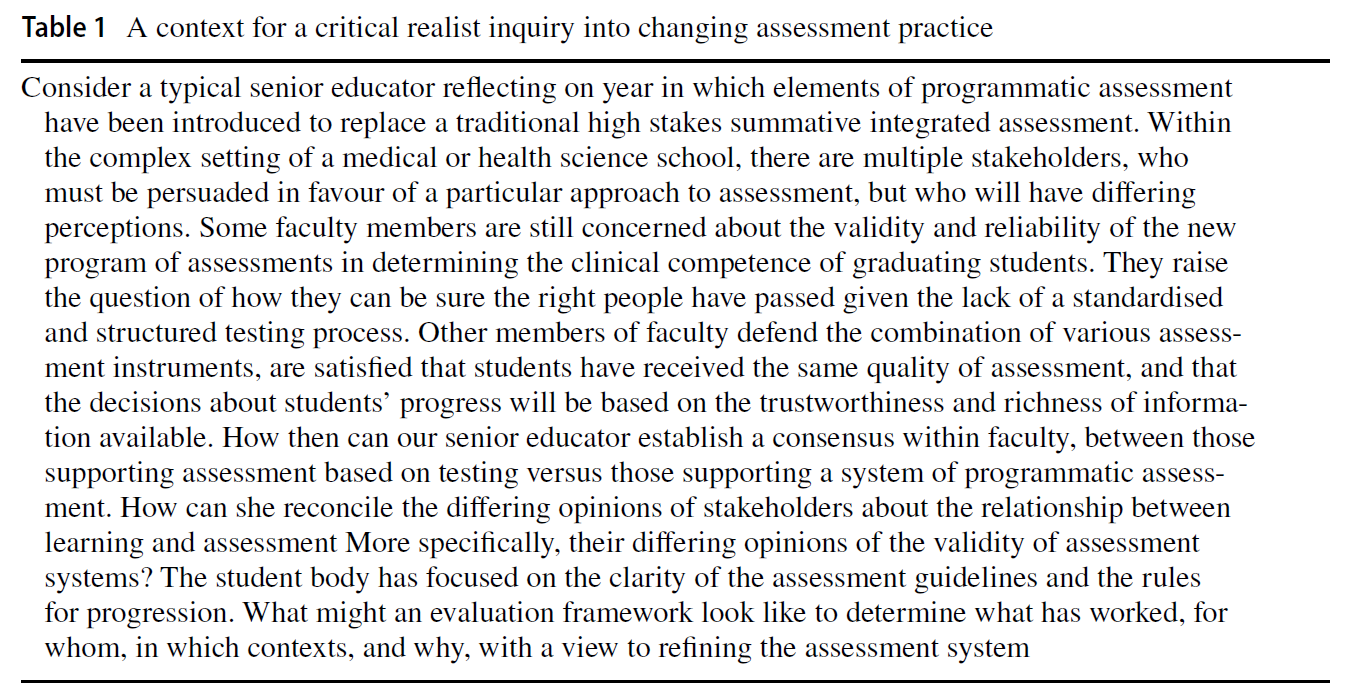

오랜 역사와 국제적으로 의학교육 시스템에 CBME가 지속적으로 도입되고 있음에도 불구하고 CBME를 설명하는 데 있어 합의점을 찾는 것은 여전히 어려운 과제입니다. CBME의 한 가지 정의는 "역량에 대한 조직화된 프레임워크를 사용하여 의학교육 프로그램의 설계, 실행, 평가 및 평가에 대한 성과 기반 접근법"(Frank 외, 2010)입니다. 그러나 이 정의의 명백한 명확성에는 의학교육계에서 CBME를 개념화하는 방식이 일관성이 없고 부정확하다는 점이 숨어 있습니다. 국제 CBME 협력체(International CBME Collaborative)는 CBME 프로그램을 구성하는 주요 구성요소를 지지하지만, 이러한 표현이 널리 채택되지는 않았습니다(Van Melle 외, 2019). 최근 Brydges 등이 수행한 종합 연구에서는 CBME의 개념화에 대해 문헌 내에서 일관성 없이 적용되는 30개 이상의 가정을 확인했습니다(Brydges 등, 2020).

Despite its long history and the ongoing international adoption of CBME into medical education systems, consensus in describing CBME remains a challenge. One definition of CBME is: “an outcomes-based approach to the design, implementation, assessment, and evaluation of medical education programs, using an organizing framework of competencies” (Frank et al., 2010). However, the apparent clarity of this definition belies the inconsistency and imprecision with which the medical education community conceptualizes CBME. While the International CBME Collaborative endorses key components that comprise a CBME program, this articulation has not been widely adopted (Van Melle et al., 2019). A recent synthesis by Brydges et al. identified more than 30 assumptions, inconsistently applied within the literature, about the conceptualization of CBME (Brydges et al., 2020).

위탁 가능한 전문 활동(EPA) 및 마일스톤과 같은 주요 CBME 용어는 여러 관할권에서 공통적으로 사용되지만, 관할권마다 그 의미와 설계가 다릅니다(Englander 외, 2017; Hawkins 외, 2015). 캐나다에서 PGME 교육을 인증하는 두 대학은 CBME에 대한 접근 방식이 다릅니다.

- 캐나다 왕립 의사 및 외과의사 대학은 마일스톤으로 정의된 교육 단계, 맞춤형 임상 경험 및 교육, EPA 데이터를 사용하여 진도 결정을 내리는 역량 위원회를 통해 CBME를 운영합니다(캐나다 왕립 의사 및 외과의사 대학, 2020).

- 캐나다 가정의학회는 결과 역량을 명확히 정의하고 현장 기록을 활용한 종단적 관찰과 업무 기반 평가를 강조합니다(Ellaway 외, 2018).

역량 프레임워크의 한계(Lingard & Hodges, 2012; Norman 외, 2014; Talbot, 2004)와 실행의 정치성(Boyd 외, 2018; Whitehead & Kuper, 2017)에 대한 논의는 합의된 출발점이 없다는 점에서 주목할 만합니다. 예를 들어, Norman 등은 CBME에 대한 비평에서 CBME의 개념화, 심리측정 및 측정 문제, 실행의 로지스틱스 등 세 가지 관련 영역의 긴장을 풀기 위해서는 각기 다른 이론적 근거와 일련의 가정에서 출발해야 한다고 말합니다(Norman 등, 2014).

Key CBME terms, such as entrustable professional activities (EPAs) and milestones, while common across jurisdictions, possess different meanings and design between jurisdictions (Englander et al., 2017; Hawkins et al., 2015). In Canada, the two colleges accrediting PGME training differ in their approaches to CBME.

- The Royal College of Physicians and Surgeons of Canada operationalizes CBME via stages of training defined by milestones, tailored clinical experiences and instruction, and competence committees making progression decisions using EPA data (Royal College of Physicians & Surgeons of Canada, 2020).

- The College of Family Physicians of Canada articulates outcome competencies and emphasizes longitudinal observation and work-based assessments using field notes (Ellaway et al., 2018).

Debate on the limitations of competency-frameworks (Lingard & Hodges, 2012; Norman et al., 2014; Talbot, 2004) and the politics of implementation (Boyd et al., 2018; Whitehead & Kuper, 2017) are notable for a lack of an agreed starting position. For example, Norman et al., in their critique of CBME, unpack tensions in three related areas—conceptualization of CBME, issues of psychometrics and measurement, and logistics of implementation—each of which require starting with a different theoretical basis and set of assumptions (Norman et al., 2014).

따라서 학문적 담론은 정교하고 명확한 두 입장 간의 논쟁이 아니라 다양한 관점과 여러 수준에서 다양한 가정을 전제로 의견 불일치가 발생하는 것입니다. 이러한 각각의 예는 집단적 수용 실어증(즉, 문자나 구어를 이해하지 못하는 상태)을 상징하는 담론을 제시하며, 정의, 가정 및 시작 입장에 대한 명시적인 표현이 부족하다는 점에서 주목할 만합니다. 학문적 담론의 목표가 반드시 합의의 도출일 필요는 없지만, 최선의 경우 집단적인 의미의 공동 구성과 논쟁 중인 내용에 대한 명확한 이해가 수반되어야 합니다. 이는 비판과 대화에 참여하기 전에 가정, 목표, 가치가 명확하지 않으면 이루어질 수 없습니다. 출발점이 모호하고 부정확한 담론은 커리큘럼 실행에 영향을 미치고, 프로그램 평가를 저해하며, 교육 자원을 소모하고, 서로 다른 목적을 위해 일하는 교육 공동체를 분열시킵니다. 의학교육 커뮤니티의 구성원들이 같은 단어를 사용하지만 서로 다른 의미를 갖는다면 문제가 됩니다.

Thus, the academic discourse is not a debate between two elaborated and explicit positions; rather disagreement occurs across multiple perspectives and several levels with many differing assumptions. Each of these examples suggest a discourse emblematic of a collective receptive aphasia (i.e. inability to understand written or spoken language), notable for a lack of an explicit articulation of definitions, assumptions and starting positions. While the goal of academic discourse need not be the development of consensus, at its best, it involves a collective co-construction of meaning and clear understanding of what is under debate. This cannot occur unless assumptions, goals and values are clear before engaging in critique and dialogue. A discourse with fuzzy and imprecise starting positions impacts curriculum implementation, impairs program evaluation, consumes educational resources and fractures education communities working at cross purposes. It matters if members of the medical education community use the same words but mean different things.

이러한 문제를 해결하려면 교육자, 관리자, 임상의가 CBME에 대해 이야기하고 생각하는 다양한 방식을 이해하여 담론을 보다 명확하게 하는 것이 중요합니다. 그렇다고 해서 CBME의 단일 개념화가 바람직한 기대치라는 것은 아닙니다. 오히려 다양한 맥락과 환경에서 CBME가 어떻게 개념화되는지를 조명함으로써 서로 다른 가정을 명확히 하고, 교육 커뮤니티 전반의 대화를 개선할 수 있는 토대를 제공할 수 있을 것입니다.

To redress this concern, it is critical to understand the different ways educators, administrators and clinicians are talking and thinking about CBME with the goal to bring greater clarity to the discourse. This is not to suggest a single conceptualization of CBME is a desirable expectation. Rather, illumination of how CBME is conceptualized in various contexts and environments would clarify differing assumptions, thereby providing a foundation on which to improve dialogue across the education community.

CBME의 본질에 대한 합의가 부족한 상황에서 이 연구의 목적은 캐나다의 주요 오피니언 리더들이 역량 기반 의학교육의 철학과 실천을 어떻게 설명하는지 탐구하는 것입니다. 이 연구가 교육적 주장을 뒷받침하는 다양한 가정과 출발점을 밝혀냄으로써 CBME에 대한 대화와 토론을 개선하는 데 도움이 되기를 바랍니다.

Given the lack of consensus about the nature of CBME, the purpose of this study is to explore how Canadian key opinion leaders describe the philosophy and practice of competency-based medical education. Hopefully, this study will lead to improved dialogue and debate about CBME by elucidating the variety of assumptions and starting positions informing educational arguments.

연구 방법론

Methodology

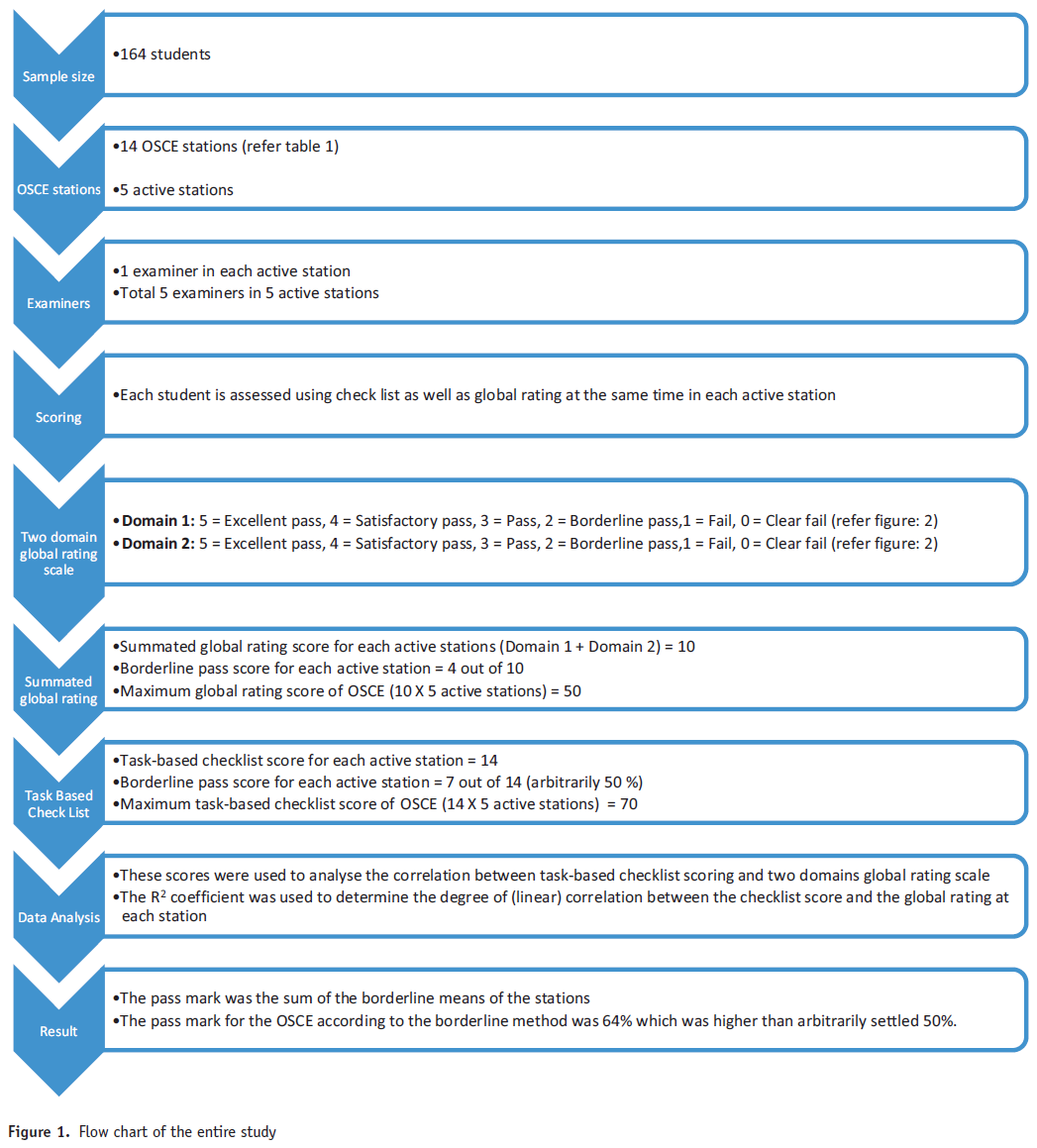

구성주의 근거 이론의 원칙을 채택하여 질적 주제 분석을 수행했습니다(Charmaz, 2000; Stalmeijer 외, 2014). 구성주의적 근거 이론은 현재 적절한 이론이 존재하지 않는 사회 현상을 탐구하는 데 매우 적합합니다(차트마즈, 2006). 이 패러다임은 우리의 목표가 현재 CBME의 원리와 실천이 개념화되는 방식에 대해 참가자들과 함께 폭넓게 이해하는 것이었기 때문에 특히 적절하다고 생각했습니다. 민감화개념에는 CBME의 현재 정의와 프레임워크가 포함되었습니다.

A qualitative thematic analysis was conducted (Charmaz, 2000; Stalmeijer et al., 2014), adopting the principles of constructivist grounded theory. Constructivist grounded theory is well suited to explore social phenomena for which no adequate theory currently exists (Chartmaz, 2006). This paradigm was felt to be particularly appropriate given that our goal was to co-construct a broad understanding with our participants of the ways in which the principles and practices of CBME are currently conceptualized. Sensitizing concepts included current definitions and frameworks of CBME.

분석에 들어가기 전에 연구팀은 CBME와 관련된 각자의 입장과 가정을 논의하고 명확히 했습니다. JS는 CanMEDS 2015 프레임워크의 공동 편집자이며 캐나다에서 응급의학을 위한 국가 CBME 커리큘럼의 시행을 주도했습니다. SG는 CBME의 평가 및 피드백을 검토하는 연구를 수행하며 내과 전문의로서 연구 당시 내과는 CBME의 파일럿 단계에 있었습니다. KD는 캐나다에서 CBME를 검토하는 장학금과 보다 광범위한 평가 연구를 수행했습니다. GR은 캐나다 왕립 의사 및 외과의 대학에서 컨설턴트로 활동하며 CBME와 관련된 커리큘럼 요소를 개선했습니다. 분석 전반에 걸쳐 저널링과 그룹 토론을 통해 반성적 사고를 촉진했습니다.

Before engaging in analysis, the research team discussed and articulated their stances and assumptions in relation to CBME. JS is a co-editor of the CanMEDS 2015 framework and led the implementation of a national CBME curriculum for emergency medicine in Canada. SG conducts research examining assessment and feedback in CBME and is an academic internist; internal medicine was in the pilot phase of CBME at the time of study. KD has conducted scholarship examining CBME in Canada and research in assessment more broadly. GR served as a consultant with the Royal College of Physicians and Surgeons of Canada refining curricular elements relevant to CBME. Reflexivity was promoted via journaling and group discussion throughout the analysis.

주요 오피니언 리더는 이메일을 통해 모집했습니다. 연구팀은 캐나다의 CBME 시행과 관련된 다양한 임상 분야, 학문적 역할, 기관 및 지역을 반영하여 의도적인 샘플링 전략을 사용하여 잠재적 참가자 목록을 작성했습니다. 오피니언 리더는 CBME 이니셔티브를 실행, 연구 또는 감독하는 국가적 차원에서 전문적인 영향력을 가진 개인으로 정의했습니다. 샘플링 전략은 의도적으로 CBME의 설계 또는 대화에 영향을 미치거나 잠재적 영향력을 가진 개인을 찾았습니다. 이 전략은 참가자가 연구에 포함될 가능성이 있는 오피니언 리더를 추가로 추천할 수 있는 눈덩이 모집 전략으로 보완되었습니다.

Key opinion leaders were recruited by email. The research team compiled a list of potential participants using a purposeful sampling strategy, reflecting diversity of clinical disciplines, academic roles, institutions, and geography relevant to the Canadian implementation of CBME. Opinion leaders were defined as individuals with professional influence at a national level that were implementing, studying or overseeing CBME initiatives. The sampling strategy intentionally sought individuals whose influence or potential influence impacted the design of or dialogue about CBME. This strategy was complemented by a snowball recruitment strategy, where participants could nominate additional opinion leaders for potential inclusion in the study.

반구조화된 전화 인터뷰는 한 명의 연구자(KD)가 진행했습니다. 인터뷰 중에 참가자들은 CBME에 대한 자신의 철학과 실제 적용 방법을 설명하도록 요청받았습니다. 데이터 수집과 함께 분석을 시작할 수 있도록 각 인터뷰에 대한 비식별화된 녹취록이 작성되었습니다. 인터뷰 가이드는 질문의 명확성을 보장하기 위해 분석 대상에 포함되지 않은 두 명의 보건 전문직 교육자와 함께 시범적으로 사용되었습니다. 인터뷰 가이드는 분석이 진행됨에 따라 새로운 인사이트를 다루기 위해 수정되었습니다. 최종 인터뷰 가이드는 '부록'을 참조하세요.

Semi-structured phone interviews were conducted by a single researcher (KD). During the interviews, participants were asked to describe their philosophies of CBME and how they were applied in practice. Verbatim, de-identified transcripts of each interview were created that allowed analysis to begin alongside data collection. The interview guide was piloted with two health professions educators, not included in the analysis, to ensure clarity of the questions. The interview guide was modified as the analysis progressed to address emerging insights. See “Appendix” for the final interview guide.

두 명의 연구원(KD와 SG)이 각 인터뷰 녹취록을 읽고 2~3번의 인터뷰가 끝날 때마다 한 줄씩 코딩을 시작했습니다. 데이터 분석은 데이터와 식별된 코드를 지속적으로 비교하고 앞뒤로 이동하는 반복적인 과정으로 진행되었습니다. 오픈 코딩이 완료된 후 축 코딩이 시작되었고, 데이터에서 핵심 주제가 확인되면 선택적 코딩이 이어졌습니다. 이 과정에서 두 연구자는 여러 차례 만나 코드를 검토하고 이견이 있을 경우 합의를 통해 해결했습니다. 합의에 도달할 때까지 전체 연구팀과 여러 차례 토론을 진행했습니다. 주제별 포화 상태에 도달했다고 주장하지는 않지만, 각 주제에 대한 심층적인 이해를 발전시킬 수 있을 만큼 데이터가 풍부하다고 판단될 때까지 분석을 계속했습니다(Hennink 외, 2017). 이 시점에서 모집은 중단되었습니다.

Two researchers (KD and SG) read each interview transcript and began line by line coding after every 2 to 3 interviews. Data analysis proceeded in an iterative process, using constant comparison and moving back and forth between the data and identified codes. Axial coding commenced after open coding was complete, followed by selective coding once key themes were identified in the data. During this process the two researchers met several times to review the codes and to resolve disagreements by consensus. Multiple discussions occurred with the entire research team until consensus was reached. While we don’t claim to have achieved thematic saturation, we continued our analysis until we reached sufficiency; that is, the data were deemed rich enough to develop an in-depth understanding of each theme (Hennink et al., 2017). At this point, recruitment ceased.

코딩과 데이터의 패턴 검색을 용이하게 하기 위해 QSR NVivo12를 사용했습니다. 분석 결정을 메모하고 기록하여 감사 추적을 유지했습니다.

QSR NVivo12 was used to facilitate coding and the search for patterns in the data. An audit trail was maintained via memoing and recording analytic decisions.

2018년 11월 캐나다 맥마스터 대학교에서 열린 전국적 공개 회의의 맥락에서 수정된 통합 지식 사용자 확인 프로세스를 수행하여 관련 지식 사용자가 연구 결과의 해석과 결과 전파를 도울 수 있도록 했습니다. (캐나다 보건 연구소, 2021). 이 회의의 초청장은 모든 캐나다 대학과 국립 의학교육 기관에 공개 모집을 통해 발송되었으며, PGME 분야에서 전국적인 인지도를 가진 교육자, 연구자 및 지도자를 찾았습니다. 이 회의의 목적은 캐나다에서 시행되고 있는 CBME의 목표와 과제에 대한 다양한 관점의 실시간 대화를 가능하게 하고, 문헌의 격차를 바탕으로 CBME를 뒷받침하는 가정을 시험하는 장학 우선순위를 파악하는 것이었습니다. 회의 둘째 날에는 오피니언 리더 인터뷰에 대한 예비 분석 결과를 발표하고 소규모 및 대규모 그룹 토론을 진행하여 참가자들로부터 피드백을 구했습니다. 참가자들은 예비 결과의 관련성, 공감대, 유용성을 고려하고 토론했습니다. 회의 중에 현장 메모를 작성하여 최종 분석에 반영했습니다. 캐나다 교육계는 상대적으로 규모가 작기 때문에 이 회의에는 일부 연구 참여자가 참석했지만, 익명성을 보장하기 위해 예비 결과 발표 중에는 이들의 신원을 밝히지 않았습니다.

A modified integrated knowledge user checking process was conducted in the context of a national, open meeting held at McMaster University, Canada, November, 2018 to allow relevant knowledge users to aid in the interpretation of the findings and the dissemination of results. (Canadian Institutes of Health Research, 2021). Invitations for the meeting were sent out via an open call to all Canadian universities and national medical education organizations seeking educators, researchers, and leaders with a national profile in PGME. The expressed purpose of the meeting was to enable a real-time dialogue across differing perspectives on the goals and challenges of CBME as implemented in Canada, and to identify scholarship priorities, based on gaps in the literature, that test the assumptions underpinning CBME. On day two of the meeting feedback was solicited from participants by presenting a preliminary analysis of the opinion leader interviews and holding small and large group discussions. Participants considered and discussed the relevance, resonance and utility of preliminary results. Field notes were taken during the meeting and were incorporated into the final analysis. Because the Canadian education community is relatively small, some research participants were present at this meeting; they were not identified during the presentation of preliminary findings to ensure anonymity.

연구윤리위원회의 승인을 받았습니다(해밀턴 통합 연구윤리위원회 #5338).

Research ethics board approval was received (Hamilton Integrated Research Ethics Board #5338).

조사 결과

Results

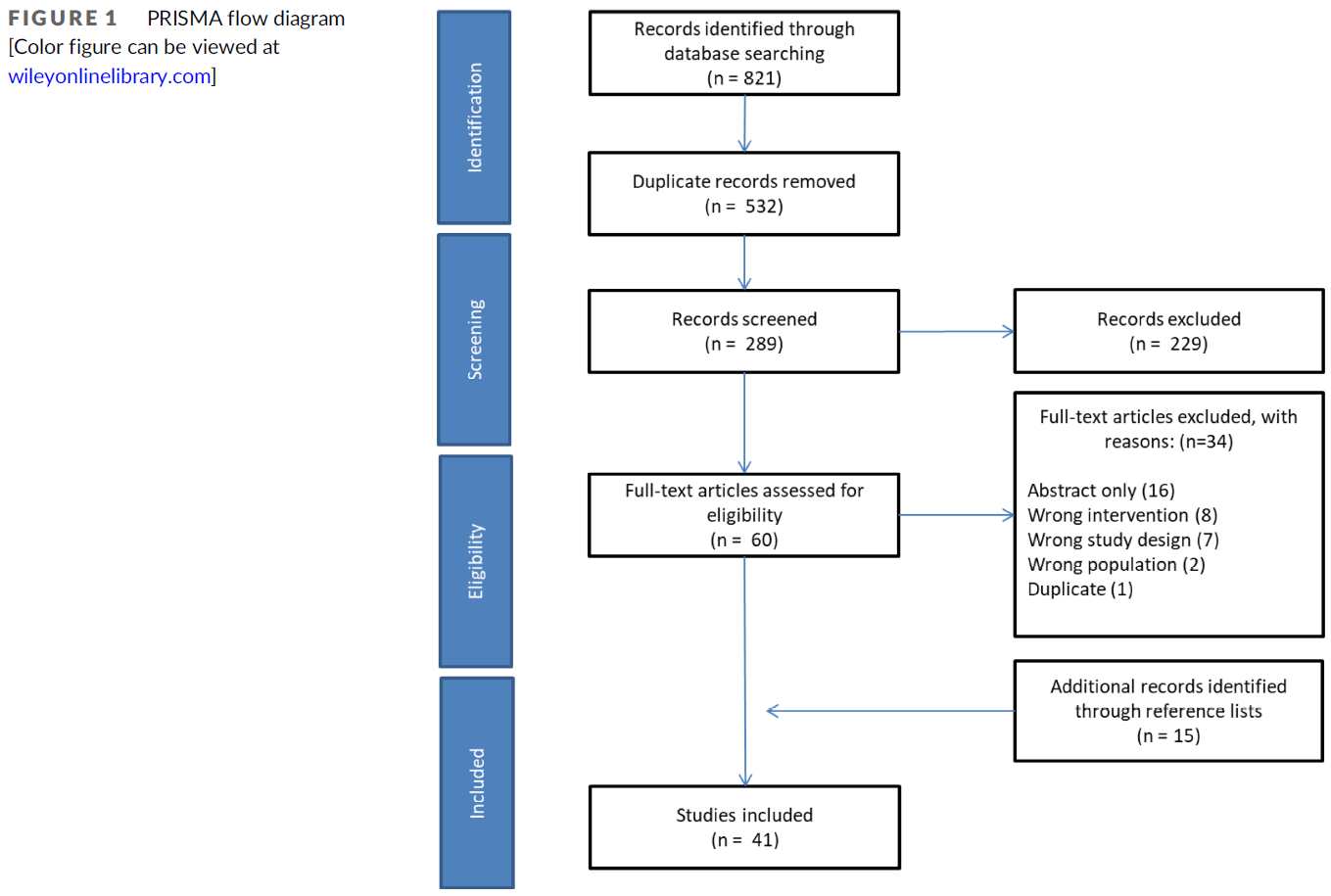

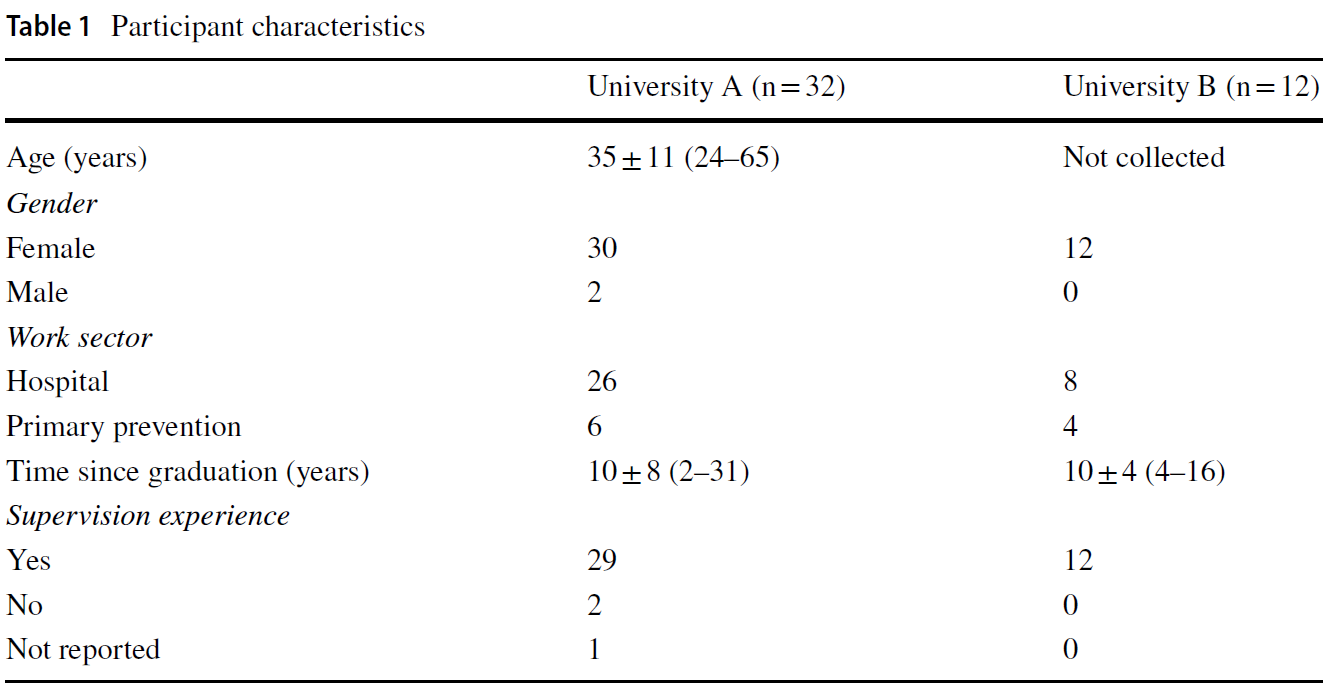

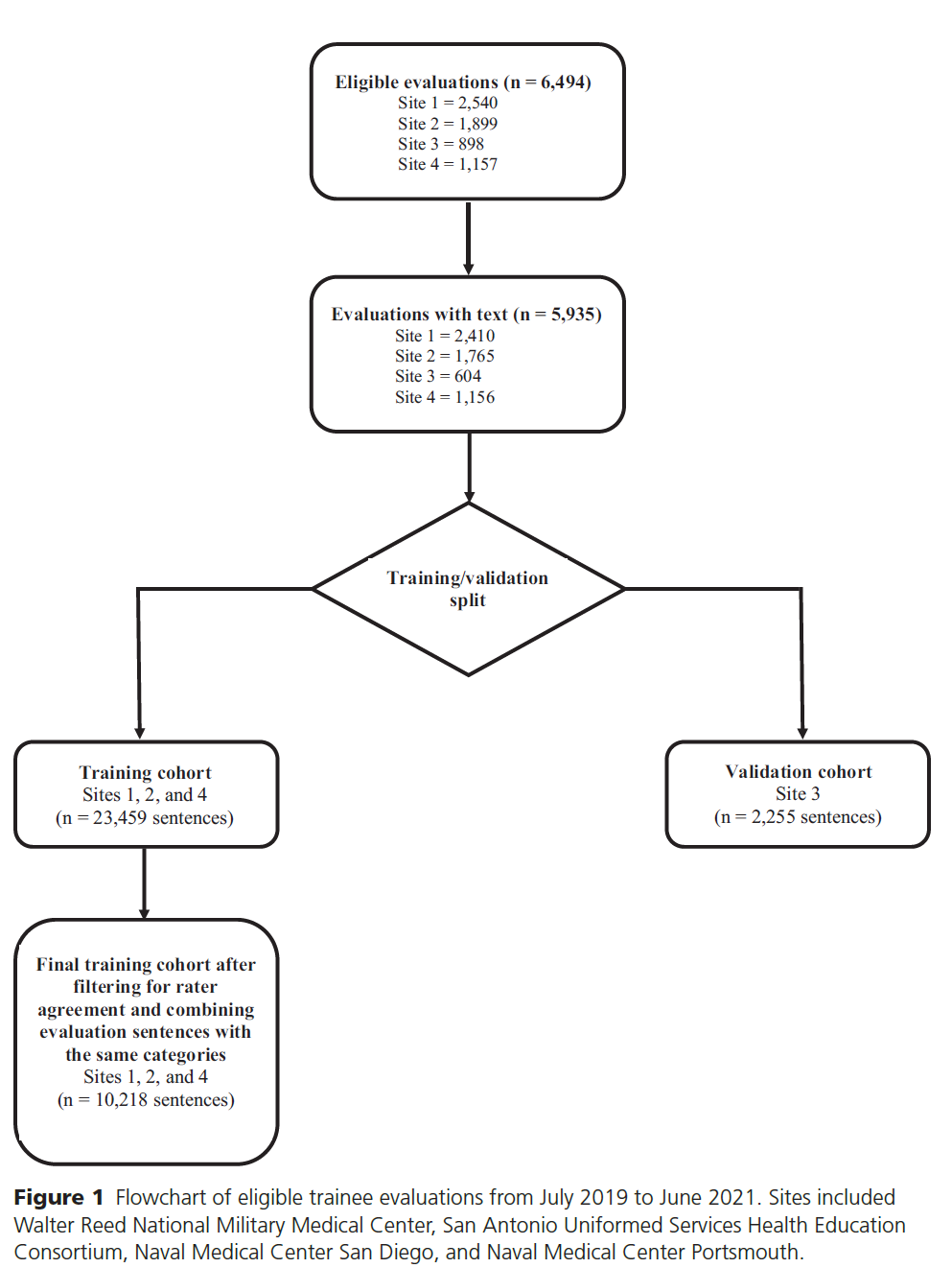

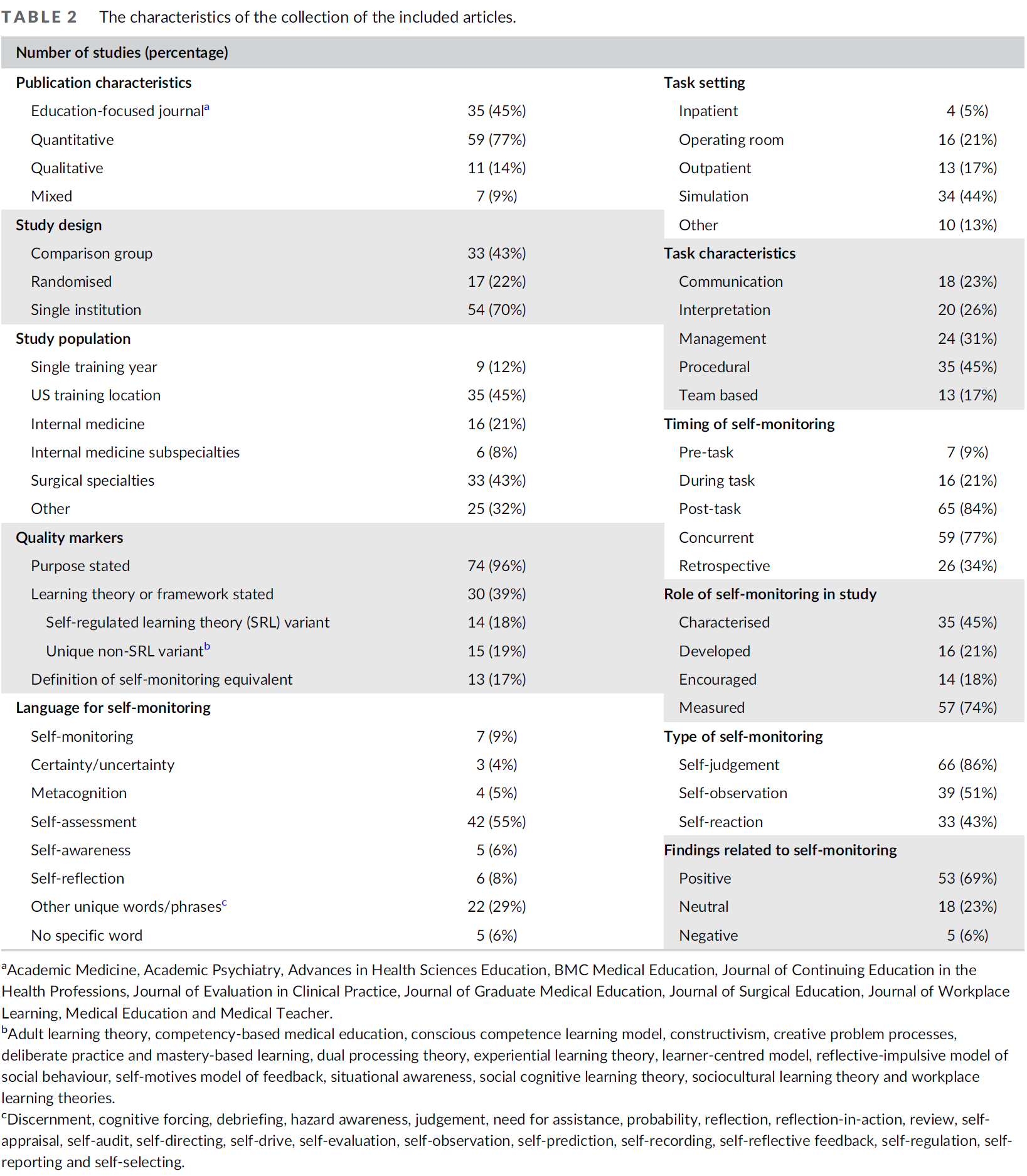

2018년 9월부터 2018년 11월까지 17건의 반구조화 인터뷰를 실시했습니다. 총 17개 중 10개 대학, 캐나다 왕립 의사 및 외과의 대학, 캐나다 가정의학과 대학, 캐나다 의료 위원회를 대표했습니다. 참가자들은 스스로 교육 연구자(9명), 교육 리더(6명), 프로그램 책임자(3명), 전문의(9명), 가정의학과 의사(3명)라고 밝혔습니다. 43명의 개인이 통합 지식 사용자 확인 프로세스에 참여했습니다. 11개 대학, 캐나다 왕립 의사 및 외과의 대학, 캐나다 가정의학과 대학, 캐나다 의학 협의회가 대표로 참여했습니다. 참가자들은 스스로를 교육 연구자(19명), 교육 리더(20명), 프로그램 디렉터(4명), 전문의(16명), 가정의학과 의사(4명)라고 밝혔습니다.

We conducted 17 semi-structured interviews between September 2018 and November 2018. They represented 10 (out of 17) universities, the Royal College of Physician and Surgeons of Canada, the College of Family Physicians of Canada and the Medical Council of Canada. Participants self-identified as education researchers (9), education leaders (6), program directors (3), specialist physicians (9), and family physicians (3). Forty-three individuals participated in the integrated knowledge user checking process. Eleven universities, the Royal College of Physicians & Surgeons of Canada, the College of Family Physicians of Canada and the Medical Council of Canada were represented. Participants self-identified as education researchers (19), education leaders (20) program directors (4), specialist physicians (16) and family physicians (4).

전반적으로 참가자들은 CBME에 대해 열정적으로 토론에 참여했습니다. 그러나 CBME나 그 핵심 구성요소를 설명하는 데 있어 하나의 지배적인 프레임을 확인할 수는 없었습니다. 일부 참가자는 CBME의 기본 개념 모델을 강조한 반면, 다른 참가자는 주로 실용적인 측면에서 설명의 틀을 잡았습니다. 이 담론은 특정한 입장의 양극성 없이 다양한 관점이 제시되었다는 점에서 주목할 만했습니다. 참가자 간의 관점에 대한 합의와 공통점은 제한적이었습니다. 이러한 불일치는 아래에서 자세히 설명하는 것처럼 CBME의 여러 측면에서 나타났습니다.

Overall, participants were engaged and passionate in discussing CBME. However, we could not identify one dominant framing for describing CBME or its key components. Some participants emphasized CMBE’s underlying conceptual models, while others framed their descriptions predominantly in practical terms. The discourse was notable for its multiple perspectives without a specific polarity of positions. There was limited agreement and commonality of perspective between participants. These discrepancies manifested in a number of aspects of CBME as elaborated below.

CBME를 정의하는 철학과 이론

Philosophies and theories that define CBME

면접관이 직접 질문했을 때, 대부분의 참가자들은 CBME를 뒷받침하는 교육 철학이나 이론을 즉시 파악하는 데 어려움을 겪었습니다. 많은 참가자가 이전에 이 질문을 자세히 생각해 본 적이 없다고 답했습니다. 한 참가자의 말처럼, "제가 그냥 뱉어낼 수 있는 것이 아닙니다. 혀끝에 있는 것이 아니라 뇌의 앞쪽에 있는 것이죠." (P9) 이 참가자는 커리큘럼 변경을 주도하는 기관에서조차 결정할 수 없는 부분이라고 덧붙였습니다: "저는 지금 이 순간에도 왕립대학의 CBME에 대한 철학이 무엇인지 잘 모르겠습니다." (P9) 참가자들은 종종 CBME의 교육 철학에 대한 논의를 회피하고 응용 또는 디자인 기능에 집중하는 것을 선호했습니다.

When directly asked by the interviewer, most participants struggled to immediately identify an education philosophy or theory that underpinned CBME. Many indicated that they had not previously considered this question in detail. As articulated by one participant, “It’s not just like I can spit out things. They are not on the tip of my tongue, on the front of my brain.” (P9) This participant further expressed that this was not something that they could even determine from the institutions leading the curricular change: “You know what, I don’t even know at this moment—I can tell you what the Royal College’s philosophy is on CBME.” (P9) Frequently, participants would sidestep the discussion of the educational philosophy of CBME, preferring to focus on applied or design features.

저는 실용주의자이기 때문에 CBME의 다양한 의미와 그 철학적 토대에 대한 광범위한 대화에 너무 얽매이지 않고 좀 더 실용적으로 접근하려고 노력합니다. (P6)

I’m a pragmatist, and don’t get too caught up with the extensive dialogues that’s occurred about the various meanings of CBME and its philosophical underpinnings and try to be more practical about it. (P6)

대부분의 참가자들은 이러한 과정을 통해 CBME의 설계를 뒷받침하는 이론적 입장을 구축할 수 있었습니다. 그러나 이러한 입장은 일관성이 부족하고 때로는 모순되기도 했습니다. 예를 들어, 한 참가자는 CBME의 기본 이론이 행동주의적 입장을 취하고 있다고 설명했습니다: "철학적, 개념적으로는 행동주의적 접근법입니다... 행동주의적 입장을 취하지 않는다면 역량, 즉 CBME 접근법을 믿지 않는 것은 어렵다고 생각합니다." (P16) 인터뷰 후반부에 같은 참가자는 "역량 모델은 절대적으로 생산 모델입니다. 결과를 정의하고, 가르칠 내용을 정의하고, 평가하고, 결과에 도달하는 것이죠. "(P16) 이와는 대조적으로 다른 참가자는 다음과 같이 주장했습니다.

When pushed, most participants were able to construct a theoretical stance that supported the design of CBME. Yet, these positions lacked uniformity and sometimes were contradictory. For example, one participant described the underlying theory of CBME as taking a behaviourist stance: “Philosophically, conceptually, it’s a behaviorist approach … I mean I think that it is hard not to believe in a competency, CBME approach, unless you take a behaviourist stance.” (P16) Later in the interview, the same participant suggested that “a competency model is absolutely a production model. You define the outcome, you define what you teach, you assess it, and you reach the outcome. “(P16) In contrast, a different participant asserted the following.

CBME는 학습이 학습자와 사회 시스템의 맥락의 상호작용이라는 구성주의를 강력하게 참조하고 있습니다."(P10)

CBME is strongly referencing constructivism—that learning is very much an interaction of the learner and context of a social system.(P10)

참가자들이 다양하게 언급한 교육 관련 개념과 이론으로는 자기결정 이론, 자기조절 학습, 비고츠키의 근거리 발달 영역, 숙달 학습, 정체성 이론, 교육 동맹, 의도적 실천, 학습자 중심주의, 성장 마인드, 위탁성 등이 있었습니다. "하나의 철학이나 단일 구조가 아니며" CBME가 "묶음"(P10)에 가깝다는 데는 대체로 동의하는 것처럼 보였지만, CBME를 뒷받침하는 일련의 구조가 "완전한 패키지"(P10)인지, CBME가 효과적으로 "모든 것을 하나로 묶는"(P9) 것인지, 아니면 "하나의 라벨 아래 상당히 자의적으로 묶인 여러 원칙과 실천"인지에 대해서는 합의가 덜 이루어졌습니다. (P4).

Specific education-related concepts and theories that were variously invoked by different participants included: self-determination theory, self-regulated learning, Vygotsky’s zone of proximal development, mastery learning, identity theory, educational alliance, deliberate practice, learner centredness, growth mindset and entrustability. While there seemed to be general agreement that “it is not a single philosophy or single construct” and that CBME was more like a “bundle” (P10), there was less agreement on whether the set of constructs that underpin CBME is “a complete package” (P10), whether CBME effectively “knits them all together” (P9) or whether it is “a number of principles and practices which have been lumped together fairly arbitrarily under one label.” (P4).

어떤 경우에는 이러한 여러 이론과 철학이 일치하는 것처럼 느껴지기도 했지만, 때로는 충돌하는 경우도 있었습니다.

- 예를 들어, 한 참가자는 코치가 학습자가 목표를 설정하는 데 도움을 줄 수 있다는 점에서 종적 관계 내 코칭의 원칙이 자기조절학습의 개념과 잘 부합한다고 설명했습니다. 그러나 이 참가자는 계속해서 설명했습니다: "저는 실제로 프로그램식 평가가 역량 기반 혁신이 ... 학습자의 자기조절 능력을 향상시키는 데 도움이 되는 능력을 약화시킬 수 있다고 생각합니다." (P11) 이는 역설적으로 피드백을 문서화하는 데 지나치게 집중하는 결과로 이어져 "...학습자가 상사와 함께 하는 모든 순간이 성과가 되는 것이 아니라, 그 환자와 혼자 있을 때 진정으로 하는 일이 되는" 상황으로 이어질 수 있다고 생각했습니다. (P11)

- 업무의 진정성이 결여되면 레지던트에게 진정으로 유용하거나 목표 지향적이지 않은 피드백으로 이어집니다. 또 다른 참가자는 의사가 환자 중심적이고 사회의 요구를 더 잘 충족시키기를 바라는 동시에 학습자 중심의 접근 방식을 장려하는 것 사이의 긴장을 갈등으로 인식했습니다. 한 참가자는 이렇게 설명했습니다:

While in some cases these multiple theories and philosophies were felt to be aligned, at times they were in conflict.

- For example, one participant described how the principle of coaching within a longitudinal relationship aligned well with the concept of self-regulated learning, as the coach can help the learner set goals. However, the participant went on to explain: “I actually think programmatic assessment may actually undermine the ability of competency-based innovations … to help [learners] become more self-regulating.” (P11) This was felt to result, paradoxically, in an excessive focus on documentation of feedback, which could lead to a situation where “…every moment of the learner’s day with their supervisor [is] a performance, as opposed to being authentically what they would do if they were alone with that patient.” (P11)

- The inauthenticity of the task then leads to feedback that isn’t truly useful or goal-oriented for the resident. Another participant recognized conflict was the tension between wanting physicians to be more patient-centered, and better at meeting society’s needs, while also promoting a learner-centered approach. As explained by one participant:

CBME는 환자의 결과를 기반으로 하기 때문에 약간의 모순이 있습니다. 사회의 요구가 무엇인지에 기반해야 하지만, 학생 중심이기도 하므로... 어려운 주문입니다.(P13).

It’s kind of an oxymoron a little bit – because [CBME] is based on patient outcomes. It should be based on what the needs of society are, but it is also student centered, so … it’s a tall order.(P13)

주요 운영 관행으로 정의되는 CBME

CBME defined by key operational practices

참가자들은 종종 CBME에 대한 설명을 원칙과 철학에서 벗어나 실제 운영 관행에 대한 논의로 이끌었습니다. 참가자들은 평가와 학습자-교사 관계의 본질이라는 두 가지 소주제를 두드러지게 다루었고, 이 두 가지 주제는 정기적으로 자세히 설명했습니다.

Participants often steered the description of CBME away from principles and philosophies towards a discussion of practical operational practices. Two subthemes were prominent and regularly elaborated by participants: assessment and the nature of the learner-teacher relationship.

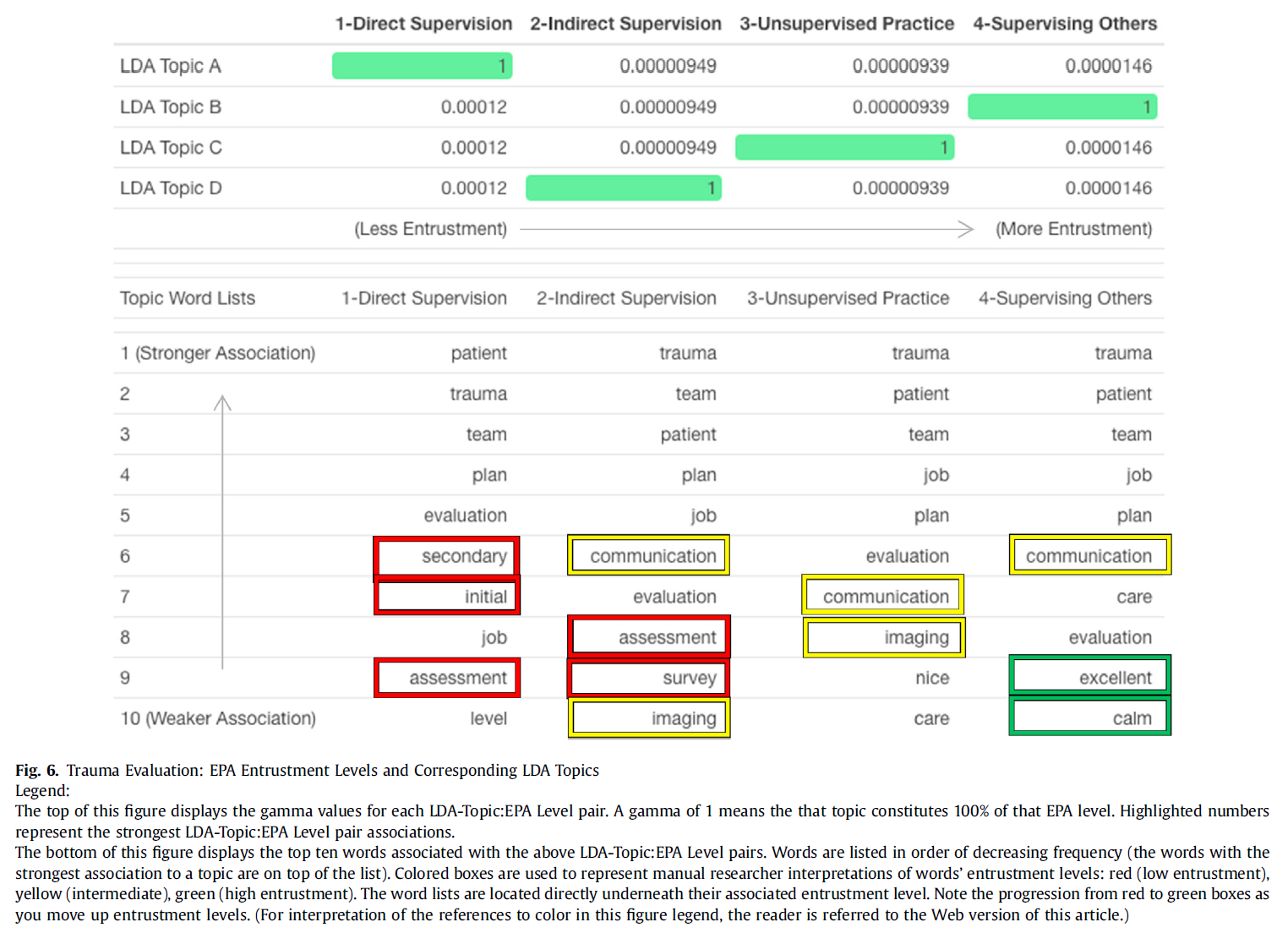

대다수의 참가자가 평가는 CBME의 기본 조직 관행으로 명시했습니다. 평가 관행에는 다음 등이 포함되었습니다.

- 학습해야 할 내용을 표시하는 지표로 EPA와 마일스톤 사용,

- 학습자의 임상 수행에 대한 직접 관찰 증가,

- 직접 관찰에 기반한 보다 빈번하고 구체적인 피드백 제공,

- 위임 판단으로 구성된 구체적이고 관찰된 수행에 대한 빈번하고 저부담의 작업장 기반 평가 사용,

- 학습자를 위한 정보에 기반한 교육 결정과 처방을 내리기 위해 대량의 (개별적으로는 저부담의) 데이터를 집계하고 해석하는 역량 위원회의 사용

Assessment was articulated as the fundamental organizing practice of CBME by a majority of participants. Assessment practices included:

- the use of EPAs and milestones as markers of what should be learned;

- increased direct observation of learners’ clinical performances;

- the provision of more frequent and more specific feedback based on direct observation;

- the use of frequent, low stakes, workplace-based assessment of specific, observed performances framed as entrustment judgements; and

- the use of competency committees to aggregate and interpret the large amount of (individually low stakes) data to make informed educational decisions and prescriptions for learners.

저에게 CBME는 더 많은 관찰과 더 많은 평가를 하는 평가 방식의 변화와 더불어 결과 기반 접근법이라고 말하고 싶습니다...(P7).

I would say CBME for me is an outcomes-based approach in addition to a change in the way we also do assessment, in having more observations, more assessments… (P7)따라서 CBME의 핵심은 ... 마일스톤과 EPA를 명시적으로 연결하고 평가를 강화하는 것입니다. (P6)

So at its core, I would find CBME is … the explicit connections of milestones and EPAs and ramped up assessments. (P6)... 그렇다면 어떤 것을 가리키며 CBME라고 말하는 것을 어떻게 정의할 수 있을까요? ... 저는 임상 역량 위원회가 그 중 하나라고 말하고 싶습니다. (P9)

…so what would define it to point at something and say that’s CBME? … I would say that it is clinical competency committees is one of those. (P9)

CBME에 대한 설명은 주로 평가와 관련된 것이었지만, 일부 참가자들은 CBME의 본질적인 특징으로서 학습자-교사 관계의 본질에 초점을 맞추었습니다. 한 참가자는 이러한 관계가 CBME의 핵심이라고 설명했습니다:

While the articulated practices of CBME were predominantly concerned with assessment, some participants focused on the nature of the learner-teacher relationship as an essential feature of CBME. One participant described this relationship as being key to CBME:

학습자가 자신에게 다가오는 모든 정보를 처리하고 자기 조절력을 키울 수 있도록 돕는 것이야말로 근본적인 개입, 즉 종단적 코치라고 생각합니다. (P11)

I actually think that’s the fundamental intervention, the longitudinal coach piece, to help the learner process all the information coming at them, to help them become more self-regulating. (P11)

코칭이라는 개념 외에도 일부 참가자는 도제식 모델에 대한 설명에서와 같이 종적 관계에 대한 다른 목적을 명시했습니다.

In addition to the idea of coaching, some participants articulated different purposes to the longitudinal relationship, such as in this description of an apprenticeship model.

저는 어떤 의미에서 이상적인 CBME는 교수진이 소수의 학습자를 보유할 수 있도록 하는 연속적인serial 도제식 모델이라고 생각합니다. 당신은 그들의 성과에 투자했습니다. 학습자와 충분한 시간을 함께 보내면서 그들의 성장을 확인할 수 있었습니다. 학습자에게 피드백을 줄 시간이 있었습니다. 피드백을 주고 난 후의 변화나 상황이 그들을 도울 수 있는지 확인할 시간이 있었습니다. (P10)

I think the ideal CBME in a way would be a serial apprenticeship model, so that you as a faculty would have a few learners. You were invested in their performance. You knew them as people—you spent enough time with them that you could see their growth. You had time to give them feedback on things. You had time to see if after feedback or things changing you could help them. (P10)

주목할 점은 종단적 관계에 대해 논의한 많은 참가자들이 이를 "종단적 평가"(P7)라고 표현했다는 점인데, 이는 개인이 CBME를 개념화할 때 평가가 얼마나 널리 퍼져 있는지 다시 한 번 보여줍니다.

Of note, many participants who discussed longitudinal relationships also framed it as “longitudinal assessment” (P7), illustrating again the pervasive role of assessment in individuals’ conceptualizations of CBME.

CBME가 해결하는 문제

Problems CBME solves

참가자들은 의학교육의 현안이나 문제 중 CBME가 해결하고자 하는 것이 무엇인지 질문했습니다. 'Failure to Fail'이 자주 언급되었는데, 이는 어려움에 처한 학습자를 식별하고 해결하려는 일반적인 무능력 또는 의지가 부족하여 필요한 교정 없이도 시스템을 진행하고 심지어 졸업할 수 있다는 의미로 설명되었습니다.

Participants were asked what current issues or problems in medical education CBME was intended to solve. ‘Failure to fail’ was a frequently cited rationale, which was described as a general inability or unwillingness to identity and address learners in difficulty, allowing them to progress through the system and even graduate without the necessary remediation.

우리는 여전히 여러 가지 이유로 실무에 적합하지 않은 의사를 실무에 투입하고 있습니다. 단지 그렇게 하지 않기가 어렵거나 우리가 알아차리지 못할 뿐입니다. (P4)

We are still entering physicians into practice who are not fit for practice for a number of reasons—it’s just hard not to, or we don’t notice. (P4)...누가 실제 시험에 불합격할 위험이 있는지 예측할 수 있지만...우리는 이런 사람들을 다룰 용기가 없습니다. (P3)

…we can predict who is at risk of failing their actual exams…and we do not have the guts to deal with these people. (P3)

이 문제는 진정한 성과를 검증할 수 있는 직접적인 관찰이 부족한 평가 시스템으로 인해 더욱 악화되었고, 대신 훈련 종료 평가의 위태로운 타당성에 의존하게 되었습니다.

This issue was compounded by assessment systems that lacked direct observation to verify authentic performance, relying instead on the precarious validity of end of training high stakes assessment.

가장 큰 문제는 직접 관찰이었습니다...... 프로그램 책임자가 환자를 한 번도 본 적이 없는 항목을 작성하는 것, 즉 아무도 환자를 관찰한 적이 없는 정보를 바탕으로 작성하는 것이기 때문에 이 평가가 처음 고안되었을 때 해결하고자 했던 큰 문제였다고 생각합니다. (P2)

The big problem was the direct observation….ITERs is [an] example where your program director is filling out an item they’ve maybe never seen you—it’s based on information that nobody has ever observed you with a patient—so I think that was the big problem it was trying to address when it was first thought of. (P2)... 프로그램 마지막에 실시하는 고부담 총괄 평가는 좋은 교육 이론에 전혀 부합하지 않는다고 생각합니다. (P15)

…the high-stake summative assessment at the end of the program is very much not – is not at all in keeping I don’t think with good educational theory. (P15)

Failure to tail이라는 생각에 묶여, 참가자들은 실무에 필요한 모든 능력을 습득했는지 확인하기 위한 현행 교육 프로그램의 엄격함에 대해 우려를 표명했습니다. 무작위로 구성된 순환 근무의 교육 시스템이 유능하고 다재다능한 의사를 배출하는 데 필요한 경험에 우연적으로 노출된다는 의견이 제시되었습니다:

Tied to the idea of failure to fail, participants expressed concern with the rigour of current training programs to ensure all necessary abilities required for practice had been acquired. It was suggested that an education system of randomly organized rotations led to haphazard exposure of the necessary experiences to produce competent, well rounded physicians:

학부든 대학원이든, 가정의학과든, 어떤 수련 프로그램을 거치더라도 일정 기간 동안 한 장소에서 근무하는 특성 때문에 우연히 한 가지 이상의 영역에 대해 배우지 못했거나 노출되지 않았거나 능력을 개발하지 못한 사람이 있을 수 있습니다. (P12) Somebody could get through a training program, whether undergrad or postgrad, family medicine, whatever,

where by chance they did not learn or were not exposed or did not develop an ability in one or more areas purely because of the nature of your in a place in a context for a period of time. (P12)

몇몇 참가자들은 사회가 필요로 하는 의사를 배출한다는 사회 계약을 이행하는 의학전문대학원 교육 시스템과 그에 따른 전문가 지위 상실 가능성에 대한 우려도 확인했습니다.

Several participants also identified concerns about the postgraduate medical educational system fulfilling the social contract to produce physicians needed by society and the attendant possibility of losing professional status.

또한 의과대학의 특권적 권위가 그동안 약화되었으며, 이는 부분적으로 의과대학이 올바른 방법을 사용하지 않았고 올바른 제품을 제공하거나 만들지 않았기 때문이라는 인식이 커지고 있습니다(P4).

There is also this growing sense…that the privilege[d] authority of medical schools has diminished over this time and that is in part because they have not used the right methods and they have not been delivering or creating the right product (P4)

CBME의 예상치 못한 결과

Unanticipated consequences of CBME

많은 참가자들은 CBME가 의사 진료의 총체적인 본질을 개별적인 능력으로 해체하는 환원주의적 역량 프레임으로 이어진다는 우려를 표명했습니다. 이러한 참가자들은 의사의 다른 교차적이고 상호 보완적인 능력과의 필수적인 상호작용을 고려하지 않고 개별 능력을 적절하게 가르치거나 평가할 수 있는지에 대해 회의적이었습니다. 또한 정의된 개별 능력의 임의적인 목록을 재조합했을 때 총체적으로 유능한 의사가 될 수 있을까요?

A number of participants expressed concern that CBME leads to a reductionist framing of competence, where the holistic nature of physician practice is deconstructed into discrete abilities. These participants were skeptical that discrete abilities could be adequately taught or assessed without considering the necessary interaction with the other intersecting and complimentary abilities of a physician. Moreover, would the arbitrary list of the defined, discrete abilities constitute a holistic competent physician when reassembled?

CBME의 가장 큰 위험 중 하나는 항목화되거나 사물을 구성 요소로 세분화하여 너무 아래로 내려가면, 우리는 이러한 구성 요소를 보고 전체가 괜찮은지 확인하고 한 단계에서 다음 단계로 이동한다는 생각으로 돌아가야 하는데, 그렇지 못하고 잡초 속으로 빠져들게 된다는 것입니다. (P3)

One of the biggest risks of CBME is that it is itemized or breaks things down into its component parts and gets—it’s too far down there, and we need to get back to thinking that we are looking at these components parts and see if the whole is okay, and move from one stage to the next, and we are not and we have gotten down into [the] weeds. (P3)어려운 점 중 하나는 역량이 어떤 것이고, 정의할 수 있는 것이며, 어떻게든 환경과 분리할 수 있는 개인의 특성이라는 가정이 있다는 것입니다. 따라서 모든 것을 EPA로 세분화하고, 누군가가 그런 일을 세 번 하는 것을 지켜본 다음 '예, 유능합니다'라고 말하면 문제가 해결된다는 생각은 잘못된 것입니다. (P5)

I think one of the challenges is there is a bit of assumption that competence is a thing, that it is a definable thing and that it somehow becomes a trait of an individual that is separable a bit from their environment. So, the idea that we can break everything down into EPAs, watch someone do those things three times and then say yes, they are competent, and our problem is solved. (P5)

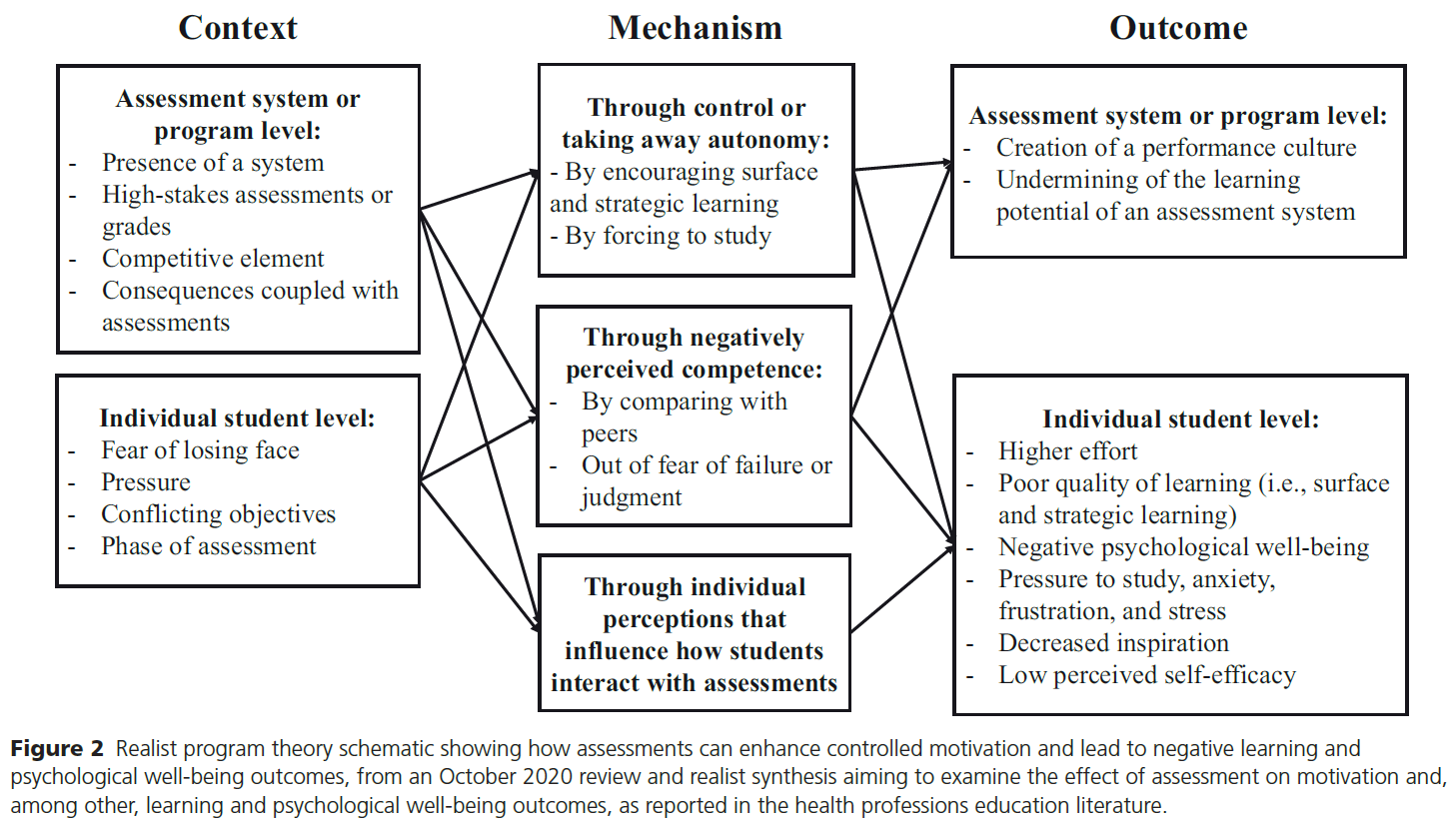

다른 참가자들은 CBME가 만들어내는 직접적인 관찰과 평가에 대한 관심 증가와 함께 전공의의 복지와 학습 환경의 본질에 대한 관심을 강조했습니다.

Other participants emphasized concern for resident wellbeing and the nature of the learning environment with the increased attention to direct observation and assessment that CBME creates.

['안전한 학습 환경'이라는 목표와 '포괄적인 문서화'라는 목표 사이에 갈등이 있습니다... 이는 [레지던트와 감독자 간의] 상호작용의 성격을 근본적으로 변화시키는데, 이는 두 사람이 똑같은 관찰을 하고 있고 단지 그들 사이의 대화일 뿐이며 아무데도 갈 필요가 없는 경우와는 대조적입니다. (P3)

[There is] conflict between the goal of ‘safe learning environments’ versus ‘comprehensive documentation’…That fundamentally changes the nature of the interaction [between resident and supervisor], as opposed to if the two of them were having the exact same observation and it was just a conversation between them and it didn’t have to go anywhere. (P3)... 우리가 낮은 수준의 평가를 자주 하려고 노력한다고 해도 레지던트들이 항상 평가를 받고 있다는 인식이나 느낌, 높은 경계심을 갖고 스트레스를 받는다는 것은 학습자의 건강과 웰빙에 부정적인 영향을 미칠 수 있다고 생각합니다. (P15)

…even though we’re trying to be frequent low stakes assessments is the perception or feeling that residents are always being assessed, being on high alert and being stressed out from that cause I think that could have negative implications for the health and wellness of our learners. (P15)

통합 지식 사용자 점검 과정에서 확인되고 널리 지지된 새로운 주제는 긍정적이고 의외의 이점에 대한 인식이었습니다. 참가자들은 CBME가 일선 임상 교사의 지식과 능력을 향상시켜 더 나은 피드백을 전달하고 더 나은 평가를 제공할 수 있다고 언급했습니다. 다양한 맥락에서 초기 관찰 결과, 임상 교사들은 이제 이전보다 더 지식이 풍부하고 정교한 방식으로 교육에 대해 '이야기'할 수 있게 되었다고 합니다. 일부 참가자들은 레지던트의 발전과 레지던트 역량에 대한 레지던트 프로그램의 종합적인 판단을 향상시킬 수 있는 개선된 피드백 및 평가 관행에 주목했습니다.

A new theme identified and widely endorsed during the integrated knowledge user checking process was acknowledgment of a positive, surprise benefit. Participants noted that CBME could enhance the knowledge and ability of front-line clinician teachers to deliver improved feedback and provide better assessments. Early observations in various contexts suggested that clinician teachers could now “talk the talk” of education in a more knowledgeable and sophisticated way than before. In some cases, participants noted improved feedback and assessment practices which could enhance residents’ progression and residency programs’ summative judgements about resident competence.

토론

Discussion

캐나다 의학교육의 주요 오피니언 리더를 대상으로 한 이 연구는 역량 기반 의학교육에 대한 일관된 정의, 설명 또는 프레임워크가 없다는 CBME 관련 문헌을 검토하면서 느낀 점을 재확인시켜 줍니다. 이는 의학교육이 부정확한 분류체계로 인해 어려움을 겪고 있기 때문에 놀라운 발견은 아닙니다(Mills et al., 2020). 전문직업성(van Mook 외, 2009), 성찰(Nguyen 외, 2014), 임상적 추론(Young 외, 2019), 문제 기반 학습(Schmidt, 1993)은 명시적이고 공통된 정의가 부족하다는 더 큰 문제를 보여주는 좋은 예입니다. 또한 의학교육 학술에서는 어휘의 결함에 대해 자주 비판을 받습니다(Eva, 2017; Walsh & Eva, 2013).

This study of Canadian medical education key opinion leaders reaffirms our sense in reviewing the literature on CBME that there is no consistent definition, description or even framing of competency-based medical education. This is not a surprising finding as medical education is plagued by an imprecise taxonomy (Mills et al., 2020). Professionalism (van Mook et al., 2009), reflection (Nguyen et al., 2014), clinical reasoning (Young et al., 2019) and problem-based learning (Schmidt, 1993) are ready examples of the larger problem of a lack of explicit and common definitions. Moreover, medical education scholarship is frequently critiqued for deficiencies in its lexicon (Eva, 2017; Walsh & Eva, 2013).

이 연구의 결과는 Lochnan 등이 최근 실시한 범위 검토에서 대부분의 출판물이 참조 표준을 인용하지 않은 채 문헌에서 CBME에 대한 여러 가지 정의가 존재한다는 사실을 입증한 것과 일치합니다(Lochnan 등, 2020). 부정확한 정의의 문제는 EPA, 마일스톤, 역량과 같은 용어가 인증 기관마다 다르기 때문에 더욱 문제가 됩니다(Englander 외., 2017; Hawkins 외., 2015).

The findings of this study are consistent with a recent scoping review by Lochnan et al. that demonstrated the multiple definitions of CBME in the literature with the vast majority of publications failing to cite a reference standard (Lochnan et al., 2020). The challenge of imprecise definitions becomes more problematic as terms such as EPAs, milestones and competence also vary between accrediting bodies (Englander et al., 2017; Hawkins et al., 2015).

이 연구의 주요 오피니언 리더들은 CBME에 대한 일관된 철학적 또는 이론적 틀을 제공하는 데 어려움을 겪었습니다. 이는 담론의 양극단을 시사하는 것이 아니라, 다양한 이슈에 걸쳐 입장이 분산되어 있음을 시사하는 결과입니다. 그러나 시너지 효과가 있든 모순적이든 사후적으로 제시된 수많은 설명 이론이 반드시 CBME의 치명적인 결함을 나타내는 것은 아닙니다. 이러한 현상은 CBME가 팀 기반 학습이나 객관적 구조화 임상 평가(OSCE)와 같은 단일 교육 개입이 아니라는 점을 반영할 수 있습니다. 오히려 참가자들이 다양한 운영 사례를 설명했다는 점을 고려할 때 CBME는 교육 번들로 더 잘 개념화될 수 있습니다. 중재 번들은 단일 중재가 효과적이지 않은 복잡한 문제(예: 환자 치료 핸드오프의 오류(Starmer et al., 2014))를 해결하기 위해 도입되었습니다. 번들에는 더 큰 목표를 달성하기 위해 여러 수준과 이해관계자를 대상으로 하는 여러 가지 상호 보완적인 개입이 포함됩니다(Wong & Headrick, 2020). 이러한 개념화에서 코칭의 빈도와 질을 높이고, 평가 횟수를 늘리고, 대중에게 더 많은 과정 투명성을 제공하는 등 CBME 번들 내에서 가능한 수많은 교육 개입은 참가자들이 생성한 다양한 이론 목록에 반영된 것처럼 수많은 지원 프레임워크를 예상할 수 있습니다.

The key opinion leaders in this study struggled to provide a coherent philosophical or theoretical framing for CBME. This is not to suggest a polarity in the discourse; rather, the findings suggest a diffuse disconnect of positions across numerous issues. However, the multitude of post hoc explanatory theories that were offered, whether synergistic or contradictory, does not necessarily indicate a fatal flaw with CBME. This phenomenon may reflect that CBME is not a single educational intervention like team-based learning or the objective structured clinical evaluation (OSCE). Rather, given that participants also described numerous operational practices, it may be that CBME is better conceptualized as an education bundle. Intervention bundles are introduced to solve complex problems (e.g., errors in patient care handoff (Starmer et al., 2014)) where no single intervention is effective. Bundles include multiple, complimentary interventions directed at multiple levels and stakeholders to achieve larger goals (Wong & Headrick, 2020). In this conceptualization, the numerous possible education interventions within the CBME bundle, such as increasing the frequency and quality of coaching, systematizing increased numbers of assessments, or providing more process transparency to the public, would anticipate numerous supporting frameworks, as reflected by the diverse list of theories generated by participants.

다양한 관점의 존재는 시스템의 각 참여자가 자신의 부족한 부분을 인식하도록 요구하며, 이를 통해 문제와 해결책에 대한 보다 정교한 정의를 반복적으로 재구성하고 공동 구성할 수 있게 해줍니다(Cristancho, 2014). 위험은 다양한 관점이 존재한다는 데 있는 것이 아니라, CBME 담론에서 이러한 다양한 관점을 인식하지 못한다는 데 있습니다. 이런 의미에서 임상의, 교육자, 관리자가 CBME를 어떻게 개념화하는지를 밝혀내는 것은 그러한 프레임워크 사이의 상호 보완적인 특성과 단일 관점의 한계를 드러냅니다. CBME를 교육 번들로 설정하면, 여러 가지 개입이 여러 가지 지원 이론과 함께 작용하며, 이 모든 것이 더 큰 조직 영역 내에서 이루어지고 있음을 명확히 알 수 있습니다. CBME의 구조화에 대한 여러 가정에 대한 명확성을 개선하면, 문헌의 담론을 개선하고, 커리큘럼 혁신을 위한 노력을 강화하며, 프로그램 평가를 위한 명확성을 제공할 수 있습니다.

The presence of multiple perspectives requires each participant in the system to be cognizant of their own lacunae and thereby enables them to iteratively reconstruct and co-construct a more sophisticated definition of the problem as well as the solution (Cristancho, 2014). The danger lies not in the multitude of perspectives, but in the failure to appreciate those multiple perspectives in the discourse on CBME. In this sense, uncovering how clinicians, educators and administrators conceptualize CBME exposes the complimentary nature between such framings and the limitations of a single perspective. Situating CBME as an education bundle makes explicit that multiple interventions are at play with multiple supporting theories, all within a larger organizing domain. Improving clarity around the multiple assumptions of the structuring of CBME may improve discourse in the literature, enhance efforts at curricular innovation, and provide clarity for program evaluations.

마찬가지로, 많은 참가자들이 강조하는 CBME의 실용적이고 무이론적인 틀(CBME가 해결한 주요 운영 사례와 문제에서 알 수 있듯이)이 결함이 있는 설계와 동일시될 필요는 없습니다. 캐나다의 전통적인 대학원 의학 교육 시스템도 명시적이고 완전히 통합된 이론적 토대 위에 구축되지 않았다는 점을 기억하는 것이 중요합니다. 오히려 학부 의학교육의 질적 문제를 해결하기 위해 개발된 실용적인 솔루션을 차용했습니다. 북미 의과대학에 대한 카네기 재단의 보고서(Flexner, 1910)를 반영한 미국의학협회의 기준은 캐나다에서 큰 영향을 미쳤습니다. 학부 의학교육 생물의학 모델이 PGME에 미친 영향은 이론적인 측면이 아니라 실용적인 측면을 따랐습니다. 같은 맥락에서 이 연구의 주요 오피니언 리더들은 한 세기 동안 최소한의 점진적 변화로 PGME를 발전시킨 후 발생한 현 세대의 문제를 해결하기 위한 실질적인 해결책으로 CBME에 대한 여러 가지 근거를 제시했습니다. 대중과 학습자 모두에게 중요한 CBME는 레지던트 수련의 책무성을 향상시킵니다(Albanese 외., 2008; Goldhamer 외., 2020; Holmboe 외., 2017).

Similarly, the practical and atheoretical framing of CBME emphasized by many of our participants (as suggested by the key operational practices and problems CBME solves), need not equate with flawed design. It is important to remember that the traditional postgraduate medical education system in Canada was also not built on an explicit and fully integrated theoretical foundation. Rather, it borrowed practical solutions developed to address issues of quality in undergraduate medical education. The American Medical Association’s standards, reflecting the Carnegie Foundation report on North American medical schools (Flexner, 1910), was highly influential in Canada. The influence of the undergraduate medical education biomedical model on PGME has been along practical, and not theoretical, lines. In the same spirit, key opinion leaders in this study suggested a number of rationales for CBME as a practical solution for solving the current generation of problems that have developed after a century of minimal, incremental change in PGME. Significant to both the public and learners, CBME improves the accountability of residency training (Albanese et al., 2008; Goldhamer et al., 2020; Holmboe et al., 2017).

우리는 이 연구의 특정 결과의 이전 가능성은 우리의 설계 선택에 의해 필연적으로 제한된다는 점에 유의합니다. 예를 들어, 저희는 참가자 코호트를 캐나다의 저명한 이해관계자로 제한했는데, 이는 다른 관할권의 의견을 대표하지 못할 수도 있습니다. 또한 캐나다의 의대 교육자 커뮤니티가 상대적으로 작고 데이터를 익명화하려는 노력에도 불구하고 인식될 수 있다는 우려로 인해 참가자들이 개인적인 의견을 모두 공유하는 데 다소 제약을 느꼈을 수 있습니다. 따라서 이러한 다양성에도 불구하고, 이번 조사 결과는 전 세계 의학교육 담론의 근간이 되는 다양한 관점, 가정, 입장을 모두 반영하지 못했을 가능성이 높습니다. 우리의 목표는 가능한 모든 관점의 포괄적인 목록을 작성하는 것이 아니라 이러한 다양성에 대한 대화를 시작하고 다른 사람들이 자신의 사고, 계획 및 글쓰기에 이러한 고려 사항을 포함하도록 장려하는 것이었습니다.

We note that the transferability of the specific findings of this study are necessarily limited by our design choices. For example, we limited our cohort of participants to prominent stakeholders in the Canadian context, which might not be representative of the opinions from other jurisdictions. Further, our participants might have felt somewhat constrained to share the full range of their personal opinions given the relatively small community of medical educators in Canada and possible concerns of being recognized despite efforts at anonymizing the data. Thus, despite the variability seen, our findings likely under-represent the full range of lenses, assumptions and positions that underlie the discourses in the literature and the implementations of CBME across the globe. Our goal was not to create a comprehensive list of all possible perspectives, but rather to open the conversation regarding this variability and to encourage others to include such considerations in their own thinking, planning and writing.

그럼에도 불구하고 이 연구는 캐나다의 주요 오피니언 리더들 사이에서 CBME에 대한 정의가 상당히 이질적이라는 것을 보여주었습니다. 이러한 차이는 CBME 커리큘럼이 현지에서 설계되고 실행되는 방식에 차이가 있을 것으로 예상됩니다. 당연히 이는 CBME라는 공통된 레이블 아래에서 다양한 학습자 및 시스템 결과로 이어질 것입니다. 따라서 CBME의 개념화에 관한 향후 연구에서는 실행 과학에 기반하고 적절한 실행 연구 프레임워크(CFIR 연구팀-임상관리연구센터, 2021)에 근거하여 실행의 충실성(Keith et al., 2010; O'Donnell, 2008)을 탐구할 수 있습니다. 실행 과정의 영향을 이해하지 못하면 차세대 의학교육 설계자와 리더는 역량 기반 의학교육을 수정하고 개선하는 방법에 어려움을 겪을 것입니다.

Nonetheless, this study has demonstrated impressive heterogeneity in the definition of CBME among Canadian key opinion leaders. Such variance anticipates divergence in how CBME curricula are locally designed and implemented. Naturally, this will lead to varying learner and system outcomes, all under the common label of CBME. Thus, future work around the conceptualization of CBME might explore fidelity of implementation (Keith et al., 2010; O’Donnell, 2008), informed by implementation science and grounded in an appropriate implementation research framework (CFIR Research Team-Centre for Clinical Management Research, 2021). Without understanding the influence of the implementation process, the next generation of medical education designers and leaders will struggle with how to revise and refine competency based medical education.

Appendix: Interview guide

Appendix: Interview guide

CBME is a term that often gets used (and misused) in many ways. We are interested in your understanding of CBME, specific to the Canadian medical education context. In the next half hour, you will talk about three themes: the philosophies, principles and practices related to CBME.

Question 1: PHILOSOPHY

I am going to start by asking about your philosophy of CBME. By philosophy, I mean theory or conceptual framework.

- What do you believe are the philosophies that should inform CBME?

- Does your description align with what the philosophies that inform CBME curricula as developed by the Royal College or CFPC? In what ways does it differ, if at all?

- What are the core problems with the traditional medical education system that CBME is trying to solve?

- Do the philosophies that support Royal College or CFPC CBME curricula align with the problems they are trying to solve?

- Can you describe alternative educational philosophies that may better address the problems in our traditional education system?

- Why do you think they would be better?

Question 2: Principle

Now let’s talk about principles of CBME. When I refer to the principles, I mean the core components of CBME or the link between the philosophy and its application (i.e., practice). For example, a principle of PBL is self-guided study connecting the philosophy of learning by discovery with the practice of small group tutorials.

- What are the key principles underlying or supporting your philosophy of CBME?

- What principles do you think are currently missing in the current model of CBME?

- Are there assumptions built into these principles that make them susceptible to failure (e.g., sociological, cognitive and learning traits of humans)

Question 3: Practice

Finally, let’s talk about the practices that inform CBME. When I say practice, I am referring to the application or use of an idea or belief. How does an organization operationalize / make CBME principles work.

- If CBME principles were poorly enacted, what bad set of education practices would you see?

- Across learners, preceptors, and administrators?

- Recognizing that CBME will be implemented in different contexts and learning environments, what do the ideal set of practices like look? (By ideal I mean unlimited budget, no operational constraints.)

Question 4: SNOWBALL

Who else would you recommend I interview? Who are thought leaders in the design and/or scholarship of CBME?

Question 5: CONCLUSION

Lastly, is there anything else you want to share with me?

Tensions in describing competency-based medical education: a study of Canadian key opinion leaders

PMID: 33895905

Abstract

The current discourse on competency-based medical education (CBME) is confounded by a lack of agreement on definitions and philosophical assumptions. This phenomenon impacts curriculum implementation, program evaluation and disrupts dialogue with the education community. The purpose of this study is to explore how Canadian key opinion leaders describe the philosophy and practice of CBME. A purposeful and snowball sample of Canadian key opinion leaders, reflecting diversity of institutions and academic roles, was recruited. A qualitative thematic analysis of semi-structured interviews was conducted using the principles of constructivist grounded theory. A modified integrated knowledge user checking process was accomplished via a national open meeting of educators, researchers, and leaders in postgraduate medical education. Research ethics board approval was received. 17 interviews were completed between September and November 2018. 43 participants attended the open meeting. There was no unified framing or definition of CBME; perspectives were heterogenous. Most participants struggled to identify a philosophy or theory that underpinned CBME. CBME was often defined by key operational practices, including an emphasis on work-based assessments and coaching relationships between learners and supervisors. CBME was articulated as addressing problems with current training models, including failure to fail, rigor in the structure of training and maintaining the social contract with the public. The unintended consequences of CBME included a reductionist framing of competence and concern for resident wellness with changes to the learning environment. This study demonstrates a heterogeneity in defining CMBE among Canadian key opinion leaders. Future work should explore the fidelity of implementation of CBME.

Keywords: Competency-based medical education; Definitions; Medical education lexicon; Postgraduate medical education.

'Articles (Medical Education) > 평가법 (Portfolio 등)' 카테고리의 다른 글

| 사례 기반 다지선다형 문항 작성을 위한 ChatGPT 프롬프트(Spanish Journal of Medical Education, 2023) (0) | 2023.11.19 |

|---|---|

| 졸업후교육 학습자(전공의)의 평가에서 환자참여: 스코핑 리뷰(Med Educ, 2021) (0) | 2023.11.10 |

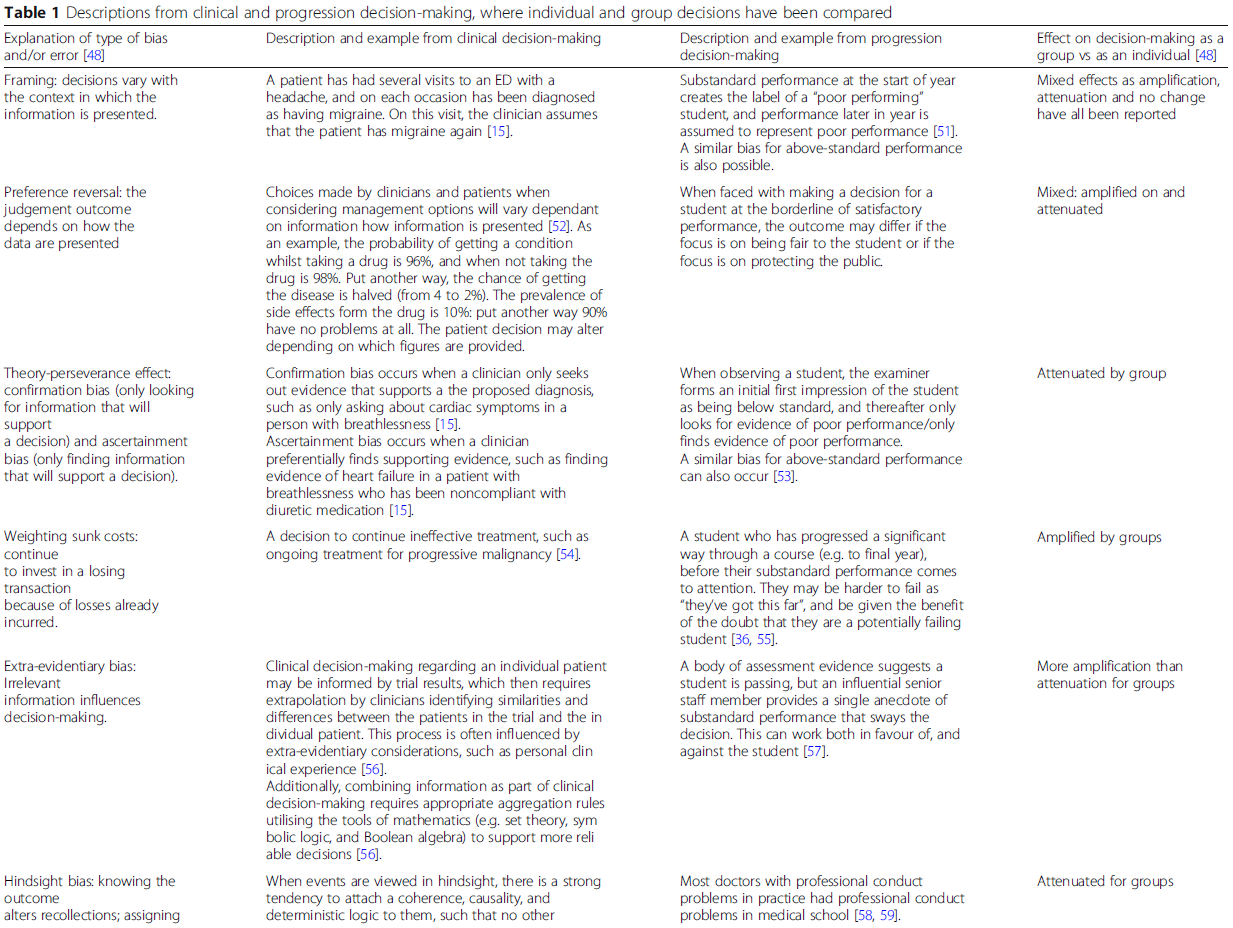

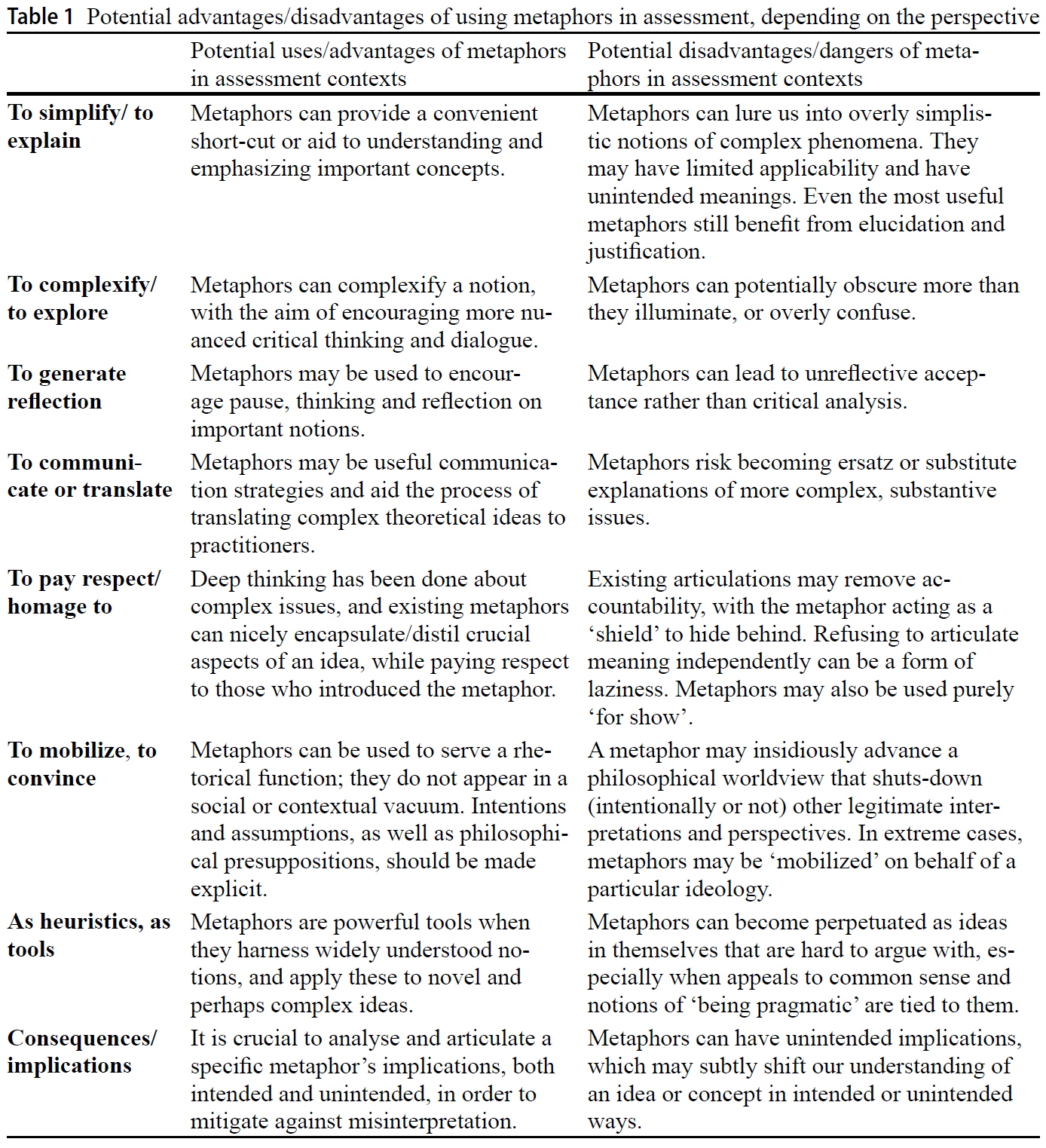

| 평가 프로그램에서 학생의 진급 결정: 임상적 의사결정과 배심원 의사결정을 외삽할 수 있을까? (BMC Med Educ, 2019) (0) | 2023.11.10 |

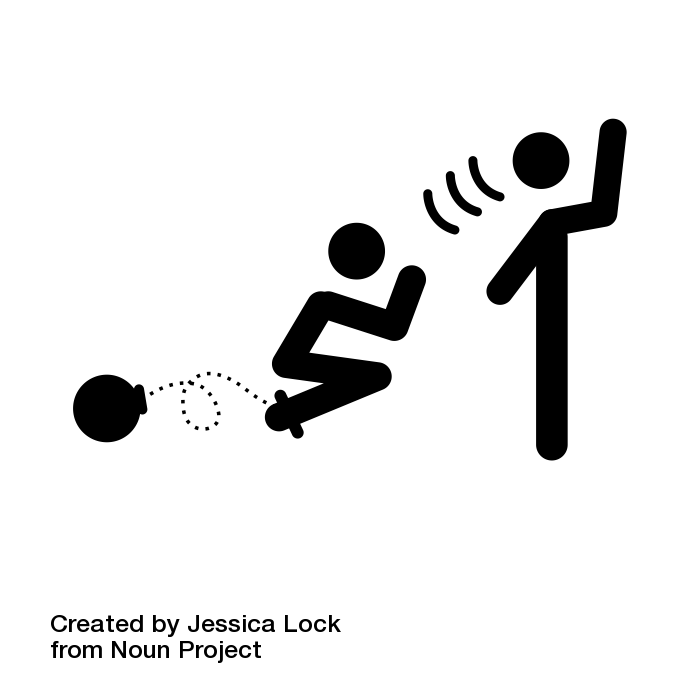

| 평가에 대한 메타포의 사용과 남용(Adv Health Sci Educ Theory Pract. 2023) (0) | 2023.11.05 |

| 사회문화적 학습이론과 학습을 위한 평가 (Med Educ, 2023) (0) | 2023.11.05 |