21세기 보건의료 시스템을 위한 교육: 기초, 임상, 시스템과학의 상호의존적 프레임워크(Acad Med, 2017)

Educating for the 21st-Century Health Care System: An Interdependent Framework of Basic, Clinical, and Systems Sciences

Jed D. Gonzalo, MD, MSc, Paul Haidet, MD, MPH, Klara K. Papp, PhD, Daniel R. Wolpaw, MD, Eileen Moser, MD, MHPE, Robin D. Wittenstein, EdD, and Terry Wolpaw, MD, MHPE

프랭크 후일러1은 그의 논평 "거울 속의 여인"에서 술에 취해 호전적이고 급성 전심근경색을 앓고 있는 노숙자, 정신분열증 환자, 병적으로 비만인 여성과의 만남을 묘사하고 있다. 몇 주 전에 놓여진 스텐트는 주로 응고를 막는 비싸지만 중요한 약물이 없었기 때문에 응고되었다. 약을 공짜로 얻을 수 있는 준비에도 불구하고, 환자는 그것을 가지러 가는 버스비를 관리할 수 없었다.

In his Commentary “The Woman in the Mirror,” Frank Huyler1 describes his encounter with a homeless, schizophrenic, morbidly obese woman who presents to the emergency department drunk, belligerent, and suffering an acute anterior myocardial infarction. A stent placed several weeks earlier had clotted, due mainly to the absence of an expensive but important medication that prevents clotting. Despite arrangements to obtain the medication for free, the patient could not manage bus fare to pick it up.

몇 주 동안 병원에 입원한 후, 그리고 수십만 달러를 쓴 후에, 그녀는 살아남았습니다. 그리고 나서 그녀는 거리로 다시 퇴원했다. 어디서부터 시작할까요? 그건 알기 어렵다. 우리는 사회가 정신병을 어떻게 보고 치료하는지 살펴보는 것으로 시작하나요? 정신분열증 환자, 알코올 중독자, 길거리 사람들에게 스텐트를 주입한 심장병 전문의의 지혜에 의문을 품기 시작할까요? 터무니없이 비싼 약의 준수가 매우 중요할 수 있다는 것을 알면서 말이죠. 만약 심장전문의가 스텐트를 삽입하지 않았다면, 우리는 치료 기준을 제공하지 못한 그나 그녀를 탓할 수 있을까요? 환자에게 주거비와 식비를 제공하는 것을 고려하지 않는데 왜 우리는 스텐트에 7천 달러를 지출하는가?1

After weeks in the hospital and after many hundreds of thousands of dollars were spent, she survived. Then she was discharged back to the street…. Where to start? It’s hard to know. Do we start with examining how society views and treats the mentally ill? Do we start questioning the wisdom of the cardiologist who put a stent into a schizophrenic, alcoholic street person, knowing that compliance with an outrageously overpriced medication would then be vitally important? If the cardiologist had not put in the stent, would we fault him or her for failing to provide the standard of care? Why do we spend $7,000 on a stent, when we do not consider providing the patient with housing and food [or bus fare]?1

Huyler 박사는 의학과 의학교육에서 인문학이 차지하는 역할에 대해 쓰고 있었지만, 버스 이용권만 있으면 되는 환자를 구하기 위해 기술적으로 진보된 카테터화 실험실과 고도로 훈련된 전문가들을 활성화할 수 있는 미국의 의료 시스템에 대해 쓰고 있었을 수도 있다. 고비용이지만, 분절되어있고, 성능이 낮은 미국의 의료 시스템에 대한 증거는 새로운 것이 아니다.2 이러한 비효율성을 해결하기 위해, 경제적인 관리법과 같은 정책들은 의료 시스템이 대응, 재구성 및 통합하도록 유도하고 있으며, 이는 과거와는 근본적으로 다른 의료행위를 할 환경을 조성하고 있습니다.

Dr. Huyler was writing about the role of the humanities in medicine and medical education, but could have been writing about the U.S. health care system, capable of activating a technologically advanced catheterization laboratory and highly trained specialists to save a patient who really only needed a bus voucher. The evidence for a high-cost, fragmented, and low-performing U.S. health care system is not new.2 To address these insufficiencies, policies such as the Affordable Care Act are prompting health care systems to react, reorganize, and consolidate, creating a practice environment fundamentally different from that of the past.

추세는 개인 의사에서 전문 팀 간 진료로 전환되고 있습니다.3 의료 결과는 개별 환자 건강에서 [환자의 경험 개선, 인구 건강 증진, 비용 절감]이라는 "3중 목표"로 진화하고 있습니다.4 전자 의료 기록, 데이터 관리 시스템 및 결제 시스템이 발전함에 따라 의료는 개인 환자에만 초점을 맞추기보다는 인구에 대한 질병의 사전 예방적 관리에 점점 더 초점을 맞출 것이다. 의료 분야의 이러한 새로운 방향은 의사의 전통적인 역할 기대치에 대한 근본적인 패러다임 변화를 나타낸다. 하지만, 우리의 교육은 여전히 동맥경화의 병리생리학 및 관상동맥질환의 치료에 집중되어 있다. 뭔가 빠져있다. 학습자에게 환자 경험 또는 시스템 과학에 대한 병렬 참여를 제공하는 곳은 어디입니까?

Trends are shifting away from the solo practitioner to care delivered by interprofessional teams.3 Health care outcomes are evolving from individual patient health to the Institute for Healthcare Improvement’s “triple aim” of improving patients’ experiences, promoting population health, and reducing cost.4 With the advancement of electronic medical records, data management systems, and payment systems changes, health care will increasingly focus on proactive management of disease for populations, rather than focusing solely on individual patients. These new directions in health care represent fundamental paradigm shifts for the traditional role expectations of physicians. However, our education remains focused (as in Dr. Huyler’s story) on learning the pathophysiology of atherosclerosis and treatment of coronary artery disease. Something is missing. Where are we providing learners with parallel engagement in the patient experience or systems sciences?

2013년 캐서린 루시5는 의학 교육의 재검토와 "시스템 과학"의 의학 커리큘럼의 통합을 요구했다.

- 어디서부터 시작할까요?

- 우리가 전통적인 과학과 함께 핵심 교육 노력에 시스템 교육을 배치한다면 어떨까요?

- 만약 우리가 닥터 후일러처럼 환자들의 질병을 이해할 수 있는 도구를 제공한다면 어떨까요? 그리고 나서 학생들이 이러한 환자들과 함께 치료 장벽을 식별하고 해결할 수 있는 기회를 만들면 어떨까?

In her seminal challenge in 2013, Catherine Lucey5 called for a reexami nation of medical education and incorporation of “systems sciences” into the medical curriculum.

- Where to start?

- What if we located systems education in core educational efforts alongside traditional sciences?

- What if we provided the tools to understand the diseases of patients like Dr. Huyler’s and then created opportunities for students to work with these patients to identify and address barriers to care?

의학교육의 3축 기본틀

The Three-Pillar Framework of Medical Education

플렉스너 보고서 이후, 대부분의 의과대학들은 기초과학에서 학생들을 먼저 교육했고, 그 다음에는 임상과학에서 교육을 받았다. 6,7 비록 많은 학교들이 초기 임상과학의 기회를 만들고, 나중에 기초과학에 다시 방문함으로써 이 전통적인 틀에 도전했지만, 교육의 일반적인 체계는 여전히 이것에 기초하고 있다.

Since the Flexner report, most medical schools have educated students first in the basic sciences, then in the clinical sciences.6,7 Although many schools have challenged this traditional framework by creating early clinical science opportunities and revisiting basic sciences during later years, the general system of education is still based on this dyad.

동시에, 미래의 의사들이 복잡한 의료 시스템에서 일하려면, 다음과 관련된 지식과 능력이 필요하다는 것이 점점 더 인정되고 있다 - 의료 금융, 인구 건강, 질 향상, 사회 생태학적 건강, 정보학자, 팀워크, 리더십 및 의료 전달 과학과 관련된 기타 영역. 이러한 시스템 과학은 학문 간 융합이 높고 전통적인 기초(예: 생리학, 생화학) 또는 임상(예: 소아과, 수술) 과학과는 구별되므로 혁신적이고 통합된 교육학적 전략과 교육 프레임워크에 대한 새로운 비전이 필요한 변화가 필요하다.

Concurrently, it is increasingly recognized that for future physicians to work in complex health care systems, they will need to have knowledge and abilities related to health care financing, population health, quality improvement, socio-ecological health, informatics, teamwork, leadership, and other areas related to the science of health care delivery.5,8,9 These systems sciences are highly interdisciplinary and distinct from either traditional basic (e.g., physiology, biochemistry) or clinical (e.g., pediatrics, surgery) sciences, necessitating changes that require innovative and integrated pedagogical strategies and a fresh vision for our educational framework.

우리는 의료 시스템의 증가하는 복잡성을 이해하고 탐색하는 데 시스템 지식과 기술에 대한 숙련도가 점점 더 중요해지고 있기 때문에, 의학교육은 [진화하는 의료 시스템의 요구에 부합하고 시스템 과학 역량을 개발할 기회]를 학생들에게 제공해야 한다고 생각한다. 이러한 변환은 기본 및 임상 과학의 전통적인 2필러 관계를 기본, 임상 및 시스템 과학의 상호의존적 3필러 프레임워크로 재구성할 것이다.

We believe medical education must align with the needs of the evolving health care system and provide students with opportunities to develop systems science competencies, since proficiency in systems knowledge and skills has become increasingly important to understanding and navigating the growing complexity of the health care system. This transformation will reframe the traditional two-pillar relationship of basic and clinical sciences to an interdependent three-pillar framework of basic, clinical, and systems sciences.5,9

일부 교육 프로그램이 현재 커리큘럼에 시스템 기반 주제를 포함하지만, 그것들은 유한하고 고립되어 있으며 커리큘럼 개혁에 명시적으로 통합된 초점이 아니다. 우리는 의과대학이 기초 및 임상 과학에 전념하는 보조 또는 준-수준의 학장 직위를 가지고 있지만, 3개 기둥 프레임워크로 전환하려면, [시스템 과학의 설계와 커리큘럼 통합에 전념할 수 있도록], 시스템 과학에서 (부)학장급 직위가 필요할 것이라고 제안한다.

Although some education programs now include systems-based topics in the curriculum, they are finite, isolated, and not an explicitly integrated focus of curriculum reform.10,11 We suggest that although medical schools have assistant- or associate-level dean positions dedicated to basic and clinical sciences, the shift to a three-pillar framework would require similar dean-level positions in systems sciences dedicated to the design and integration of these systems sciences into the curriculum.

또한 성공적인 통합을 위해 이러한 시스템 과학을 포함하도록 인지 및 커리큘럼 공간의 균형 조정이 필요하다. 현재, 기초의학과 임상의학 학습은 다양한 의사 경험에서 맥락화된다. 3축 프레임워크로 전환하려면 시스템 과학을 교실 밖에서 적용할 수 있는 기회를 만들어야 할 것이다. 요컨대, 3개 필러 모델 하에서 시스템 과학은 임상 및 기초 과학과 동일한 중요도, 집중도 및 주의를 제공받게 될 것이다.

Additionally, a rebalancing of cognitive and curriculum space to include these systems sciences is required to allow for successful integration. Currently, basic and clinical science learning are contextualized in a variety of doctoring experiences. The shift to a three-pillar framework would require the creation of opportunities to also apply systems sciences outside of the classroom. In short, under the three-pillar model the systems sciences would be offered with the same importance, focus, and attention as the clinical and basic sciences.

과감한 변화는 쉽게 찾아오지 않으며 가볍게 여겨지지 않는다. 과감한 변화는 쉽게 찾아오지 않으며 가볍게 여겨지지 않는다. 세 개의 기둥으로 구성된 프레임워크는 학교의 교육 프로그램의 목표와 목표에 대한 집중적이고 비판적인 검토가 필요하다.

- 이미 과부하가 걸린 커리큘럼에 내용을 추가할 수 없습니다. 교육자들은 전통적인 강의실의 역할과 많은 양의 사실 습득의 필요성에 대한 근본적인 질문들과 씨름할 필요가 있는데, 이 때 학생들은 궁극적으로 보건 정보학자와 진료 시점 자원을 급속히 확장하는 시대에 연습을 하게 될 것이다.

- 우리는 더 큰 대중의 이익에 부합하는 전체를 만들기 위해 전체 커리큘럼에 걸쳐 잘 검증된 학습 원칙을 결합할 필요가 있다.8

- 또한, 보드 시험과 전공의 요구사항에 시스템 과학이 상대적으로 덜 표현되고 있는 것도 학생들을 이 새로운 학습 의제에 참여시키는 데 상당한 장벽을 만든다.

Bold changes do not come easily and are not to be taken lightly. A three-pillar framework necessitates an intensive, critical review of the goals and objectives of a school’s educational program.

- Adding content to an already-overloaded curriculum will not work. Educators need to grapple with fundamental questions about the role of the traditional classroom and the need for large volumes of fact acquisition, when the students will ultimately be practicing in an era of rapidly expanding health informatics and point-of-care resources.12,13

- We need to combine well-validated learning principles across the entire curriculum to create a whole that aligns with greater public interest.8

- Additionally, the relative lack of representation of systems sciences on board examinations and in residency expectations creates significant barriers to engage students in this new learning agenda.

이러한 과제는 3축 모델을 구현하기 전과 구현하는 동안 해결되어야 한다.14 사회적 요구를 지속적으로 예측하는 적응형 교육 시스템을 원한다면 세 가지 요소를 모두 새로운 시각으로 참여시키고 연결해야 한다.

These challenges must be addressed prior to and during implementation of a three-pillar model.14 If we want adaptive educational systems that continuously anticipate societal needs, we need to engage and connect all three pillars with fresh eyes.

3축 교육체계 내 시스템 커리큘럼

A Systems Curriculum Within a Three-Pillar Education Framework

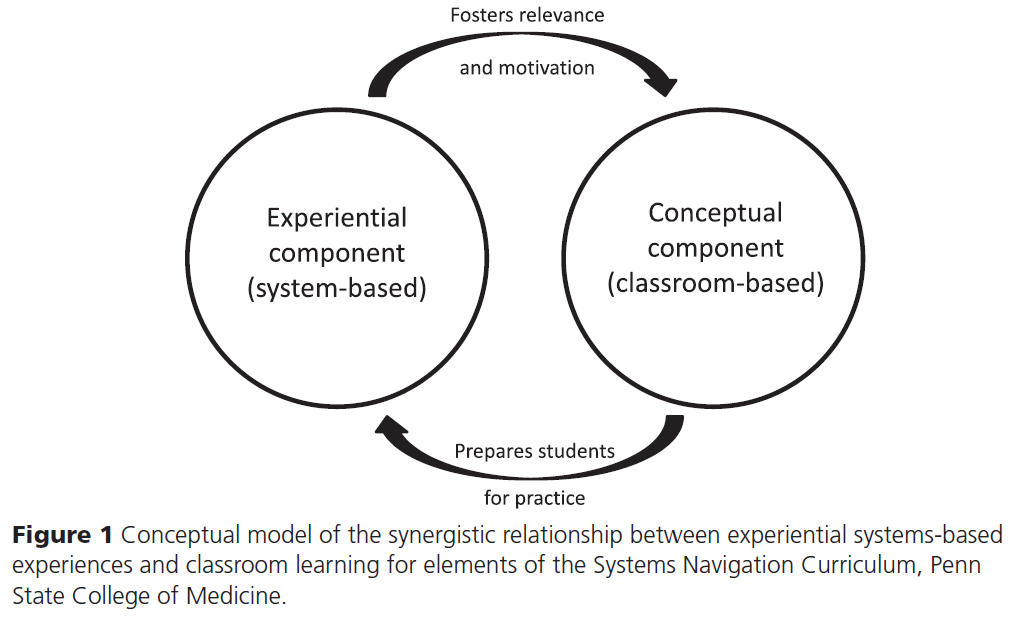

우리는 기초 과학 및 임상 과학과 상호 독립적으로 작동하는 3개 필러 교육 프레임워크에 포함된 시스템 커리큘럼 모델을 제시한다. 이 시스템 커리큘럼은 두 가지 교육학적 구성요소, 즉 강의실 기반 개념 구성요소와 보건 시스템 기반 경험 구성요소로 구성된다. 개념적 및 경험적 구성요소는 동시에 상호 강화되도록 설계되었다(그림 1).

- [개념적 요소]에서 학생들은 시스템 과학을 사용하여 조직, 지역사회 및 소셜 네트워크에서 의료 제공과 관련된 문제에 대해 배우고 씨름하며 시스템 기반 역할의 실천을 준비한다.

- [경험적 요소]에서 학생들은 시스템 개념을 사용하여 의료 시스템 전반의 실제 환경에서 환자 치료를 개선하는 연습을 할 것이다. 이 경험 기반 구성요소는 시스템 과학의 기본 개념 학습과 그러한 학습의 동기 부여에 대한 학생들의 관련성에 대한 인식을 강화해야 한다. 두 요소 모두 학생들이 그들 사이의 연결을 발견할 수 있도록 설계되어야 하며, 결과적으로 다른 요소에 참여함으로써 그들의 학습을 강화해야 한다.

We present a model for a systems curriculum embedded within a three-pillar educational framework that functions interdependently with the basic and clinical sciences. This systems curriculum has two pedagogical components: a classroom-based conceptual component and a health-system-based experiential component. The conceptual and experiential components are designed to be simultaneous and mutually reinforcing (Figure 1).

- In the conceptual component, students would learn about and wrestle with issues relevant to health care delivery in organizations, communities, and social networks using the systems sciences, preparing them for practice in systems-based roles.

- In the experiential component, students would practice using systems concepts to improve patient care in real-world environments across the health care system. This experience-based component should foster students’ awareness of the relevance for learning the fundamental concepts of systems sciences, as well as motivation for such learning.15 Both components should be designed so that students can discover connections between them, subsequently reinforcing their learning in one by participating in the other.

여러 저자가 의료 조정, 환자 안전 및 품질 개선 방법, 팀워크를 포함한 [개념적 요소]에 적합한 콘텐츠를 제안했습니다.10,11 개념이 제안되고 일부는 구현되었지만, 강력한 [경험적 요소]를 공유하는 방법에 대한 논의는 상대적으로 적습니다.5,9–11 다양한 반면 활동이 적절할 수 있으므로, [이상적인 경험적 요소]는 다음 세 가지 기준을 충족시킬 것을 제안한다.

- 진정한authentic 실무 경험을 얻을 수 있습니다.

- 핵심 시스템 기반 실무 개념을 직접 경험할 수 있도록 지원합니다.

- 학생들이 그 안에서 치료를 받는 환자의 눈을 통해 시스템을 볼 수 있게 할 것이다.

Several authors have suggested content suitable for the conceptual component, including care coordination, patient safety and quality improvement methods, and teamwork.10,11 Although concepts have been proposed and some implemented, there is comparatively little discussion about the way to share a robust experiential component.5,9–11 While various activities may be appropriate, we suggest that the ideal experiential component will fulfill three criteria:

- It will allow for an authentic practice experience;

- It will allow direct experience with core systems-based practice concepts; and

- It will allow students to view the system through the eyes of the patients receiving care within it.

첫째, [진정한authentic 실천 경험]은 학생들이 경험과 개념적 요소 모두에 참여하려는 동기를 강화시키기 때문에 중요하다.15,16 의료 시스템에서 필수적인 역할을 수행하는 학생들은 두 커리큘럼 요소에 진지하게 참여할 가능성이 더 높다.

First, authentic practice experiences are critical, as they enhance students’ motivation to participate in both the experiential and conceptual components.15,16 Students performing essential roles in the health care system are more likely to seriously engage in both curriculum components.

둘째, [시간적으로 정렬된 직접 경험]은 [학습한 시스템 기반 개념]을 [실제 실행]으로 전이하는 것을 고정하고 강화하는 데 도움이 될 것이다. 이러한 커리큘럼 강화는 학생들이 미래의 임상 실습에 학습된 교훈을 적용하고, 21세기 실습에 필요한 시스템 사고 관점을 채택할 가능성이 높은 의사 양성으로 이어질 수 있다.17

Second, temporally aligned direct experience will help to anchor and enhance transfer of learned systems-based concepts to real-world practice. Such curricular reinforcement may lead to students applying lessons learned to future clinical practice, as well as cultivation of physicians more likely to adopt the systems-thinking perspectives needed for 21st-century practice.17

마지막으로, [환자의 눈을 통해 시스템을 보는 것]은 학생들이 [의료서비스가 제공될 그 모집단]과 연결된 상태를 유지하도록 돕는다. 학생들은 의료 시스템의 미래 실무자, 지도자, 설계자이기 때문에, 우리는 환자의 경험에 기초한 교육이 환자의 요구에 더 부합하는 시스템의 개발을 이끌 것이라고 믿는다.

Finally, seeing the system through patients’ eyes helps students remain connected to the very populations health care systems are created to serve. Because students are the future practitioners, leaders, and designers of health care systems, we believe an education grounded in patients’ experiences will lead to the development of systems more aligned with patients’ needs.

닥터 Huyler 환자의 사례로 돌아오면, 전통적인 의대생 역할은 복잡한 카테터 실험 활동과 후속 병원 진료, 급성 심근경색 및 스텐트 관리에 대한 사례 회의를 관찰하는 것을 포함할 수 있다. 하지만 이것들이 중요한 학생-의사 학습 경험일지라도, 학생들은 이러한 의료전달 과정에서 "교육적인 방관자"이기 때문에 진정한 의미의 참여형 의료 역할로 적격하지는 않다. 더 확장된 렌즈를 사용하여, 미래의 의사가 어떤 기술을 필요로 하는지 본다면, 환자에게는 "고부담"으로 인식되는 전통적인 의사 중심적 기술을 필요로 하지 않는다는 것을 알게 된다.

Returning to Dr. Huyler’s patient, the traditional medical student role might have involved observing complex catheterization lab activities and subsequent hospital care, and case conferences on acute myocardial infarctions and stent management. These can be important student–doctor learning experiences, but they do not qualify as authentic, engaged health care roles because students are “educational bystanders” in care delivery processes. Using the expanded lens to view the skills required of future physicians, we see that patients frequently do not require traditional physician-centric skills, which are perceived as “higher stakes.”9,15,18–20

오히려, 환자들은 "돌봄"을 필요로 하며, 이것은 생물의학으로 분류되기보다는, 사회 또는 시스템 문제로 더 광범위하게 분류된다.21 보건 시스템 내의 초기 심층 중심 경험은 학생들이 진정한 의미 있는 직장 역할에 참여할 수 있는 높은 활용 영역을 제공한다. 우리는 환자 탐색patient navigation이 전통적인 임상 경험과 유사하고 향상된 방식으로 시스템 기반 환자 관리를 제공하는 참여적인 역할을 학생들에게 제공한다고 믿는다.

Rather, patients require “care” in areas not labeled as biomedicine, but classified more broadly into social or systems issues.21 Early depth-focused experiences within health systems provide a high-leverage area for student participation in authentic, meaningful workplace roles. We believe that patient navigation provides students with a participatory role in providing systems-based patient care in a way that parallels and enhances traditional clinical experiences.

진정한 시스템 과학 역할로서의 환자 탐색

Patient Navigation as an Authentic Systems Science Role

학생 운영 무료 진료소, 응급 의료 기술자 교육, 종적 통합 임상실습 등과 같은 의료 시스템에 대한 학생 참여에 대한 문헌이 증가하고 있다. 9,19,20 이러한 기회가 시스템 과학 학습과 연계될 수 있지만, [환자 탐색]의 역할이 [시스템 커리큘럼의 경험적 요소]로서 훌륭한 후보라고 생각한다. 1990년에 처음 구현된 환자 탐색은 의료 제공의 격차를 해소하고 환자와 시스템 기반 장벽을 극복하며 진단/치료의 지연을 줄이고 결과를 개선하는 데 도움이 되는 전략이다.22-24

There is a growing literature on student participation in health care systems such as student-run free clinics, emergency medical technician training, and longitudinal integrated clerkships.9,19,20 Although these opportunities could be linked to systems sciences learning, we believe the role of patient navigation is an excellent candidate for the experiential component of a systems curriculum. First implemented in 1990, patient navigation is a strategy that helps bridge gaps in health care delivery, overcome patient and systems-based barriers, reduce delays in diagnosis/treatment, and improve outcomes.22–24

[환자 탐색Patient navigation]은 [외부지원 인력outreach worker]을 사용하여 환자가 복잡한 시스템을 통해 기동하여 더 나은 치료를 받을 수 있도록 돕는다. 조직과 지역사회에서 환자 및 제공자와 함께 일하는 환자 네비게이터는 환자를 자원에 연결하고, 환자를 치료 계획 완료에 보조하며, 환자에게 의료 문제에 대해 교육하고, 치료 장애물을 식별하고 제거한다.

Patient navigation uses outreach workers to help patients maneuver through complex systems to obtain better care. Working with patients and providers in the organization and community, patient navigators connect patients to resources, assist patients in completing care plans, educate patients about medical issues, and/or identify and remove impediments to care.25,26

학생들이 [환자 네비게이터] 역할을 할 수 있는 기회를 만드는 것은 이상적인 체험 활동에 대한 세 가지 기준을 충족합니다.

- 첫째, 많은 의료 시스템이 이러한 부가적인 역할이 부족하거나 필요한 상태이며, 학생들은 그들의 진정한 실천 경험을 통해 의미 있는 기여를 할 수 있는 위치에 있다.

- 둘째, 환자 탐색을 통해 학생들은 접근, 재정 지원, 커뮤니티 기반 서비스 및 시스템 비효율성을 포함한 많은 시스템 개념과 직접 접촉할 수 있습니다.

- 셋째, 환자 탐색은 본질적으로 환자 중심이며, 환자의 사회적 맥락과 관점을 이해해야 한다.

- 마지막으로, 환자 네비게이션의 많은 모델이 일반 직원이 네비게이터로서 효과적으로 기능할 수 있다는 것을 입증했기 때문에, 학생들은 장기간 훈련 없이 의대에서 일찍 그 직무를 수행할 수 있다.18

Creating opportunities for students to serve as patient navigators fulfills the three criteria for an ideal experiential activity.

- First, many health care systems either lack or are in need of this value-added role, and students are positioned to make meaningful contributions through their authentic practice experiences.

- Second, patient navigation brings students into direct contact with many systems concepts, including access, financing, community-based services, and systems inefficiencies.

- Third, patient navigation is inherently patient centered, requiring an understanding of patients’ social contexts and perspectives.

- Finally, since many models of patient navigation have demonstrated that lay personnel can function effectively as navigators, students can perform navigator duties early in medical school without prolonged training.18

시스템 기반 커리큘럼의 예: 펜실베이니아 주립 의과대학 내비게이션 교육과정

An Example of a Systems-Based Curriculum: The Pennsylvania State University College of Medicine Systems Navigation Curriculum

2014년 가을, 우리는 펜실베이니아 주립 의과대학(PSUCOM)의 모든 의대 학생들을 위한 새로운 커리큘럼, 즉 시스템 네비게이션 커리큘럼(Sync)을 개발하고 시행했다. 이 커리큘럼은 (1) 건강 시스템 과학 과정 및 (2) 환자 탐색기 경험 등 개념적 및 경험적 구성요소로 구성된다. 이 두 가지 구성 요소는 우리 학생들의 의대 첫 2년 동안 주당 평균 3~4시간을 포함합니다. 과정(개념 구성요소)과 탐색 경험(경험적 구성요소) 모두 학생들이 진화하는 의료 시스템의 복잡성 속에서 효과적으로 기능할 수 있는 지식, 태도 및 기술을 개발할 수 있도록 한다. SyNC의 목표는 다음과 같습니다.

- 심리적, 사회적, 시스템 기반 요소를 포함하여 의료에 대한 전체적인 접근 방식을 시연합니다.

- 인구 및 환자 중심의 관리를 기술하고 전달한다.

- 의료 및 지역사회 기반 전문가 팀의 효과적인 구성원으로 참여

- 사후 대응적 사고와 의사 결정이 아닌 사전 예방적 의사 결정 능력을 입증

- 의료에서 가치 기반 의사 결정을 내립니다.

In the fall of 2014, we developed and implemented a new curriculum for all medical students at the Pennsylvania State University College of Medicine (PSUCOM)—namely, the Systems Navigation Curriculum (SyNC). This curriculum consists of conceptual and experiential components: (1) the Science of Health Systems Course, and (2) patient navigator experiences. In total, these two components involve an average of three to four hours per week in our students’ first two years of medical school. Both the course (conceptual component) and navigation experiences (experiential component) allow students to develop the knowledge, attitudes, and skills to function effectively amid the complexities of an evolving health care system. SyNC’s goals are that students:

- Demonstrate a holistic approach to health care, including psychological, social, and systems-based elements;

- Describe and deliver population- and patient-centered care;

- Participate as effective members of medical and community-based interprofessional teams;

- Demonstrate proactive rather than reactive thinking and decision making; and

- Make value-based decisions in medical care.

건강 시스템 과학 과정은 학생들이 학부 생활을 한 첫 17개월 동안 진행되며, 기초 및 임상 과학 과정과 동시에 진행됩니다. 학생들은 재정, 인구 및 공공 보건, 사회 생태 의학, 고부가가치 의료, 팀워크, 리더십, 증거 기반 의학 등 의료 전달 과학의 개념을 배운다(차트 1). 또한 의료 시스템 내에서 환자 네비게이터 역할에서 이러한 개념을 동시에 적용합니다.

The Science of Health Systems Course spans the first 17 months of the students’ undergraduate experience and is simultaneous with course work in basic and clinical sciences. Students learn concepts of the science of health care delivery, including financing, population and public health, socio-ecological medicine, high-value care, teamwork, leadership, and evidence-based medicine (Chart 1). They simultaneously apply these concepts in their roles as patient navigators within the health care system.

프로그램 시작 1년 전, 우리는 펜실베이니아 주 남부에서 환자 네비게이션 사이트 네트워크 개발에 착수했습니다. 우리는 환자 중심의 의료 가정, 입원 환자 퇴원 프로그램, 수술 체중 감소 프로그램, 국영 결핵 클리닉 등 광범위한 임상 현장을 갖춘 여러 건강 시스템과 제휴했다. 우리는 환자 네비게이션이 필요한 환자 모집단을 식별할 수 있는 임상 사이트를 식별했으며 지속 가능한 네트워크를 구축하기 위해 PSUCOM과 기꺼이 협력했다. 네트워크의 환자 모집단에는 다양한 문제와 환자 유형이 포함된다. 예를 들어, 여러 사이트에는 초유틸리티(superutilizer)로 간주되는 환자(즉, 병원 재입원이 빈번한 환자)에 초점을 맞추고 있다.27,28

The year prior to the launch of the program, we embarked on developing a network of patient navigator sites in south central Pennsylvania. We partnered with several health systems with a wide range of clinical sites, including patient-centered medical homes, inpatient discharge programs, a surgical weight loss program, and a state-run tuberculosis clinic, among others. We identified clinical sites that could identify a patient population in need of patient navigation and were willing to collaborate with PSUCOM to build a sustainable network. Patient populations in the network include a spectrum of issues and patient types. For example, several sites include a focus on patients considered to be superutilizers—that is, those with frequent hospital readmissions.27,28

모든 설정에서 학생들은 비의학적인 역할로 활동하는 [Interprofessional 의료진]에 포함되고, 현장 멘토(예: 환자 네비게이터, 관리 코디네이터)와 연계되어 1년 동안 환자 네비게이터 활동을 통해 학생들을 안내한다. 학생들이 동시 건강 시스템 과학 강좌로 돌아오면, 그들은 서로 다른 임상 사이트에 걸쳐 이질적인 경험을 가진 학생들로 구성된 소규모 그룹 "SynC 팀"에서 일한다.

In all settings, students are embedded into interprofessional clinical teams functioning in a nonphysician role and linked with site mentors (e.g., patient navigator, care coordinator) to guide them through patient navigator activities for the duration of one academic year. When students return to the concurrent Science of Health Systems Course, they work in small-group “SyNC Teams” composed of students with heterogeneous experiences across different clinical sites.

이러한 경험의 혼합은 환자 중심 문제에 대한 풍부한 성찰과 토론을 가능하게 하여 팀의 논의 범위를 넓힌다. 또한 우리는 의료팀의 소중한 구성원으로 일하고, 의사의 역할을 비의학적 관점에서 볼 수 있는 기회가 주어진다면, 우리 학생들은 의미 있는 협업과 대안적 관점에 대한 이해를 포함하는 전문적인 정체성을 개발할 것이라고 믿는다. 학생들은 그들이 탐색하는 것을 돕는 환자들을 위해 운동하는 동안 그들의 생물의학, 임상 및 시스템 연구의 상호의존성을 직접 볼 수 있는 기회를 가진다.

This intermixing of experiences allows for enriched reflections and discussions about patient-centered issues, expanding the breadth of teams’ discussions. We also believe that given the opportunity to work as a valued member of a health care team and view the role of the doctor from a nonphysician perspective, our students will develop professional identities that incorporate an understanding of meaningful collaboration and alternative perspectives. Students have the opportunity to see firsthand the interdependence of their biomedical, clinical, and systems studies as they play out for the patients they help navigate.

SynNC는 원래 의과대학 교육 프로그램으로 설계했지만, [3개 필러 프레임워크]가 보건 전문가 교육 프로그램에 걸쳐 적용될 것을 제안한다. 간호, 간호사 개업의, 약국, PA 프로그램을 포함한 많은 전문 프로그램들이 시스템 교육을 커리큘럼에 통합하기 시작하고 있다.

Although we designed SyNC for our undergraduate medical education program, we propose that the three-pillar framework is applicable across health professions educational programs. Many professional programs, including nursing, nurse practitioner, pharmacy, and physician assistant (PA) programs, are beginning to incorporate systems education into their curricula.

결론 Conclusion

[시스템 실패]는 "거울 속의 여자"에서 묘사된 것만큼 항상 극적인 것은 아니지만, 비슷한 이야기들이 우리의 건강 관리 시스템 전체에 걸쳐 수없이 실망스러운 방식으로 작용한다. 정부 및 의료 기관들은 이러한 노력이 종종 불균일하고 잠정적이긴 하지만, 집중력의 격차와 이를 가능하게 하는 잘못된 자원 배분을 해결하기 시작했다. 의학교육계는 문제점을 인식했지만 교육계획과 전략의 적응적 변화는 더디게 진행되고 있다. 기초과학과 임상과학의 전통적인 두 개의 기둥으로 이루어진 교육과정에는 단순하게 일을 하기에는 너무 많은 짐이 있다. 우리는 의료의 설계와 조직에 급속한 변화가 일어나고 있는 것을 고려할 때, 의료 교육 역시 빠르게 진화할 필요가 있다고 제안한다. 두 개의 기둥으로 된 교육과정을 [기초, 임상, 시스템 과학]의 [새로운 3개의 기둥]으로 바꿈으로써 21세기에 의사들을 더 잘 준비시킬 것이다.

Systems failures are not always as dramatic as that described in “The woman in the mirror,” but similar stories play out in myriad frustrating ways throughout our health care system. Governmental and health care organizations have begun to address the gaps in focus and the misdirected resource allocations that allow this to happen, though these efforts are frequently uneven and tentative. The medical education community has recognized the problem, but adaptive changes in educational planning and strategies have been slow. There is simply too much baggage in the traditional two-pillar curriculum of basic and clinical sciences for simple adjustments to work. We suggest that, given the rapid changes taking place in the design and organization of health care, medical education too needs to evolve rapidly. The shift from the two-pillar curriculum to a new three-pillar triad of basic, clinical, and systems sciences will better prepare physicians for practice in the 21st century.

Acad Med. 2017 Jan;92(1):35-39.

doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000000951.

Educating for the 21st-Century Health Care System: An Interdependent Framework of Basic, Clinical, and Systems Sciences

Jed D Gonzalo 1, Paul Haidet, Klara K Papp, Daniel R Wolpaw, Eileen Moser, Robin D Wittenstein, Terry Wolpaw

Affiliations collapse

Affiliation

- 1J.D. Gonzalo is assistant professor of medicine and public health sciences and associate dean for health systems education, Penn State College of Medicine, Hershey, Pennsylvania. P. Haidet is professor of medicine, humanities, and public health sciences and director of medical education research, Penn State College of Medicine, Hershey, Pennsylvania. K.K. Papp is adjunct professor of medicine, Pennsylvania State University College of Medicine, Hershey, Pennsylvania. D.R. Wolpaw is professor of medicine and humanities, vice chair for educational affairs, Department of Medicine, and director, Kienle Center for Humanistic Medicine, Penn State College of Medicine, Hershey, Pennsylvania. E. Moser is associate professor of medicine and associate dean for medical education, Penn State College of Medicine, Hershey, Pennsylvania. R.D. Wittenstein is assistant professor of public health sciences, Penn State College of Medicine, and chief operating officer, Penn State Hershey Health System, Hershey, Pennsylvania. T. Wolpaw is professor of medicine and vice dean for educational affairs, Penn State College of Medicine, Hershey, Pennsylvania.

- PMID: 26488568

- DOI: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000000951Abstract

- In the face of a fragmented and poorly performing health care delivery system, medical education in the United States is poised for disruption. Despite broad-based recommendations to better align physician training with societal needs, adaptive change has been slow. Traditionally, medical education has focused on the basic and clinical sciences, largely removed from the newer systems sciences such as population health, policy, financing, health care delivery, and teamwork. In this article, authors examine the current state of medical education with respect to systems sciences and propose a new framework for educating physicians in adapting to and practicing in systems-based environments. Specifically, the authors propose an educational shift from a two-pillar framework to a three-pillar framework where basic, clinical, and systems sciences are interdependent. In this new three-pillar framework, students not only learn the interconnectivity in the basic, clinical, and systems sciences but also uncover relevance and meaning in their education through authentic, value-added, and patient-centered roles as navigators within the health care system. Authors describe the Systems Navigation Curriculum, currently implemented for all students at the Penn State College of Medicine, as an example of this three-pillar educational model. Simple adjustments, such as including occasional systems topics in medical curriculum, will not foster graduates prepared to practice in the 21st-century health care system. Adequate preparation requires an explicit focus on the systems sciences as a vital and equal component of physician education.

'Articles (Medical Education) > 교육과정 개발&평가' 카테고리의 다른 글

| 보건시스템과학: 기본의학교육의 "브로콜리" (Acad Med, 2019) (0) | 2021.05.28 |

|---|---|

| 의학교육의 보건시스템과학: 변혁을 촉진하기 위한 요소의 통합(Acad Med, 2020) (0) | 2021.05.28 |

| 기본의학교육에서 보건시스템과학(HSS) 교육과정: 잠재적 교육과정 프레임워크 탐색 및 정의 (Acad Med, 2017) (0) | 2021.05.27 |

| 미래의 보건건문직교육: 미국의 트렌드(FASEB Bioadv, 2020) (0) | 2021.05.15 |

| 하버드 Pathways 교육과정: 현대 학습자를 위한 발달적으로 적합한 의학교육(Acad Med, 2020) (0) | 2021.04.30 |