학습 대 수행: 통합적 문헌고찰 (Perspectives on Psychological Science, 2015)

Learning Versus Performance: An Integrative Review

Nicholas C. Soderstrom and Robert A. Bjork

강의실에서든 현장에서든 교육의 주요 목표는 학습자에게 내구성과 유연성을 모두 갖춘 지식 또는 기술을 갖추게 하는 것입니다. 우리는 지식과 기술이 사용하지 않는 기간 동안에도 계속 사용할 수 있고, 단순히 교육 중에 경험하는 것과 일치하는 컨텍스트에서뿐만 아니라 관련성이 있는 다양한 컨텍스트에서 접근할 수 있다는 점에서 유연하기를 원합니다. 즉, 교육은 [학습]을 촉진하기 위해 노력해야 하며, 이는 [장기적인 유지와 전이를 지원하는 행동이나 지식의 비교적 영구적인 변화]를 의미한다. 그러나 역설적으로 이러한 학습은 획득 과정 중 또는 직후에 관찰되고 측정될 수 있는 행동 또는 지식의 일시적인 변동을 의미하는 [수행]와 구별되어야 한다.

Whether in the classroom or on the field, the major goal of instruction is, or at least should be, to equip learners with knowledge or skills that are both durable and flexible. We want knowledge and skills to be durable in the sense of remaining accessible across periods of disuse and to be flexible in the sense of being accessible in the various contexts in which they are relevant, not simply in contexts that match those experienced during instruction. In other words, instruction should endeavor to facilitate learning, which refers to the relatively permanent changes in behavior or knowledge that support long-term retention and transfer. Paradoxically, however, such learning needs to be distinguished from performance, which refers to the temporary fluctuations in behavior or knowledge that can be observed and measured during or immediately after the acquisition process.

학습과 수행의 구별은 중요한데, 이는 현재 상당한 학습이 수행이 향상되지 않은 상태에서 발생할 수 있고, 반대로 수행의 상당한 변화가 종종 해당 학습의 변화로 변환되지 않는다는 것을 보여주는 압도적 경험적 증거가 존재하기 때문이다. 아마도 훨씬 더 설득력 있는, 특정 실험 조작은 학습과 성과에 반대 효과를 주는 것으로 보여져, 획득 중에 가장 많은 오류를 생성하는 조건이 종종 가장 많은 학습을 생성하는 바로 그 조건이다. 그러한 결과는 사람들이 자신의 학습에 대해 판단을 내리도록 요구받거나 연구원, 교육자, 학생들과의 비공식 대화 중에 정기적으로 불신에 직면한다. 그러나 실제와 이론적 관점 모두에서 흥미롭고 중요한 것은 학습과 수행의 구별에 대한 [반직관적인 특성]입니다.

The distinction between learning and performance is crucial because there now exists overwhelming empirical evidence showing that considerable learning can occur in the absence of any performance gains and, conversely, that substantial changes in performance often fail to translate into corresponding changes in learning. Perhaps even more compelling, certain experimental manipulations have been shown to confer opposite effects on learning and performance, such that the conditions that produce the most errors during acquisition are often the very conditions that produce the most learning. Such results are regularly met with incredulity, whether in the context of metacognitive research in which people are asked to make judgments about their own learning or during informal conversations with researchers, educators, and students. It is, however, the counterintuitive nature of the learning–performance distinction that makes it so interesting and important from both practical and theoretical perspectives.

우리는 [장기 보존 또는 이전으로 측정되는 학습]과 [획득 중 측정되는 성과] 사이의 중요한 차이와 관련된 증거에 대한 첫 번째 통합 검토를 제공한다. 우리는 메타인지 관련 작업과 함께 운동 및 언어 학습 영역의 연구를 통합하려고 시도한다. 그러나 다른 많은 기사에서 학습과 성능의 차이를 소개하고 그 차이를 설명하는 주요 결과를 요약하고 있습니다. 또한, 우리(Soderstrom & Bjork, 2013)는 매년 갱신될 예정인 주석 첨부 참고 문헌 목록을 발행하여 연구자, 교육자 및 기타 연구자들이 주제와 관련된 최신 연구에 보조를 맞출 수 있도록 하고 있습니다.

We provide the first integrative review of the evidence that bears on the critical distinction between learning, as measured by long-term retention or transfer, and performance, as measured during acquisition. We attempt to synthesize research from both the motor- and verbal-learning domains, as well as relevant work in metacognition. We note, however, that a number of other articles provide an introduction to the learning versus performance distinction and summarize key findings that illustrate the distinction (e.g., R. A. Bjork, 1999; Christina & Bjork, 1991; Jacoby, Bjork, & Kelley, 1994; Kantak & Winstein, 2012; Lee, 2012; Lee & Genovese, 1988; Schmidt & Bjork, 1992; Schmidt & Lee, 2011; Wulf & Shea, 2002). As well, we (Soderstrom & Bjork, 2013) have published an annotated bibliography that is slated to be updated annually so as to keep researchers, educators, and others abreast of the newest research relevant to the topic.

기초 연구

Foundational Studies

수십 년 전에 수행된 연구는 [수행에 변화가 없으면서도 상당한 학습이 발생할 수 있다는 것]을 보여줌으로써 학습과 성과 사이의 구별을 필요로 했다. 예를 들어, 쥐의 미로 학습은 그들의 행동이 목적이 없는 것처럼 보이는 자유 탐험 기간을 허용함으로써 향상될 수 있다(즉, 성과가 불규칙하다). 수행이 점근선("오버러닝")에 도달한 후 제공되는 추가 연습 시험 결과 망각 속도가 느려지고 재학습 속도가 빨라졌다. 그리고 피로가 앞으로 해야 할 운동 작업의 수행을 방해할 때, 학습은 여전히 진행될 수 있습니다. 이 섹션에서는 이러한 기초 연구를 검토합니다.

Studies conducted decades ago necessitated the distinction between learning and performance by showing that considerable learning could occur in the absence of changes in performance. For example, rats’ learning of a maze could be enhanced by permitting a period of free exploration in which their behavior seemed aimless (i.e., performance was irregular); additional practice trials provided after performance was at asymptote (“overlearning”) resulted in slowed forgetting and more rapid relearning; and when fatigue stalled performance of to-be-learned motor tasks, learning could still transpire. This section reviews these foundational studies.

잠복 학습

Latent learning

[잠복 학습]은 [명백한 강화나 눈에 띄는 행동 변화 없이 발생하는 학습]으로 정의된다. 학습은 '잠재적' 또는 '숨김'이라고 하는데, 그 이유는 그것을 드러내기 위해 어떤 종류의 강화가 도입되지 않는 한 전시되지 않기 때문이다. 예를 들어, 최근 새로운 도시로 이사한 사람이 운전에 대해 우려하여 매일 시내버스를 타고 출근한다고 가정해 보자. 매일 버스를 타고 다니면서, 그 경로는 관찰을 통해 학습될 것이지만, 그러한 학습은 그러한 동기가 필요한 경우에만(예를 들어, 그 사람이 스스로 운전해서 일할 필요가 있을 때) 명확해질 것이다. 잠복 학습의 초기 발견은 흥미롭고 논란이 많았는데, 이는 학습이 강화가 있을 때만 일어날 수 있다는 널리 알려진 가정에 도전했기 때문이다. 초기 잠복학습 연구의 고전적인 리뷰를 위해, 우리는 "인지적 지도cognitive map"의 개념이 도입된 톨만(1948년)을 추천한다. 이 용어는 [자신의 공간 환경의 정신적 표현]을 가리킨다.

Latent learning is defined as learning that occurs in the absence of any obvious reinforcement or noticeable behavioral changes. Learning is said to be “latent,” or hidden, because it is not exhibited unless a reinforcement of some kind is introduced to reveal it. Consider, for example, a person who recently moved to a new city and, apprehensive about driving, decides to ride the city bus each day to work. Riding the bus day after day, the route would be learned through observation, but such learning would only be evident if an incentive was present that required it—say, when it was necessary for the person to drive to work on his or her own. The early findings of latent learning were intriguing and controversial because they challenged the widely held assumption that learning could occur only in the presence of reinforcement. For a classic review of the early latent learning studies, we recommend Tolman (1948), in which the concept of “cognitive maps” was introduced, a term that refers to the mental representation of one’s spatial environment.

Blodgett(1929년), Tolman(1930년)과 Honzik(1930년)에 의해 처음 입증되었지만, 그 결과는 학습과 기억력에 관한 대부분의 교과서에 보고되어 있는 잠복 학습에 대한 고전적인 실험으로 여겨지고 있다. 본질적으로 Blodgett의 복제인 그들의 실험에서, 세 그룹의 쥐들은 총 17일 동안 매일 복잡한 T-maze에 놓였습니다. 한 그룹의 쥐는 골 박스에 도달하기 위해 강화되지 않았습니다.골 박스에 도달할 때마다 다른 그룹은 음식으로 강화되었습니다. 세 번째 그룹은 11일째까지 골대에 도달한 것에 대해 보상을 받지 못했으며, 그 후 정기적으로 보상을 받았다. 이 실험의 결과는 그림 1과 같다. 당연하게도 17일 동안 골박스 찾기에서 오류가 가장 적은 그룹은 정규 강화 그룹이었고, 강화되지 않은 그룹은 오류가 가장 많았다. 잠재 학습의 개념과 일관되게, 지연 강화 그룹은 즉각적인 개선이 발생한 11일째(식품이 도입된 날)까지 단 한 번도 강화하지 않은 그룹과 동일한 오류 수를 보였으며, 오류율은 정규 강화 그룹과 비슷한 수준으로 떨어졌다. 따라서, 보강을 늦추는 것은 쥐들이 실제로 보강이 이루어지지 않은 상태에서 미로를 배운다는 것을 드러냈고 그들의 행동은 오히려 목적 없는 것처럼 보였다. 수행은 정체된 상태로 학습이 이뤄졌다는 얘기다.

Although first demonstrated by Blodgett (1929), Tolman and Honzik (1930) are credited for providing what is now considered the classic experiment on latent learning, the results of which are reported in most textbooks on learning and memory. In their experiment, which is essentially a replication of Blodgett’s, three groups of rats were placed in a complex T-maze every day for a total of 17 days. One group of rats was never reinforced for reaching the goal box—they were simply taken out of the maze when they found it—whereas another group was reinforced with food every time the goal box was reached. A third group was not rewarded for reaching the goal box until Day 11, after which time they were regularly rewarded. The results of this experiment are presented in Figure 1. Unsurprisingly, the group that made the fewest errors in finding the goal box over the 17-day period was the regularly reinforced group, and the group that was never reinforced made the most errors. Consistent with the notion of latent learning, the delayed-reinforcement group showed the same number of errors as the never-reinforced group until Day 11—the day the food was introduced—when an immediate improvement occurred, dropping their error rate to a level comparable to that of the regularly reinforced group. Thus, delaying reinforcement revealed that the rats did, indeed, learn the maze while no reinforcement was provided and their behavior seemed rather aimless. In other words, learning occurred when performance was stagnant.

Blodgett(1929)와 Tolman and Honzik(1930)의 연구는 쥐의 잠복학습에 대한 수많은 후속 실험을 촉진하여 이 현상에 대한 우리의 이해를 더욱 향상시켰다. 예를 들어, Seward(1949)는 잠복학습이 30분간의 자유탐험 후에 일어날 수 있으며, 나아가 강화 없이 미로에서 보내는 시간(따라서 성능의 변화가 식별되지 않는 시간)이 미로 학습과 긍정적인 관련이 있음을 보여주었다(Bendig, 1952; 레이놀즈, 1945 참조).

The studies by Blodgett (1929) and Tolman and Honzik (1930) spurred numerous follow-up experiments on latent learning in rats, further refining our understanding of this phenomenon (see Buxton, 1940; Spence & Lippitt, 1946). Seward (1949), for example, showed that latent learning could occur after just 30 min of free exploration and, furthermore, that the amount of time spent in the maze with no reinforcement—and thus during a time when no changes in performance were discernible—was positively related to learning the maze (see also Bendig, 1952; Reynolds, 1945).

잠복학습이 쥐에게만 국한된 것이 아니라는 것도 수십 년 전에 분명해졌다. 그들의 영향력 있는 연구에서, Postman and Tuma(1954)와 Stevenson(1954)은 잠복 학습이 인간에서도 경험적으로 입증될 수 있다는 것을 보여주었다. Stevenson의 실험에서, 3살 정도의 어린 아이들은 상자를 열 수 있는 열쇠를 찾기 위해 일련의 물체를 탐험했습니다. 중요한 것은 탐색된 환경에는 키 이외의 오브젝트 또는 태스크와 무관한 오브젝트도 포함되어 있다는 것입니다. 문제는 핵심 관련 물체를 탐색하는 동안 아이들이 이러한 주변 물체의 위치를 학습할 것인지 여부였다. 즉, 아이들이 잠재 학습을 보일 것인지 여부였다. 실제로 아이들에게 중요하지 않은 물건을 찾으라고 했을 때, 아이들은 그 물건들이 탐색된 환경에 있을 때 상대적으로 더 빨리 찾을 수 있었습니다. 스티븐슨은 또한 아이들에게서 관찰된 잠복 학습의 양이 나이가 들수록 증가한다는 것을 발견했다.

It was also made clear decades ago that latent learning is not limited to rats. In their influential studies, Postman and Tuma (1954) and Stevenson (1954) showed that latent learning is also empirically demonstrable in humans. In Stevenson’s experiment, children—some as young as 3 years old—explored a series of objects to find a key that would open a box. Critically, the explored environment also contained nonkey objects, or those that were irrelevant to the task. The question was whether the children would learn the locations of these peripheral objects during the exploration of the key-relevant objects—that is, whether the children would show latent learning. Indeed, when the children were asked to find the irrelevant, nonkey objects, they were relatively faster in doing so when those objects had been contained in the explored environment. Stevenson also found that the amount of latent learning observed in the children increased with age.

과잉학습과 피로

Overlearning and fatigue

이미 연주할 수 있음에도 불구하고 계속 연습하는 바이올리니스트, 즉 획득한 퍼포먼스가 이미 점근점에 도달한 바이올리니스트를 생각해 보십시오. 작업에 대한 숙달 기준이 달성된 후에도 작업에 대한 이러한 지속적인 연습은 "[오버러닝]"이라고 하며, 포스트마스터리 시행 횟수를 숙달에 필요한 시행 횟수로 나눈 것으로 나타낼 수 있습니다. 예를 들어 바이올리니스트가 한 곡을 마스터하기 위해 10번의 연습시험이 필요한 후에 추가로 5번 연습했다면, 오버러닝의 정도는 50%가 될 것이다. 난센스 음절을 사용한 에빙하우스(1885/1964)의 유명한 연구로 시작된 과잉학습의 많은 초기 연구는 정보와 기술의 장기적 학습을 향상시키는 방법으로서 과잉학습의 힘을 증명했다. Fitts(1965)는 이러한 발견을 언급하며, "일부... 기준에 도달한 시점을 넘어서까지의 지속적인 연습의 중요성은 아무리 강조해도 지나치지 않다"고 말했다(p.195).

Consider a violinist who continues to practice a musical piece despite already being able to perform it—that is, after acquisition performance is already at asymptote. Such continued practice on a task after some criterion of mastery on that task has been achieved is referred to as “overlearning” and can be expressed by the number of postmastery trials divided by the number of trials needed to reach mastery. For example, if the violinist practiced a piece 5 additional times after needing 10 practice trials to master it, then the degree of overlearning would be 50%. Many early studies of overlearning—starting with Ebbinghaus’s (1885/1964) famous study using nonsense syllables—demonstrated the power of overlearning as a method for enhancing the long-term learning of information and skills. Referencing these findings, Fitts (1965) stated, “The importance of continuing practice beyond the point in time where some . . . criterion is reached cannot be overemphasized” (p. 195).

크루거(1929)는 오버러닝에 대해 가장 많이 인용된 연구를 수행했다. 그의 중요한 실험에서, 두 그룹의 참가자들은 모든 단어를 기억할 수 있을 때까지 반복적으로 단어 목록을 연구했다. 이 시점에서, 대조군은 연구 단계를 끝낸 반면, 오버러닝 그룹의 참가자들은 자료를 계속 연구했습니다. 사실, 그들은 자료를 100% 더 많이 학습했습니다. 즉, 대조군보다 두 배 더 많은 연구 실험에 노출되었습니다. 최대 28일 후에 수행된 보존 테스트에서, 오버러닝 그룹의 참가자들은 연구 단계에서 자료를 습득했지만 오버러닝하지 않은 대조 그룹의 참가자보다 더 많은 항목을 리콜했습니다. 또한 과잉학습의 정도에 따라 보유율이 증가하였다. 후속 연구에 따르면, 오버러닝(과잉학습)은 산문 구절과 같은 보다 복잡한 구두 자료를 유지하는 데 도움이 되며, 재학습relearning 속도, 즉 다소 지연된 후 해당 자료를 다시 학습하는 데 필요한 시간을 단축하는 것으로 나타났습니다.

Krueger (1929) carried out the most frequently cited study on overlearning. In his seminal experiment, two groups of participants repeatedly studied lists of words until all of the words could be recalled. At that point, the control group was finished with the study phase, whereas participants in the overlearning group continued studying the material—in fact, they overlearned the material by 100%, meaning that they were exposed to twice as many study trials as the control group. On a retention test administered up to 28 days later, the participants in the overlearning group recalled more items than participants in the control group, who had mastered the material during the study phase but had not overlearned it. Additionally, retention increased as a function of the degree of overlearning. Subsequent research showed that overlearning aids in the retention of more complex verbal materials, such as prose passages, and accelerates the rate of relearning—that is, the amount of time required to learn the material again after some delay (e.g., Gilbert, 1957; Postman, 1962; see also Ebbinghaus, 1885/1964).

오버러닝(과잉학습)은 또한 운동 기술을 배우는 데 도움이 된다. 크루거(1929)가 단어에 대한 과도한 학습을 보여준 다음 해, 그는(크루거, 1930) 미로 추적 작업에 대해 비슷한 이점을 보였다. 참가자들은 처음에 100% 정확도에 도달할 때까지 과제를 수행했고, 그 후 50%, 100% 또는 200% 더 많이 학습했습니다. 언어 자료와 마찬가지로, 과잉 학습의 양은 장기 보존과 긍정적으로 관련되었습니다. 이후 작업은 M60 기관총의 조립 및 분해(Schendel & Hagman, 1982)를 포함하여 단순하고 복잡한 운동 기술에 대한 오버러닝의 이점을 재현했다(예: Chasey & Knowles, 1973; Melnick, 1971; Melnick, Lersten, Lockhart, 1972). 오버러닝은 다양한 업무에 효과적인 학습 도구인 것 같습니다.

Overlearning also benefits the learning of motor skills. The year after Krueger (1929) demonstrated overlearning for words, he (Krueger, 1930) showed similar benefits for a maze-tracing task. Participants first performed the task until they reached 100% accuracy, after which they overlearned it by 50%, 100%, or 200%. As with the verbal materials, the amount of overlearning was positively related to long-term retention. Later work replicated the benefits of overlearning for simple and more complex motor skills (e.g., Chasey & Knowles, 1973; Melnick, 1971; Melnick, Lersten, & Lockhart, 1972), including the assembly and disassembly of an M60 machine gun (Schendel & Hagman, 1982). Overlearning seems to be an effective learning tool for a wide range of tasks (for a meta-analytic review, see Driskell, Willis, & Cooper, 1992).

과잉학습에 대한 연구와 유사하게, 피로에 대한 초기 연구는 피로가 획득 중에 성능의 추가적인 향상을 방해한 후에도 학습이 발생할 수 있음을 시사했다. 예를 들어 애덤스와 레이놀즈(1954년)는 공군 기초 훈련병들에게 회전바퀴에 달린 목표물을 지팡이로 수동으로 추적해야 하는 회전 추격 임무를 배우게 했다. 시험 사이의 휴식 간격을 바꾸면 피로가 성능 향상을 제한하거나 제거했을 때, 피로가 사라진 후 과제에 대한 후속 테스트에서 드러났듯이 그럼에도 불구하고 학습이 발생하는 것으로 나타났다. 15년 후, Stelmach(1969)는 다양한 훈련 일정이 사다리 오르기 과제의 학습과 수행에 어떻게 영향을 미치는지 조사했다. 한 그룹의 참가자들은 그들이 쉬었던 것보다 더 많이 연습했고, 다른 그룹은 그들이 연습한 것보다 더 많이 쉬었습니다. 훈련 중 성과는 주어진 시험에서 상승한 단의 수로 정의되며, 더 많은 보간 휴식이 허용된 그룹에 유리했다. 다른 그룹은 시험 사이에 휴식을 거의 받지 못했기 때문에 훈련 중에 점점 더 피곤해진다는 것을 고려하면 이 결과는 놀라운 일이 아니다. 그러나 지연된 후, 유지 테스트에서 휴식을 거의 받지 못한 그룹이 잘 쉬었던 그룹을 따라잡은 것으로 밝혀졌는데, 표면적으로는 피로가 단기 성과에서 이득을 억제했을 때, 상당한 학습이 일어났다는 것을 증명했다.

Similar to research on overlearning, early work on fatigue suggested that learning could occur even after fatigue prevented any further gains in performance during acquisition. Adams and Reynolds (1954), for example, had basic trainees from the Air Force learn a rotary pursuit task, which requires one to manually track a target on a revolving wheel with a wand. Varying the length of rest intervals between trials showed that when fatigue limited or eliminated gains in performance, learning nonetheless occurred, as revealed by a subsequent test on the task after the fatigue had dissipated. Fifteen years later, Stelmach (1969) examined how different training schedules affect learning and performance on a ladder-climbing task. One group of participants practiced more than they rested; another group rested more than they practiced. Performance during training, which was defined as the number of rungs climbed on a given trial, favored the group that was permitted more interpolated rest. This finding is not surprising given that the other group, as a result of receiving little rest between trials, became increasingly fatigued during the training. After a delay, however, a retention test revealed that the group that received little rest caught up to the well-rested group, ostensibly demonstrating that substantial learning had occurred when fatigue had stifled any gains in short-term performance.

대응하는 개념상의 차이

Corresponding conceptual distinctions

잠재 학습, 과잉 학습, 피로 및 기타 고려사항에 대한 초기 실험은 훈련 또는 획득 중 관찰할 수 있는 행동(즉, 성과)을 구별하기 위해 초기 학습 이론가(예: Estes, 1955a; Guthrie, 1952; Hull, 1943; Skinner, 1938; Tolman, 1932)를 주도했고 상대적으로 영구적인 변화를 가져왔다. 향후 그러한 행동을 나타낼 수 있는 능력(즉, 학습)에서 발생한다.

- 헐은 반응의 습관 강도와 반응의 순간적인 반응 잠재력이라는 용어를 사용했고,

- 에스테스는 그의 변동 모델에서 습관 강도와 반응 강도를 언급했고,

- 스키너는 반사 예비력과 반사 강도를 구별했다.

경험적으로, 습관 강도 또는 반사 예비력(즉, 학습)은 소멸 또는 망각에 대한 저항성 또는 재학습 속도에 의해 지수화되는 것으로 가정한 반면, 순간 반응 잠재력, 반응 강도 또는 반사 강도(즉, 성과)는 반응의 현재 확률, 속도 또는 대기 시간에 의해 지수화되는 것으로 가정했다.

The early experiments on latent learning, overlearning, and fatigue, plus other considerations, led early learning theorists (e.g., Estes, 1955a; Guthrie, 1952; Hull, 1943; Skinner, 1938; Tolman, 1932) to distinguish between behaviors that can be observed during training, or acquisition (i.e., performance), and the relatively permanent changes that occur in the capability for exhibiting those behaviors in the future (i.e., learning).

> Hull used the terms habit strength of a response and the momentary reaction potential of that response;

> Estes, in his fluctuation model, referred to habit strength and response strength; and

> Skinner differentiated between reflex reserve and reflex strength.

Empirically, habit strength, or reflex reserve (i.e., learning), was assumed to be indexed by resistance to extinction or forgetting, or by the rapidity of relearning, whereas momentary reaction potential, response strength, or reflex strength (i.e., performance) was assumed to be indexed by the current probability, rate, or latency of a response.

인간의 언어 학습 분야에서, Tulving과 Pearlstone의 구분(1966)은 각각 "이용 가능성"(즉, 메모리에 저장된 것)과 "접근가능성"(즉, 주어진 시간에 검색 가능한 것)을 학습과 성과에 완벽하게 매핑한다. 마지막으로, R. A. Bjork와 Bjork(1992)는 인간의 언어 및 운동 학습에 대한 연구의 광범위한 발견을 설명하기 위해 학습과 수행의 구별이 각각 저장 강도와 검색 강도에 의해 색인화되는 새로운 학습 이론을 공식화했다. 이 설명과 학습-성과 구별에 관한 다른 현대의 이론적 관점은 나중에 논의한다.

In the domain of human verbal learning, Tulving and Pearlstone’s (1966) distinction between “availability” (i.e., what is stored in memory) and “accessibility” (i.e., what is retrievable at any given time) also maps, albeit not perfectly, onto learning and performance, respectively. Finally, R. A. Bjork and Bjork (1992), in an effort to account for a wide range of findings in research on human verbal and motor learning, formulated a new theory of learning in which the distinction between learning and performance is indexed by storage strength and retrieval strength, respectively. This account, as well as other contemporary theoretical perspectives regarding the learning–performance distinction, is discussed later.

요약

Summary

학습 대 수행의 차이는 잠재 학습, 과잉 학습 및 피로를 연구한 연구자들이 [실제로 학습이 이루어지고 있다는 징후가 없는 상태에서도 훈련 또는 수행의 습득 중에 장기간 학습이 발생할 수 있다는 것을 증명]한 수십 년 전으로 거슬러 올라갈 수 있다. 특히 잠복학습의 결과는 당시 설득력 있고 논란이 많았는데, 이는 학습을 드러내기 위해서는 강화가 필요하지만 학습을 유도할 필요는 없다는 것을 입증했기 때문이다. 요약하자면, 이 초기 작업은 [수행 없는 학습]을 보여주었다. 다음 몇 절에서는 그 반대가 사실임을 보여주는 보다 최근의 증거를 검토한다. 특히, 성능의 향상은 더 많은 성능 오류를 유발하는 조건에 비해 종종 사후 훈련 학습을 방해한다.

The learning versus performance distinction can be traced back decades when researchers of latent learning, overlearning, and fatigue demonstrated that long-lasting learning could occur while training or acquisition performance provided no indication that learning was actually taking place. The results of latent learning studies, in particular, were both compelling and controversial at the time because they verified that, although reinforcement is necessary to reveal learning, it is not required to induce learning. In sum, this early work showed learning without performance. In the next several sections, we review more recent evidence showing that the converse is also true—specifically, that gains in performance often impede posttraining learning compared with those conditions that induce more performance errors.

프랙티스의 분산

Distribution of Practice

학습과 수행의 상관관계는 학습해야 할 기술이나 정보의 학습일정을 조작함으로써 반복적으로 발견되어 왔다. 연습 또는 스터디 세션을 몰아치기(즉, 같은 것을 반복해서 연습하거나 공부하는 것)하는 것은 일반적으로 단기 성과에 도움이 되는 반면, 연습 또는 스터디 세션을 시간 또는 다른 활동과 분리하는 것은 일반적으로 장기적인 학습을 촉진합니다. 이 절에서는 실습의 분포가 학습과 성과에 다른 영향을 미치는 것으로 나타난 운동 및 구두 학습 영역의 실험을 차례로 제시한다.

The dissociation between learning and performance has been repeatedly found by manipulating the study schedules of to-be-learned skills or information. Massing practice or study sessions—that is, practicing or studying the same thing over and over again—usually benefits short-term performance, whereas distributing practice or study—that is, separating practice or study sessions with time or other activities—usually facilitates long-term learning. This section presents, in turn, experiments from the motor- and verbal-learning domains in which the distribution of practice was shown to have differential influences on learning and performance.

운동 학습

Motor learning

수영하는 사람이 앞, 뒤, 접영을 개선하려고 한다고 가정합니다. 수영 선수의 훈련이 하루에 1시간으로 제한된다고 가정해 보자. 한 가지 훈련 옵션은 다른 스트로크를 20분씩 연습한 후 다음 훈련 세션에서 이전에 연습한 스트로크로 돌아가지 않고 매스(또는 차단)하는 것입니다. 또는 각 스트로크가 다음 스트로크로 넘어가기 전에 10분 동안 연습하도록 연습 일정을 분배(또는 무작위화)할 수 있습니다. 이 일정에 따라 훈련 세션 동안 각 스트로크를 한 번 더 재방문할 수 있습니다. 이 섹션에서는 매스 연습이 훈련 중 빠른 성과 향상을 촉진할 수 있지만, 연습을 분산하면 해당 기술을 장기간 유지할 수 있음을 시사하는 연구를 검토한다.

Suppose a swimmer wishes to improve his or her front, back, and butterfly strokes. Suppose further that the swimmer’s training is restricted to 1 hr per day. One training option would be to mass (or block) the different strokes by practicing each for 20 min before moving on to the next, never returning to the previously practiced strokes during that training session. Alternatively, he or she might distribute (or randomize) the practice schedule such that each stroke is practiced for 10 min before moving on to the next stroke. This schedule would permit each stroke to be revisited one more time during the training session. In this section, we review research that suggests that, whereas massing practice might promote rapid performance gains during training, distributing practice facilitates long-term retention of that skill.

배들리와 롱맨(1978년)과 J.B. Shea와 Morgan(1979)은 연습을 분배하는 것이 단순한 운동 기술의 학습과 수행에 차별적인 영향을 미친다는 것을 보여주는 두 가지 고전 연구를 발표했다. 영국 우체국의 의뢰를 받아, Baddelley와 Longman은 새로 도입된 우편 번호를 키보드에 입력하는 우체국 직원들의 능력을 최적화하는 방법을 조사했다. 문제는 우체국 직원들이 하루 몇 시간씩 연습하면서 가능한 한 빨리 새로운 시스템을 배워야 하는지, 아니면 연습이 더 많이 보급되면 학습이 가장 이득이 될 것인가 하는 것이었다. 매일 연습량과 연습이 발생한 일수를 변화시키면서, 더 분산된 연습은 타자기의 키 입력의 보다 효과적인 학습을 촉진했다. 그러나, 기준에 도달하는 일수 대 시간 수로 측정되는 기술 습득의 효율성에 관해서는 그 반대였다.기준에 도달하기 위해서: 즉, 분산 그룹은 매스 그룹에 대해 특정 수준의 퍼포먼스에 도달하기 위해 더 많은 일수가 필요했습니다. 요약하면, 몰아치기massed 연습은 키 입력의 신속한 습득을 지원했지만, 분산 연습은 기술의 장기 보유를 향상시켰다(Simon & Bjork, 2001 참조).

Baddeley and Longman (1978) and J. B. Shea and Morgan (1979) published two classic studies that showed that distributing practice has differential effects on learning and performance of a simple motor skill. Commissioned by the British Postal Service, Baddeley and Longman investigated how to optimize postal workers’ ability to type newly introduced postcodes on the keyboard. The question was whether the postal workers should learn the new system as rapidly as possible, practicing several hours per day, or whether learning would profit most if practice was more distributed. Varying the amount of practice per day and the number of days in which practice occurred, more distributed practice fostered more effective learning of the typewriter keystrokes; however, the opposite was true in regard to the efficiency in which the skill was acquired, as measured by the number of days to reach criterion versus the number of hours to reach criterion—that is, the distributed group required more days to reach any given level of performance relative to the massed group. In sum, massed practice supported quicker acquisition of the keystrokes, but distributed practice led to better long-term retention of the skill (see also Simon & Bjork, 2001).

J. B. Shea와 Morgan(1979)은 또한 운동 기술을 장기간 유지하는 데 도움이 된다는 것을 보여주었다. 그들의 중요한 실험에서, 참가자들은 세 가지 다른 움직임 패턴을 배웠는데, 각각의 움직임에는 정해진 순서에 따라 세 개의 작은 나무 장벽(6개 중 한 개)을 넘어뜨리는 것이 포함되었습니다. 두 가지 다른 연습 일정, 즉 차단과 랜덤이 구현되었습니다. 블록 프랙티스 조건에서는 3가지 동작 패턴 각각이 18회 연속적으로 연습된 반면 랜덤 프랙티스 조건에서는 참가자의 입장에서 예측할 수 없는 방식으로 각 패턴의 18회 동작이 다른 패턴에 대한 시험 사이에 혼재되었다. 따라서 중요한 것은 세 가지 작업에 대한 연습 시간이 두 가지 다른 연습 조건에 걸쳐 동일하다는 것이다. 관심사는 서로 다른 연습 일정이 팔 움직임이 실행되는 속도에 어떻게 영향을 주느냐였다.

J. B. Shea and Morgan (1979) also showed that distributing practice benefits the long-term retention of a motor skill. In their seminal experiment, participants learned three different movement patterns, each of which involved knocking over three (of six) small wooden barriers in a prescribed order. Two different practice schedules were implemented: blocked and random. In the blocked-practice condition, each of the three movement patterns was practiced for 18 trials in succession, whereas in the random-practice condition, the 18 trials of each pattern were intermingled among the trials on the other patterns in a way that was unpredictable from a participant’s standpoint. Importantly, therefore, practice time for the three tasks was equated across the two different practice conditions. Of interest was how the different practice schedules affected the rapidity in which the arm movements were executed.

J.B.의 결과. Shea와 Morgan(1979)은 그림 2에 나와 있다. 첫째, 획득 중에 팔 움직임을 수행하는 데 필요한 짧은 시간에서 알 수 있듯이, 차단된 연습 조건에 할당된 참가자가 무작위 연습 조건의 참가자들보다 더 나은 성과를 보였다. 하지만 각 그룹이 습득한 기술을 얼마나 잘 유지할 수 있을까요? 10분 및 10일 후에 실시되는 유지 테스트에서는 참가자는 블록(B) 또는 랜덤(R) 방식으로 각 스킬에 대해 테스트를 실시하여 참가자의 4개의 서브그룹(B-B, B-R, R-B 및 R-R)을 생성했습니다. 쌍의 첫 번째 문자는 획득 중에 실습이 어떻게 스케줄 되었는지를 나타내며, 두 번째 문자는 각 그룹이 어떻게 테스트되었는지를 나타낸다. 그림 2에서 볼 수 있듯이, 인수 시 차단된 관행의 이점은 지연 후 더 이상 명확하지 않습니다. 실제로 10분 및 10일 후에 학습이 평가될 때 패턴이 역전되었습니다. 즉, 전반적으로 무작위 순서로 기술을 처음 연습한 사람들이 가장 많은 학습을 보였습니다. 블록 방식으로 테스트된 그룹(B-B 대 R-B)을 비교한 결과, 이 연구는 획득 중 [무작위 실행]이 획득 중 [블록식 실행]보다 더 낫다는 것을 보여주었다. 이러한 패턴은 연구자들이 지연된 테스트에서 무작위 순서(B-R 대 R-R)로 테스트된 그룹을 비교했을 때 극적으로 입증되었다. 따라서 Baddeley와 Longman(1978년)과 마찬가지로, Shea와 Morgan은 여러 가지 학습된 이동 패턴의 블록식 관행이 획득 성과를 촉진하는 반면, 동일한 이동 패턴의 인터리빙 관행이 장기 보존을 촉진한다는 것을 보여주었다(이 발견의 복제 및 연장은 Lee & Magill, 1983 참조). 그림 2에는 나타나지 않았지만 Shea와 Morgan은 인터리빙의 전송 이점도 발견했기 때문에 처음에 랜덤 방식으로 스킬을 연습한 참가자들은 새로운 응답 패턴, 즉 연습하지 않은 응답 패턴을 비교적 잘 수행할 수 있었습니다.

The results of J. B. Shea and Morgan (1979) are shown in Figure 2. First, it is clear that during acquisition, participants assigned to the blocked-practice condition performed better than those in the random-practice condition, as evidenced by shorter times required to perform the arm movements. But how well would each group retain the acquired skills? On retention tests given after 10 min and 10 days, participants were tested on each skill in either a blocked (B) or random (R) fashion, which produced four subgroups of participants: B-B, B-R, R-B, and R-R. The first letter in the pair denotes how practice was scheduled during acquisition; likewise, the second letter denotes how each group was tested. As can be seen in Figure 2, the advantage of blocked practice during acquisition was no longer evident after a delay. In fact, the pattern reversed when learning was assessed after 10 min and 10 days—that is, overall, those who initially practiced the skills in a random order exhibited the most learning. Comparing the groups that were tested in a blocked fashion (B-B vs. R-B), the study showed that random practice during acquisition was better than blocked practice during acquisition. This pattern was dramatically demonstrated when researchers compared the groups that were tested in a random order (B-R vs. R-R) on the delayed test. Thus, similar to Baddeley and Longman (1978), Shea and Morgan showed that blocking practice of several to-be-learned movement patterns facilitated acquisition performance, whereas interleaving practice of those same movements promoted long-term retention (see Lee & Magill, 1983, for a replication and extension of these findings). Although not shown in Figure 2, Shea and Morgan also found a transfer advantage of interleaving, such that participants who initially practiced the skill in a random fashion were relatively better in executing a new response pattern—that is, one that had not been practiced.

J. B. Shea와 Morgan(1979)의 결과는 별도의 학습 과제를 인터리빙하면 장기적인 보존을 강화할 수 있다는 여러 후속 시연과 함께 Battig(1979)가 상황 간섭 효과로 언급한 광범위한 발견의 한 예로 작용한다. 주로 구두 쌍으로 구성된 학습 과제(Battig, 1962, 1972 참조)의 발견에 기초하여, Battig는 습득 중 별도의 학습 과제 간의 가능한 [간섭]을 증가시키는 조건은 습득 프로세스 중 장기 보존과 전이를 향상시킬 수 있다고 제안했다. 예를 들어 테니스에서 포핸드, 백핸드, 서브 스트로크와 같이 학습해야 할 개별 태스크에 무작위로 트라이얼을 혼합하면 스트로크의 구성 요소 간의 간섭이 증가하지만 이러한 기술의 장기 보유를 향상시킬 수 있습니다.

J. B. Shea and Morgan’s (1979) results, together with the multiple subsequent demonstrations that interleaving separate to-be-learned tasks can enhance long-term retention, serve as one example of a broader finding, referred to by Battig (1979) as contextual interference effects. Primarily on the basis of findings from verbal paired-associate learning tasks (see Battig, 1962, 1972), Battig proposed that conditions during acquisition that act to increase the possible interference between separate to-be-learned tasks can enhance long-term retention and transfer, despite their depressing effects on performance during the acquisition process. Randomly intermixing the trials on separate to-be-learned tasks, such as, say, the forehand, backhand, and serve strokes in tennis, increases the interference between the components of those strokes but then can enhance long-term retention of those skills.

J.B.의 결과. Shea와 Morgan(1979)은 많은 후속 연구를 촉진시켰으며, 그 중 다수는 현장 기반이었고 더 복잡한 운동 기술을 조사했다. 그러한 연구에서, 배드민턴 선수들은 차단되거나 무작위로 인터리빙된 연습 일정에 따라 코트 한쪽에서 세 가지 다른 종류의 서브를 배웠다. 유지 간격 후, 선수들은 서브가 연습된 코트의 같은 쪽과 반대쪽에서 서브 테스트를 받았다. 차단된 그룹은 훈련 중에 더 잘 수행했지만, 인터리브 그룹은 코트의 같은 면이든 반대 면이든 상관없이 더 나은 장기 보존을 보였다(S. Goode & Magill, 1986). 따라서 연습을 배포하면 연습한 특정 스킬의 보유가 강화될 뿐만 아니라 그 스킬의 보다 나은 이전(즉, 다른 컨텍스트에서의 스킬 적용)이 촉진됩니다. 분산 연습에 의해 촉진되는 학습 혜택은 또한 야구와 피아노 곡에서 다른 종류의 공을 치는 것을 배우는 것과 어린이와 나이 든 성인 모두에게 증명되었습니다. 단순하고 복잡한 운동 기술에 대한 분산 연습의 영향에 대 한 검토는 Lee(2012)와 Merbah and Meulemans(2011)를 추천한다.

The results of J. B. Shea and Morgan (1979) spurred many follow-up studies, many of which were field based and examined more complex motor skills. In one such study, badminton players learned three different types of serves from one side of the court under blocked or randomly interleaved practice schedules. After a retention interval, the players were tested on the serves from both the same and opposite side of the court from which the serves were practiced. The blocked group performed better during training, but the interleaved group showed better long-term retention, whether tested on the same or opposite side of the court (S. Goode & Magill, 1986). Thus, not only does distributing practice enhance the retention of the specific skill that is practiced, but it also fosters better transfer of that skill—that is, the application of the skill in a different context. The learning benefits promoted by distributed practice have also been demonstrated for learning to hit pitches of different types in baseball (Hall, Domingues, & Cavazos, 1994) and piano pieces (Abushanab & Bishara, 2013) and for both children (e.g., Ste-Marie, Clark, Findlay, & Latimer, 2004) and older adults (e.g., Lin, Wu, Udompholkul, & Knowlton, 2010). For reviews of the effects of distributed practice on motor skills, both simple and complex, we recommend Lee (2012) and Merbah and Meulemans (2011).

구두 학습

Verbal learning

운동 영역에서와 같이, 언어 과제의 경험적 증거는 학습 기회를 분산(또는 띄어쓰기)하는 것이 매스하는 것에 비해 학습에 도움이 된다는 것을 시사한다, 언어 문헌에서 발견한 것을 간격두기 효과라고 한다. 간격두기 효과를 최초로 입증한 에빙하우스(1885/1964)는 공간 연구 기회가 질량이 아닌 재료를 망각하기 더 쉽게 만든다는 것을 보여주었다. 수십 년 후, 이 주제에 관한 고전적인 기사가 발표되었습니다(예: Battig, 1966; Madigan, 1969; Melton, 1970). 예를 들어, 현재 검토와 특히 관련이 있으며, 피터슨, 윔플러, 커크패트릭, 솔츠만(1963)은 매스 항목이 종종 단기적으로 더 잘 유지되는 반면(즉, 간격두기가 수행을 손상시킴), 간격이 있는 항목은 장기간에 걸쳐 더 잘 유지된다는 것을 최초로 관찰했다(즉, 간격두기가 학습을 강화시킴). 그 이후 수백 개의 실험에서 간격 효과가 매우 견고하고 신뢰할 수 있음을 입증했다(검토는 Cepeda, Pashler, Vul, Wixted, 2006; Dempster, 1988 참조). 이제 간격 효과의 증거와 이 실험 조작이 학습-성과 구별에 어떤 영향을 미치는지 선택적으로 검토한다. 다음 두 가지 방법으로 간격이 확보되는 상황을 그룹화했습니다. (a) 필요한 정보 또는 절차의 반복 사이에 휴식 또는 관련 없는 활동 기간을 삽입한다. (b) 여러 가지 다른 (아마도 방해될 수 있는) 작업이나 구두 자료의 연구 또는 연습 시험을 인터리브함으로써. 그러나 현재 인터리빙의 이점이 이러한 인터리빙이 도입된 공간의 이점을 넘어서는가 하는 것이 현재 활성 문제이다(예: Birnbaum, Kornell, Bjork, 2013; Kang & Pashler, 2012 참조).

As in the motor domain, empirical evidence from verbal tasks suggests that distributing (or spacing) study opportunities benefits learning relative to massing them, a finding in the verbal literature termed the spacing effect. The first to demonstrate the spacing effect, Ebbinghaus (1885/1964) showed that spacing study opportunities, as opposed to massing them, rendered the material more resistant to forgetting. Decades later, now-classic articles were published on the topic (e.g., Battig, 1966; Madigan, 1969; Melton, 1970). For example, and particularly relevant to the current review, Peterson, Wampler, Kirkpatrick, and Saltzman (1963) were the first to observe that massed items are often retained better in the short term (i.e., spacing impairs performance), whereas spaced items are retained better over the long term (i.e., spacing enhances learning; see also Glenberg, 1977). Since then, hundreds of experiments have demonstrated the spacing effect to be highly robust and reliable (for reviews, see Cepeda, Pashler, Vul, Wixted, & Rohrer, 2006; Dempster, 1988). We now selectively review evidence of the spacing effect and how this experimental manipulation bears on the learning–performance distinction. We note that we have grouped together situations in which spacing is achieved in two different ways: (a) by inserting periods of rest or unrelated activity between repetitions of to-be-learned information or procedures; and (b) by interleaving the study or practice trials of several different—and possibly interfering—to-be-learned tasks or verbal materials. A currently active issue, however, is whether the benefits of interleaving go beyond the benefits of the spacing such interleaving introduces (see, e.g., Birnbaum, Kornell, Bjork, & Bjork, 2013; Kang & Pashler, 2012).

간격두기 효과를 검토하는 대부분의 연구는 단일 단어 또는 짝을 이룬 동료와 같은 비교적 단순한 학습 자료를 사용하여 수행했다. 예를 들어, 한 연구에서 고등학생들은 프랑스어-영어 단어 쌍(예: l'avocat-변호사)을 하루에 30분씩 연속적으로 학습하는 집단 연습 또는 3일마다 10분씩 학습하는 간격(분산) 연습 조건 하에서 배웠다. 각 연습 일정 직후에 투여된 초기 테스트(매스 그룹에 대한 30분 연구 세션 후와 간격 그룹에 대한 세 번째 10분 연구 세션 후)에서 실질적으로 동일한 단기 성과가 관찰되었다. 그러나 7일 후에 투여된 장기 보존 테스트에서, 연구 간격을 둔 참가자들은 연구를 집결한 참가자보다 더 많은 쌍을 회상했다(Bloom & Shuell, 1981년). 마찬가지로, 간격두기 학습 세션은 외국어 단어 쌍의 습득을 실제로 늦출 수 있지만, 몇 년의 기간 동안에도 여전히 우수한 유지로 이어질 수 있다(Bahrick, Bahrick, Bahrick, 1993).

The majority of studies examining the spacing effect have done so using relatively simple to-be-learned materials, such as single words or paired associates. In one study, for example, high school students learned French–English vocabulary pairs (e.g., l’avocat—lawyer) under conditions of either massed practiced, in which the pairs were studied for 30 consecutive minutes on one day, or spaced (distributed) practice, in which the pairs were studied for 10 min on each of three consecutive days. On an initial test that was administered immediately following each practice schedule—after the 30-min study session for the massed group and after the third 10-min study session for the spaced group—virtually identical short-term performance was observed. However, on a long-term retention test administered 7 days later, participants who had spaced their study recalled more pairs than participants who had massed their study (Bloom & Shuell, 1981). Similarly, spacing study sessions, relative to massing them, can actually slow down the acquisition of foreign language vocabulary pairs but can still lead to superior retention—even over a span of several years (Bahrick, Bahrick, Bahrick, & Bahrick, 1993).

간격두기 효과의 나이와 관련된 차이도 조사되었다. 예를 들어, 젊은 성인(18~25세)과 나이 든 성인(61~76세) 모두 미사일이 있거나 간격을 둔 프레젠테이션 일정에 따라 관련이 없는 짝을 이룬 동료(예: 키튼-다임)를 여러 번 연구했다. 연속 큐드-리콜 패러다임을 사용하여 각 항목은 항목의 마지막 프레젠테이션 이후에 2개(단기 보존) 또는 20개(장기 보존)의 개입 항목이 제시된 후 테스트되었다. 놀라운 사실은 나이 든 성인들이 젊은 성인에 비해 전반적으로 더 나쁜 성과를 보인다는 것이다. 보다 흥미롭고 학습-성과 구별과 관련이 있는 두 연령대는 간격별 상호 작용을 보였다. 즉, 단기 보존(즉, 성과)은 [대량 보존 항목]을 선호한 반면, 장기 보존(즉, 학습)은 [간격 있는 항목]을 선호했다. (바로타, 듀첵, 1989년)

Age-related differences in the spacing effect have also been examined. For example, both younger (ages 18–25) and older (ages 61–76) adults studied unrelated paired associates (e.g., kitten–dime) multiple times according to either a massed or spaced presentation schedule. Using a continuous cued-recall paradigm, each item was tested after either 2 (short retention) or 20 (long retention) intervening items were presented following the item’s last presentation. An unsurprising finding was that older adults performed worse, overall, compared with their younger counterparts. More interesting, and relevant to the learning–performance distinction, both age groups exhibited a spacing-by-retention-interval interaction—that is, short-term retention (i.e., performance) favored the massed items, whereas long-term retention (i.e., learning) favored the spaced items (Balota, Duchek, & Paullin, 1989).

간격은 단순한 자료의 보존성을 높일 뿐만 아니라 산문 구절(예: Rawson & Kintsch, 2005)과 논리(Carlson & Yaure, 1990)와 귀납적 추론과 같은 보다 복잡한 자료의 학습도 개선한다. 특히 눈에 띄는 예는 다양한 유형의 수학 문제를 묶는 것이 아니라 띄어쓰기가 학습을 용이하게 한다는 것을 보여주었다. 참가자들의 과제는 네 개의 다른 모양의 물체의 기하학적 부피를 찾는 방법을 배우는 것이었다. 한 그룹은 한 개체에 대해 4개의 문제를 시도한 후 다음 개체에 대해 4개의 문제로 넘어가는 등 정해진 일정에 따라 연습 문제를 풀었고, 다른 그룹은 무작위로 혼합된 순서로 다양한 모양의 문제를 풀었습니다. 참가자들은 일주일 후에 그 문제에 대해 테스트를 받았다. 연습 단계 동안 참가자들은 이러한 문제를 블록 방식으로, 즉 성능 향상을 대량으로 연습하면 더 많은 문제를 해결할 수 있었습니다. 그러나 장기 보존 테스트에서는 이 패턴이 반대로 나타났다.참가자는 이러한 문제를 1주일 전에 혼합 형식(즉, 공간 활용 학습 강화)으로 연습하면 문제를 해결할 수 있는 능력을 더 잘 유지할 수 있었다(Rohrer & Taylor, 2007). 이러한 결과는 학습과 성과 간의 차이를 예시한다(Rohrer, Dedrick, & Burgess, 2014; Taylor & Rohrer, 2010 참조).

In addition to fostering better retention of simple materials, spacing also improves the learning of more complex materials, such as prose passages (e.g., Rawson & Kintsch, 2005), and the learning of higher-level concepts, such as logic (Carlson & Yaure, 1990) and inductive reasoning (e.g., Kang & Pashler, 2012; Kornell & Bjork, 2008; Kornell, Castel, Eich, & Bjork, 2010). A particularly striking example showed that spacing various types of math problems, as opposed to massing them, facilitates learning. Participants’ task was to learn how to find the geometric volume of four differently shaped objects. One group worked through the practice problems according to a blocked schedule, such that four problems for one object were attempted before moving on to four problems for the next object, and so on; the other group worked through the problems for various shapes in a randomly mixed order. Participants were then tested on the problems 1 week later. During the practice phase, participants were able to solve more of the problems if those problems were practiced in a blocked fashion—that is, massing improved performance. This pattern reversed, however, on the long-term retention test: Participants better retained the ability to solve the problems if those problems were practiced 1 week earlier in a mixed format—that is, spacing enhanced learning (Rohrer & Taylor, 2007). These results exemplify the distinction between learning and performance (see also Rohrer, Dedrick, & Burgess, 2014; Taylor & Rohrer, 2010).

요약

Summary

운동 및 언어 학습 영역의 증거는 장기 학습이 학습해야 할 기술 또는 정보를 시간 또는 기타 개입 활동과 함께 분산(간격두기)함으로써 이익을 얻는다는 것을 보여준다. 그러나 단기적으로는 몰아치기massed 연습이 더 나은 경우가 많다. 따라서, 타이핑, 배드민턴, 외국어 말하기 또는 기하학 문제를 배우고 싶은 경우, 그러한 일정이 연습이나 습득 중에 더 많은 오류를 유발할 수 있더라도 분산 연습 일정을 시행하는 것을 고려해야 한다.

Evidence from the motor- and verbal-learning domains demonstrates that long-term learning profits from distributing (spacing) the practice of to-be-learned skills or information with time or other intervening activities. In the short term, however, massed practice is often better. Thus, whether one wishes to learn how to type, play badminton, speak a foreign language, or solve geometry problems, one should consider implementing a distributed practice schedule, even if such a schedule might induce more errors during practice or acquisition.

연습의 변화주기

Variability of Practice

예를 들어 목표 스킬과 관련이 있지만 다른 연습 스킬을 갖는 등 연습이나 학습 세션의 조건을 분산시키는 것은 습득 중 성과에 악영향을 미칠 수 있지만 장기적인 학습과 이전을 촉진할 수 있습니다. 이러한 맥락에서 대부분의 연구는 운동 학습에 초점을 맞췄지만, 언어 학습에 대한 소수의 연구들 또한 연습의 [가변성]의 장기적인 이점을 보여주었다. 우리는 이제 학습과 성과에 대한 연습의 가변성이 분리할 수 없는 영향을 보여준 운동과 언어 학습 전통 모두의 연구를 검토한다.

Similar to distributing practice, varying the conditions of practice or study sessions—for example, by having a trainee practice skills related to but different from the target skill—can also have detrimental effects on performance during acquisition but then foster long-term learning and transfer. Most of the research in this vein has focused on motor learning, although a handful of studies on verbal learning have also demonstrated the long-term benefits of practice variability. We now review research from both the motor- and verbal-learning traditions that has shown dissociable effects of practice variability on learning and performance.

운동 학습

Motor learning

운동 학습과 연습의 가변성에 대한 연구는 예를 들어 농구 선수가 정확한 자유투를 하고 싶다면, 파울 라인 자체뿐만 아니라 파울 라인 근처의 다양한 위치에서 연습해야 한다고 제안한다. 이러한 가변 연습은 연습 중에 효과적이지 않은 것처럼 보일 수 있다. 특히 파울 라인에서만 슈팅하는 것에 비해 더 많은 성능 오류가 유발될 가능성이 높지만 장기적인 학습을 촉진할 수 있다. 나중에 자세히 논의하는 바와 같이, 연습 조건을 변경하는 것은 농구 슈팅과 같은 기술의 기초가 되는 일반적인 운동 프로그램에 익숙해지고 매개 변수를 조작하는 것을 배울 수 있기 때문에 학습에 효과적인 것으로 보인다(Schmidt, 1975). 이제 우리는 연습의 가변성을 증가시키는 것이 훈련 또는 획득 중에 더 많은 오류를 야기하는 동시에 장기적인 학습 혜택을 줄 수 있다는 것을 시사하는 모터 러닝 영역의 몇 가지 발견에 대해 논의한다(검토는 Guadnoli & Lee, 2004 참조).

Research on motor learning and practice variability suggests that if a basketball player, for example, wants to shoot accurate free throws, he or she should not only practice from the foul line itself but also from various positions neighboring the foul line. Such variable practice might not appear to be effective during practice—specifically, more performance errors would likely be induced relative to shooting only from the foul line—but would facilitate long-term learning. As discussed in more detail later, varying the conditions of practice seems to be effective for learning because it enables one to become familiar with, and learn to manipulate the parameters of, the general motor program underlying some skill, like shooting a basketball (Schmidt, 1975). We now discuss several findings from the motor-learning domain suggesting that increasing practice variability, while potentially inducing more errors during training, or acquisition, also has the potential to confer long-term learning benefits (for a review, see Guadagnoli & Lee, 2004).

커와 부스(1978)는 연습 조건을 고정시키는 것이 아니라 [바꾸는 것]이 운동 기술에 대한 장기적인 학습을 촉진할 수 있다는 설득력 있는 증거를 제공했다. 연구에서 아이들은 2피트, 4피트(다양한 연습) 또는 3피트(고정 연습) 거리에서 바닥에 있는 목표물을 향해 빈백을 던졌다. 잠시 후, 모든 참가자들은 고정 연습 그룹의 참가자들이 연습한 유일한 거리인 3피트 거리에서 테스트를 받았다. 직감적으로 테스트된 거리에서만 연습한 고정 연습 그룹의 참가자가 테스트된 거리에서 연습한 적이 없는 다양한 연습 그룹의 참가자들보다 더 잘할 수 있다. 그러나 결과는 정반대 패턴을 보였다. 연습 거리를 변경하면 최종 테스트에서 3피트 떨어진 곳에서 보다 정확한 토스가 이루어졌으며, 이는 반복되고 확장된 결과인 Pigott & Shapiro, 1984; Roller, Cohen, Kimball & Bloomberg, 200과 같은 다양한 연습의 이점을 보여준다.1; Wulf, 1991).

In their important article, Kerr and Booth (1978) provided compelling evidence that varying the conditions of practice, as opposed to keeping them fixed, can boost long-term learning of a motor skill. In their study, children tossed beanbags at a target on the floor from distances of 2 and 4 feet (varied practice) or only 3 feet (fixed practice). After a delay, all participants were tested from a distance of 3 feet, the sole distance practiced by participants in the fixed-practice group. Intuition would suggest that participants in the fixed-practice group, who exclusively practiced from the tested distance, would do better than those in the varied-practice group, who never practiced at the tested distance. The results, however, showed the opposite pattern: Varying the practice distances led to more accurate tosses from 3 feet away on the final test, showcasing the benefits of variable practice in producing transfer of a motor skill, a result that has been replicated and extended (e.g., Pigott & Shapiro, 1984; Roller, Cohen, Kimball, & Bloomberg, 2001; Wulf, 1991).

[변화주기 연습]은 농구 슈팅(Landin, Hebert, & Fairweather, 1993)과 포핸드 라켓 기술 습득(Green, Whitehead, Sugden, 1995)과 같은 다른 복잡한 운동 기술의 학습을 촉진할 수 있다. 농구 연구에서, 두 그룹의 참가자들은 3일 동안 농구 자유투를 쏘는 연습을 했다. 고정 연습 조건에서는 참가자들이 기준 거리인 12피트에서만 자유투를 쏜 반면 가변 연습 조건의 참가자들은 기준 거리뿐만 아니라 다른 두 거리(8피트와 15피트)에서도 쐈다. 중요한 것은 두 그룹이 연습한 총 자유투 횟수(120개)가 동일하다는 것이다. 연습 단계로부터 72시간 후에 시행된 유지 테스트는 참가자들이 기준 거리(12피트)에서 10개의 자유투를 쏘는 것으로 구성되었다. 상식적인 예측은 고정 연습 조건의 참가자들이 가변 연습 조건의 참가자들에 비해 그 거리에서 더 많은 자유투를 연습했기 때문에 최종 시험에서 더 많은 자유투를 할 것이라는 것이다. 그러나 직관에 반하는 연구 결과는 가변 연습 조건의 참가자들이 지연 유지 테스트에서 더 많은 자유투를 성공시켰다는 것이다. 여러 위치에서 연습하면 기술의 기초가 되는 일반 운동 프로그램에 더 익숙해질 수 있음을 시사했다.

Subsequent research found that variable practice can foster the learning of other complex motor skills, such as shooting a basketball (Landin, Hebert, & Fairweather, 1993) and mastering a forehand racket skill (Green, Whitehead, & Sugden, 1995). In the basketball study, two groups of participants practiced shooting basketball free throws over a period of 3 days. In the fixed-practice condition, participants shot the free throws exclusively from the criterion distance of 12 feet, whereas participants in the variable-practice condition shot from the criterion distance as well as from two other distances (8 feet and 15 feet). It is important to note that the total number of free throws (120) practiced by both groups was equated. The retention test, administered 72 hr after the practice phase, consisted of participants shooting 10 free throws from the criterion distance (12 feet). Again, the commonsense prediction would be that participants in the fixed-practice condition would make more free throws on the final test because they practiced more free throws from that distance compared with participants in the variable-practice condition. The counterintuitive finding, however, was that participants in the variable-practice condition made more free throws on the delayed-retention test, suggesting that practicing from multiple locations engendered more familiarity with the general motor program underlying the skill.

단순한 [운동 기술의 학습]은 그러한 연습이 [획득 성능acquisition performance]에 해로운 영향을 미치는 경우에도 연습 조건의 변화로부터 이익을 얻는 것으로 반복적으로 나타났다. 이러한 학습-성과 상호작용 효과를 창출한 많은 연구는 타이밍 기술을 조사했다(예: Catalano & Kleiner, 1984; Hall & Magill, 1995; Lee, Magill, & Weeks, 1985; Wrisberg & Mead, 1983; Wulf & Schmidt, 1988). 예를 들어, 한 연구에서, 참가자들은 정확히 200ms 안에 그렇게 하는 것을 목표로 주어진 시작 지점에서 팔로 장벽을 넘어뜨리려고 시도했다. 변수 그룹은 4개의 다른 출발 지점(15, 35, 60, 65cm)에서 연습하는 반면, 상수 그룹은 항상 같은 출발 지점(예: 60cm)에서 연습한다. 그림 3에 표시된 것처럼, 변수 그룹은 획득 중에 일정한 그룹보다 더 나쁜 성능을 보였으며, 목표 시간 200ms 내에 암 이동을 시도할 때 더 많은 절대 오류를 발생시켰지만, 이후 새로운 시작 지점(50cm)을 테스트한 즉시 및 지연(1일) 전달 테스트에서 더 나은 학습을 보였다(McC).Racken & Stelmach, 1977). 유사한 학습-성과 상호작용은 기준 손잡이 힘을 학습하는 데 있어 가변 연습의 영향을 조사한 연구에서 나타났다. 기준력에 도달하기 위해 연습한 참가자와 비교했을 때, 추가 손잡이 힘을 연습한 참가자는 [획득 중에 기준력]에 도달하는 데 더 나쁜 성과를 보였지만 [지연 후 기준력]을 생성하는 데 더 정확했다(C. H. Shea & Kohl, 1991년). 또한 C를 참조한다. H. Shea & Kohl, 1990).

The learning of simpler motor skills has also been repeatedly shown to benefit from varying the conditions of practice, even in cases when such practice has detrimental effects on acquisition performance. Many of the studies that have produced this learning–performance interaction effect have examined timing skills (e.g., Catalano & Kleiner, 1984; Hall & Magill, 1995; Lee, Magill, & Weeks, 1985; Wrisberg & Mead, 1983; Wulf & Schmidt, 1988). For example, in one study, participants attempted to knock over a barrier with their arm from a given starting point, with the goal of doing so in precisely 200 ms. A variable group practiced from four different starting points (15, 35, 60, and 65 cm), whereas a constant group always practiced from the same starting point (e.g., 60 cm). As displayed in Figure 3, the variable group performed worse than the constant group during acquisition, producing more absolute errors when attempting to execute the arm movement in the target time of 200 ms, yet showed better learning on subsequent immediate and delayed (1 day) transfer tests in which a new starting point (50 cm) was tested (McCracken & Stelmach, 1977). A similar learning–performance interaction was shown in a study that examined the effects of variable practice in learning a criterion handgrip force. Compared with those who practiced solely to reach the criterion force, participants who practiced additional handgrip forces performed worse during acquisition at reaching the criterion force but were more accurate in producing the criterion force after a delay (C. H. Shea & Kohl, 1991; see also C. H. Shea & Kohl, 1990).

구두 학습

Verbal learning

학생들에게 정기적으로 제공되는 오래되고 널리 알려진 조언 중 하나는 조용한 장소(예를 들어 도서관의 단골 코너)를 찾아 그곳에서 꾸준히 공부하라는 것입니다. 학습 조건을 일정하게 유지하는 것이 학습에 도움이 된다고 생각된다. 그러나 운동 영역의 발견과 유사하게, 연구 결과에 따르면, 연구 세션 중 변화를 유도하는 것(예: 기억해야 할 자료가 연구되는 환경적 맥락의 변화 또는 해결해야 할 문제의 변화 증가)도 언어 학습에 도움이 될 수 있다. 그러한 변화를 유도하는 것은 종종 획득 성능에 무시해도 될 정도의 영향을 미치거나 심지어 이를 방해할 수도 있지만, 소재가 나중에 해당 소재에 쉽게 접근할 수 있는 광범위한 기억 신호와 연관되기 때문에 장기적인 학습을 향상시킬 수 있다. 언어 학습 전통의 여러 연구들이 이것을 경험적으로 증명해 왔다.

One long-standing and widespread piece of advice regularly given to students is to find a quiet location—say, a favorite corner of the library—and to study there on a consistent basis. Keeping study conditions constant, it is thought, benefits learning. However, analogous to findings in the motor domain, studies have shown that inducing variation during study sessions—for example, by varying the environmental context in which to-be-remembered material is studied or increasing the variation of to-be-solved problems—can also benefit verbal learning. Inducing such variation often has negligible effects on acquisition performance, or may even impede it, but it can enhance long-term learning because the material becomes associated with a greater range of memory cues that serve to facilitate access to that material later. Several studies in the verbal-learning tradition have demonstrated this empirically.

한 연구는 자료를 학습하는 물리적 맥락 또는 환경을 변경하는 것이 새로운 맥락에서 해당 자료를 시험볼 때 학습을 강화할 수 있는지 여부를 조사했다. 이는 현대의 표준화된 테스트(예: SAT, GRE)가 종종 낯선 위치에서 시행된다는 점을 고려할 때 여전히 관련성이 있는 문제이다. 참가자들은 먼저 40개의 단어 목록을 연구했다. 참가자의 절반은 미시간 대학 캠퍼스의 특정 장소인 A룸에서, 다른 참가자는 미시건 캠퍼스의 다른 장소인 B룸에서 목록을 연구했습니다. 3시간 후, 각 그룹의 참가자 중 절반은 같은 방에서 단어를 다시 읽었고, 다른 참가자들은 다른 장소에서 목록을 다시 살펴보았다. 두 번째 스터디 세션 후 3시간 후에 시행된 최종 테스트에서 모든 참가자는 중립 위치인 C실에서 단어에 대한 테스트를 받았다. 놀랍게도, 다른 방에서 공부한 참가자들은 같은 방에서 공부한 참가자보다 약 21% 더 많은 단어를 기억했으며, 가변 연습의 기억력 이점을 보여주었다(Smith, Glenberg, Bjork, 1978). 따라서, 참가자들이 새로운 장소에서 물리적 연구 환경을 변화시키면서 시험을 치른 경우, 나중에 동일하거나 유사한 자료를 사용하여 복제한 결과인 학습을 강화했다(Glenberg, 1979; Smith, 1982). 또 다른 연구는 모든 강의가 같은 장소에서 진행되는 것에 비해 4개의 다른 장소에서 연속적으로 4개의 강의를 한 후 참가자들이 통계 개념을 5일 동안 유지하는 것이 더 낫다는 것을 보여줌으로써 보다 복잡한 학습 자료로 이 연구 결과를 복제했다. 그러나 각 통계 강의 직후에 시행된 단기 보존 테스트의 성과는 두 그룹 모두에서 유사했다(Smith & Rothkopf, 1984).

One study examined whether varying the physical context, or environment, in which material is studied can bolster learning when that material is tested in a new context, an issue that remains relevant given that modern standardized tests (e.g., SAT, GRE) are often administered in unfamiliar locations. The participants first studied a list of 40 words. Half the participants studied the list in Room A, a particular location on the University of Michigan campus; the other participants studied the list in Room B, a different location on the Michigan campus. Three hours later, half of the participants in each group restudied the words again in the same room, whereas the other participants studied the list again in the other location. On the final test, administered 3 hr after the second study session, all participants were tested on the words in a neutral location, Room C. Strikingly, participants who studied in different rooms recalled approximately 21% more of the words than participants who studied in the same room, demonstrating the mnemonic benefit of variable practice (Smith, Glenberg, & Bjork, 1978). Thus, if participants were tested in a novel location, varying the physical study environments bolstered learning, a finding that was later replicated using the same or similar materials (Glenberg, 1979; Smith, 1982). Another study replicated this finding with more complex learning material by showing that participants’ 5-day retention of statistical concepts was better when it occurred after four successive lectures given in four different locations as opposed to when all of the lectures were given in the same location. Performance on short-term retention tests administered immediately after each statistics lecture, however, was similar for both groups (Smith & Rothkopf, 1984).

환경 컨텍스트의 변동을 증가시킬 뿐만 아니라, 반드시 단기적인 성과는 아니지만 장기적인 학습과 이전도 획득 단계에서 문제의 변동을 증가시킴으로써 이익을 얻을 수 있다. 예를 들어, 화학 공정 공장의 컴퓨터 기반 시뮬레이션 문제 해결과 관련된 과제에 대한 가변 관행의 영향을 조사한 연구에서, 참가자들은 "전이 역설"을 나타내는 결과 패턴을 생성했다. 특히, [낮은 가변성 문제]와 비교하여 [매우 가변적인 연습 문제]는 연습 중에 더 많은 [수행] 오류를 유발했지만, 이후 테스트에서 해결된 새로운 문제 수에서 입증되었듯이 [학습]에 긍정적인 영향을 미쳤다(Van Merrienboer, de Crook, & Jelsma, 1997). 이러한 부호화의 가변성은 또한 유추적 추론(Gick & Holyoak, 1983)과 기하학적 문제 해결(Paas & Van Merrienboer, 1994), 텍스트 자료(Mannes & Kintsch, 1987)와 얼굴-이름 쌍의 보존(Smith & Handy, 2014)을 강화하는 것으로 나타났다.

In addition to increasing the variation of the environmental context, long-term learning and transfer but not necessarily short-term performance can also profit from increasing the variation of problems during an acquisition phase. For example, in a study that examined the effects of variable practice on a task that involved troubleshooting a computer-based simulation of a chemical process plant, participants produced a pattern of results indicative of a “transfer paradox.” Specifically, highly variable practice problems, relative to low-variability problems, induced more performance errors during practice but had positive effects on learning, as evidenced by the number of new problems solved on a later test (Van Merrienboer, de Croock, & Jelsma, 1997). Such encoding variability has also been shown to enhance analogical reasoning (Gick & Holyoak, 1983) and geometrical problem solving (Paas & Van Merrienboer, 1994), as well as the retention of text material (Mannes & Kintsch, 1987) and face–name pairs (Smith & Handy, 2014).

언어 자료로 가변 연습의 학습 이점을 입증한 또 다른 연구에서, 참가자들은 나중에 테스트된 아나그램을 반복적으로 풀거나(예: 연습 단계에서 LDOOF가 세 번 풀리고 테스트에 나타났음) 테스트된 아나그램의 여러 버전을 풀어서 아나그램을 푸는 연습을 했다.d나중에 (예를 들어 DOLOF, FOLOD 및 OOFLD가 실행되었고 LDOF가 테스트에 나타났다.) 관심사는 아나그램의 여러 변형을 해결하는 것, 즉 문제의 가변성을 높이는 것이 나중에 아나그램을 푸는 참가자들의 능력을 향상시킬 수 있는가 하는 것이었다. 실제로 가변 연습 조건의 참가자들은 연습 단계에서 아나그램을 해결하는 데 비교적 오랜 시간이 걸리고 단기적인 수행 저하가 드러났지만, 그들은 이후 테스트에서 상대적으로 더 많은 아나그램을 풀었다(M. K. Goode, Geraci, & Roediger, 2008). 운동 학습에 대한 이전 섹션에서 검토한 결과 중 몇 가지와 마찬가지로, 이 결과는 직관적이지 않다. 왜냐하면 가변 실습 그룹은 나중에 테스트된 특정 아나그램을 해결하려고 시도하지 않은 반면, 다른 그룹은 연습 단계에서 세 번 풀었기 때문이다. 따라서 이러한 결과는 [테스트 받지 않을 다양한 거리에서 목표물]을 던지는 것이 [테스트 받을 거리]에서만 그러한 연습하는 것보다 학습에 더 낫다는 커와 부스의 운동 학습 실험의 결과를 개념적으로 복제한다.

In yet another study that demonstrated learning benefits of variable practice with verbal materials, participants practiced solving anagrams by either repeatedly solving the anagram that was tested later (e.g., LDOOF was solved three times during the practice phase and appeared on the test) or solving multiple versions of the anagram that was tested later (e.g., DOLOF, FOLOD, and OOFLD were practiced and LDOOF appeared on the test). Of interest was whether solving multiple variants of the anagram—that is, increasing the variability of the problems—would enhance participants’ ability to solve the anagrams later. Indeed, despite participants in the variable practice condition taking relatively longer to solve the anagrams during the practice phase, revealing a short-term performance decrement, they solved relatively more of the anagrams on a later test (M. K. Goode, Geraci, & Roediger, 2008). Like several of the results reviewed in the previous section on motor learning, this result is counterintuitive because the variable practice group never attempted to solve the specific anagram that was later tested, whereas the other group solved it three times during the practice phase. Thus, these results conceptually replicate the outcome of Kerr and Booth’s (1978) motor-learning experiment, in which tossing beanbags at a target from various nontested distances was better for learning than practicing those tosses from the tested distance.

요약

Summary

단순하고 복잡한 운동 기술의 장기 보존 및 이전은 훈련 중 수행에 무시할 수 있거나 부정적인 영향을 미칠 수 있는 연습에도 불구하고, 그러한 운동 기술의 단일 반복보다는 여러 번 반복을 수행하는 연습 유형에서 종종 이익을 얻습니다. 언어 학습 실험에서도 같은 것이 밝혀졌는데, 이는 해결해야 할 문제의 변화를 증가시키거나 기억해야 할 자료가 연구되는 환경적 맥락을 변화시켰다. [변화주기 연습variable practice]은 작업을 성공적으로 수행하는 데 필요한 일반적인 기초 운동 기술 또는 지식 기반에 대한 친숙함을 넓히는 것으로 보입니다.

The long-term retention and transfer of motor skills—both simple and complex—often profit from the type of practice that entails one to perform multiple iterations, rather than a single iteration, of those motor skills, despite such practice potentially having negligible or even negative effects on performance during training. The same has been revealed in verbal-learning experiments that have increased the variation of to-be-solved problems or varied the environmental context in which to-be-remembered material was studied. Variable practice, it seems, broadens one’s familiarity with the general underlying motor skill or knowledge base needed to successfully perform a task.

인출 연습

Retrieval Practice

수십 년에 걸친 연구에 따르면 테스트에 의해 촉발된 인출 프로세스는 실제로 인출된 정보를 중요한 방식으로 변화킨다. 즉, 테스트는 [메모리에 저장된 내용에 대한 수동적 평가]일 뿐만 아니라(종종 교육에서 전통적인 관점처럼), [메모리에 저장된 내용을 수정하는 매개체]로서도 작용한다. 본 절에서는 이러한 결론을 도출하는 운동 및 언어 학습 영역의 증거를 검토한다. 예를 들어, 모터 스킬 문헌에서는, 스스로 학습한 움직임이, 외부로부터 유도되거나 단순히 관찰된 움직임보다 일반적으로 더 잘 학습된다. 마찬가지로, 언어 정보에 대한 기억을 테스트하거나 참가자들이 직접 정보를 생성하도록 하는 것은 수정 피드백이 제공되지 않는 경우에도 반복해서 읽는 것에 비해 해당 자료의 장기 보존을 향상시킵니다. 학습-수행 구별과 관련된 중요한 발견은 [종종 장기 보존을 촉진하는 인출 연습 조건]이 반대 조건과 비교하여 [단기적으로 도움이 되지 않는 것으로 보일 수 있다]는 것이다.

Decades of research suggest that the retrieval processes triggered by testing actually changes the retrieved information in important ways. That is, tests act not only as passive assessments of what is stored in memory (as is often the traditional perspective in education) but also as vehicles that modify what is stored in memory. This section reviews evidence from both the motor- and verbal-learning domains that lead to such a conclusion. In the motor-skills literature, for example, to-be-learned movements that are self-produced are typically better learned than those that are externally guided or simply observed. Likewise, testing one’s memory for verbal information, or having participants generate the information themselves, enhances long-term retention of that material compared with reading it over and over, even in cases when corrective feedback is not provided. A critical finding, relevant to the learning–performance distinction, is that conditions of retrieval practice that often facilitate long-term retention frequently may appear unhelpful in the short term compared with their counterpart conditions.

운동 학습

Motor learning

체조 플립이나 골프 스윙과 같은 운동 기술을 가르칠 때 강사가 원하는 동작을 통해 학습자를 물리적으로 지도하는 것은 흔한 일입니다. 직관적으로 이러한 유형의 지도가 유익해야 한다는 것을 알 수 있습니다. 실제로 연구 결과에 따르면 학습자가 지도 없이 기술을 생산하려고 시도할 때보다, 습득 중 수행 오류를 줄이는 것으로 나타났습니다(즉, 학습자가 스스로 기술을 습득하도록 권장됨). 문제는 지도guidance에 더 이상 의존할 수 없는 장기 학습 평가에서는 그 반대의 경우가 많다는 점이다. 즉, 가이드 없이 기술을 자주 연습하면 습득 중에 가이드를 받는 것보다 더 나은 학습을 할 수 있다(자동차 관련 작업의 지침 연구에 대한 검토는 Hodges & Campagnaro, 2012 참조). 운동 기술에 대한 장기적인 학습(반드시 단기적인 성과는 아님)은 테스트와 학습자가 기억해야 할 운동 기술을 직접 생성할 수 있는 경우(스킬을 선택하는 경우와는 달리)에서도 이익을 얻는다.

When teaching a motor skill, such as a gymnastics flip or a golf swing, it is commonplace for instructors to physically guide the learner through the desired motions. Intuition suggests that this type of instruction should be beneficial; indeed, research has shown that guiding learners reduces performance errors during acquisition compared with when learners attempt to produce the skill without guidance (i.e., are encouraged to retrieve the skill on their own). The problem is that on assessments of long-term learning when guidance can no longer be relied on, the reverse is often true—that is, practicing a skill without guidance frequently produces better learning than does being guided during acquisition (for a review on guidance research in motor-related tasks, see Hodges & Campagnaro, 2012). The long-term learning of motor skills, but not necessarily short-term performance, also profits from a test (as opposed to a restudy opportunity) and when learners are permitted to generate their own to-be-remembered motor skills (as opposed to when the skills are chosen for them).

가이드의 효과에 대한 초기 연구는 참가자들이 나중에 그러한 동작을 스스로 수행하도록 요청받았을 때 물리적 지원을 제공하는 것이 긍정적인 영향을 미쳤으며, 이는 초기의 가이드는 학습에 이득을 준다는 것을 시사한다. 그러나, 이러한 연구에서 유지 간격은 특히 짧았고, 따라서 장기 학습에 대한 주장은 미약했다. 수십 년이 지난 후에야 지침의 장기적 영향을 검토하는 첫 번째 연구가 등장했다. 그러한 연구에서, 참가자들은 다른 사람에 의해 신체적으로 이끌리든 그렇지 않든 간에 조이스틱 추적 과제를 연습했다. 가이드가 있는 그룹은 훈련 중 및 초기 단기 성과 테스트에서 가이드가 없는 그룹을 능가했지만, 6주 후에 실시된 후기 보존 테스트에서는 가이드가 없는 그룹이 가이드가 없는 그룹보다 더 나은 학습을 보여주었다. 또한, 유도 그룹은 과제를 수행한 적이 없고 단순히 지켜본 참가자 그룹보다 더 잘 유지되는 것을 보여주지 못했다(Baker, 1968; 암스트롱, 1970 참조).

Early research on the effects of guidance (e.g., Melcher, 1934; Waters, 1930) showed that providing physical assistance during the acquisition of simple to-be-learned movements had positive effects when participants were subsequently asked to perform those movements on their own, suggesting that learning profits from initial guidance. However, the retention intervals in these studies were particularly short, and thus any claims of long-term learning were tenuous. It was not until decades later that the first studies to examine the long-term effects of guidance emerged. In one such study, participants practiced a joystick pursuit-tracking task while either being physically guided by another person or not. The guided group outperformed the unguided group during training and on initial short-term performance tests, but on a later retention test administered 6 weeks later, the unguided group demonstrated better learning than the guided group. Furthermore, the guided group failed to show better retention than a group of participants who had never performed the task but simply watched (Baker, 1968; see also Armstrong, 1970).

후속 연구는 가이드의 학습 및 성과 효과를 복제하고 확장했습니다. 예를 들어, 레버를 다양한 위치로 조작하는 작업과 관련하여, 물리적으로 유도된 그룹은 획득 중에 더 잘 수행했지만(즉, 성능 오류를 줄였다) 유지 간격 후에는 안내되지 않은 그룹에 비해 더 악화되었다(Winstein, Pohl, & Lewthwaite, 1994). 마찬가지로, 암 확장이 포함된 격월별 조정 작업 훈련 중 안내 연습은 성과 오류를 방지했다. 그러나 부분 지침이 제공되거나 지침이 제공되지 않은 조건에 비해 장기 학습이 덜 이루어졌다(Feijen, Hodges, & Beeek, 2010; Tsutsui & Imanaka, 2003 참조). 마지막으로, 하네스(harness)가 크리켓 스포츠와 관련된 볼링 기술을 적절히 수정하는 데 도움이 될 수 있는지 여부를 조사한 연구에서, 하네스(harness)가 적용된 제한은 단기적으로는 기술을 개선했지만, 하네스(harness)를 사용하지 않았을 때와 비교하여 어떠한 장기적 학습 이익도 창출하지 못한 것으로 밝혀졌다. 명백히, 훈련 중 가이드가 학습에 미치는 영향과 수행에 미치는 영향은 다를 수 있다.

Subsequent research has replicated and extended the learning and performance effects of guidance. For example, on a task that involved manipulating a lever to various positions, a physically guided group performed better during acquisition (i.e., made fewer performance errors) but worse after a retention interval, relative to an unguided group (Winstein, Pohl, & Lewthwaite, 1994). Likewise, during training of a bimanual coordination task that involved arm extensions, guided practice prevented performance errors; however, it also yielded less long-term learning compared with conditions in which partial guidance or no guidance was provided (Feijen, Hodges, & Beek, 2010; see also Tsutsui & Imanaka, 2003). Finally, in a study that examined whether a harness could serve as an aid to properly modify the bowling technique involved in the sport of cricket, it was found that the restriction applied by the harness improved techniques in the short term but failed to yield any long-term learning benefits, compared with when no harness was used (Wallis, Elliot, & Koh, 2002). Clearly, guidance during training can have differential effects on learning and performance.

[인출 연습]이 학습과 성과에 미치는 영향을 검토하는 또 다른 간단한 방법은 학습자가 먼저 학습한 기술을 관찰한 후 학습자를 테스트(즉, 스스로 기술을 복제하거나 검색하도록 요구함)하거나 재현할 필요 없이 기술을 다시 제시할 수 있도록 하는 것입니다. 그 후 시행된 테스트는 재표현 시험과 관련하여 검색 관행이 학습을 향상시키는지 여부를 밝혀낼 수 있다. 모터러닝 영역의 경험적 연구가 검색 관행의 잠재적인 이점을 더 잘 이해하기 위해 이러한 방법을 사용했다는 것은 놀라운 일이다. 주목할 만한 예외로, 한 연구는 팔 위치 결정 작업을 학습하는 데 인출 연습의 영향을 조사했다. 학습한 자세에 대한 초기 프레젠테이션 후, 참가자들은 그 위치에서 여러 번 테스트를 받았거나 테스트를 거치지 않고 반복적으로 재제시되었다. 인출 연습을 한 참가자는 단순히 여러 번 관찰한 참가자에 비해 팔 자세를 장기간 유지하는 것이 더 좋았다. 그러나 습득acquisition 과정에서 수행을 평가할 때는 그 반대였다(Hagman, 1983). 후속 모터 기술 연구는 이러한 유형의 [인출 연습이 제공하는 장기적 학습 이점]을 재현했다(즉, 테스트 대 재학습; Boutin et al., 2012; Boutin, Panzer, & Blandin, 2013).

Another, rather simple way to examine the effects of retrieval practice on learning and performance is to allow learners to first observe the to-be-learned skill and then either test the learners (i.e., require them to reproduce, or retrieve, the skill on their own) or present the skill again without the requirement to reproduce it. A subsequently administered test could then reveal whether retrieval practice, relative to re-presentation trials, enhances learning. It is surprising that scant empirical work in the motor-learning domain has used this sort of method to better understand the potential benefits of retrieval practice. Representing a notable exception, one study examined the effects of retrieval practice on learning an arm-positioning task. After an initial presentation of to-be-learned positions, participants either were tested on the positions several times or were simply re-presented with them over and over without being tested. Participants who engaged in retrieval practice showed better long-term retention of the arm positions than those who simply observed the positions multiple times. The opposite was true, however, when performance was assessed during acquisition (Hagman, 1983). Subsequent motor-skills research replicated the long-term learning benefits conferred by this type of retrieval practice (i.e., testing vs. restudying; Boutin et al., 2012; Boutin, Panzer, & Blandin, 2013).

마지막으로, 운동 기술의 학습은 다른 형태의 인출 연습으로부터 이익을 얻습니다. 즉, 학습자에게 동작을 선택해주기보다, [학습자가 자신의 동작을 생성할 수 있도록] 합니다. 이 사전 선택 효과에 대한 가장 초기적이고 가장 설득력 있는 시연 중 하나에서, 참가자들은 이전에 스스로 선택했거나 실험자가 부과한 빠른 팔 움직임을 재현했다. 획득 단계에서 그러한 장기 학습의 지표를 수집할 수 없음에도 불구하고, 신속성과 정밀도 측면에서 팔 움직임을 유지하는 것은 선택 그룹에 유리하다. (Stelmach, Kelso, Wallace, 1975) 사전 선택 효과는 모터 학습 문헌에서 가장 강력하고 신뢰할 수 있는 효과 중 하나로 빠르게 나타났다(Martenuik, 1973 참조, 조기 검토는 Kelso & Wallace, 1978 참조).

Finally, the learning of motor skills profits from another form of retrieval practice—namely, permitting learners to generate their own to-be-learned movements as opposed to the movements being selected for them. In one of the earliest and most convincing demonstrations of this preselection effect, participants reproduced rapid arm movements that were either previously selected by themselves or imposed by the experimenter. Retention of the arm movements—in terms of both rapidity and precision—favored the selection group, even though no indicators of such long-term learning could be gleaned from the acquisition phase (Stelmach, Kelso, & Wallace, 1975). The preselection effect quickly emerged as one of the most robust and reliable effects in the motor-learning literature (see also Martenuik, 1973; for an early review, see Kelso & Wallace, 1978).

구두 학습

Verbal learning

운동 학습 영역의 연구와 마찬가지로, 언어 자료의 인출 연습(또는 테스트)을 조사하는 경험적 작업은 수십 년 전으로 거슬러 올라가며, 그 중에서 기억에서 정보를 인출하는 것은 단순히 정보가 기억 속에 존재한다는 것을 드러내는 것 이상을 한다는 공감대가 형성되었다. 실제로 검색 행위는 성공적으로 검색된 정보를 미래에 더 기억하기 쉽게 만든다는 점에서 "기억 수정자memory modifier"(R. A. Bjork, 1975)이며, 광범위한 소재와 결과를 사용하여 수명 전체에 걸쳐 입증된 [테스트 효과]라고 불리는 발견이다. 측정(검토 내용은 Carpenter, 2012; Roediger & Butler, 2011; Roediger & Karpicke, 2006a 참조). 다시 말해, 인출 연습은 그 자체로 [강력한 학습 사건]입니다. 그러나 단기적으로, 인출 연습은 종종 테스트 대신 재료가 재처리되는 조건에 비해 기억의 이점을 제공하지 못하는 것으로 보인다. 우리는 이제 학습과 수행의 구별을 필요로 하는 언어 학습 영역의 인출 연습에 대한 작업을 고려합니다.

Similar to the research in the motor-learning domain, empirical work investigating retrieval practice (or testing) of verbal material dates back decades, out of which has emerged the consensus that retrieving information from memory does more than simply reveal that the information exists in memory. In fact, the act of retrieval is a “memory modifier” (R. A. Bjork, 1975) in the sense that it renders the successfully retrieved information more recallable in the future than it would have been otherwise, a finding that has been termed the testing effect, which has been demonstrated across the life span using a wide range of materials and outcome measures (for reviews, see Carpenter, 2012; Roediger & Butler, 2011; Roediger & Karpicke, 2006a). In other words, retrieval practice is itself a potent learning event. In the short term, however, retrieval practice often appears to fail to confer any mnemonic benefits compared with conditions in which the material is restudied instead of tested. We now consider work on retrieval practice in the verbal-learning domain that has necessitated the distinction between learning and performance.

테스트 효과에 대한 최초의 대규모 연구는 게이츠(1917년)와 스피처(1939년)로 거슬러 올라갈 수 있지만, 1970년대에 이르러서야 연구자들은 검색 연습이 학습과 성과에 차이를 가져올 수 있다는 설득력 있는 증거를 제공했다. 예를 들어, 한 연구에서 참가자들은 40개의 단일 단어를 세 번 공부한 후 SSST(자유 리콜 테스트)를 치르거나 세 번 프리 리콜 테스트(STT)를 치렀습니다. 두 그룹이 모두 테스트된 이 절차의 네 번째 단계에서 SST 조건에 할당된 참가자들은 STTT 조건의 참가자들보다 더 큰 단기 호출 성능을 보였다. 즉, 반복 연구가 반복 테스트보다 더 좋았다. 그러나 이틀 후 평가된 장기 리콜은 STTT 조건을 선호했다(Hogan & Kintsch, 1971). 이 연구결과는 나중에 반복 연구가 5분 후 반복 테스트보다 더 나은 리콜로 이어졌지만(50% 대 28%), 2일 후 실시된 지연 리콜 테스트에서 반복 테스트가 비록 미미하지만 반복 연구를 능가한다는 연구 결과에서 반복 테스트보다 더 잘 재현되고 확장되었다(25% 대 23%; Thompson, Wenger, & Bartling, 1978). 같은 해, 확장된 간격 테스트 스케줄은 동등한 간격 테스트 스케줄보다 학습된 이름을 더 잘 기억하는 것으로 확인되었지만, 이 두 조건 모두 주어진 프레젠테이션 직후에 여러 테스트를 연속적으로 시행하는 대량 테스트 조건보다 더 나은 장기 학습으로 이어졌다. 이름, 획득 단계에서 거의 오류 없는 성능을 보인 조건입니다(Landauer & Bjork, 1978).

Although the first large-scale studies on the testing effect can be traced back to Gates (1917) and Spitzer (1939), it was not until the 1970s that researchers provided compelling evidence that retrieval practice can have differential effects on learning and performance. In one study, for example, participants studied 40 single words either three times before taking a free-recall test (SSST) or once before taking three free-recall tests (STTT). During the fourth phase of this procedure in which both groups were tested, participants assigned to the SSST condition showed greater short-term recall performance than those in the STTT condition—in other words, repeated studying was better than repeated testing. Long-term recall assessed 2 days later, however, favored the STTT condition (Hogan & Kintsch, 1971). These findings were later replicated and extended in a study that found that repeated studying led to better recall than repeated testing after 5 min (50% vs. 28%) but that repeated testing trumped repeated studying, albeit only slightly, on a delayed recall test administered 2 days later (25% vs. 23%; Thompson, Wenger, & Bartling, 1978). That same year, expanded-interval testing schedules were found to produce better recall of to-be-learned names than equal-interval testing schedules, but both of these conditions led to better long-term learning than did a massed-testing condition, in which several tests were administered in succession immediately after the presentation of a given name, a condition that showed nearly errorless performance during the acquisition phase (Landauer & Bjork, 1978).

[인출 연습]과 관련하여 학습 성과 상호 작용에 대한 설득력 있는 데모를 제공한 다른 연구에서, 한 그룹의 참가자(반복 연구)는 40단어 목록을 5회 연속(SSSS) 학습한 반면, 다른 그룹(반복 테스트)은 4회 연속 리콜 테스트(STTT) 전에 목록을 한 번 학습했다. 최종 리콜 테스트는 5분 또는 1주일 후에 (각 그룹의) 다른 그룹의 참가자들에게 시행되었다. 반복 스터디 그룹은 즉시(5분) 테스트에서 반복 테스트 그룹을 큰 폭으로 앞섰지만, 지연된 (1주일) 테스트에서는 반대 패턴이 관찰되었다. 구체적으로는 반복 테스트가 반복 연구보다 더 나은 장기 보존으로 이어졌다. 또한 시간이 지남에 따라 잊어버리는 것이 반복 학습 그룹에서 반복 실험 그룹보다 훨씬 더 두드러졌기 때문에 시험이 기억을 안정시키는 데 도움이 된다는 것이 분명했다. 1주일 리콜을 5분 리콜의 백분율로 구체적으로 고려할 때, 반복 학습과 반복 테스트가 각각 약 75%, 30%의 망각과 관련이 있다는 것을 발견했다(Wheeler, Ewers, & Buonanno, 2003).

In another study that provided a convincing demonstration of a learning-performance interaction as it relates to retrieval practice, one group of participants (repeated study) studied a 40-word list five consecutive times (SSSSS), whereas another group (repeated test) studied the list once before four consecutive recall tests (STTTT). Final recall tests were then administered to different groups of participants (from each group) after 5 min or 1 week. The repeated-study group outperformed the repeated-test group by a large margin on the immediate (5 min) test, but on the delayed (1 week) test, the opposite pattern was observed—specifically, repeated testing led to better long-term retention than did repeated studying. It was also clear that testing helped stabilize memory, as forgetting over time was far more pronounced in the repeated-study group than the repeated-test group. When specifically considering 1-week recall as a percentage of 5-min recall, researchers found that repeated studying and repeated testing were associated with approximately 75% and 30% forgetting, respectively (Wheeler, Ewers, & Buonanno, 2003).

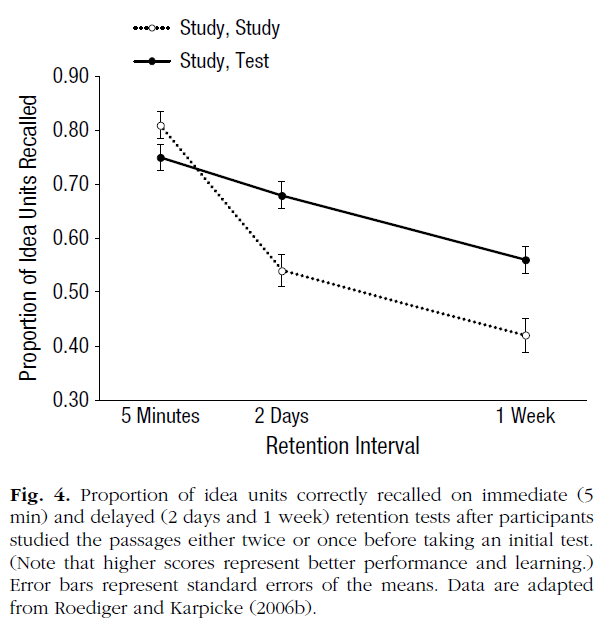

지금까지 우리는 비교적 단순한 학습 자료(예: 단일 단어, 단어 쌍)를 사용한 테스트 효과에 대한 연구를 검토했다. 그러나 교육적으로 관련된 자료를 더 많이 사용할 경우 검색 연습이 학습과 성과에 차이를 줄 수 있다는 것도 분명하다. 그러한 연구 중 하나는 참가자들이 태양과 해달과 같은 일반적인 주제를 다루는 산문 구절을 처음 연구하는 것이었다. 한 가지 조건에서는 참가자들이 전체 지문을 다시 공부한 반면, 다른 조건에서는 참가자들이 피드백 없이 연구된 자료를 기억하는 능력에 대해 테스트를 받았다. 그런 다음 5분, 2일 또는 1주일 후에 각 조건의 다른 참가자 그룹에 최종 리콜 테스트를 시행했다. 그림 4와 같이 결과는 명확합니다. 5분 후, 지문을 다시 공부한 참가자들은 피드백 없이 중재 시험을 치른 참가자들보다 기억력이 더 좋았다. 그러나 지연된 보존 테스트에서는 테스트 그룹이 restudy 그룹보다 2일 1주 후에 더 많은 자료를 인출하는 등 상당한 반전이 있었으며, 이 결과는 이후 연구의 두 번째 실험에서 복제되고 확장되었다(Roediger & Karpicke, 2006b). 이 연구(및 이와 유사한 다른 연구)의 결과가 특히 인상적인 것은 최초 테스트 중에 테스트 조건의 참가자에게 피드백이 제공되지 않았다는 것이다. 즉, 시험 조건의 참가자는 처음에 기억할 수 있는 소재(약 70%)에만 재노출되었다. 반면, restudy 상태의 참가자들은 최종 보존 테스트 전에 전체 통로에 다시 노출되었다. 이러한 단점에도 불구하고, 테스트 그룹의 참가자들은 장기적으로 더 많은 정보를 보유했다.

Thus far, we have reviewed studies on the testing effect that have used relatively simple learning materials (e.g., single words, word pairs); however, it is also clear that retrieval practice can have differential effects on learning and performance when more educationally relevant materials are used. One such study involved participants first studying prose passages covering general topics, such as the sun and sea otters. In one condition, participants then restudied the passage in its entirety, whereas in another condition, participants were tested, without feedback, for their ability to recall the studied material. Final recall tests were then administered to different groups of participants from each condition after 5 min, 2 days, or 1 week. The results, which are shown in Figure 4, are clear. After 5 min, participants who restudied the passage showed better recall performance than did participants who took an intervening test without feedback. On the delayed retention tests, however, there was a significant reversal such that the tested group recalled more of the material after 2 days and 1 week than the restudy group, a finding that was subsequently replicated and extended in the study’s second experiment (Roediger & Karpicke, 2006b). What makes the results of this study (and others like it) particularly impressive is that no feedback was given to participants in the tested condition during the initial test, which means that participants in the test condition were reexposed only to the material they were initially able to recall—approximately 70% of the passage—whereas participants in the restudy condition were reexposed to the entire passage before the final retention tests. Despite this disadvantage, participants in the tested group retained more information over the long term.

테스트 효과와 밀접하게 관련된 현상인 생성 효과generation effect에 대한 연구도 검색 관행의 장기적 학습 이점을 지적한다. 전형적인 생성 실험에서 참가자들은 학습해야 할 항목을 직접 생성하도록 요구받습니다. 예를 들어, 단어를 제시했을 때 반대되는 항목을 생성함으로써(예: hot-)--?)—또는 단순히 항목을 읽습니다(예: 긴-짧은). 그 후, 일반적으로 단서 제시(hot---)로 구성된 나중에 유지 시험이 시행된다.?, 긴----?) 및 참가자에게 대응하는 목표(콜드, 쇼트)를 상기하도록 요구합니다. Slamecka와 Graf(1978; Jacoby, 1978 참조)는 의미 기억에서 [항목을 생성하는 것]이 [단순히 읽는 것]보다 학습에 더 낫다는 것을 최초로 입증한 것으로 종종 인정된다. 이 발견은 다양한 재료, 절차 및 결과 측정을 사용하여 수백 번 반복되었다. 현재 목적에서는 참가자들이 학습 단계(거의 발생하지 않음)에서 모든 생성 항목을 성공적으로 생성할 수 없는 한 생성된 항목은 각 항목 직후에 테스트를 수행한 경우 항상 판독 항목보다 획득 성능이 떨어집니다. 이는 테스트 효과 연구에서 실패한 인출 시도와 마찬가지로, 생성 시도가 실패하면 나중에 테스트될 재료에 노출되지 않기 때문입니다. 이러한 단기적인 [수행] 측면의 장애에도 불구하고, 생성(연습)은 여전히 장기 [학습]을 강화한다.