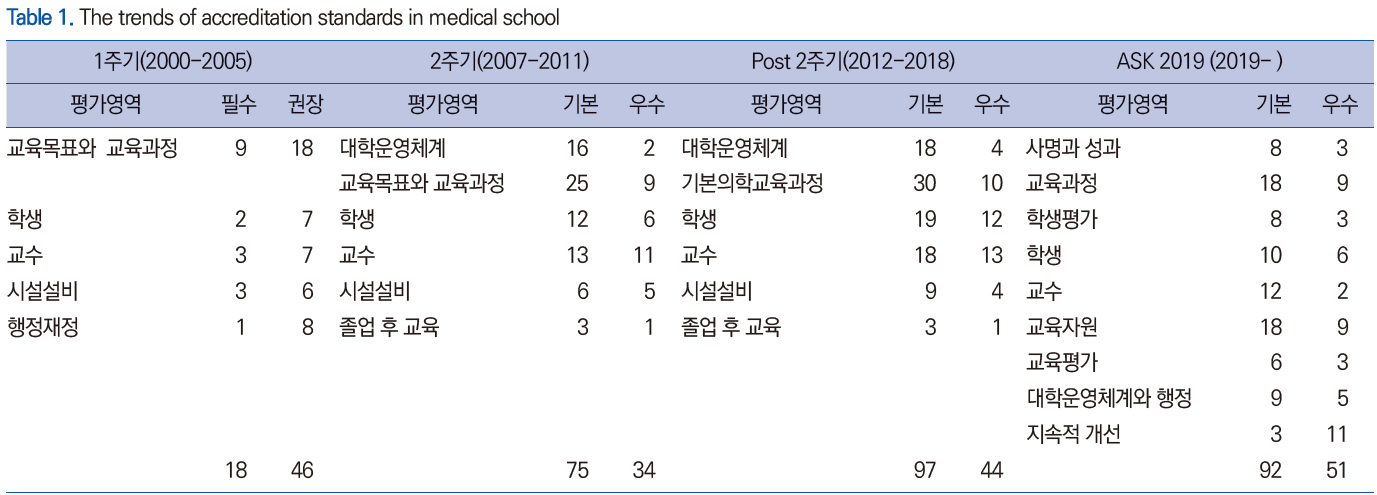

OSCE에서 합격선 설정: 경계선 접근법(Clin Teach. 2014)

Standard setting in OSCEs: a borderline approach

Kingston Rajiah , Sajesh Kalkandi Veettil and Suresh Kumar , Department of Pharmacy Practice , International Medical University , Kuala Lumpur , Malaysia

소개

Introduction

임상 술기 및 역량 평가는 응시자에게 중대한 결과를 초래하는 중요한 과정입니다.1 따라서 타당하고 신뢰할 수 있는 객관적 구조화 임상시험(OSCE)을 유지하기 위해서는 합격 점수를 정당화할 수 있는 강력한 방법이 필수적입니다.2 그러나 합격 점수가 부적절하게 설정되면 이러한 성취는 거의 의미가 없습니다.3

The evaluation of clinical skills and competencies is a high-stakes process carrying significant consequences for the candidate.1 Hence, it is mandatory to have a robust method to justify the pass score in order to maintain a valid and reliable objective structured clinical examination (OSCE).2 These attainments are of little significance if the passing score is set inadequately, however.3

임상 시험에서 표준을 설정하는 방법은 여전히 어려운 과제입니다.1 표준 설정에는 여러 가지 방법이 있으며, 각 방법에는 장점과 단점이 있으며, 각 방법마다 합격 점수가 다릅니다.4 표준 설정 방법은 시험 항목 또는 응시자의 성과에 따라 설정되는 상대적 또는 절대적 방법(경계선 방법)이 있습니다.5 표준 설정의 두 가지 광범위한 접근 방식 중 임상 역량 테스트에는 절대적 방법이 선호되었습니다.6, 7

The methods for setting standards in clinical examinations remain challenging.1 There are different methods for standard setting, each with benefits as well as drawbacks; each method gives a dissimilar pass mark.4 Standard-setting methods can be relative or absolute, established on either the test item or on the performance of the candidate (borderline methods).5 Of the two broad approaches in standard setting, the absolute method has been preferred for testing clinical competencies.6, 7

표준 설정에는 여러 가지 방법이 있으며, 각 방법에는 장점과 단점이 있습니다.

There are different methods for standard setting, each with benefits as well as drawbacks

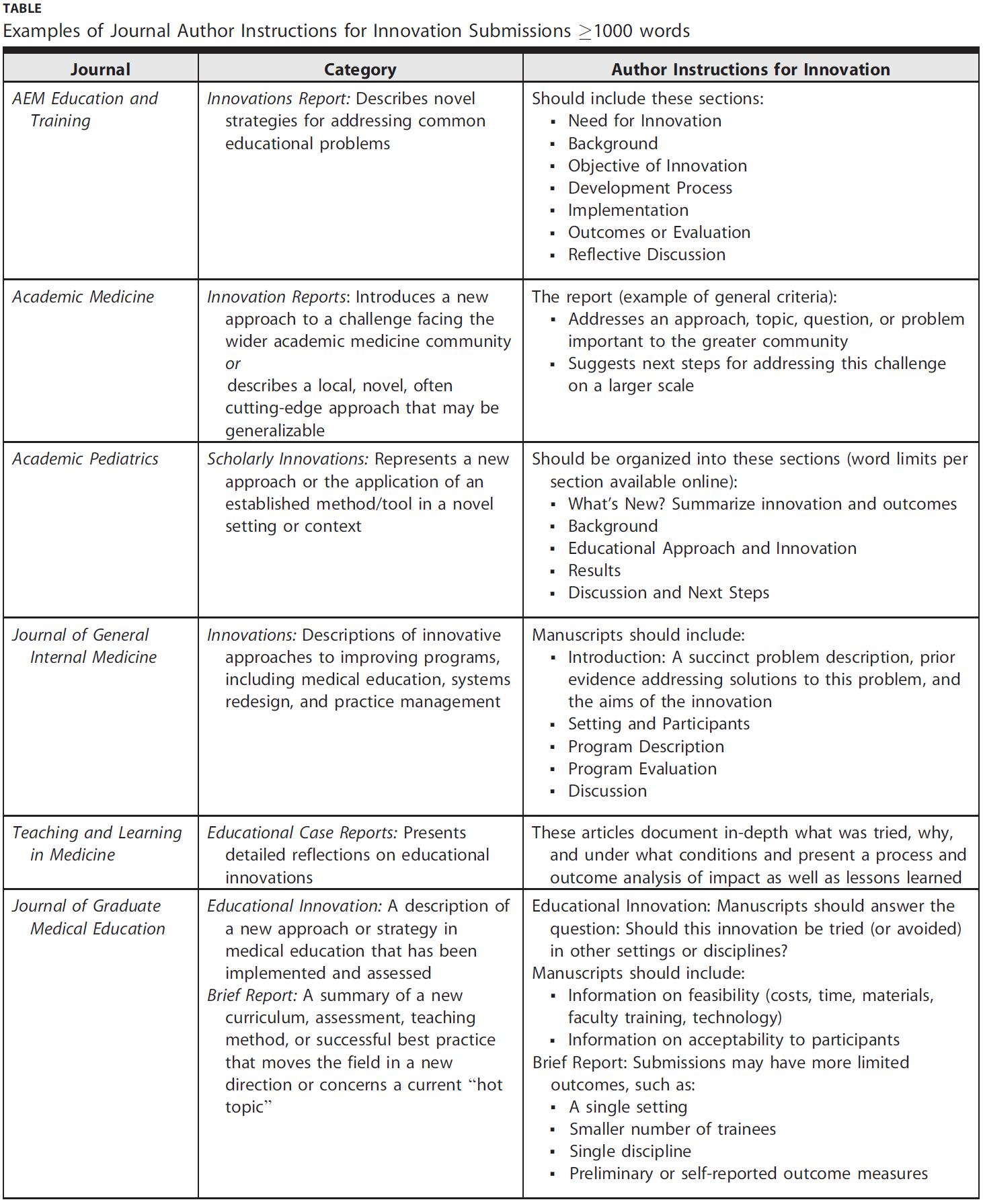

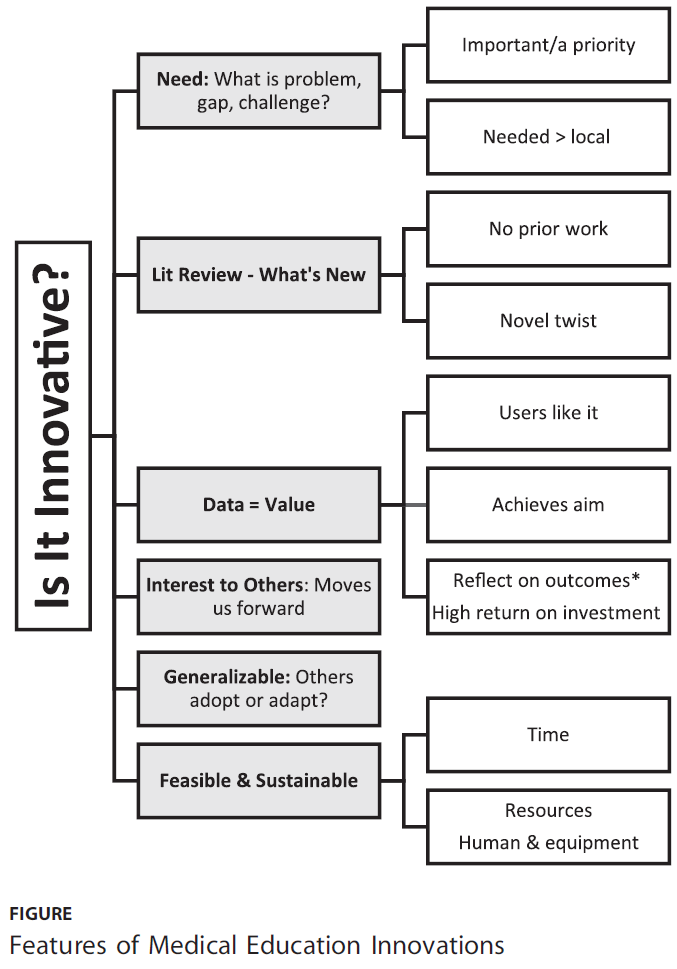

현재 많은 기관에서 경계선 및 회귀 접근법을 선호하는데, 이는 글로벌 등급과 체크리스트 점수 간의 관계 및 학생 간의 변별 수준을 관찰할 수 있는 이점을 제공합니다.5 이 접근법은 시험관이 각 스테이션에서 경계선에 있는 학생을 식별하는 데 도움이 되며 경계선 점수의 평균을 반영하여 각 스테이션의 합격 점수로 설정할 수 있습니다.4, 8 OSCE의 합격 점수는 각 스테이션의 합격 점수에 1 표준 오차를 더한 값입니다.8 이 방법은 다른 기존 방식과 비교할 때 평가자의 시간을 절약할 수 있는 방법입니다. 따라서 OSCE의 표준 설정을 위해 두 가지 영역의 글로벌 평가 척도를 사용하여 경계선 접근법을 시험해 보는 것이 목표였습니다.

Presently, many institutions favour borderline and regression approaches, which can offer the advantage of observing the relationship between global rating and checklist scores, and also the level of discrimination between the students.5 This approach helps examiners to identify the borderline students at each station and also reflects the mean of the borderline marks, which can be set as the pass mark for each station.4, 8 The pass mark for the OSCE is the sum of the pass marks for each station plus one standard error of measurement.8 Compared with the other established approaches, this method is a time saver for the assessors. Hence, the aim was to trial the borderline approach using a two-domain global rating scale for standard setting in the OSCE.

우리의 일반적인 목표는 작업 기반 체크리스트 점수와 글로벌 등급 간의 상관관계를 분석하는 것이었습니다.

Our general objective was to analyse the correlation between the task-based checklist score and the global rating.

구체적인 목표는 경계선 방식에 따라 각 OSCE 스테이션에서 최소 합격 점수를 결정하는 것이었습니다.

Our specific objective was to determine the minimum pass mark in each OSCE station according to the borderline method.

연구 방법

Methods

이 연구는 약학 학부 2학년 학생들을 대상으로 횡단면 연구를 수행했습니다. 2013년 학기 말에 실시된 OSCE가 본 연구의 연구 대상이었습니다. Raosoft 표본 크기 계산기를 사용하여 표본 크기 계산을 수행했습니다. 필요한 최소 표본 크기는 116명이었으며 오차 범위는 5%, 신뢰 수준은 95%였습니다. 표본을 수집하기 위해 편의 표본 추출 기법을 사용했습니다. 약대생 164명의 결과가 분석에 사용되었는데, 이는 계산된 필수 표본 크기보다 많았습니다.

This was a cross-sectional study carried out with second-year undergraduate pharmacy students. The OSCE conducted at the end of the semester in 2013 was the research subject of this study. A sample size calculation was performed using the Raosoft sample size calculator. The minimum required sample size was 116 with a 5 per cent margin of error and 95 per cent confidence level. A convenience sampling technique was used to collect the sample. The results for 164 pharmacy students were used in the analysis, which was more than the required calculated sample size.

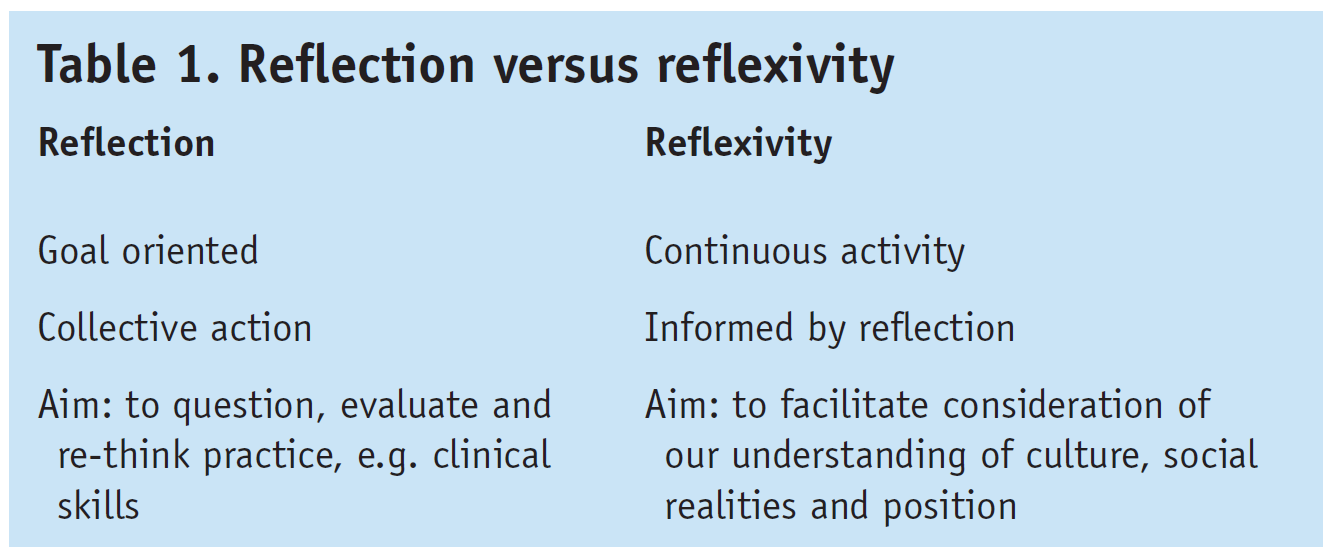

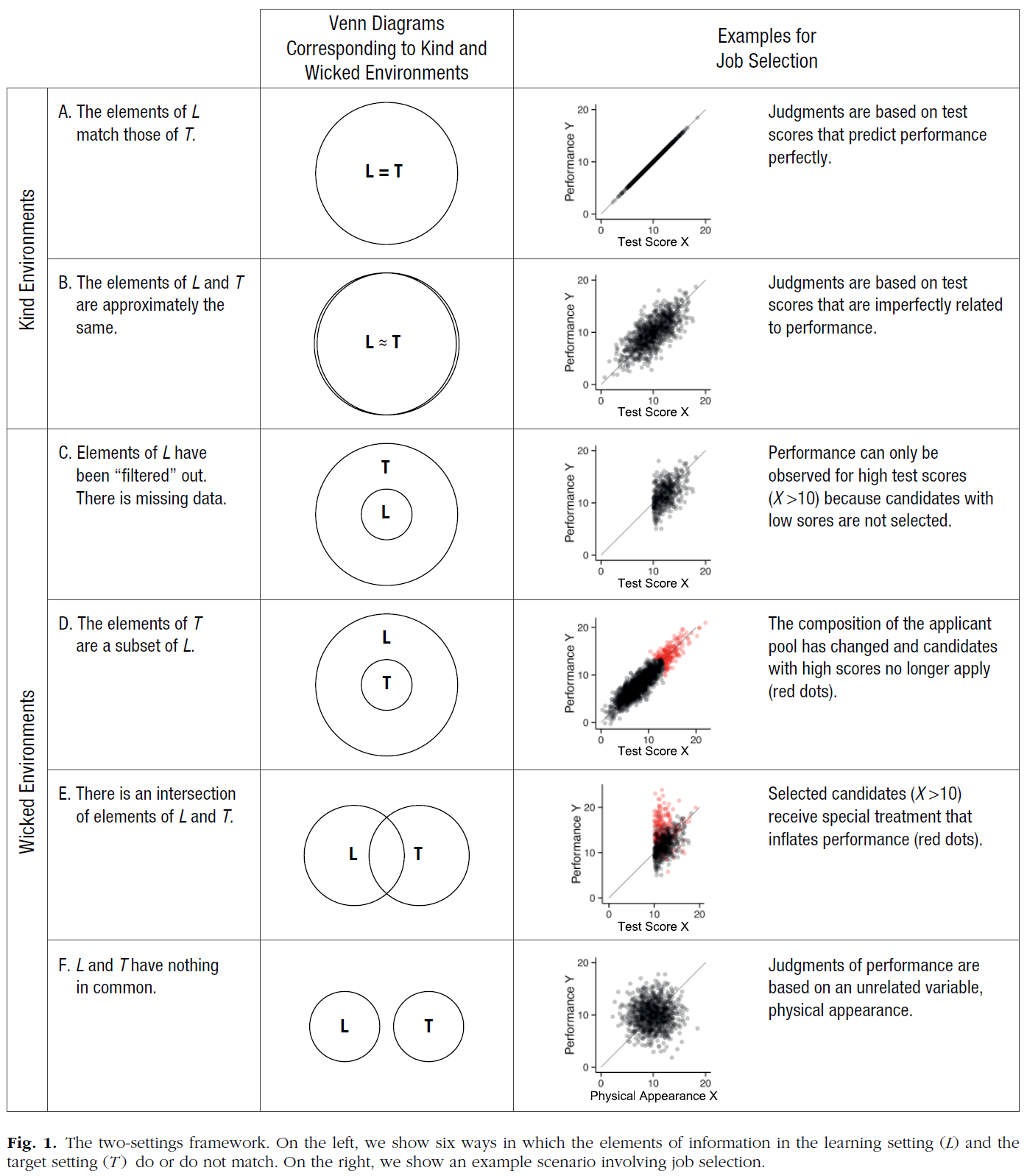

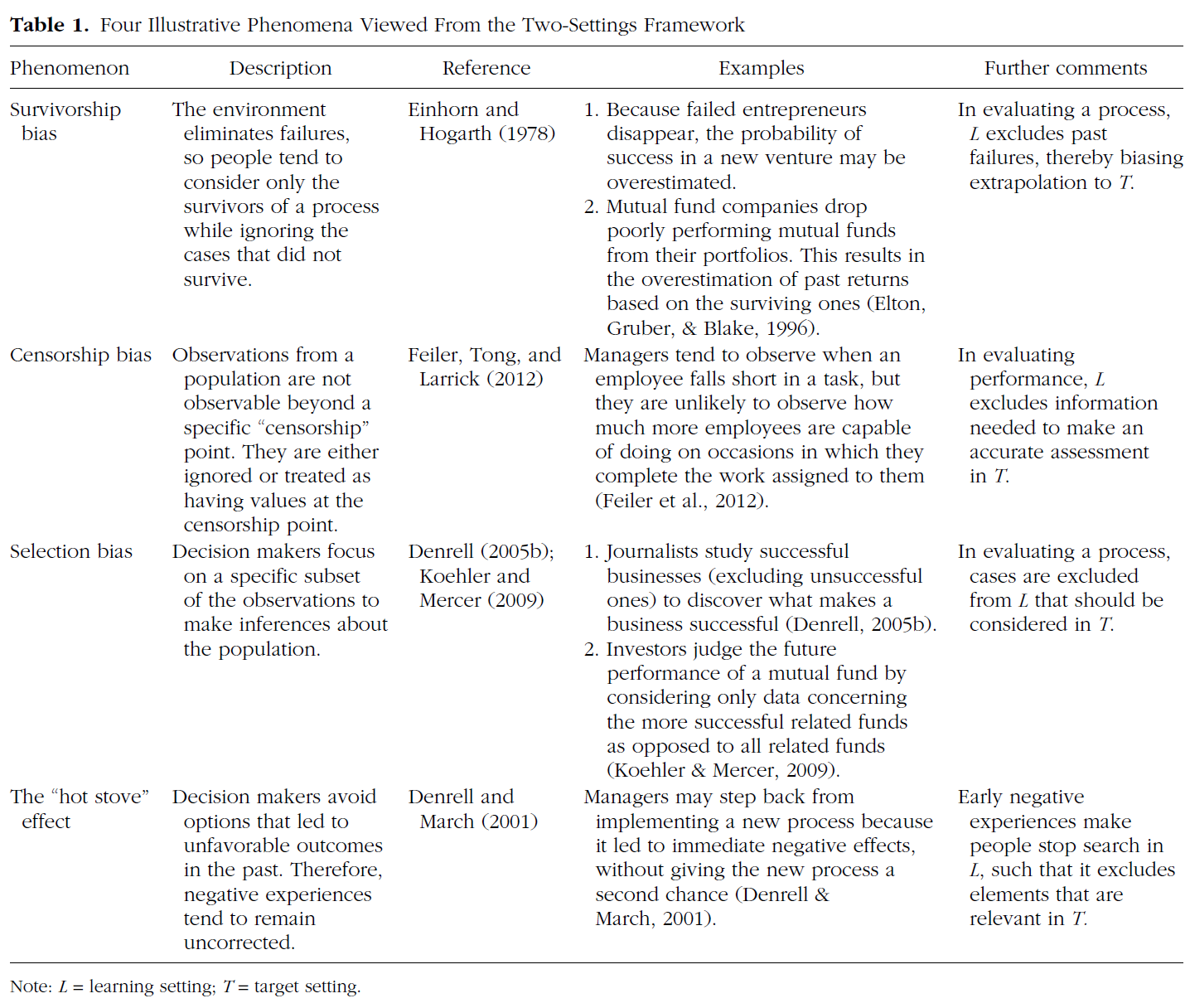

2학년 OSCE는 총 14개의 스테이션이 직렬로 연결된 회로로 구성되었습니다. 각 스테이션에 할당된 시간은 5분이었습니다. 스테이션은 활동, 준비, 휴식으로 분류되었습니다(표 1). 학생들은 스테이션의 회로를 돌며 각 활성 스테이션에서 과제를 수행했습니다.9 학생들이 활성 스테이션에 들어가기 전에 과제를 준비할 수 있도록 준비 스테이션이 포함되었습니다. 시험이 진행되는 15분마다 학생들을 위한 휴식 스테이션이 포함되었습니다. 시험관은 표준화된 과제 기반 체크리스트를 사용하여 각 활성 스테이션에서 표준화된 모의 환자에 대한 학생의 수행을 관찰하고 평가한 후 두 가지 영역의 글로벌 등급 척도를 사용하여 평가했습니다.

The second-year OSCE had a circuit of 14 stations in total, which were connected in a series. The time allotted for each station was 5 minutes. The stations were categorised as active, preparatory and rest (Table 1). Students rotate around the circuit of stations, and perform the tasks at each active station.9 A preparatory station was included for the students to prepare for the task before entering into the active station. A rest station for the students was incorporated after every 15 minutes in the exam. The student's performance with a standardised simulated patient in each active station was observed and evaluated by an examiner using a standardised task-based checklist, followed by a two-domain global rating scale.

OSCE에 사용된 모든 시나리오는 새로운 스크립트였기 때문에 학생들이 이전에 접해본 적이 없었습니다. 체크리스트와 글로벌 평가 척도는 모두 시험관들 사이에서 검증되고 표준화된 후 OSCE에서 사용되었습니다. 다양한 분야의 표준화된 임상 교수진이 시험관으로 참여했습니다.

All the scenarios used in the OSCE were new scripts, and therefore had not been encountered by the students previously. Both checklists and the global rating scales were validated and standardised among examiners before using them in the OSCE. Standardised clinical faculty members from a variety of disciplines served as examiners.

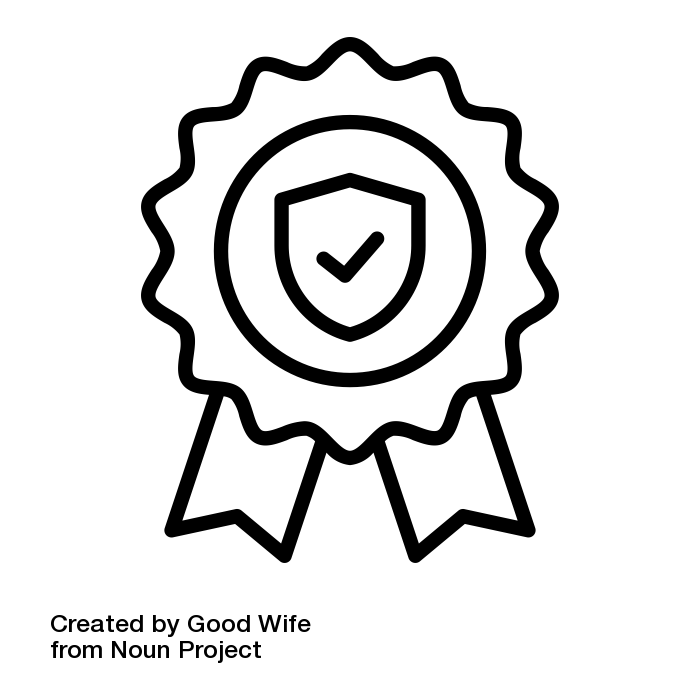

각 스테이션의 임상 시나리오와 과제 기반 체크리스트는 약학 실습 교수진이 모듈의 학습 결과와 학생의 학습 수준에 따라 구성했습니다. 시험 콘텐츠는 기본적인 '블루프린팅'를 통해 학습 목표에 맞게 계획되었습니다. 모듈 결과와 과제 기반 체크리스트를 기반으로 핵심 역량을 파악하여 체크리스트의 전반적인 기준을 나타내는 두 가지 영역의 글로벌 평가 척도로 개발했습니다. 각 영역에 대해 6점 척도 세트를 사용하여 높고 낮은 부분을 반영했습니다(5점, 우수 합격, 4점, 만족 합격, 3점, 합격' 2점, 경계 합격, 1점, 불합격, 0점, 명백한 불합격). 두 개별 영역의 점수를 합산하여 '합산된 글로벌 등급'을 만들었습니다. 개별 스테이션에 대한 작업 기반 체크리스트 점수는 14점 만점으로 채점되었습니다. 활성 스테이션이 5개였으므로 작업 기반 체크리스트의 총 점수는 70점이었습니다. 따라서 35점(70점의 50% 임의로)을 합격 점수로 유지했습니다(상자 1). SPSS 18을 사용하여 과제 기반 체크리스트 점수와 두 영역의 글로벌 평가 척도 간의 상관관계를 Pearson의 상관관계 테스트를 통해 분석했습니다. 유의 수준은 p <0.05로 설정했습니다. 각 스테이션의 체크리스트 점수와 글로벌 등급 간의 (선형) 상관관계를 결정하기 위해 R2 계수를 사용했으며, 일반적으로 전체 글로벌 등급이 높을수록 체크리스트 점수도 높을 것으로 예상했습니다. 이 R2 값으로부터 OSCE의 최소 합격 점수가 결정되었습니다. 경계선 등급은 시험관이 스테이션을 통과하기에는 성적이 부족하다고 생각하지만 명백하게 불합격하지는 않은 학생을 나타냅니다. 그런 다음 학생들의 체크리스트 점수와 글로벌 등급이 집계되었습니다. 그런 다음 시험관이 부여한 해당 글로벌 성적에 대해 스테이션 체크리스트 점수 집합을 회귀시켜 스테이션의 각 개별 합격 점수를 계산했습니다. 이 과정을 통해 합격 또는 불합격 점수가 도출되었습니다. 연구의 전체 절차는 그림 1에 흐름도로 나와 있습니다.

Clinical scenarios and task-based checklists for each station were formulated by pharmacy practice faculty members, based on the learning outcomes of the module and the students’ level of learning. The test content was planned against the learning objectives through basic ‘blueprinting’. Based on the module outcomes and the task-based checklists, key competencies were identified and developed into a two-domain global rating scale, which generally represented the overall criteria in the checklists. For each domain a set of six-point scales were used to reflect high and low divisions (5, excellent pass; 4, satisfactory pass; 3, pass’ 2, borderline pass; 1, fail; 0, clear fail). Scores on the two individual domains were summed to create a ‘summed global rating’. Task-based checklist scores for individual stations were scored out of 14 marks. There were five active stations, and hence the total score of the task-based checklists was 70 marks. Therefore, a pass mark of 35 (arbitrarily 50% of 70) was kept as pass mark (Box 1). spss 18 was used to analyse the correlation between the task-based checklist scoring and the two-domain global rating scale by Pearson's correlation test. The level of significance was set at p < 0.05. The R2 coefficient was used to determine the degree of (linear) correlation between the checklist score and the global rating at each station, with the expectation that higher overall global ratings should generally correspond with higher checklist scores. From these R2 values the minimum pass mark for the OSCE was determined. The borderline grade represented students whose performances the examiner thought insufficient to pass the station, but equally who did not clearly fail. Following this, the students’ checklist scores and global ratings were gathered. Each individual pass mark for the station was then calculated by regressing the set of station checklist scores on the corresponding global grades given by the examiners. This process then derived the pass or fail score. The entire procedure of the study is given as a flow chart in Figure 1.

다양한 분야의 교수진이 시험관으로 참여했습니다.

Faculty members from a variety of disciplines served as examiners

시험 결과

Results

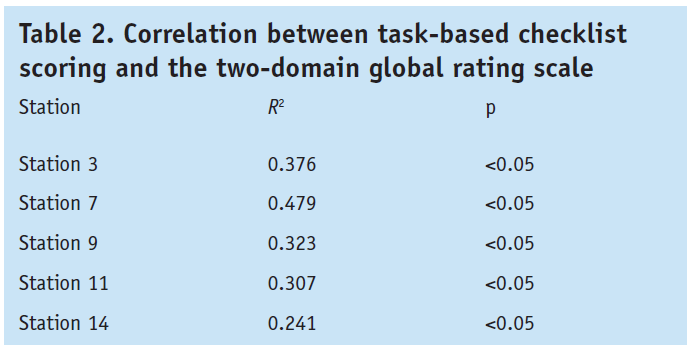

총 164명의 응시자가 참여했으며, 이 중 126명이 여성, 38명이 남성이었습니다. 전체 글로벌 평가 점수의 신뢰도 계수(크론바흐 알파)는 모든 현역 스테이션에서 0.722~0.741로 체크리스트 점수(현역 스테이션의 항목별 0.601~0.686)보다 높은 값을 보였습니다. 과제 기반 체크리스트 점수와 두 가지 영역의 글로벌 평가 척도 간의 피어슨 상관관계는 중간 정도이며 유의미했습니다. 스테이션 7의 R2 계수가 0.479로 가장 높았고 스테이션 14의 계수가 0.241로 가장 낮았습니다(표 2). 총 14개 중 각각 5개의 활성 스테이션이 있었으므로 모든 활성 스테이션의 총 체크리스트 점수는 70점, 평균 점수는 52.5점이었습니다(표 3). 마찬가지로 전체 글로벌 등급의 평균 점수는 50점 만점에 29.7점이었습니다.

There were 164 participating candidates, of which 126 were women and 38 were men. The reliability coefficient (Cronbach's alpha) for overall global rating scores showed a value ranging from 0.722 to 0.741 across all active stations, which was higher than the checklist scoring (0.601–0.686 across items for active stations). The Pearson's correlation between the task-based checklist scoring and the two-domain global rating scale were moderate and significant. A highest R2 coefficient of 0.479 was obtained for station 7, and the lowest value of 0.241 was obtained for station 14 (Table 2). There were total of five active stations, each marked out of 14, so the total possible checklist score for all active stations was 70, with the mean score of 52.5 (Table 3). Similarly, the mean score for the total global grade was 29.7 out of 50.

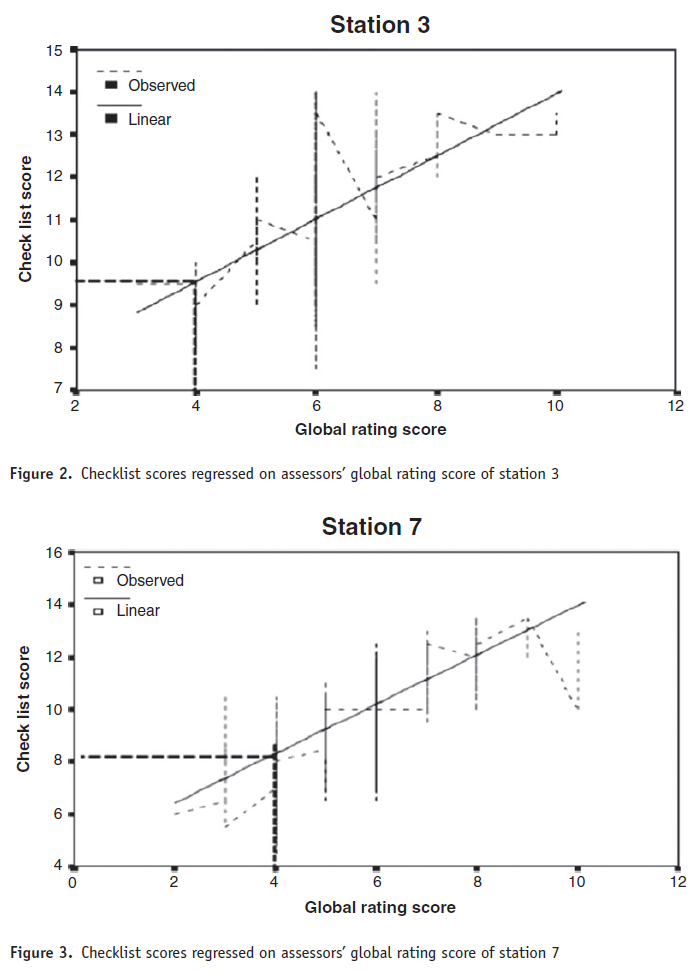

그림 2-6은 시험장 합격 점수에 대한 경계선 방법 계산을 개략적으로 보여 주며, 시험관의 체크리스트 점수를 시험관의 글로벌 등급 점수에 회귀시키는 선형 회귀 기법을 사용하여 각 활성 시험장의 합격 점수를 계산한 방법을 나타냅니다. 합격 점수는 경계선 평균에 1 표준 오차(0.67)를 더한 값의 합계였습니다: 44.9점 또는 64퍼센트.

Figures 2-6 present the borderline method calculation for the station pass mark in schematic terms, indicating how the linear regression technique of the examiners’ checklist scores regressed on the examiners’ global rating scores was used to calculate the pass mark at each active station. The pass mark was the sum of the borderline means plus one standard error of measurement (0.67): 44.9 or 64 per cent.

두 척도 사이에는 유의미한 양의 상관관계가 있었습니다.

There was a significant positive correlation between the two scales

토론

Discussion

두 척도 간에는 유의미한 양의 상관관계가 있었지만, 7번 문항을 제외하고는 R2 값이 만족스럽지 않았습니다. 경계선 방식에 따른 OSCE의 합격 점수는 64%로 임의로 설정한 점수인 50%보다 높았습니다.

There was a significant positive correlation between the two scales; however, the R2 value was not satisfactory, except for station 7. The pass mark for the OSCE according to the borderline method was 64 per cent, which is higher than the arbitrarily set mark of 50 per cent.

각 활성 스테이션의 합격 점수 차이는 작았지만, 14번 스테이션은 약물 상담 스테이션으로 합격 점수가 6.99/14에 불과하여 다른 활성 스테이션보다 낮았습니다(그림 2-6). 이는 종속 변수(체크리스트 점수)와 독립 변수(글로벌 등급) 사이에 반비례 관계가 있음을 분명히 나타냅니다.5

The variation in pass marks for each active station was small, except for station 14: it was a drug-counselling station, and the pass mark was only 6.99/14, which is lower than the other active stations (Figures 2-6). This clearly indicates an inverse proportionality between the dependent variable (checklist score) and the independent variable (global rating).5

일부 학생은 두 영역의 글로벌 등급에서 더 높은 점수를 받았지만 체크리스트 점수는 기대 수준에 미치지 못했습니다. 경계선 응시자의 점수가 이렇게 큰 차이를 보인다는 것은 시험관마다 체크리스트 또는 글로벌 등급 기준을 다르게 해석하고 있음을 시사하며, 시험관 표준화가 필요하다는 것을 나타냅니다. 체크리스트 점수와 글로벌 등급 사이의 불만족스러운 연관성은 대부분의 스테이션에서 볼 수 있으며, 이로 인해 어느 정도의 비선형성이 발생했습니다. 일부 스테이션에서는 경계선 이하로 평가된 학생 수가 더 많았으며, 이는 이러한 스테이션에 대한 평가가 필요하다는 것을 나타냅니다.

Some students acquired higher marks from the two-domain global grade, but their checklist marks did not attain the expected level. This wide variation in marks for borderline candidates suggests that different examiners are interpreting the checklists or the global rating criteria differently, and indicates the need for examiner standardisation, which is challenging. This unsatisfactory association between checklist marks and global ratings can be seen in most of the stations, which has caused some degree of nonlinearity. Some stations had a greater number of students who were rated as borderline or below, which indicates that there is a need for an appraisal of these stations.

일부 스테이션의 R2 값이 낮았지만, 글로벌 평가 척도는 체크리스트의 전반적인 기준을 정확하게 나타내도록 설계되었습니다. 따라서 불만족스러운 상관관계는 심사자 간에 글로벌 등급 척도와 체크리스트의 표준화가 제대로 이루어지지 않았거나 글로벌 등급 시스템 사용법에 대한 이해가 부족하기 때문에 발생할 수 있습니다. 이 분석 과정을 통해 표준 설정에 대한 경계선 접근 방식이 실현 가능하고 평가 중에 사용할 수 있으며 다른 방법보다 훨씬 적은 시간이 필요하다는 것이 입증되었습니다. 그러나 여기서 확인된 문제점을 해결해야 하며, 스테이션 체크리스트의 표시 체계와 글로벌 등급 기준을 재평가해야 합니다. 향후 OSCE에서 표준 설정 절차를 구현하기 전에 이러한 문제를 해결하는 것이 중요합니다.

Although the R2 value at some stations was low, the global rating scale was designed to represent the overall criteria of the checklists exactly. Hence, the unsatisfactory correlation may arise from the improper standardisation of the global scale and the checklist among examiners, or from a poor understanding of how to use the global rating system. The process of this analysis demonstrated that the borderline approach to standard setting is feasible and can be used during the assessment, thereby requiring much less time than the other methods. But the problems identified here must be addressed, and the marking schemes for the station checklists and criteria for the global rating should be reassessed. It is important to resolve these problems before implementing the standard setting procedure in future OSCEs.

여기서 확인된 문제점을 해결해야 합니다.

Problems identified here must be addressed

결론

Conclusions

글로벌 등급 척도를 사용하면 많은 이점이 있습니다. 글로벌 등급 척도는 체크리스트보다 다양한 수준의 숙련도를 더 잘 파악할 수 있고 시험관이 사용하기 쉽다는 증거가 있습니다. 이 연구는 두 영역의 글로벌 평가 척도가 OSCE의 틀에서 학생들의 능력을 평가하는 데 적합하다는 것을 확인시켜 줍니다. 두 영역 글로벌 평가 척도와 과제 기반 체크리스트 간의 강력한 관계는 두 영역 글로벌 평가 척도가 학생의 숙련도를 진정으로 평가하는 데 사용될 수 있다는 증거를 제공합니다.

The use of a global rating scale has numerous benefits. There is evidence that global rating scales capture diverse levels of proficiencies better than checklists, and are easy for examiners to use. This study confirms that the two-domain global rating scale is appropriate to assess the abilities of students in the framework of OSCEs. The strong relationship between the two-domain global rating scale and the task-based checklists provide evidence that the two-domain global rating scale can be used to genuinely assess students’ proficiencies.

두 영역 글로벌 평가 척도는 OSCE의 틀에서 학생의 능력을 평가하는 데 적합합니다.

The two-domain global rating scale is appropriate to assess the abilities of students in the framework of OSCEs

Standard setting in OSCEs: a borderline approach

PMID: 25417986

DOI: 10.1111/tct.12213

Abstract

Background: The evaluation of clinical skills and competencies is a high-stakes process carrying significant consequences for the candidate. Hence, it is mandatory to have a robust method to justify the pass score in order to maintain a valid and reliable objective structured clinical examination (OSCE). The aim was to trial the borderline approach using the two-domain global rating scale for standard setting in the OSCE.

Methods: For each domain, a set of six-point (from 5 to 0) scales were used to reflect high and low divisions within the 'pass', 'borderline' and 'fail' categories. Scores on the two individual global scales were summed to create a 'summed global rating'. Similarly task-based checklists for individual stations were summed to get a total score. It is mandatory to have a robust method to justify the pass score in order to maintain a valid and reliable OSCE RESULTS: The Pearson's correlation between task-based checklist scoring and the two-domain global rating scale were moderate and significant. The highest R(2) coefficient of 0.479 was obtained for station 7, and the lowest R(2) value was 0.241 for station 14.

Discussion: There was a significant positive correlation between the two scales; however, the R(2) value was not satisfactory except for station 7. The pass mark for the OSCE according to the borderline method was 64 per cent, which is higher than the arbitrarily set pass mark of 50 per cent.

Conclusions: This study confirms that the two-domain global rating scale is appropriate to assess the abilities of students within the framework of an OSCE. The strong relationships between the two-domain global rating scale and task-based checklists provide evidence that the two-domain global rating scale can be used to genuinely assess students' proficiencies.

© 2014 John Wiley & Sons Ltd.