의료시스템과학 등장의 역사적 배경: 1910년대부터 2010년대까지의 미국 의료 체계 개혁과 의학교육을 중심으로(Korean J Med Hist, 2023)

공혜정*

1. 서론

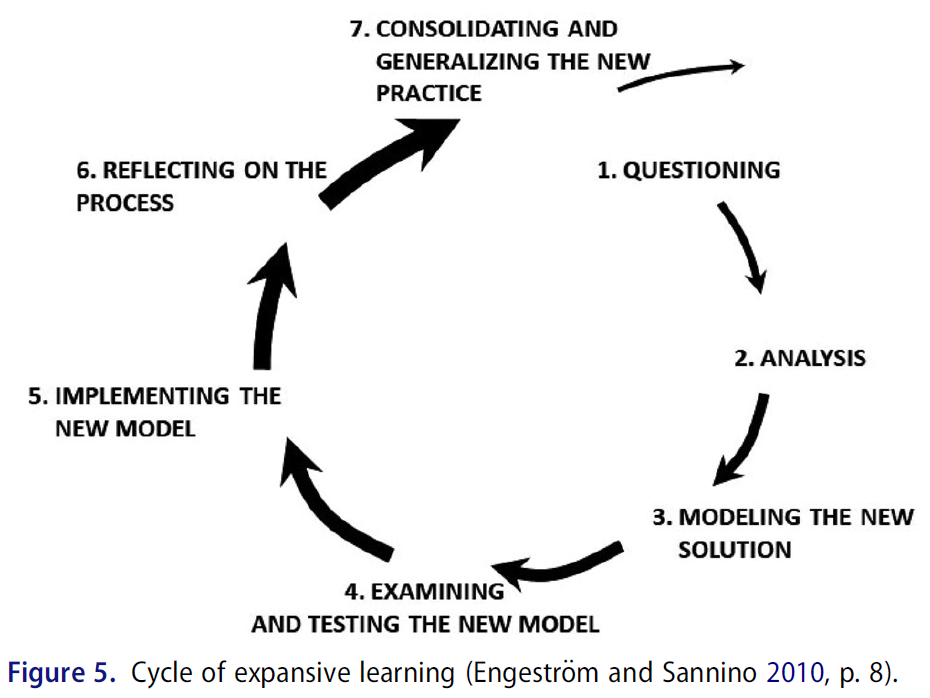

의료시스템과학(Health Systems Science, HSS)은 미국 의학교육에서 기초 의학(Basic medical science)과 임상의학(Clinical medical science) 외의 나머지 부문을 “제3의 영역(third pillar)”이라는 이름 아래 도입한 분야이다. 이는 구체적으로 다양한 인구 집단과 환자들의 보건의료에 대한 요구를 충족하기 위해 관련 서비스를 제공하는 사람, 기관 및 자원의 조직 등에 관하여 연구하거나 교육하는 것이다. 포괄적으로 HSS는 일차적으로 ‘질병에 대처하는 모든 인간 행위와 관련 영역을 포괄하여 총칭’하고 있다(Skochelak et al., 2021: 11; 이종태 외, 2021: 3). 미국의사협회(American Medical Association, AMA)는 HSS를 의학교육에 도입하기 위해 2013년 미국의 141개 의과대학 중 11개 의과대학을 선발하여 각 대학에 연간 100만 달러씩 지원하여 HSS 교육과정을 시범적으로 실시하였다. 이후 HSS 시범 교육 사업 대상은 2016년에는 32개, 2019년에는 37개 학교로 늘어났다. 이는 전체 일반의과(Allopathic medicine)대학과 정골의학(Osteopathic medicine)대학의 약 1/5에 해당한다(Skochelak et al., 2021: Preface). AMA는 2013년에서 2018년까지 총 1,250만 달러를 투자하였다(이종태 외. 2021: 15-16). AMA는 2013년 “의학교육의 변화 가속화(Accelerating Change in Medical Education)” 추진안을 제시하고, 컨소시엄을 구성하였다. 이 컨소시엄에서는 HSS를 통해서 기초의학 교육과 임상의학 교육을 보완하는 것이 일차 목표이다. 궁극적으로 HSS를 통하여 의료의 질 향상, 의료의 가치 증대, 환자 안전 향상, 인구 기반 의료 제공, 협력적 팀 활동, 사회 생태학적 인식, 건강 결정 요인과 건강관리 정책 및 경제에 대한 이해 등을 달성하는 포괄적인 개혁을 꾀하고 있다(Gonzalo et al, 2017: 124).

현재 미국 의학교육 분야에서 HSS 도입 및 적용에 관한 연구는 증가하고 있다. 과연 무엇이 의학교육에 HSS를 도입시켰는가?

- 조지 E. 티볼트(George E. Thibault)는 HSS와 비슷한 경향-즉 전문직종간(interprofessional) 협력, 만성 질환에 관한 관심과 종단적인 통합 의학교육, 사회결정요인에 관한 관심, 평생 학습, 역량 기반(competency-based) 보건행정 교육, 새로운 정보 기술의 도입 등-이 부상하고 있음을 지적하였다(Thibault, 2020).

- 제프리 M. 볼칸(Jeffrey M. Borkan)과 몇몇 학자들은 HSS의 등장 배경은 플렉스너 리포트1) 이후 변화된 의료 현장의 모습에 대처하기 위한 것이라고 지적하였다. 즉 만성 질환의 급증, 한 명의 의사가 아닌 팀워크가 강조되는 의료현장, 병원보다는 지역사회 의료의 중요성, 인구 집단 보건 문제의 대두 등이 HSS가 등장하게 된 원인으로 꼽고 있다(Borkan, et al., 2021).

- 제드 D. 곤잘로(Jed D. Gonzalo)와 일부 학자들은 HSS의 주요 개념들은 갑자기 출현한 것이 아니라 일찍이는 1960년부터 시작해서 1990년대 말에 출현한 것으로 지적하고 있다(Gonzalo, et al., 2020).

===

1) 이것은 1910년 카네기재단(Carnegie Foundation)의 후원으로 에이브러햄 플렉스너(Abraham Flexner)가 작성한 미국과 캐나다의 의학 교육에 대한 보고서이다. 이 보고서에서는 미국 의과대학이 더 높은 입학 및 졸업 기준을 제정하고, 임상 의학뿐만 아니라 기초 의학 역시 비중 있게 교육해야 한다고 지적하였다. 자세한 내용은 플렉스너 보고서를 참조하시오(Flexner, 2005).

===

이 학자들은 HSS의 대두를 모두 의학 교육의 경향나 흐름, 의료현장의 변화 속에서 고찰하고 있지만, 실제로 역사적으로 어떤 변화가 일어났는지는 구체적으로 논의하지 않는다. 이 연구에서는 기존의 논의를 바탕에 두고 HSS의 출현을

- 첫째는 2010년에 입안된 ‘오바마케어(ObamaCare)’로 알려진 「의료보험개혁법(Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act, PPACA)」의 등장까지의 의료 체계의 변화와,

- 둘째는 미국 의학 교육의 변화 속에서 그 답을 찾고자 한다.

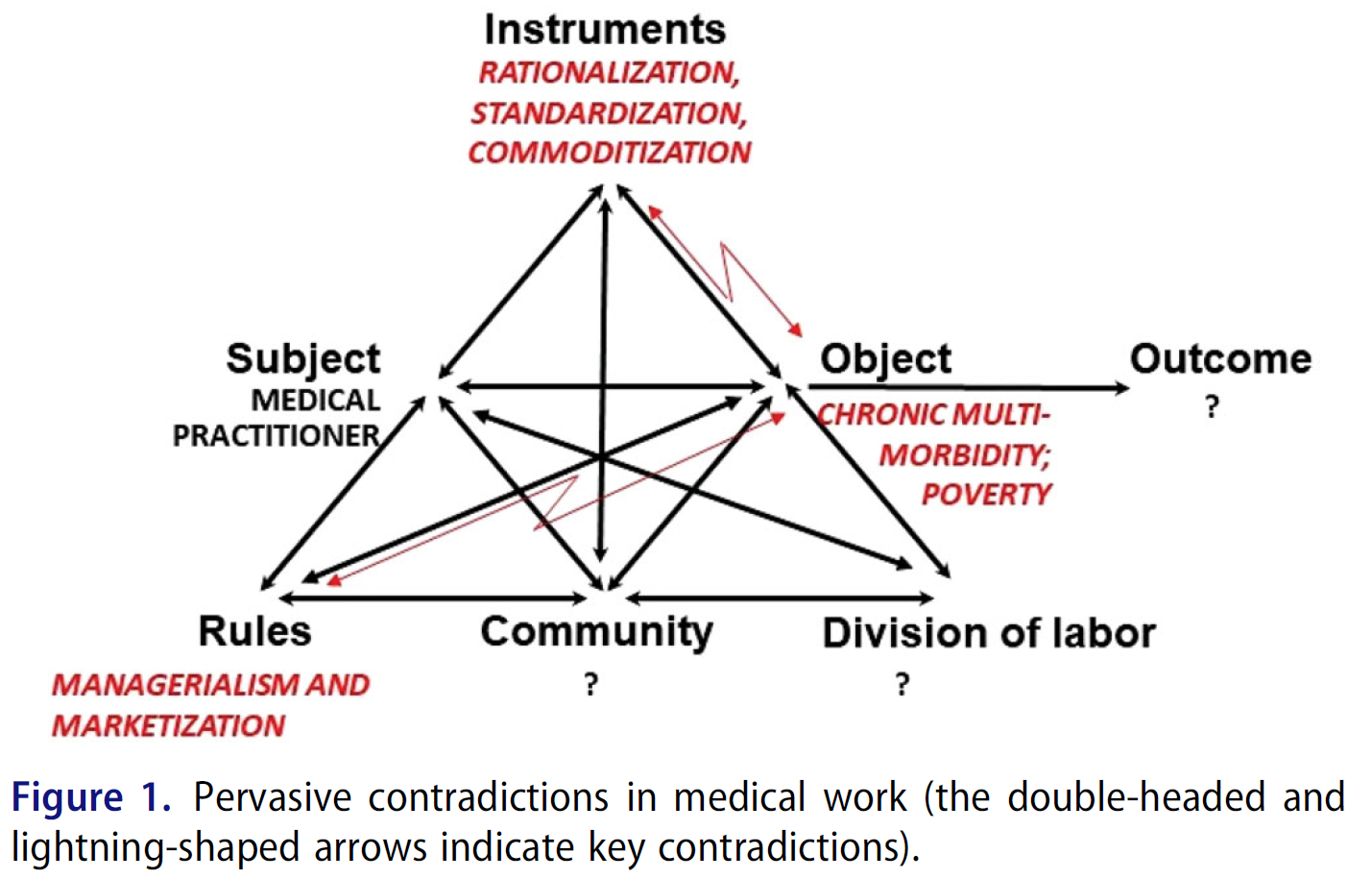

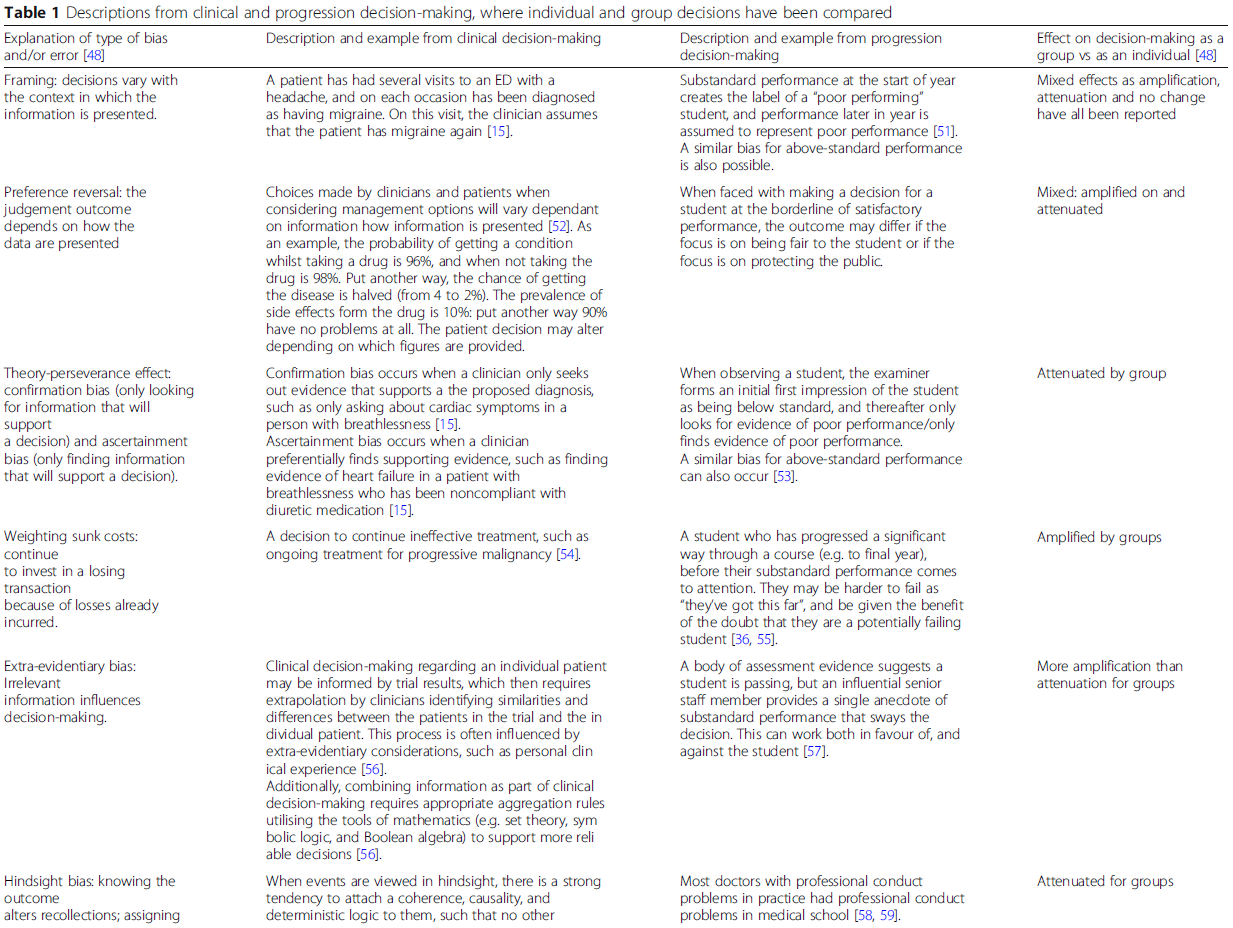

20세기와 21세기 미국의 의료체계는 ‘복잡성(complexity)’을 증대시키는 체계로 발전해 왔다. <그림 1>에서 보듯이 의료체계의 ‘복잡성’은 연방정부와 주 정부의 규제, 의사 · 간호사 · 약사 등에 대한 면허법, 보험회사 등에 의해 더 커졌다. 미국 의료 체계에는 약 3억 명이 넘는 이해관계자와 함께 1,400만 사람들이 고용되어 있다. 2009년에는 전체 국가 지출의 43.6%가 정부 의료 관련 프로그램에 관련된 지출이었고, 총 지출액 기준에서 볼 때 최고로 지출이 많은 산업으로 꼽혔다(Whitehead & Scherer 2013: 317). 또한, 미국의 의학교육 역시 여러 기관, 즉 ‘미국의사협회 의학교육위원회(The Council of Medical Education of The American Medical Association),’ ‘미국의과대학협회(The Association of American Medical Colleges, AAMC),’ ‘졸업 후 의학교육위원회(The Council on Graduate Medical Education, COGME),’ ‘졸업 후 의학교육인증위원회(The Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education, ACGME)’의 영향을 받는다. 이렇게 복잡한 의료체계와 교육체계 속에서 HSS는 의료비용을 낮추고 의료 혜택의 효율성을 극대화하기 위한 토대를 제공한다는 목적에서 출범하였다.

본 연구에서는 2장에서 HSS 개념과 미국 의과대학에서의 HSS 도입과 적용 현황에 대해서 살펴보고자 한다. 3장에서는 1910년에서 오바마케어까지의 의료개혁 노력에 대해서 살펴볼 것이다. 4장에서는 1910년에서 HSS 등장까지의 미국 의학교육계의 변화에 대해서 고찰할 것이다.

2. HSS 기본 구조 이해 및 교육 현황

1) HSS 기본 구조

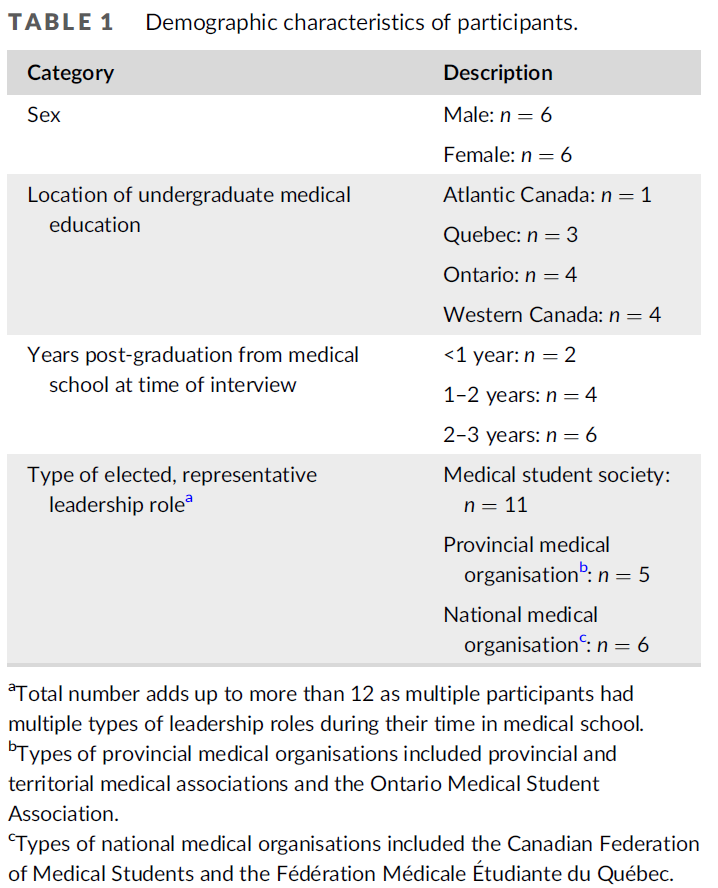

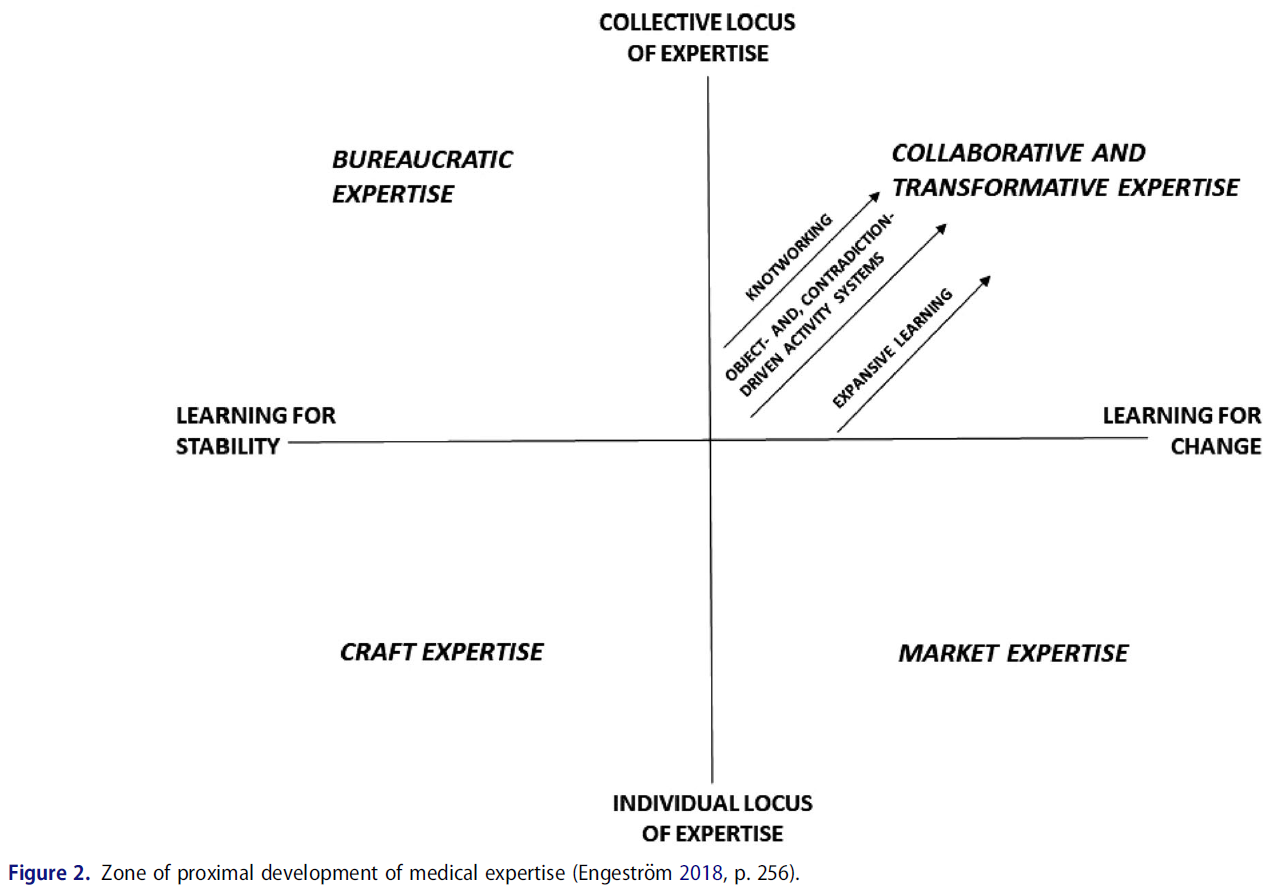

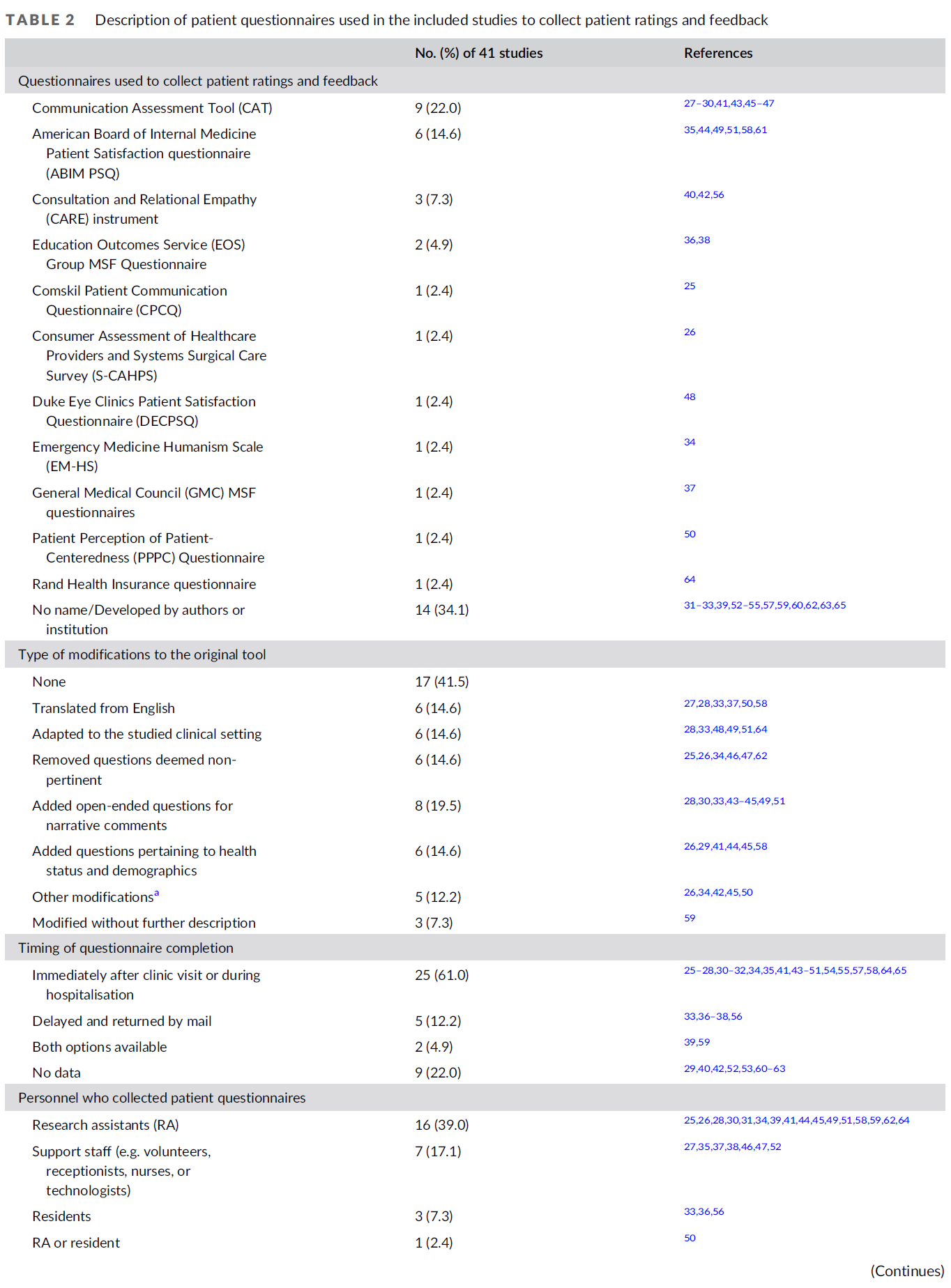

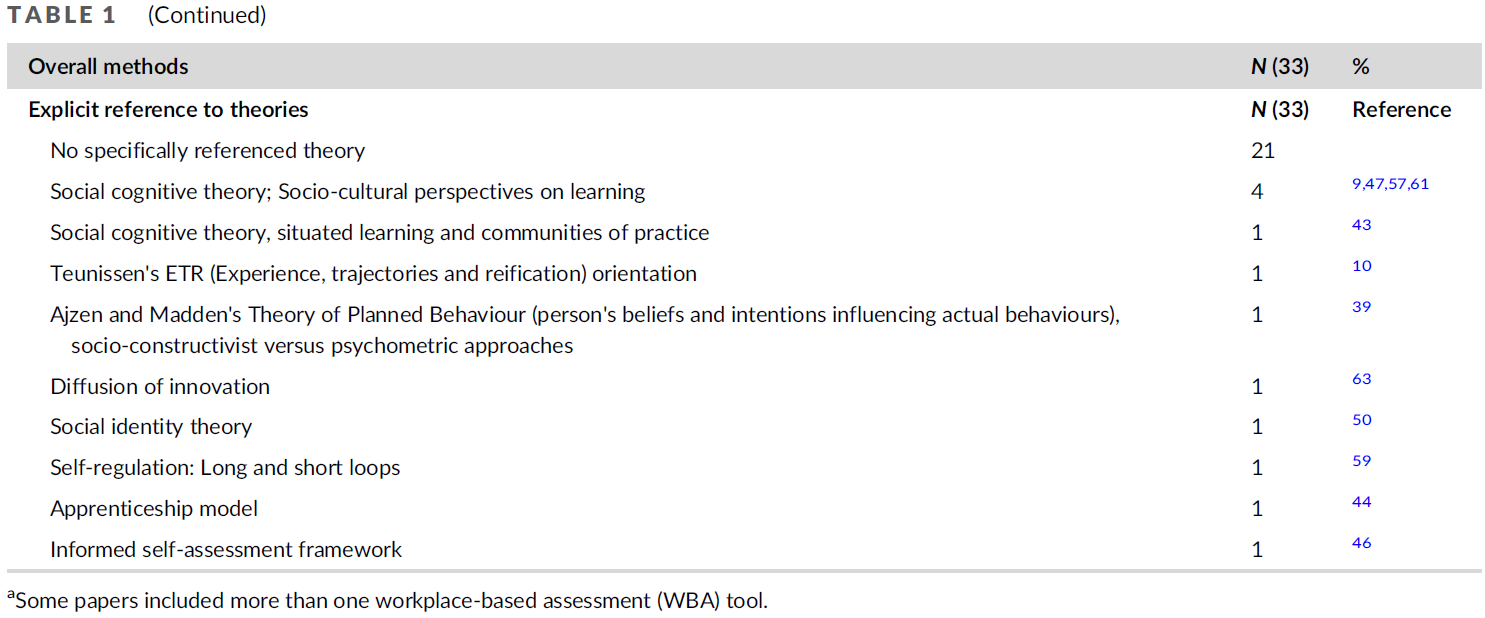

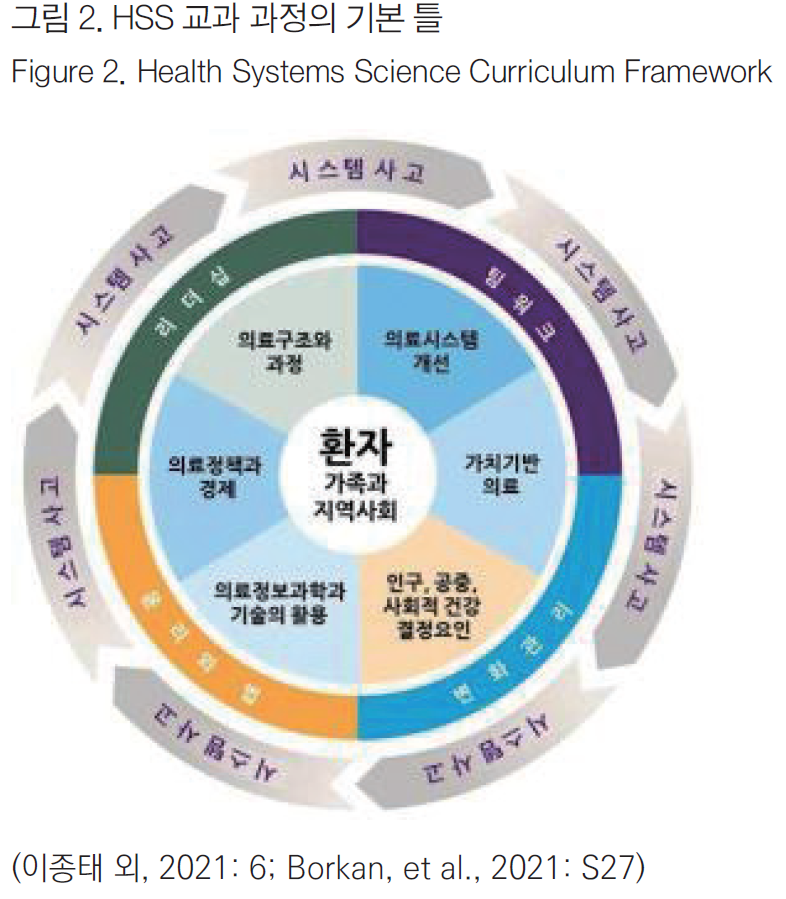

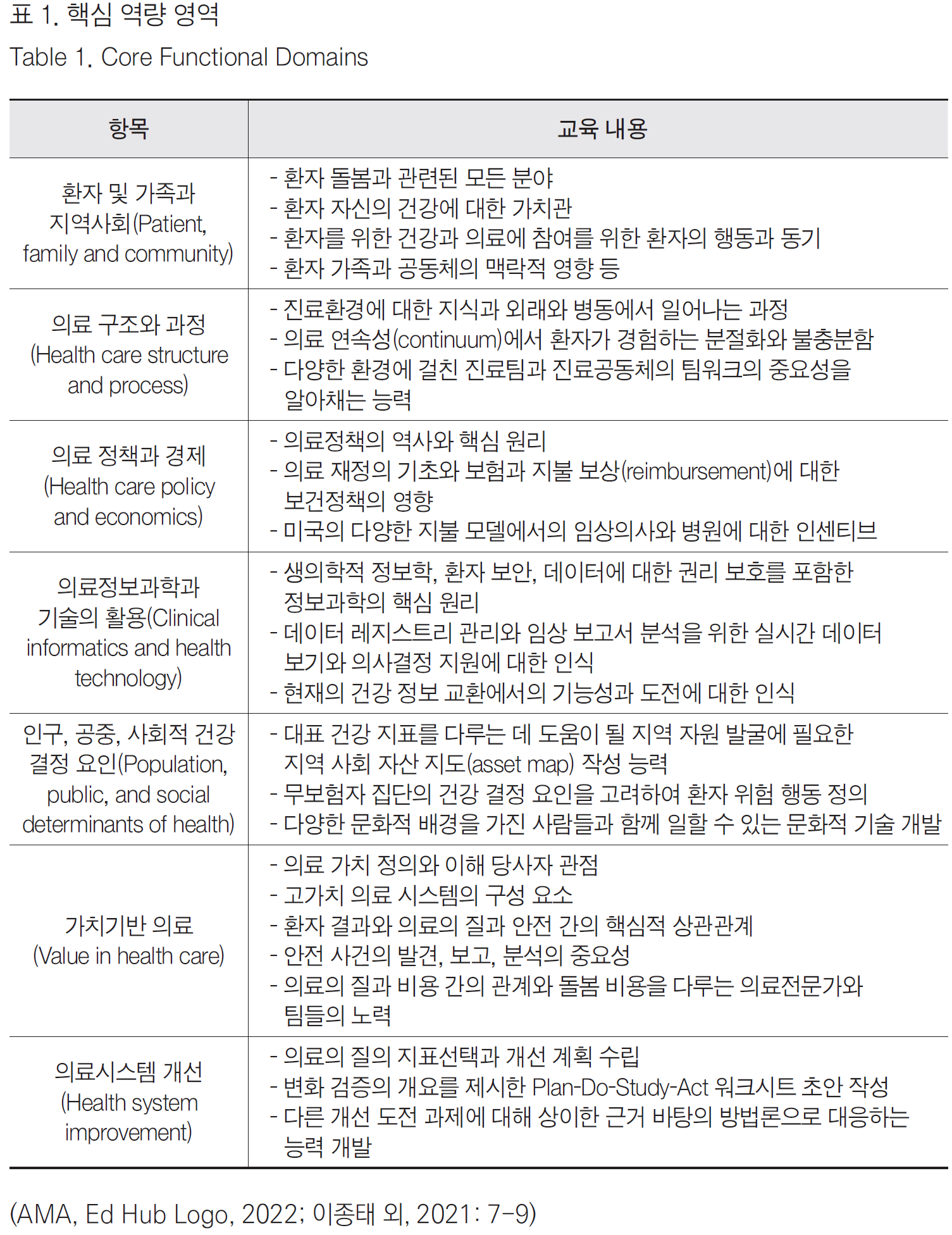

HSS는 <그림 2>에서 볼 수 있듯이 총 12개 구성 요소로 구성되어 있다.

- 이 12개 영역 중 가장 중요한 핵심 영역은 중앙에 있는 ‘환자 및 가족과 지역사회(Patient, family and community)’이다. 그 이유는 ‘환자 및 가족과 지역사회’가 중심이 되는 것이 개인 및 인구를 최적의 상태로 만드는 최고의 추진 동기이기 때문이다.

- “환자 및 가족과 지역사회”를 포함하여 다음과 같이 총 7개 핵심 역량 영역(Core functional domain)으로 구성되어 있다:

- ①환자, 가족과 지역사회,

- ②의료 구조와 과정,

- ③의료정책과 경제,

- ④의료정보과학과 기술의 활용,

- ⑤인구, 공중, 사회적 건강 결정요인,

- ⑥가치 기반 의료,

- ⑦의료시스템 개선.

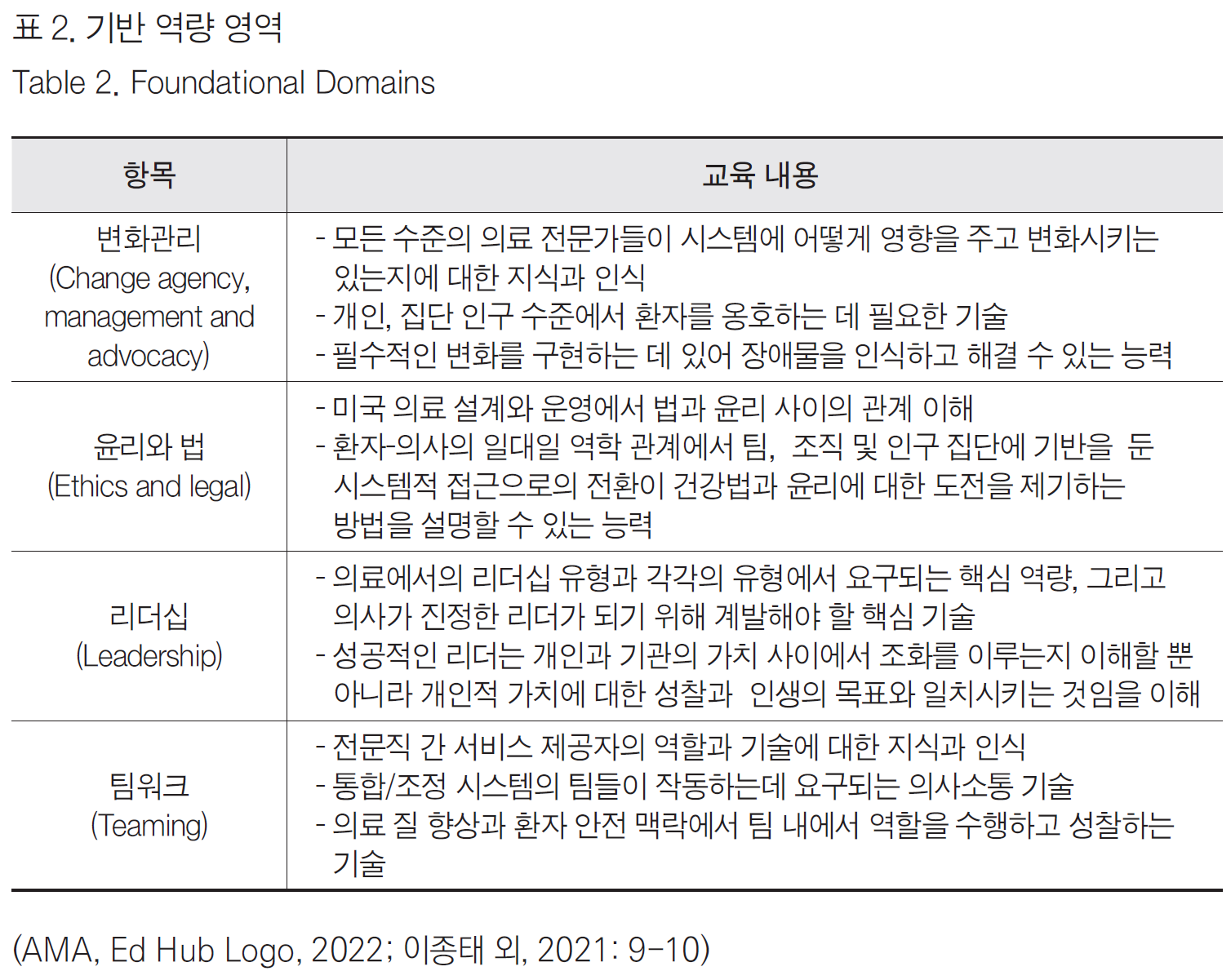

- 이 7가지 핵심 역량을 서로 넘나들면서 다음의 4개의 기반 역량(Foundational domain)이 중간 매개 영역을 담당 한다:

- ①변화관리,

- ②윤리와 법,

- ③리더십,

- ④팀워크.

- 아울러 이 11개 모든 영역은 시스템사고(System thinking)로 연결(Linking domain)되어 총체적으로 통합되어 있다. 여기서 ‘시스템’이란 “공통의 목적을 달성하기 위해 상호 작용하는 상호 의존적인 요소들의 집합”이라 할 수 있다(Dyne, Strauss, & Rinnert, 2002: 1271). 또한 ‘시스템 사고’란 부분이 아닌 ‘전체’를 견지하면서 다방향적 인과관계를 인식하고 해결하는 역량을 의미한다(Skochelak et al., 2021: 8-11; 이종태 외, 2021: 9-10)

의학 분야의 시스템 이론은 1970년대 조지 엥겔(George Engel)에 의해서 제시되었다. 엥겔은 환자-의사 관계의 목표는, “(1)치유 향상, (2)고통 완화, (3)건강을 증진하는 행동과 관련된 격려와 교육”이라고 보았다. 엥겔이 말하는 의학의 생물심리사회적 모델(biopsychosocial model of medicine)에 의하면, 의사는 환자가 가장 많은 정보를 바탕으로 효과적인 의학적 결정을 내릴 수 있도록, 생물학적, 심리적, 사회적, 시스템적 요소를 통합하는 전체론적 접근 방식(holistic approach)을 취해야 한다. 즉 개인은 생물학적 유기체이자, 가족 및 사회적 맥락에서 살아가는 사람으로 간주해야 한다는 지적이다(Skochelak et al., 2021: 7).

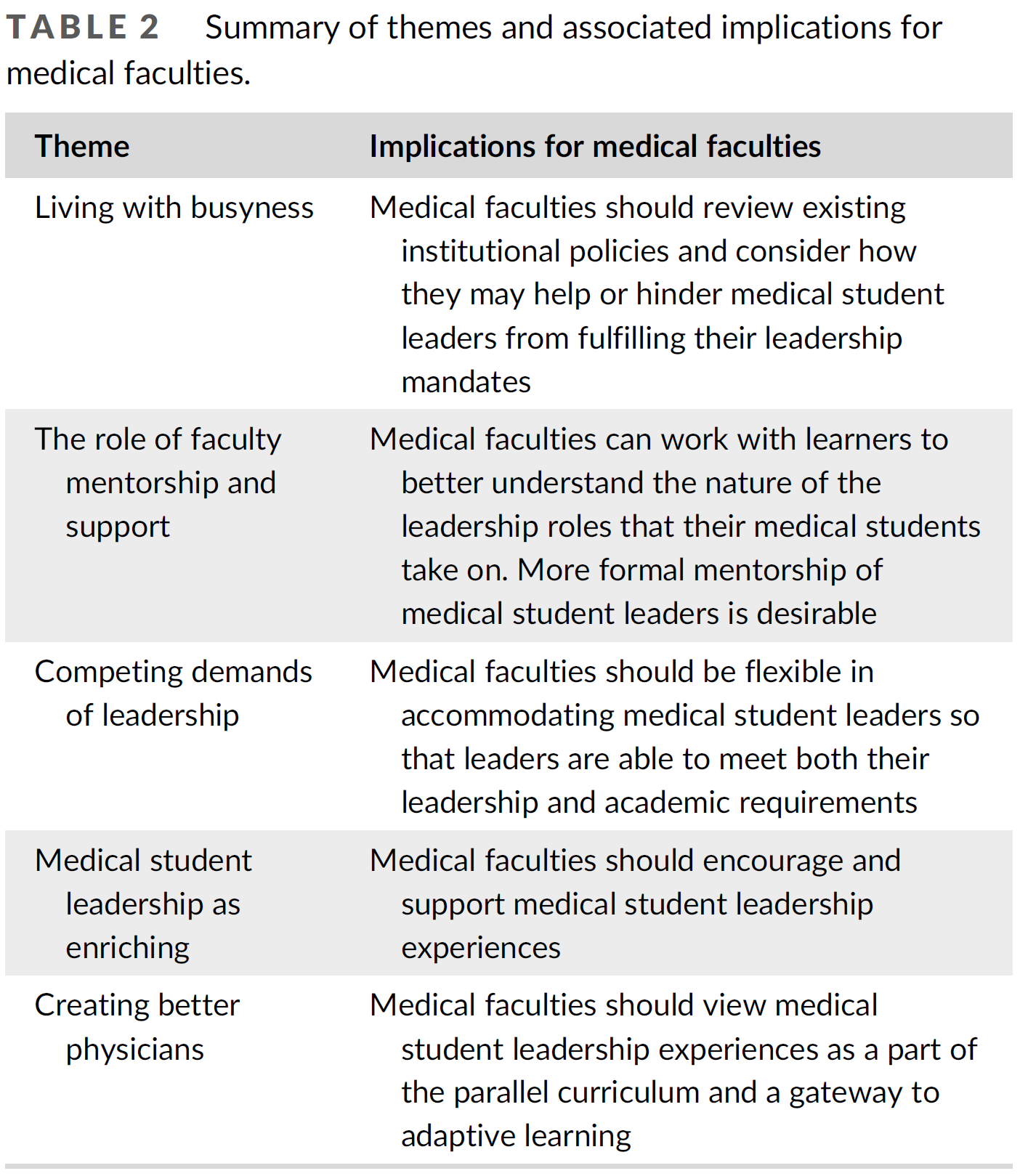

이상과 같이 HSS의 각 영역 간의 관계를 그림으로 표현한 <그림 2>를 보면, 이 기본 틀은 포괄적(comprehensive)인 팀 기반(team-based)의 의사전문직업 정체성 형성(formation of medical professional identity)을 위한 교육 모델이다. 구체적인 내용을 정리한 것이 <표 1>, <표 2>, <표 3>이다.

HSS 식의 시스템 중심 의료체계를 이해하기 위해서는 적정 비용 치료(costappropriate care), 관리의료(managed care)체제2) 에서의 의료 전달체계들(delivery systems)을 최대한 이해하고 활용하는 방법, 환자의 이익 옹호(patient advocacy) 등을 알아야 한다. 예를 들어 응급의학에서 시스템에 기반을 둔 접근을 하자면,

- ①환자 케어 관련된 시스템(보험, 보호자 관련 이슈 등),

- ②기관(병원 등) 관련 시스템,

- ③기술 시스템(운반체제 등),

- ④규제 기관(관련 법 규정 등)을 고려해야 한다(Dyne, Strauss, & Rinnert, 2002: 1271-1276).

이상과 같이 HSS란 7개의 ‘핵심역량,’ 4개의 ‘기반역량’으로 구성되어 있고 ‘시스템 사고’가 이를 아우르고 있다. 다음에는 미국 의학교육에서 HSS 교육 및 적용 현황을 살펴보고자 한다.

===

2) 미국의 관리의료를 간단히 설명하자면, 진료 기록이나 비용 등에 따라 한계선을 정하여 치료를 하도록 하고, 의료 보험에 가입한 사람과 의료 기관 및 의사의 관계를 설정하여 헬스 케어 제도를 총체적으로 관리하는 의료 체계를 의미한다. 대표적인 것이 HMO(Health Maintenance Organization)이다.

===

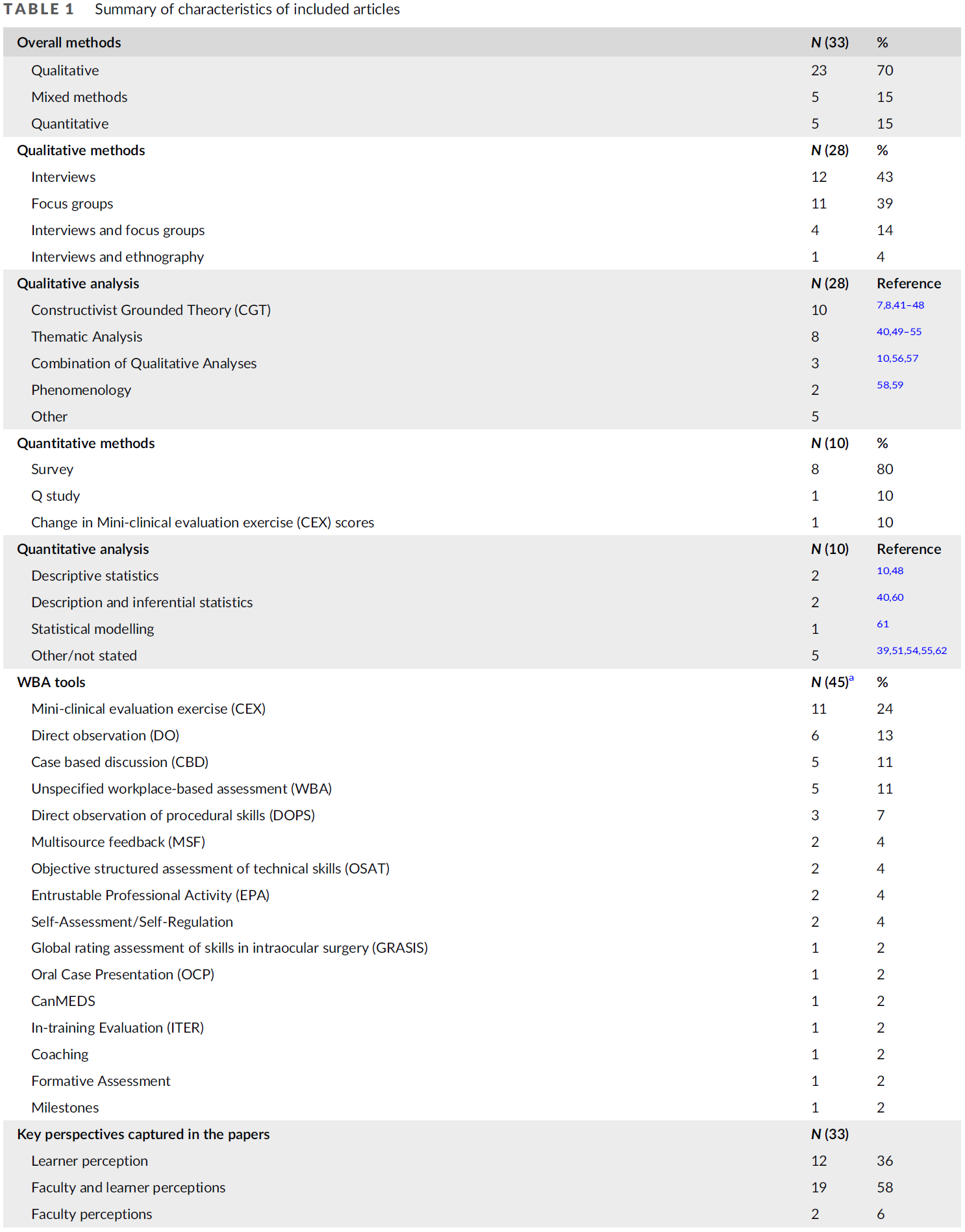

2) HSS의 교육현황

2022년 미국에는 155개 일반 의과대학의 의사(Medical Doctor, MD) 프로그램과 38개 정골의학대학의 정골의학의사(Doctor of Osteopathic medicine, DO) 프로그램이 존재한다. 한국의과대학-의학전문대학원협회에서 발간한 보고서에 의하면 미국 의과대학에서 HSS 운영체계는 크게 세 가지 유형으로 구분할 수 있다.

- 첫 번째 유형은 HSS의 이름 아래 정규 교육과정으로 종단적으로 운영하며 관심 있는 학생들을 위해 선택과목으로 추가적인 과정을 운영하는 대학들이다. 대표적으로는 펜실베이니아 주립의과대학(Pennsylvania State University College of Medicine), 이스트 캐롤라이나 브로디의과대학(ECU Brody School of Medicine), 워렌알포트 브라운 의과대학(Warren Alpert School of Medicine of Brown University), 인디애나 의과대학(Indiana University School of Medicine) 등이 있다.

- 두 번째 유형은 HSS의 주제와 내용이 부각되는 새로운 정규과정을 개설하였지만, 첫 번째 유형과 다르게 특별 과정은 따로 두지 않는 경우이다. 두 번째 유형에는 캘리포니아 샌프란시스코 의과대학(UCSF School of Medicine), 메이요 클리닉 앨릭스 의과대학(Mayo Clinic Alix School of Medicine), 미시간 의과대학(University of Michigan Medical School), 뉴욕대 그로스먼 의과대학(NYU Grossman School of Medicine), 밴더빌트 의과대학(Vanderbilt School of Medicine) 등이 있다.

- 세 번째 유형은 HSS라는 과정명은 없지만, 다른 교과목과 함께 통합하여 기존 교육 과정에 융합한 대학이다. 세 번째 유형에는 캘리포니아 데이비스 의과대학(UC Davis School of Medicine), 오레곤 보건과 과학대학 의과대학(Oregon Health and Science University Medical School) 등이 있다(이종태 외, 2021: 15; Skochelak et al., 2021: 304).

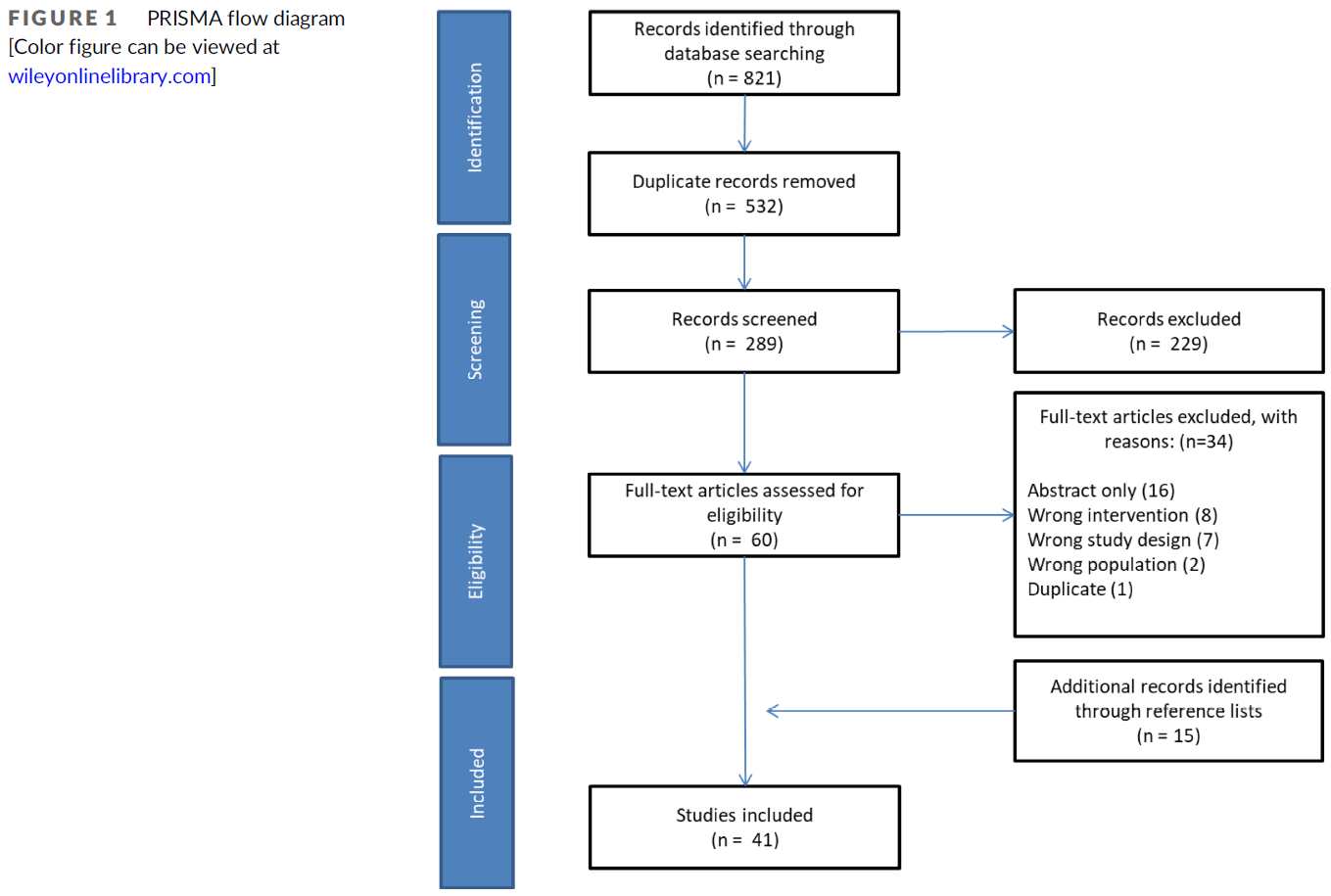

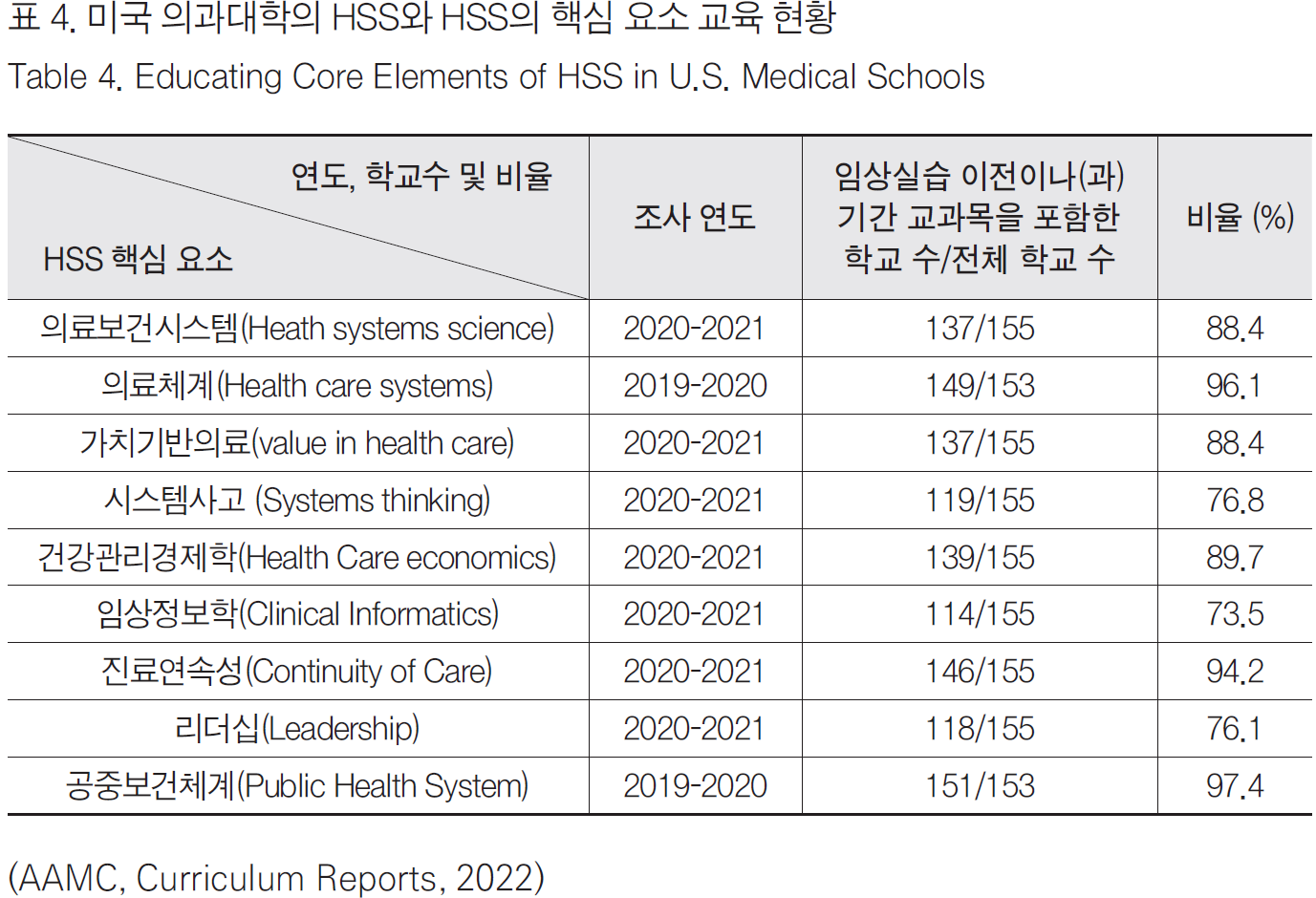

이 대학들 외에도 실제로 교과 과정에 HSS 교과목을 필수과목이나 선택과목으로 가르치고 있는 대학들이 있다. 2019-2020년 통계에 의하면 임상실습 이전에 전체 의과대학의 83.2%인 129개 대학, 임상실습 중에는 전체의 69.7%인 108개 대학에서 교육하고 있다. 그 외에도 HSS의 12개의 핵심 요소에 대해서 가르치는 대학의 수도 상당수이다.3) 이를 표로 정리하면 <표 4>와 같다.4) 또한 미국 면허시험(United States Medical Licensing Examination)과 전국의사면허시험원(National Board of Medical Examiners)에서는 HSS에 대한 시험 과목과 문제를 개발하고 있다(Skochelak et al., 2021: 16).

===

3) 본 연구에서는 명시적으로 HSS의 핵심요소를 표시한 경우만 다루고 있다. 그러나 실제로 연관 분야로 교과 과정에 포함한 경우까지 포함하면 더 많을 것이다. 예를 들어 의료 재정(health care financing)과 같이 의료경제(healthcare economics)에 포함될 수 있는 경우에도 본 연구에서는 포함하지 않았다.

4) 조사 연도의 경우, 가장 최근에 조사된 기록이다. 비율은 소수점 둘째 자리에서 반올림한 숫자이다.

===

HSS 구조틀은 이전에 흩어져 있던 학습 영역의 통합을 제공하여서, 의료 분야에서 변화하는 의학전문직업성에 대한 총체적인 관점을 만들어냈다. 즉, 기존에는 질 개선, 의료 제공, 보건 구조적 및 사회적 결정 요인, 고부가가치 의료와 같은 시스템에 기반을 둔 이슈는 모두 따로따로 학습됐다. HSS는 이런 분절된 요소들을 통합하여 시스템적 요소들과 함께, “기초-임상-HSS”의 삼각 구조를 형성하였다.

이상과 같이 2013년부터 AMA가 사회 변화에 따른 보건의료의 요구를 충족하기 위해서 기존 기초의학과 임상의학 개념에 더하여 ‘제3의 의학’으로 HSS를 도입하였다. 이후 미국 의과대학 상당수에서 HSS나 연관 교과목을 교육하고 있다.5) 다음 2개의 장에서 1910년대부터 1960년대, 1960년대부터 2010년대까지 의료 개혁의 노력과 사회적 변화, 그리고 이에 따른 의학 교육계의 변화를 역사적으로 추적하고자 한다.

===

5) 그러나 HSS를 학생들에게 교육하는데 큰 방해물이 있다. 환자 중심의 시스템적 접근을 하는 HSS 교육이 중요함에도 불구하고, HSS 교육 내용이 미국 면허시험에 대다수 채택되지 않았기에 학생들과 교수진은 HSS를 핵심 교육이 아닌 ‘주변적인 교과 과정’으로 여기는 경향이 강하다(Gonzalo, et al., 2016).

===

3. 의료 개혁

역사적으로 미국의 의료제도는 전형적으로 ‘환자-의사’ 양자 관계에 기반을 둔 사적 영역(private sector)으로 발전해 왔다. 식민지 시기부터 미국의 지배적인 문화는 ‘앵글로 색슨-개신교 청교도주의(Anglo-Saxon puritanism)’ 문화였다. 개신교는 성직자의 중개 없이 성경에서 직접 하나님의 말씀을 받고 은총을 받아 구원을 얻거나 거듭나야 한다는 믿는 종교이다. 이러한 종교적, 사회적 분위기는 개인주의 전통을 낳았다. 또한, 개인의 재능과 성품, 노력에 따라 사회적 성공에 이른다고 믿는 ‘아메리칸 드림’의 중심적 요소가 되었다. 이러한 문화 속에서 ‘공짜로 무언가를 얻는 것’은 ‘시민됨(citizenship)’에 어긋나는 것으로 여기며, 복지의 책임이 국가와 사회보다는 개인과 가족에게 있다는 자조의 이념이 선호되었다. 이런 이념 아래에서는 미국식 복지의 개념 역시 제한적일 수밖에 없었다. 또 원칙적으로 어느 분야를 막론하고 시장과 자유경쟁 원리에 따르기 때문에, 정부의 기본적인 역할은 주도적이기보다는 보완적이었다. 이에 건강 보장 역시 개인주의에 바탕을 둔 시장 기제를 선호하였다. 전통적으로 미국에서 의료는 공공재가 아닌 사적 영역으로 소비자의 선택권을 최대한 보장하는 ‘소비자 주권형(consumer sovereignty model)’에 속해왔다(김성수, 2018: 108-114; 119). 그러나 20세기 초반에 이르면 혁신주의(Progressivism)6) 정치가와 사회개혁가들이 공공복지에 대한 정부의 책임성을 강조하는 의료 정책과 전 국민 의료보험에 대한 논의를 전개하였다. 이러한 노력은 100년이 훨씬 지난 후에 결실을 이룰 수 있었다.

===

6) 20세기 초부터 1917년도까지 중산층의 주도하에 미국에서 전개된 광범위한 정치 · 사회개혁 운동을 말한다.

===

1) 1910년대에서 1960년대까지의 변화

19세기 말 독일의 공적 의료보험7) 도입을 목격한 미국 혁신주의자들은 1915년 ‘미국노동법협회(American Association for Labor Legislation, AALL, 1906-1945)’를 통해 전국민 건강보험 도입을 위한 활동을 본격적으로 시작했다. 1915년 AALL은 8개 주에서 ‘강제건강보험제도(compulsory health insurance)’를 입안하려고 시도하였다. 이 시도의 초창기에는 AMA의 승인도 얻어냈었다. 그러나 1917년 러시아의 볼셰비키 혁명(공산주의 혁명)과 미국의 제1차 세계대전에의 개입 때문에 AMA는 기존의 태도를 바꾸어 강제건강보험 제도에 반대 견해를 강력하게 표명하였다. AMA는 강제건강보험이 도입되면 당시까지 의학계에서 독점해 온 진료와 의료비에 대한 통제력을 상실할 것이라는 우려에 휩싸였다. 이와 동시에 주 에서도 강제건강보험 논의 역시 인기를 잃어 결국 성공하지 못했다. 1920년대에는 ‘의료돌봄비용위원회(Committee on the Costs of Medical Care, 이후 국가보건위원회[Committee for the Nation’s Health]로 변경)’에서 그룹 의료(group medicine)와 자발적 의료보험(voluntary insurance)을 제안했지만, AMA는 이는 ‘사회주의 의료(socialized medicine)’라는 비난으로 맞대응을 하였다(Birn et al., 2003: 86-87).

===

7) 독일에서는 일찍이 19세기 말 1880년대부터 오토 폰 비스마르크(Otto Eduard Leopold Fürst von Bismarck-Schönhausen)가 노동자질병보험법(1883)과 재해보험법, 제국보험법(1911) 등을 입법화시키면서 근로자들의 질병, 업무상 재해, 장애 및 노령 위험으로부터 보호할 수 있는 체계를 마련하였다. 이 법안들은 독일 최초로 전국을 대상으로 하는 공적 건강보험제도의 도입을 의미하였다(황도경, 2013: 57-59).

===

1930년대 대공황시기(Great Depression)에 강제건강보험에 대한 논의는 다시 일어났다. 경제 대공황으로 인한 소득불균형은 의료접근성의 불균형을 초래하였다. 대공황이 한창이던 1934년 프랭클린 D. 루스벨트(Franklin D. Roosevelt) 대통령은 ‘경제보장위원회(Committee on Economic Security)’를 통해 노인 문제, 실업문제, 의료 및 건강보험(강제건강보험)에 대한 안건을 ‘뉴딜정책(New Deal proposals)’8)과 함께 상정하였다. 그러나 전국민건강보험과 관련된 사항은 최종 입안된 「사회보장법안(Social Security Bill)」에 포함되지 않았다(Hoffman, 2003: 76; 여영현 외, 2018: 213). 1930년대에 접어들어 AMA의 정치적 영향력이 더욱 확대되었고, 이들은 여전히 국가건강보험에 반대했다. AMA는 자신들의 궁극적인 관심은 시민의 복지와 건강유지 및 질병 치료, 의학발전에 있다고 하면서, 자신들이 개인 건강보호에 관한 한 유일한 국가이익의 수호자임을 자처하였다(Rimlinger, 1991: 315). 1939년부터 ‘사회보장위원회(Social Security Board)’에서는 ‘전국보건프로그램(National Health Program)’의 내용을 포함하기 시작하였다. 1942년 사회보장이사회는 보건 혜택을 포함한 포괄적인 사회보장제도를 제시하였다. 1942년 연방의회에서는 군인 가족에 대한 건강보험 체계인 ‘긴급모자케어(Emergency Maternity and Infant Care)’를 승인하였다(Hoffman, 2003: 76).

===

8) 실업자에게 일자리를 만들어 주고, 경제 구조와 관행을 개혁해 대공황으로 침체된 경제를 되살리기 위해 추진한 경제 정책이다.

===

한편 제2차 세계대전이 한창이던 1943년 ‘국가전시노동이사회(National War Labor Board)’는 임금 및 물가 통제라는 명목으로 건강보험을 포함한 특정 근로혜택을 제외해야 한다고 결정하였다. 이 결정 이후 대신 고용주들은 근로자들을 채용하기 위해 집단건강보험을 강화하였다. 이때 ‘전국민강제가입 건강보험’을 주장하고 나온 것이 「와그너-머레이-딩겔 법안(Wagner-Murray-Dingell bills)」이었다. 그러나 AMA는 ‘의료서비스 확대를 위한 전국의사위원회(National Physicians’ Committee for the Extension of Medical Service),’ ‘미국보험경제학회(Insurance Economics Society of America),’ ‘제약회사협회(Pharmaceutical Manufacturers’ Association)‘ 등과 함께 정부 주도의 건강보험에 반대하였다(Hoffman, 2003: 76-77). AMA 외에도 또 다른 이익집단인 ‘미국병원협회(American Hospital Association, AHA)’가 건강보험 논쟁에 참여하게 되었다. AHA는 건강보험 도입에 대해 기본적으로 AMA보다 유연한 태도를 보이면서, 이들은 건강보험 도입이 궁극적으로 병원의 이익에 부합할 것이라는 전제하에 국가 또는 공적 영역에서가 아닌 비영리조직 또는 시장 영역에서 건강보험을 도입하는 안을 발전시켰다. 그 후 AHA는 사적 건강보험의 효시라 할 수 있는 ‘블루크로스(Blue Cross)’9)를 탄생시켰다(김태근, 2017: 42). 이 보험은 병원과 진료소 등 자체 공급구조로 되어 있었고 일정액의 보험료를 받고 정해진 모든 서비스를 제공하는 ‘정액 보험료-포괄적 서비스’방식을 택했다. 이처럼 기존의 민간 보험과는 다른 건강보험은 기업들이 노동자에게 건강보장을 제공하는 것을 더 쉽게 하였다. 이것은 1970년대 이후 미국 건강 보장의 주된 방식으로 등장하는 이른바 관리의료의 기본 틀을 제공하였다(김성수, 2016: 80).

===

9) 블루크로스는 입원보험, 블루쉴드(Blue Shield)는 진료보험을 말한다. 이것들은 계약 병원이나 계약 개업의를 통해서 의료서비스를 제공하는 방식이다. 블루크로스는 1929년 텍사스(Texas) 댈러스(Dallas)시에서 창설되어 학교 교원집단과 베일러(Baylor)대학병원 간의 계약에 따라 교원 1인당 연간 6달러 정도의 보험료로 병원에서 주는 개인 병실에서 21일간 입원 급여를 보장하는 것이었다. 블루쉴드는 1939년 캘리포니아(California) 의사회에서 최초로 설립하여 1946년 각 지방 조직을 조정하기 위한 블루쉴드 연합회가 조직되었다. 블루크로스와 블루쉴드는 1982년 완전히 통합되었다. 이후 블루크로스-블루쉴드 가입자에게 의료서비스를 현물급여방식으로 제공하며 그 비용을 병원이나 의사에게 지급하고 있다. 이 방식은 영리를 목적으로 민간건강보험이 가입자에게 직접 지급하는 상환불 방식과 다르다(김성수, 2016: 85-86).

===

제2차 세계대전 이후인 1945년 개혁가들은 주 정부가 운영하는 강제건강보험에서 한층 더 나아가 미국인 모두를 포함하고, 보편적이며 종합적인 ‘전국민건강보험(National Health Insurance, NHI)’을 사회보장의 하나로 제안하였다. 루스벨트 대통령은 전쟁 이후에 건강보험 혜택을 확대해야 한다고 주장하였으며, 후임인 해리 S. 트루먼(Harry S. Truman) 대통령은 1948년 재선 이후 ‘공정 정책(Fair Deal)’의 하나로 모든 미국인에게 혜택을 주는 단일 건강보험 프로그램을 주장하며, 의회에 전국민건강보험의 통과를 요구하였다. 트루먼 대통령이 제안한 전국민건강보험 안에는 저소득층에게 ‘공적 보조금(public subsidy)’을 주는 방안이 포함되어 있었다(Gordon, 1997: 277-310). 그러나 AMA는 100만 달러를 반의료개혁운동에 투자하였고, 「와그너-머레이-딩겔 법안」의 통과도 막아냈다. 1940년대 말로 넘어가면서 미국 사회는 급격히 냉전과 반공 이데올로기로 뒤덮이게 되었고, 의회는 ‘매카시즘(McCarthyism)’10)의 광풍에 휩싸이게 됐다. 그러면서 국민건강보험 법안을 비롯한 모든 진보 정책은 의회와 행정부에서 설 자리를 잃게 되었고, 국민 건강 보장 운동은 ‘사회주의 의료’로 낙인찍혔다. 한편 고용주와 노조는 직장에 기반을 둔 민간 의료보험을 지지하였고, 개별적인 사적 보험에 의지하는 일이 늘어났다(Hoffman, 2003: 77).

===

10) 1950년부터 1954년까지 미국을 휩쓴 공산주의자 색출 열풍을 말한다. 보통은 1940년대 말부터 1950년대 말까지 ‘제2차 적색 공포(Red Scare) 시대’의 정치적 행위를 일컫는다.

===

이상과 같이 1910년대 혁신주의는 전 국민 의료보장에 대한 논의를 불러 있으켰다. 그러나 제1차 세계대전, 1920-1930년대와 제2차 세계대전을 겪으면서 NHI에 대한 논의는 큰 진전을 보지 못했다. 의료 체계의 개혁 노력은 1960년대에 다시 본격화되었다.

2) 1960년 이후부터 오마바케어까지의 변화

1960-70년대는 미국 사회와 의료에서 큰 변화를 초래하였다. 존 F. 케네디(John F. Kennedy) 행정부와 린든 B. 존슨(Lyndon B. Johnson) 행정부에서 1960년대 노인층을 위한 건강보험 계획을 추진하였다. 1960년 연방의회는 「커-밀즈 법안(Kerr-Mills Act)」으로 더 유명한 「노인 의료부조법(Medical Assistance for the Aged Act)」을 통과시켰다. 이 법안으로 각 주 정부는 연방정부의 재정지원으로 저소득층 노인들에게 건강보험을 제공할 수 있게 되었다. 그러나 이 법안이 도입된 지 3년이 지난 1963년까지도 단지 과반이 넘는 주만 이 법안을 시행한다고 서명하였다. 무엇보다 이 법안의 시행에는 재정적 어려움이 뒤따라 실질적 시행에서는 성공적이지 못했다(Iglehart, 1999a: 70-76; 327-332; 여영현 외, 2018: 205).

존슨 대통령은 1965년에 기존의 사회보장 프로그램을 개정한 ‘메디케어(Medicare)’라는 노인을 위한 사회건강보험을 신설하였다. ‘AFL(미국노동총연맹, America Federation of Labor)-CIO(산업별노동조합회의, Congress of Industrial Organization)’는 은퇴한 조합원들로 구성된 ‘전국노령시민회(National Council of Senior Citizens)’를 만들어서 메디케어의 시행을 강하게 지지하였고 다른 은퇴한 직업군도 함께 참여하도록 독려하였다(Iglehart, 1999b: 327-332). 같은 시기에 시행된 ‘메디케이드(Medicaid)’는 정부가 재원 조달과 관리를 담당하는 건강보장제도라는 점에서 사회보험과 정부 지원이 혼합된 메디케어와 구분이 되었다. 즉 메디케이드는 빈곤층에게 의료서비스를 제공하는 연방정부(법령, 규칙 등으로 일관성 기여)와 주 정부(재정 조달)의 공동 프로그램이었다(Iglehart, 1999c: 403-408).

노인들과 노동계에서 주도한 ‘전국건강보험위원회의(Committee for National Health Insurance)’는 AMA의 제안서를 포함한 다른 13개의 건강보험제안과 함께 경쟁해야만 했다. 1970년대에 의료비가 비싸지면서 대중의 관심은 보험 커버의 확대보다는 비용 절감에 쏠리게 되었다. 1973년 연방정부에서는 관리의료체계인 ‘건강관리기구(Health Maintenance Organization, HMO)의 확산을 촉진하기 위해 「연방 HMO법(Federal Health Maintenance Organization Act of 1973)」을 제정하였다. 리처드 M. 닉슨(Richard M. Nixon) 대통령은 1974년 자신의 ‘종합건강보험안(Comprehensive Health Insurance Plan)’을 통해 고용자의 참여가 필요한 건강보험안을 내놓았다(여영현 외, 2018: 216). 한편 AMA는 이에 대한 반대 로비를 지속하였다. 법안에 대한 논의가 진행되던 중 워터게이트(Watergate)11) 청문회 때문에 닉슨 대통령이 물러나게 되면서 논의는 더 진전되지 못했다. 닉슨 대통령의 후임으로 제럴드 R. 포드(Gerald R. Ford, Jr.) 대통령이 취임한 후 NHI 법안은 다시 탄력을 받게 되었으나 합의를 이끌어 내지 못하였다(여영현 외, 2018: 217). 1970년대 내내 지속적인 경기불황, 물가상승, 높은 실업률 등 때문에 포드 대통령은 NHI가 물가상승을 더욱 부추길 수 있다는 이유로 NHI에 관한 논의를 중단하였다. 지미 E. 카터(Jimmy E. Carter, Jr.) 대통령은 자신의 선거공약으로 NHI를 다시 내세웠으나, 경제침체 탓에 의회의 다른 의제에 밀리게 되었다(김성수, 2016: 140). 1982년 로널드 W. 레이건(Ronald W. Reagan) 행정부는 메디케어 수혜자의 증가에 따른 지속적인 의료비 상승의 속도를 둔화시키기 위해 메디케어 입원환자의 지급방식을 ‘행위별 수가제(Fee-for-service, FFS)’에서 ‘포괄수가제(Diagnosis-related group, DRG)’에 기초한 ‘선불 상환제도(prospective payment system, PPS)’로 전환했다(여영현 외, 2018: 218).

===

11) 워터게이트 사건(Watergate scandal)은 1972년부터 1974년까지 2년 동안 닉슨 행정부가 베트남전 반대 의사를 표명했던 민주당을 저지하려는 과정에서 일어난 불법 침입과 도청 사건, 그리고 이를 부정하고 은폐하려는 미국 행정부의 조직적 움직임 등 권력 남용으로 말미암은 정치 스캔들이었다. 닉슨은 탄핵안 가결이 확실하게 되자, 1974년에 대통령직을 사퇴하였다. 이로써 닉슨은 미국 역사상 최초이자 유일하게 임기 중 사퇴한 대통령이 되었다.

===

한편 1992년 대통령 선거가 다가오자 당시 민주당 대선 후보였던 빌 J. 클린턴(Bill J. Clinton) 대통령은 NHI를 역설하였다. 클린턴은 대통령에 당선된 후 부인인 힐러리 클린턴(Hillary Clinton)과 대통령의 의료정책 고문(chief healthcare policy advisor)이었던 아이라 매거진너(Ira Magaziner)를 중심으로 ‘국가의료개혁대책위원회(Task Force on National Health Care Reform)’를 구성하였다. 결국 ‘관리경쟁(managed competition)’12)에 기초하여 민간 중심의 시장 기전을 이용하고 고용자가 피고용자에게 건강보험을 의무적으로 제공하는 것을 골자로 하여 전 국민에게 건강보험을 제공하는 「건강보장법(Health Security Act)」이 만들어졌다. 이 법안은 의료보장을 정부가 정하는 기본 원칙 아래에서 전 국민에게 같은 방법으로 적용하되, 서비스 제공이나 비용통제는 시장의 경쟁원리에 맡긴다는 내용이었다. 지역별로 구매자 조직인 ’건강 연합(health alliance)’을 만들어 보험료로 재원을 조달하고 집단으로 민간보험을 구매하는 역할을 하게 하자는 것이 제안의 뼈대였다. 이것은 ‘전국민건강보험(Universal health insurance)’을 도입해 미국 내 모든 합법적 거주자들이 의료보험을 보유하도록 하는 것이었다. 또한, 이 법안은 ‘국립보건위원회(The National Health Board)’라는 연방 기구(Federal agency)를 신설해 보험료와 의료 수가를 국가 주도하에 통제하는 것을 목표로 하였다. 1년여에 걸쳐 수많은 공청회와 상임위원회 토론, 그리고 원외에서의 거듭된 여론전이 있었음에도, 대중과 이익단체로부터 호응을 얻지 못하고 1994년 11월 상원에서 최종적으로 폐기되었다. 결국 클린턴 행정부의 보건의료 개혁은 실패로 돌아갔다(Hoffman, 2003: 78). 1997년 타협안으로 메디케이드 자격은 되지 않으나 민영건강보험을 이용하기 어려운 저소득 계층 아동의 보호를 위한 ‘어린이건강보험프로그램(State Children Health Insurance Program, SCHIP)’을 제정하게 되었다. SCHIP은 1965년 메디케이드 제정 이후 어린이들의 건강보험을 보장해주는데 가장 큰 영향을 미친 프로그램이었다(여영현 외, 2018: 220).

===

12) 관리의료의 한계성을 극복하려는 노력으로 관리경쟁(managed competition)이 등장하였다. 이것은 고용자와 소비자에게 최대한의 가치를 제공하는 구매전략으로, 의료서비스 후원자(고용자, 정부, 의료서비스 구매조합 등)가 다수의 건강보험 가입자들을 대신하여 가격 경쟁을 회피하고자 하는 보험회사를 견제하기 위해 의료 시장을 재구성하고 조정하는 것을 의미한다(여영현 외, 2018: 219).

===

클린턴 행정부의 실패 이후 20여 년 가까이 흐른 뒤, 민주당이 대통령과 상-하원 의원 다수를 차지한 버락 H. 오바마(Barack H. Obama) 대통령 때 드디어 전 국민 의료보험 법안을 통과시켰다. 오바마는 당선 후 2009년 2월 SCHIP의 보장성 확대 법안을 통과시키고, ‘오바마케어’로 알려진 「의료보험개혁법(H.R. 4871)」을 2010년 3월에 통과시켰다. 오바마케어의 가장 큰 목적은 미국 인구 중 보험 가입이 되어있지 않은 인구의 보험 가입을 촉진하고, 의료비용을 감소시키는 것이다. 이 법은 10개의 장으로 구성되어 있고, 총 2천 페이지가 넘는 방대하고 복잡한 내용을 담고 있었다.

오바마케어의 주요 내용을 정리하면 다음과 같다.

- 첫째는 전국민건강보험 제도의 성립이다. ‘개인 의무(Individual mandate)’라는 모든 시민이 의료 보험에 가입해야 한다는 체계를 도입했고, 이를 위반하면 벌금13)이 부과된다. 의료 보험 의무 가입 대상은 서류미비자, 불법이민자, 저소득층 등을 제외한 모든 시민권자와 영주권자14)이다. 전국민건강보험을 이루기 위해 오바마케어가 취한 정책수단은 미가입자에 대한 벌금 부과와 일정 소득 이하 자에 대한 확장된 지원 프로그램이다.

- 둘째, 보험 가입을 쉽게 하려고 ‘건강보험거래소(insurance exchange)’를 설립해서, 이를 통해 개인이 자신에게 가장 적합한 보험 계획을 선택할 수 있다는 점이다. 보험료를 낮추기 위하여 온라인 건강보험 상품거래소를 설치하여 모든 의료보험 상품을 한 번에 비교할 수 있도록 하고 있다. 이들 상품은 기본적인 의료혜택을 포함하고 있어야 하고, 가입을 거부하거나 중도 취소할 수 없도록 하고 있다. 보험거래소를 이용하는 것이 정부보조를 받을 수 있는 유일한 방법이기에 모든 의료보험 가입은 이곳을 통해 이루어진다.

- 셋째, ‘보험 혜택 확대(essential health benefits)’를 통하여 기존 병력이나 노령 등을 이유로 의료보험회사가 보험가입을 거부하거나 강제 해지 또는 높은 가산금을 내도록 하는 걸 금지하는 것이다. 보험 회사들이 제공해야 하는 최소한의 건강 보험 혜택을 정의하고, 이를 모든 보험 계획에 적용하도록 요구하고 있다. 보험혜택의 등급(플래티넘, 골드, 실버, 브론즈)을 나눌 수 있지만, 기본적인 의료혜택은 어떠한 등급에서도 제공되어야 한다고 규정하고 있다. 기본적인 의료혜택에는 외래환자 진료, 응급 서비스, 입원, 임산부 및 신생아 진료, 정신 건강 및 약물 남용 장애 치료, 처방 약, 재활 및 훈련 서비스 및 장비, 실험실 서비스, 예방 및 건강 서비스와 만성질환 지원, 아동 서비스(치과와 안과 진료 포함)가 있다.

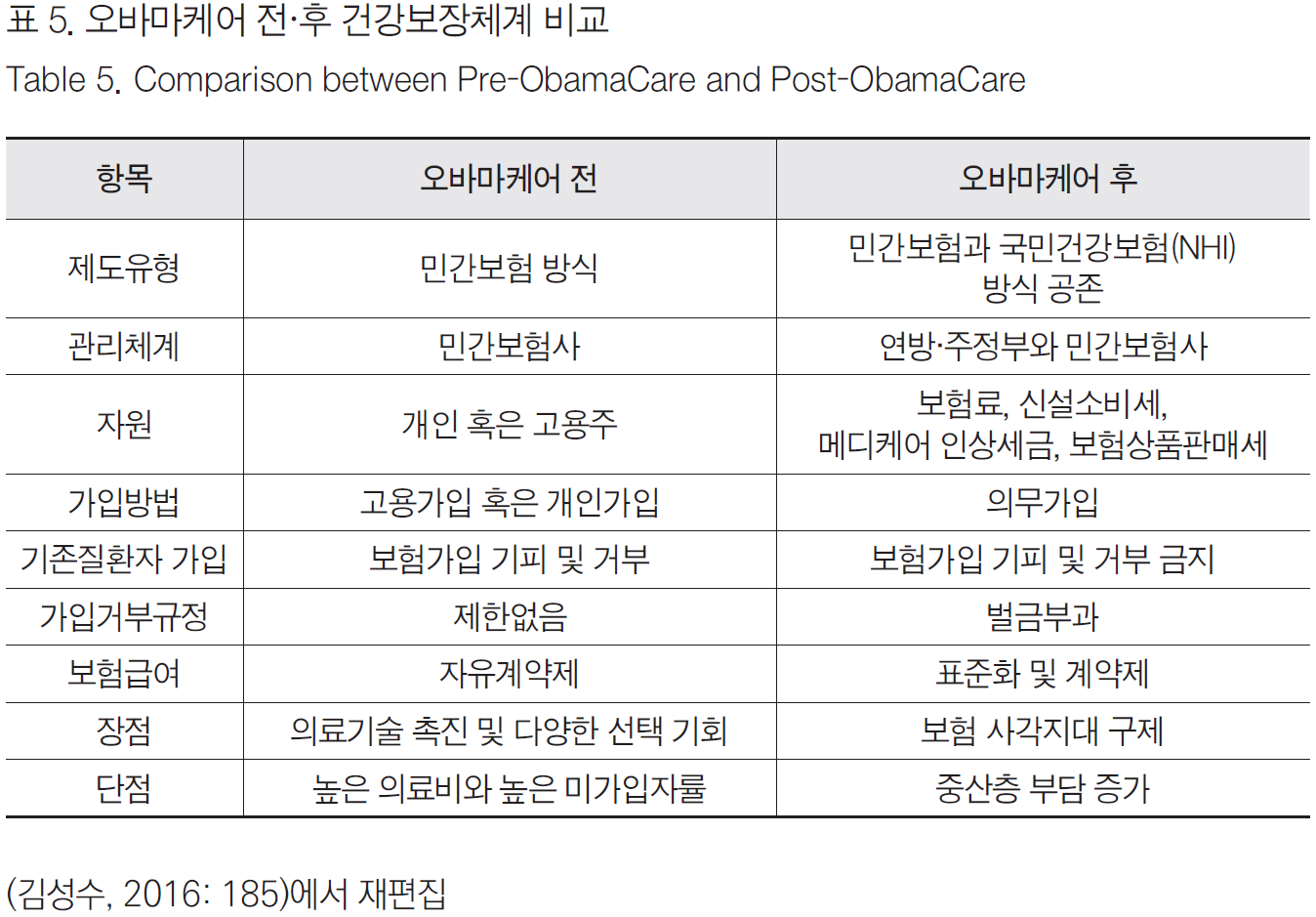

- 넷째, 정부가 설치한 온라인 건강보험 상품거래소에서 제공하는 보험 상품에 ‘정부보조금(subsides)’을 주는 방식이다. 소득이 낮은 가정이 보험 가입을 할 때 지급하는 보험료를 지원하고 있다. 이러한 오바마 케어를 통한 건강보험 개혁으로 <표 5>와 같은 변화가 일어났다.

===

13) 대상은 개인과 기업으로 나누어 볼 수 있다. 개인은 의무가입 대상이 미가입할 경우 당장 다음 해부터 벌금을 내야 한다. 내야 하는 벌금은 시행 다음 해인 2014년에는 연간 95달러 또는 소득의 1%중 큰 액수, 2년 후인 2015년에는 325달러 또는 소득 2%로 매년 증가한다. 기업 중 주당 30시간 이상 전일제 직원이 50인 이상인 기업은 의무가입 대상으로 미가입 시 벌금이 있다. 직원 수가 적은 기업이 의료보험을 직원에게 제공하면 세제 혜택을 제공하도록 하고 있다.

14) 영주권을 취득한 지 5년 이상 지난 자를 대상으로 한다. 단, 아동과 임산부는 영주권 취득 후 5년이 지나지 않아도 의료보험 혜택을 받을 수 있다.

===

오바마케어 이후 미국의 의료 상황은 크게 다음의 3가지 측면에서 변화하였다: (1)의료정책 발의(health care policy initiatives), (2)지불 체계 개혁과 가치(payment reform and value), (3)의료 전달 체계의 혁신과 변화(health care delivery system innovation and transformation).

- 첫째, 의료정책 발의에서 가장 중요한 변화는 오바마케어이다. 오바마케어는 의료 서비스의 가치와 효율성을 개선하여 의료 서비스의 가치와 효율성을 개선하고, 예방 전략을 구현하며, 인구집단 건강에 초점을 맞추고 있다. 그러나 이러한 발의 그 자체만으로는 환자와 인구집단 건강에 영향을 미치기에는 충분하지 않았다.

- 둘째, 지불체계 개혁과 가치 측면에서의 변화는, 행위별수가제(fee-for-service)에서 성과보상지불제(Pay for performance, PAP)와 가치기반성과보상지불제도(Valuebased purchasing, VBP), 그리고 포괄지불제(bundled payment)로 변화된 것이다. PAP와 VBP는 보건의료의 질 혹은 효율성에 대한 성과 기대치에 들어맞는 공급자(의사, 병원)에 보상함으로써 질 향상을 촉진하는 지불제도이다(신현웅 외, 2014: 18-19). 포괄지불제는 몇 가지 행위를 묶어서 보상하는 서비스 묶음제(bundle of services)로 미국의 메디케어가 대표적이다(박은철 외, 2014: 18-19).

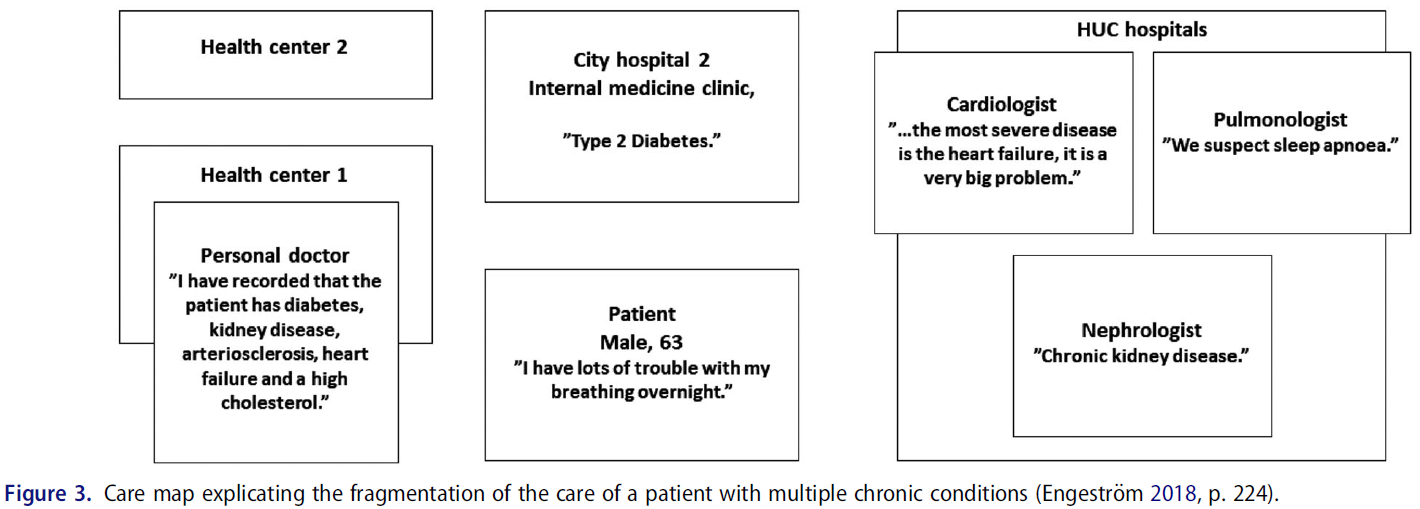

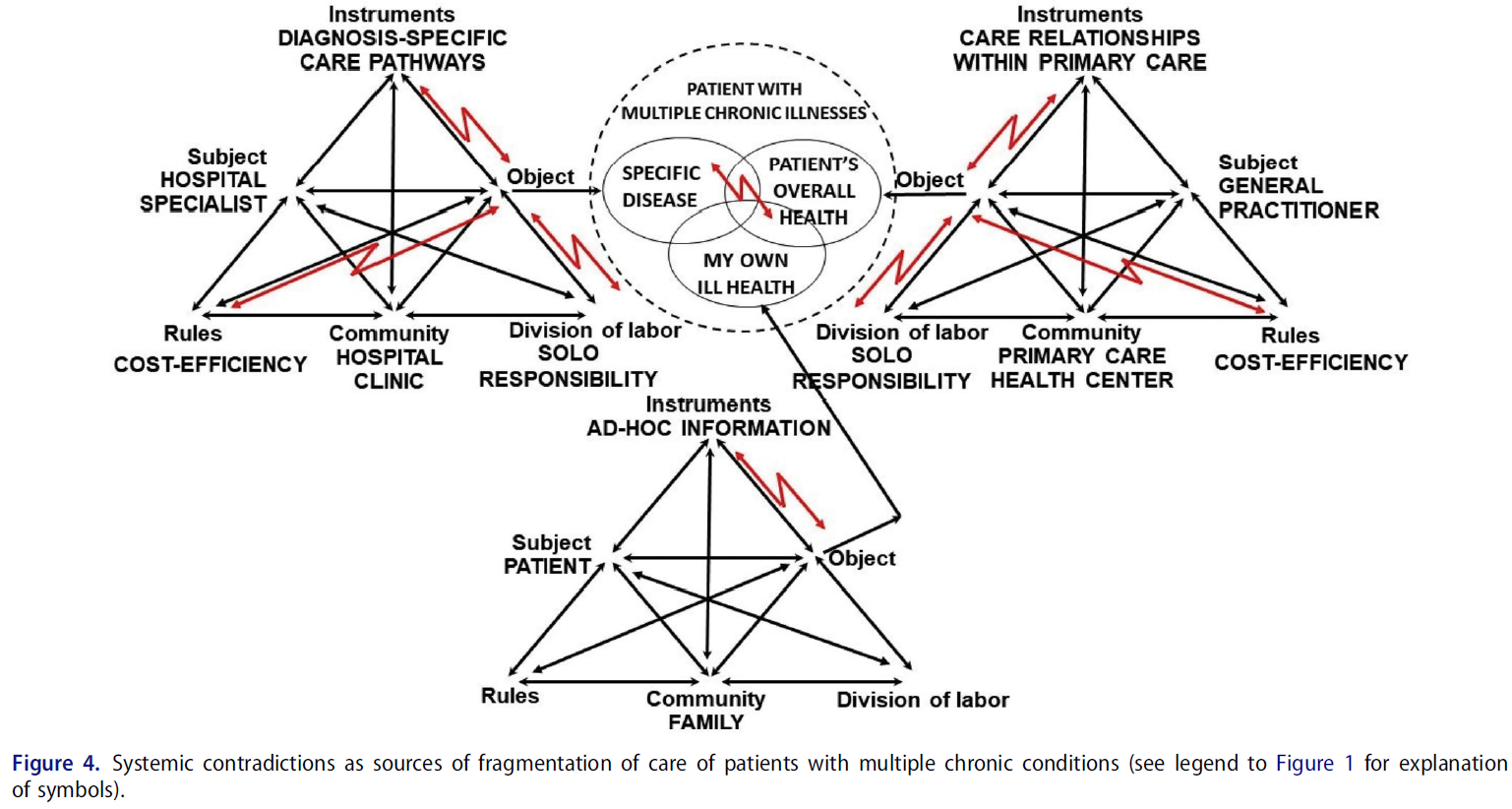

- 셋째, 의료 전달 체계의 혁신과 변화의 필요성은 기존의 의료 전달 체계가 높은 의료비용과 비효율성, 용납할 수 없는 수준의 환자 안전사고 및 의료 사고, 그리고 무엇보다도 취약 계층 환자들(행동 및 정신 건강 문제가 있는 환자, 소수 인종과 민족, 시골 거주민이거나 사회경제적으로 열악한 계층)의 필요성을 채워주지 못함에서 도출되었다. 이를 극복하기 위해서는 팀 기반 돌봄 모델, 전문직 간 협력, 돌봄 커뮤니티 형성이 필요하다는 지적이다(Skochelak et al., 2021: 2-4).

이상과 같이 오바마 케어 이후 변화된 의료비 지불 시스템의 개혁과 의료 전달 체계의 변화는 의료 환경의 변화를 촉구하였다. 의료계에서는 ‘3가지 목표(triple aim),’ 즉 “환자들의 진료 경험과 인구 집단의 건강을 향상시키면서 비용을 절감하는 것(improving patient experience and population health, and reducing cost)”을 그 목표로 삼고 있었다(Institute for Healthcare Improvement, 2009; Gonzalo et al, 2016: 35; Gonzalo et al, 2017: 123). 이러한 목표를 달성하기 위해서는 시스템 기반의 의료 환경15)에 노출될 필요가 있었고, HSS등장에도 영향을 미쳤다.

===

15) HSS에서 지적하는 시스템 기반의 의료 환경이란, 일개의 의료는 전체 시스템과 연결되어 있음을 의미한다. 즉 자신의 임상 전문 분야와 관련된 다양한 의료 서비스 제공 환경을 전체 시스템과의 관계 속에서 인식하는 것이 시스템 기반의 의료 환경이다. 이를 위해서 먼저 환자 치료 시 비용 절감에 대한 인식과 위험 편익 분석(risk benefit analysis)을 고려해야 한다. 아울러 양질의 환자 치료와 최적의 환자 치료 시스템을 인식해야 한다. 또한, 환자 안전을 강화하고 환자 치료의 질을 개선하기 위해 전문직 간 협력하여 팀에서 일해야 한다. 이를 통해서 궁극적으로 시스템 오류를 식별하고 잠재적인 시스템 솔루션을 구현해야 하는 것이 필요하다(NEJM Knowledge+ Team, Exploring the ACGME Core Competencies: Systems-Based Practice, 2016).

===

4. 의학 교육 개혁

1910년에서 1960년대까지 이상적인 의사의 모델은 모든 것을 독단적으로 처리할 줄 아는 ‘주도적인 의사(sovereign physician)’였다. 이 시기 동안 의사는 자율적이고 독립적이며 권위적이었고, 모든 의료 행위에 대해서 개인적으로 책임을 져야 했다. 이러한 모델은 주로 전염병 같은 급성질환이 많았던 20세기 중반까지는 매우 유용한 모델이었다. 특히 주치의를 제외한 대다수 대중은 의료정보에 접근할 수 없었고 피라미드형 의료 전달 체계에서 의사는 최고 위치에 있었다. 그러나 20세기 중반 이후 만성 질병이 주를 이루고 질병이 더욱 복합해지면서 의사 혼자가 아닌 협진 및 협력이 필요한 팀으로 의료 체계가 돌아가게 되었다. 환자들 역시 더 많은 의료 정보에 노출되기 시작하면서 이러한 ‘주도적인 의사’ 모델은 더는 유용하지 않게 되었다(Lucey, 2013: 1639-1640). 이러한 의료 체계와 의료과정의 변화는 앞으로 살펴볼 의학 교육에서도 변화를 요구하였고, 20세기 후반에는 새로운 의료와 의사 상이 등장할 필요가 있었다.

1) 1910년부터 1960년대까지의 변화

한편 의학교육에서도 1910년대를 거치면서 큰 변화를 맞이하였다. 현재와 같이 기초의학과 임상의학의 두 개의 기둥을 중심으로 하는 틀을 마련한 것은 1910년 에이브러햄 플렉스너(Abraham Flexner)가 존스 홉킨스 의과대학(Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine) 모델을 의학교육의 표본으로 제시하기 시작하면서부터였다. 155개 미국과 캐나다의 의과대학을 대상으로 조사한 후 작성된 플렉스너 보고서(Flexner Report)가 발간된 후 교육병원의 설립과 인턴십과 레지던트 트레이닝을 확립하는 등 의학교육의 질적 향상을 위한 노력, 즉 동일한 입학규정, 교과 과정 및 졸업 필수조건, 주에 의해 규제되는 면허제도 등을 시행하게 되었다(Flexner, 2005). 1937년에 이르면 92%의 의과대학 입학생들은 최소 3년 이상의 학사 과정을 공부한 후에 의과대학에 입학했고, 반 이상이 학부 학위를 가지고 입학하게 되었다(Bonner, 1995: 328-329). 플렉스너 보고서 이후 전반적으로 의과대학생들의 학력 수준의 상승과 의과대학 교육의 질적 · 양적 향상을 불러왔다.

플렉스너 리포트 출간 이후 1910년대에는 기본의학교육의 개혁에 관심을 두었다면, 제1차 세계대전과 제2차 세계대전 사이에는 압도적인 교육 시간을 보충하기 위해서 졸업 후 교육, 즉 인턴십과 레지던트 과정을 체계화시켰다. 제1차 세계대전 이후 1920년대를 거치면서 1-3년의 인턴십 프로그램과 존스 홉킨스 대학의 레지던트 프로그램이 전국적으로 도입되어 시행되었다(Ludmerer, 2023: 104-113). 이러한 수련은 교육병원을 통해서 이루어졌다. 이 시기부터 의과대학과 부속병원(university-owned or controlled hospital) 혹은 협력병원(affiliated hospital)은 ‘학술적 의학센터(academic medical centers)’로 불리게 되었다. 학술적 의학센터는 막대한 규모의 무료 진료를 제공했고, 국가 의료 시스템의 관점에서 보면 담당하는 자선 진료의 양이 엄청났다. 예를 들어 존스홉킨스 대학병원의 경우, 도시 빈민 외래 환자 진료의 거의 50%를 부담하고 있었다. 이 시기 동안 역사적으로 의학과 의사에 대한 신뢰도가 가장 높았던 시기로 기록되고 있다(Ludmerer, 2023: 129-133; 143; 147-8; 151).

제2차 세계대전은 의학 교육에 큰 변화를 초래하지 못했다. 그러나 의학교육을 받고 졸업한 의사들이 활동할 미국은 전혀 다른 사회로 변화하고 있었다. 뉴딜과 전쟁을 겪으면서 연방과 주 정부의 역할과 재정의 규모가 확대되었고, 의료에 대한 수요는 점점 더 늘어났다. 더불어 의료 서비스에 대한 권리는 모든 시민의 기본권으로 여겨졌다. 특히 제2차 세계대전 동안 연방정부와 미국 의과대학과의 관계에 큰 변화가 생겼다. 즉 연방정부의 막대한 지출을 통해 일반 교육 및 고등 교육뿐만 아니라 의학 교육 역시 성장시켰다. 일부 대학은 연구대학(research university)으로 지정되었고, 재정지원을 받아 국가적 목적을 달성하기 위한 주요한 기관으로 성장하였다. 이와 더불어 국립보건원(National Institute of Health)이 설립되었고, 1950년대를 겪으면서 미국 의학 연구는 양적 · 질적으로 황금기를 맞이하였다. 이 시기 동안 미국의 거의 모든 의과대학은 정부 지원금을 받아 의학과 과학 시설 확충도 더불어 일어났다(Ludmerer, 2023: 171-180).

1950년대 이후 베이비붐 세대(baby boomers)의 등장과 함께 역사상 최대 부를 누렸던 미국 사회에서 의료에 대한 수요는 기하급수적으로 늘어났다. 의료 역시 민권의 기본권이라는 개념이 자리 잡기 시작했다. 전쟁 이후시기에 부속 병원들은 지속해서 많은 수의 가난한 환자들을 담당하고 있었으나, 이러한 무료 환자의 비율은 점차 감소하였다. 대신 유료 환자의 수가 증가하면서 전일제 의과대학 교수진은 진료에 더 많이 관여하게 되었다. 아울러 그에 따른 병원의 수입도 많이 증가했다. 한편으로 치솟는 병원 이용비용으로 무료 환자 수의 감소와 함께 병상에 입원하는 환자 수가 감소하게 되면서, 임상 실습의 대상이 줄어들게 되었다. 이것은 의학교육에 지대한 영향을 미치는 것이었다. 즉 시간을 가지고 질병의 변화를 지켜보고 진단하면서 치료할 수 있었던 병상 환자 수의 감소는 교육적으로 큰 손실이었다(Ludmerer, 2023: 193-199).

이상과 같이 1910년대 이후 ‘임상-기초’의 두 쌍두마차를 기본 틀로 하는 의학교육 체제가 형성되었다. 의학 교육은 제2차 세계대전 이전부터 전문화와 표준화, 체계화 과정을 거쳤다. 의학교육은 제2차 세계대전의 영향으로 큰 변화를 맞이하지는 못했지만, 새롭게 변화된 사회에 걸맞은 의학교육의 필요성은 증가하였다.

2) 1960년대 이후부터 HSS 등장까지의 변화

1960-70년대에 현재의 미국 의학교육 체제가 확정되었다. 즉 4년의 의과대학 교육과 인턴십과 전공의 시험을 치르기 전의 레지던트 수련과정이 보다 체계화되었다. 1965년 이후 메디케어와 메디케이드 법안이 통과된 이후 의료 수요가 늘어나면서 의과대학 교수진들은 더 많은 시간을 임상에 매달렸다. 수백만의 미국인들이 민간 의료 시스템에 편입되면서 의료서비스의 이용이 급증하였고, 의료 기관들은 메디케어를 통해서 막대한 이윤을 벌어들였다. 1970-80년 통계에 의하면 대학의 부속병원에서 얻는 진료 수입이 의과대학 수입의 큰 부분을 차지하게 되었다. 대표적으로 존스 홉킨스 대학의 예를 들어보자면, 1970-71년에 임상 진료에 의한 수입은 1,901,000달러, 1974-5년에는 그 3배가 넘는 6,130,000 달러가 되었다. 10년 후인 1983-34년에는 10배 가까이 되는 6천만 달러에 육박했다(Ludmerer, 2023: 257-260).

1980년대에는 병원의 목표가 환자의 신속한 처리가 되었다. 앞서 언급한 대로 1983년 연방정부가 메디케어 환자들에 대한 병원비의 선불상환제도를 제정하는 법안을 통과시키면서 환자의 진단에 따라 증례당 정해진 비용을 지급하는 포괄수가제가 도입되었다. 이러한 변화는 경쟁적인 시장을 더욱 강화시켰다. 1980년대와 1990년대 HMO와 PPO(Preferred Provider Organization)로 대표되는 관리의료는 의사와 병원에 강력한 통제를 하였다. 관리의료기구로 인해 의학교육과 학술적 의학센터는 부정적인 영향을 받았다. 관리의료기구로 인해 전문화된 의료 서비스에서 일반 의료 서비스로 중심이 이동하였고, 이에 일차 의료에 지원하는 의대생의 수가 증가하였다. 그러나 가격 및 의료의 양도 동시에 제한하는 관리의료 체제에서는 학술적 의학센터는 재정적으로 어려움을 겪게 되었다. 무엇보다 환자들의 병원 체류 기간의 단축과 외래의 증가로 인해 병동의 학습 환경이 침식을 받았다. 결과적으로 의과대학과 학술적 의학센터는 관리의료 체제에 대처하기 위해 자본주의 경영방식을 도입하게 되었다. 궁극적으로는 학술적 의학센터는 사명과 존재 이유를 상실하게 되었다(Ludmerer, 2023: 388-396; 402-403).

관리의료 체제에서 환자와 의사의 면담 시간은 점차 줄어들면서 과소진료의 폐해가 나타났을 뿐만 아니라 의과대학의 책무, 즉 국민의 건강을 책임진다는 책임의식 역시 줄어들었다. 1990년대 들어서 학술적 의학센터는 국가가 필요로 하는 유형의 의사를 배출할 필요성에 따라 비용에 대한 인식, 예방의학, 건강진단, 환자 관리의 심리 사회적 차원 등의 교육을 개선할 필요가 있었다(Ludmerer, 2023: 422-423).

한편 1990년대부터 지속적인 환자 안전 문제와 낮은 효율성, 높은 비용 등 때문에 미국의 의료체제는 불안정한 모습을 보였다. ‘졸업 후 의학교육위원회(COGME)’를 비롯해서 많은 관련 기관에서는 지속 가능한 미국 의료 체제의 회복을 위해서 전문의 교육의 지식과 술기 면에서의 획기적인 개혁을 꾀하였다. ‘졸업 후 의학교육인증위원회(ACGME)’와 각 주의 면허허가기관, 전공의 보드(American Board of Medical Specialities)에서는 1998년부터 이를 개선하기 위한 노력을 시작하였다. 1999년에는 ‘ACGME 성과프로젝트(ACGME Outcome Project)’를 내놓았다. 여기서는 다음과 같은 여섯 개의 성과를 나열하였다: 환자돌봄(patient care), 의학지식(medical knowledge), 실습 중심의 교육과 향상(practice-based learning and improvement), 프로페셔널리즘(professionalism), 대인관계와 의사소통 기술(interpersonal skills and communication), 시스템 중심의 의료(system-based practice, SBP). ‘시스템 중심의 의료’란 일개의 의료는 더 큰 의료시스템과 연결되어 있다는 것을 인식하는 것이다. 예를 들자면, 2002년 미국의 의료체계 내에서 170만의 ‘병원 내 감염(nosocomial infection)’으로 인해 99,000명이 사망했다. 그 주된 이유는 만성적인 시스템 실패와 환자 안전의 문제를 등한시한 것 때문이었다.16)

===

16) 4년의 의과대학 전 대학교육, 4년의 의과대학 교육, 1년의 인턴십과 2-7년의 레지던트 교육과정을 통해서 의사들은 사례 중심의 의사결정과정(case-based decision tree), 즉 “만약-그렇다면(if-then)”의 논리적인 체계적인 의사결정 과정을 거쳐야 한다. 레지던트 프로그램에서는 보드 자격시험을 통과하는 것이 제일 중요한 목표이다. 그러므로 컴퓨터로 치르는 레지던트 보드 시험에서는 레지던트 프로그램의 개선을 위해 제시한 ‘ACGME 성과프로젝트(ACGME Outcome Project)’에서 제시한 6개의 성과 중 ‘의학지식’ 외에는 다른 5개의 성과는 13년이 지난 2013년에도 무용지물이었다. 이런 상황을 극복하기 위해서, 피터 N. 화이트헤드(Peter N. Whitehead)와 윌리엄 T. 쉐어러(William T. Scherer)는 6개의 교육성과 교과 과정은 레지던트 프로그램에서는 2년 차에, 그리고 그 아래 교육 단계인 의과대학 전 교육과 의과대학 교육프로그램에서도 포함해야 한다고 주장하였다(Whitehead & Scherer, 2013: 321-322).

===

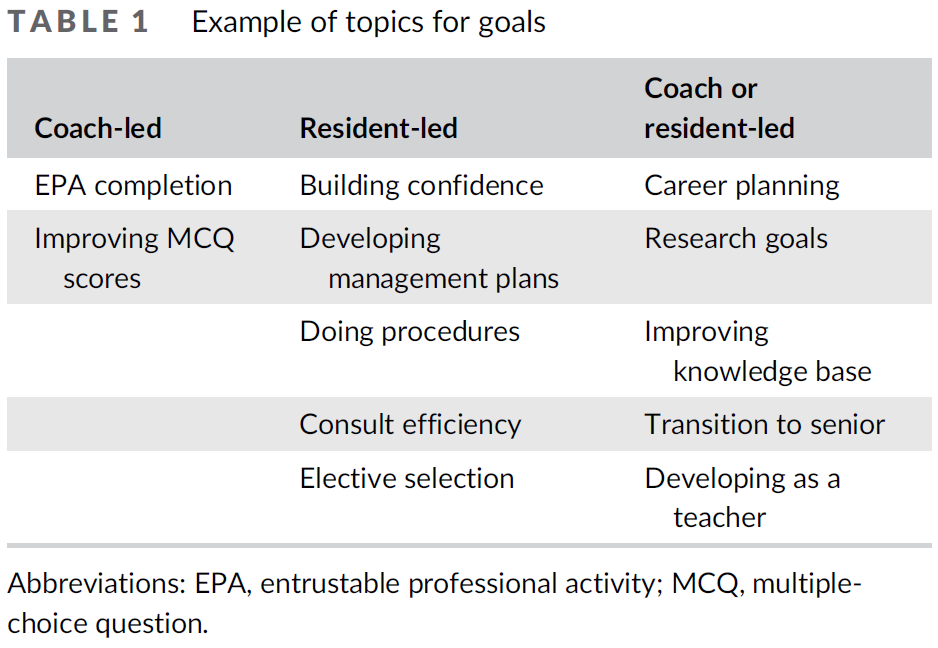

2000년부터 환자 안전, 가치 기반 헬스케어 등의 HSS의 기본적인 틀이 구체적으로 제시되었다. 2000년부터 2010년까지 미국과 캐나다의 의학교육계에서 출판된 15개의 보고서를 분석해 보면 다음과 같은 8가지 주제에 관심을 두고 의학교육을 개혁하고자 하였다. 즉

- 의학교육 연속성 통합,

- 평가와 의학 연구의 필요성,

- 재정확충을 위한 새로운 방법 모색,

- 리더십 교육의 중요성,

- 사회적 책무성에 대한 강조,

- 의학교육과 의료에서 새로운 기술의 활용,

- 의료 전달 체제의 변화와의 조응,

- 의료현장에서의 미래 방향성 등이다(Skochelak, 2010).

보고서마다 상이한 특징이 있지만, 그중에서 HSS의 내용과 비슷하거나 그 시초를 보이는 지적들이 있었다. 이 중 가장 큰 특징으로는 리더십, 사회적 책무성, 인구 집단 건강의 중요성, 새로운 기술을 이용한 교육, 그리고 보건 전달 시스템의 변화에 조응하는 교육, 非(비) 병원환경에서의 의학교육, 전문직종간 팀 훈련, 행동과학과 사회과학을 강조하는 교육, 만성 질병 관리, 질 향상, 환자 안전과 관련된 교육을 강조하였다는 점이다(Skochelak, 2010: S230-S232).

2007년부터는 변화하는 의료 체계에 발맞추고자 하는 HSS의 강조점과 더욱 흡사한 지적이 등장하기 시작했다.

- 『의학교육을 변화시킬 발의(Initiative to Transform Medical Education: Recommendations for Change in the System of Medical Education)』 (American Medical Association, 2007)에서는 지속해서 새로운 의료 시스템에서 핵심 역량을 발전시킬 것을 강조하였다.

- 『확장 시기의 의학교육 사명 재검토하기(Revisiting the Medical School Educational Mission at a Time of Expansion)』 (Hager & Russell, 2009)에는 사회적 요구(needs)와 기대에 부응하고자 하는 노력과 전문직종간 교육, 지역사회기반의 교육을 초기부터 시도하려는 노력이 필요하다고 주장하였다. 또한 변화를 위한 강한 학교 차원에서의 리더십, 대중의 건강관리 필요에 부응하는 의과대학의 사명체제, 전문직업성의 향상, 전문직종간 교육 기회, 교과 과정에서의 혁신, 의학교육과 건강관리에서의 새로운 기술 도입 등을 주장하고 있다.

- 『의료 전문직에서의 보수교육 재설계하기(Redesigning Continuing Education in Health Professions)』 (2009)에서는 지금까지 보수교육에서의 단점을 지적하면서 국가 차원의 전문직종간 평생 교육 기관을 세워서 팀 기반(team-based)의 교육 환경을 조성하자는 의견을 제시하였다.

- 『누가 일차 의료를 제공하고 어떻게 그들을 훈련할 것인가(Who Will Provide Primary Care and How Will They Be Trained)』 (Culliton & Russell, 2010)에서는 미국에서의 일차 의료 서비스의 부족에 대해 지적을 하면서 일차 의료는 새롭게 변화하는 의료체계 시스템으로 통합되어야 한다고 지적하고 있다.

- 『의사 교육하기(Educating Physicians: A Call for Reform of Medical School and Residency)』 (Cook, Irby & O’Brian, 2010)에서는 표준화된 교육체계와 다른 의료 종사자들과의 팀 기반 교육체계, 공식적이고 경험적인 교육의 지속성의 필요성 등을 지적하였다.

앞서 언급된 의학 교육의 변화 요구는 2010년 오바마케어 이후 변화된 의료 체제의 변화에 부합하기 위해 HSS로 구체화되어 제시된 것으로 보인다. 이상과 같이 1960년대 이후 공적 의료 보험의 확대, 관리의료와 관리경쟁, 오바마 케어까지 미국의 의학 개혁 노력은 의학교육에도 변화를 초래하였다. 이러한 변화는 의사를 비롯한 의료인의 역할 역시 새로운 변화를 요구하였다. 의료인은 단순히 기초 및 임상 과학을 익히는 것을 넘어서서 사회적, 환경적, 경제적, 기술적 시스템의 복잡·다양함을 이해하고 이를 전문직업성(professionalism)의 영역까지 확대하는 역할을 담당해야 한다는 인식이 강해졌다. 또한, 1960년대 이후 진행된 일련의 의료체계의 변화는 의과대학과 병원에서의 변화를 요구하였다. 즉 2010년대에 AMA를 중심으로 제시된 HSS는 미국 의료 체제와 미국 의학교육의 당면한 과제를 해결하기 위한 대안으로 출발하였다.

5. 결론

이 연구에서는 HSS의 등장 배경을 의료 체계 개혁과 의학교육을 중심으로 살펴보았다. 의학교육에서의 HSS 도입과 적용에 관한 연구는 미국에서 증가하고 있으나, 의료 체계의 변화와 의학교육을 연결해 그 역사적 등장 배경을 고찰한 논문은 아직은 없었다. HSS는 미국에서 기초의학과 임상의학 외의 나머지 부문을 포괄하면서 등장한 분야이다. 이것은 7개의 ‘핵심역량,’ 4개의 ‘기반역량,’ 이들을 모두 아우르는 ‘시스템 사고’로 구성되어 있다. 이것은 기본적으로 포괄적인 팀 기반 의사전문직업성 정체성 형성을 위한 교육 모델이다. 2013년 AMA가 제시한 HSS를 많은 의과대학에서 교과 과정에 도입하고 있다. HSS의 콘텐츠를담은 교과 과정을 가르치는 학교들은 전체 일반의과대학과 정골의학대학 전체의 70%를 넘고 있다.

2010년대 HSS의 등장과 유행에는 미국의 의료제공 체제의 큰 변화와 관련이 있었다. 역사적으로 미국의 의료제도는 환자-의사의 양자 관계를 기반으로 한사적 영역으로 규정되어 왔다. 이러한 의료체계에 대응하여 20세기 초부터 전국건강보험제도 도입을 위한 노력들이 있었다. 그러나 2번의 세계대전과 대공황, 매카시즘을 겪으면서 이 논의는 1960년대까지 별 진전이 없었다. 1960년대 중반 의료보장 프로그램인 메디케어와 메디케이드가 신설되면서 국가적 차원의 의료지원 시스템이 일부 미국인들을 위해 운영되었다. 1970년대에는 HMO가 제정되면서 관리의료체제가 자리를 잡아갔다. 1970-80년대를 동안 조용하면서도 꾸준히 논의되어온 의료체제 개선안은 1990년대 클린턴 행정부에서 「건강보장법」을 통해서 열매를 거두는 것처럼 보였으나 결국 실패하고 말았다. 드디어 오바마 행정부에서 ‘오바마케어’로 알려진 의료보험개혁법을 통과시킴으로써—비록 아직까지도 불완전하고 문제점을 안고 있었지만—전국민건강보험체제를 이룩하였다.

1910년부터 1960년대까지 미국 의학 교육의 역사는 표준화(standardization)와 전문화(professionalization) 과정이라고 할 수 있었다. 식민지 시기부터 1910년 의학교육의 패러다임을 변화시킨 플렉스너 보고서가 나오기까지, 의학교육의 역사는 지속적인 의료체계 변화의 필요성과 현실적 이해관계와 한계 속에서 조금씩 변화해 온 것이라 할 수 있었다. 플렉스너 보고서 이후 100여 년간 미국 의학 교육은 ‘기초 의학과 임상 의학이라는 두 기둥’을 중심으로 형성되었다. 의료체계 변화의 역사적 사건들이 쌓이게 되면서 2010년대 HSS의 기본적인 개념과 교육 시스템이 구축되는 결과를 낳게 되었다. HSS는 ‘제3의 의학’이라는 이름으로 2010년 오바마케어의 등장과 함께 의학교육의 한 축을 담당하게 되었다.

이 글을 마치면서 분명히 해야 할 것은 앞서 살펴본 바와 같이 HSS는 미국적인 상황에서 등장한 미국 의학교육의 새로운 흐름이라는 점이다. 미국은 OECD 국가 중 가장 높은 의료비를 지출하는 나라지만, 낮은 의료 혜택때문에 기대수명이 2022년 기준 남성(73)과 여성(79) 모두 OECD 평균인 80.5세에 미치지 못하고 있다(강진욱, 2022). 이는 건강 형평성(equity)을 이루지 못하고 있는 미국의 의료보험 체제의 문제에서 찾을 수 있다. 미국은 오바마 케어가 등장하기 이전에 OECD 주요국 중 전국민건강보험 제도를 도입하지 않은 유일한 나라였다. 이는 미국 의료의 역사에서 의사 중심의 의료가 환자와 국민 중심의 의료로 변화하기 위한 지속적인 노력과 제도의 변화가 있었지만, 아직도 의료보험 체제의 미흡함을 여전히 가지고 있음을 나타낸다. 또한, 전문가들은 미국 보건체제가 불공정하고 비효율적임을 지적하고 있다. 코로나 19를 겪으면서 모든 사회 구성원에게 고른 의료 혜택을 베풀어야 한다는 의식이 팽배해졌다. 2016년 통계에 의하면 현재 미국은 다른 선진국에 비해 질병 부담이 31%나 더 높고, ‘예방 가능한 질병(preventable disease)’으로 인한 병원 입원의 수가 더 많았다(Singh, Gullett, & Thomas, 2021: 1282). 코로나 19 팬데믹은 미국 보건 및 의료 시스템의 열악한 측면을 극명하게 보여주었다. 특히 흑인을 비롯한 非(비) 백인들의 낮은 코로나 19 검사율과 높은 발병률을 보여주며, 높은 사망률로 이어졌다. 이러한 미국 의료의 불공정성과 비효율성은 역사적으로 본문에서 언급한 몇 가지 사건들을 계기로 조금씩 진보되는 모습을 보이기는 하였으나 아직도 개선의 여지가 많음을 보여준다.

이러한 미국의 의료 공급과 의료체제 측면에서 볼 때 HSS는 미국적인 의학체제에 대응하기 위한 의학교육의 문제를 해결하기 위해 등장했음을 알 수 있다. 최근 일부 학계에서는 HSS를 한국 의학교육에 도입하고자 하는 노력을 하고 있다. HSS가 추구하는 교육 목표는 의료계의 팀 기반 의료체계와 환자 안전에 대한 관심의 증가와 함께, 다인종 · 다문화 사회, 그리고 저출산과 초고령화를 향해 가는 한국 사회에서도 시사하는 바가 없다고는 할 수 없다. 그러나 HSS가 추구하고 달성하고자 하는 교육 목표와 지향점을 역사적으로 고찰해 볼 때, 무분별한 선망이나 모방은 한국 의학교육이나 한국 사회의 당면 문제를 해결하지 못하는 것은 물론이고 혼란만 초래할 것으로 보인다. 그러므로 미국 사회와 의료 체제에 맞게 설계된 HSS는 깊은 숙고 후에 한국적인 상황과 의학교육에 맞는 일부만 선별적으로 조심스럽게 도입하는 것이 바람직하다.

Notes

Korean J Med Hist 2023; 32(2): 623-659.

Published online: August 31, 2023

의료시스템과학 등장의 역사적 배경: 1910년대부터 2010년대까지의 미국 의료 체계 개혁과 의학교육을 중심으로

*건양대학교 의과대학 의료인문학교실, 의료인문학특임조교수

The Historical Context of the Emergence of Health Systems Science (HSS): Changes in the U.S. Healthcare System and Medical Education from the 1910s to the 2010s

*Assistant Research Professor, Department of Medical Humanities, Konyang University College of Medicine

© 대한의사학회

Abstract

색인어: 의료시스템과학, 의학교육, 의료개혁, 오바마케어, 의료보험

Keywords: Health Systems Science, medical education, medical reform, ObamaCare, health insurance

'Articles (Medical Education) > 인문사회의학(의사학, 의철학 등)' 카테고리의 다른 글

| 새로운 의료인문학(들)과 한국 의료인문학의 자리* (Philosophy of Medicine 2023) (0) | 2024.01.26 |

|---|---|

| 의학교육에서 의료인문학의 가치: 의사학을 중심으로 (Korean J Med Hist, 2022) (1) | 2023.11.16 |

| 부정의 바로잡기: 어떻게 여자 의과대학생이 주체성을 발휘하는가 (Adv Health Sci Educ Theory Pract. 2023) (0) | 2023.09.14 |

| 갭에 마음쓰기: 성찰의 여러 이점에 관한 철학적 분석(Teach Learn Med, 2023) (0) | 2023.08.26 |

| 반대편-질환에-존재함: 의학교육과 임상진료의 현상학적 존재론(Teach Learn Med, 2023) (0) | 2023.08.25 |