용어의 공통된 이해를 통해 보건의료전문직교육의 과학을 발전시키기: "패컬티"라는 단어의 내용분석(Perspect Med Educ, 2022)

Advancing the science of health professions education through a shared understanding of terminology: a content analysis of terms for “faculty”

Pim W. Teunissen · Anique Atherley · Jennifer J. Cleland · Eric Holmboe · Wendy C. Y. Hu · Steven J. Durning · Hiroshi Nishigori · Dujeepa D. Samarasekera · Lambert Schuwirth · Susan van Schalkwyk · Lauren A. Maggio

소개

Introduction

용어 및 개념의 정의적 명확성이 없다면, 보건 전문직 교육(HPE) 분야의 연구자와 교육자는 오해를 초래할 위험이 있으며, 분야의 진척을 늦추고, 새로운 연구자들이 학문적 대화에 참여할 가능성을 제한한다[1]. 2021년에도 이 경고는 여전히 울려 퍼진다. 용어의 명확성 또는 공유된 이해는 HPE 전반에 걸쳐 여전히 모호하다. 예를 들어, HPE 저자들은 출판된 문헌[2, 3] 내에서 주요 개념(예: 교수 도구, 역량 기반 의료 교육)을 정의하는 가변성과 연구 팀 내에서조차 정의적 차이를 발표했다. 이 저자들은 또한 이러한 합의 부족이 의사소통의 오류에 기여하고, 주제에 대한 suboptimal한 연구를 이끌며, 이전 연구를 기반으로 하는 연구자들의 능력을 복잡하게 만들 수 있다고 강조했다. 우리의 다양한 작가 팀 내에서, 우리는 비슷한 깨달음에 도달했습니다.

Without definitional clarity of terms and concepts, researchers and educators in health professions education (HPE) research risk misunderstandings, slow the progress of the field, and limit the possibility for newcomers to engage in scholarly conversations [1]. In 2021, this warning still resonates. Clarity or a shared understanding of terminology remains elusive across HPE. For example, HPE authors have published on variability in defining key concepts (e.g., teaching tools, competency-based medical education) within the published literature [2, 3] and definitional differences even within research teams [2,3,4]. These authors also highlighted that this lack of agreement can contribute to miscommunication, lead to suboptimal research on a topic, and complicate the researchers’ ability to build on previous research. Within our diverse author team, we arrived at a similar realization.

우리의 정의적 부조화에 대한 관찰은 특정한 주제에서 비롯된 것이 아니라, 오히려 건강 전문가와 HPE 연구를 수행하는 사람들을 설명하는 데 사용되는 여러 용어와 관련이 있다. 우리의 대화는 이것이 많은 주제와 개념에 걸쳐 퍼지는 오해를 만들고 복제한다는 것을 나타내었다. 예를 들어, faculty으로 통용될 수 있는 용어와 관련하여, 우리의 유럽 작가들은 "주치의attending physician"라는 용어에 익숙하지 않은 반면, 북미에 있는 우리 중 일부는 "specialist registrar"이라는 용어에 익숙하지 않았다. 따라서 본 연구는 본 연구의 목적을 위해 [보건전문직 학습자의 교육에 기여하기 위한 교육, 평가, 멘토링, 지도와 같은 활동에 참여하는 사람(또는 사람 그룹)]으로 정의한 다양한 faculty 용어를 조사한다.

Our observation of definitional disharmony stemmed not from a particular topic, but rather related to the multiple terms that are used to describe people engaged in training health professionals and those conducting HPE research. Our conversations indicated that this creates and replicates misunderstandings that ripple across many topics and concepts. For example, regarding terms related to what may be colloquially known as faculty, our European authors were unfamiliar with the term “attending physician”, whereas those of us in North America were unfamiliar with the term “specialist registrar”. Thus, this current study investigates varieties of faculty terminology, which we defined for the purposes of this study as a person (or group of people) who engage in activities, such as teaching, assessment, mentoring, and/or supervision, intended to contribute to the education of learners in the health professions.

Faculty가 이것에 대한 일반적인 이름이지만, 같은 (개인의) 집단을 묘사하기 위해 임상 감독관, 교사, 교관, 주치의 또는 임상 직원과 같은 다른 용어들을 생각해 내는 것은 상상력이 거의 필요하지 않다.

- 그 결과, 학부 의료 프로그램의 '직장 기반 교수자'에 대한 연구와 '주치의'에 대한 또 다른 연구는 마치 서로 다른 그룹을 연구한 것처럼 보일 수 있다. 그러나, 다른 용어를 사용함에도 불구하고, 모집단 서술에 대해 세심히 살펴보면, 대학 프로그램의 직장 기반 교사들이 부속 병원의 주치의와 같다는 것을 알 수 있다.

- 반대로, 두 개의 teach-the-teacher에 초점을 맞춘 연구가 관련이 있는 것처럼 보일 수 있다. 그러나, 더 면밀한 조사를 통해 한 연구는 생물의학 과학자들에게 초점을 맞춘 반면, 다른 연구는 간호사들을 연구했음을 알 수 있다.

While faculty is a common name for this, it takes little imagination to come up with other terms—clinical supervisor, teacher, preceptor, attending physician, or clinical staff—to describe the same (groups of) individuals.

- As a result, a study on workplace-based teachers in an undergraduate medical program and another study on attending physicians might appear to study different groups, and yet, despite using different terms, a careful examination of the population description might reveal workplace-based teachers in an undergraduate program to be attending physicians at an affiliated hospital.

- Alternatively, two studies focusing on teach-the-teacher programs might seem related. However, closer inspection could show faculty in one study focused on biomedical scientists while another examined nurse practitioners.

우리 분야에서 [연구 참여자들의 다양성]이, [연구 참여자 풀을 설명하는 데 필요한 명확한 지침의 부족]과 결합되어, 기존 연구를 기반으로 축적해가는 우리의 능력을 저해하고, 연구 정보에 입각한 이론의 발전에 대한 기여를 저해하고, 최적의 교육적 실천의 제공을 저해한다.

Our field’s diversity of research participants, combined with a lack of clear guidance on what is helpful in describing one’s research participant pool, inhibits our ability to build on previous work, contribute to the development of research-informed theory, and provide optimal educational practice.

이 연구에서 우리는 세 가지 목표를 가지고 있다:

- 1) 생물의학 문헌(HPE 논문 포함)에서 "faculty"을 설명하기 위해 사용되는 용어를 분석하고 보고한다.

- 2) 과학 출판물에 자신의 연구 참가자를 설명할 때 연구자와 교육이 포함해야 하는 주요 측면에 대한 지침을 템플릿 형식으로 제공한다.

- 3) HPE의 다른 주요 용어를 탐색하는 데 사용할 수 있는 반복 가능한 연구 방법을 제공한다(예: 우리가 구어적으로 의대생 및 레지던트라고 부르는 사람들을 풀어주는 것).

In this study, we have three aims:

- 1) to analyze and report the terminology used to describe “faculty” throughout the biomedical literature (including HPE papers),

- 2) to offer guidance on key aspects, in template form, that researchers and educations should include when describing one’s research participants in scientific publications, and

- 3) to provide a replicable study method that can be utilized to explore other key terms in HPE (e.g., to unpack those who we colloquially call medical students and residents).

방법들

Methods

우리는 교수진이라고 불리는 개인 또는 집단의 사람들을 묘사하는 데 사용되는 특정 단어의 존재를 식별하기 위해 저널 기사 초록의 내용 분석을 수행했다.

We conducted a content analysis of journal article abstracts to identify the presence of specific words used to describe individuals or groups of people referred to as faculty.

"faculty"이라는 용어에 대한 다양한 지리적, 문화적 관점을 제공하기 위해 다양한 배경을 가진 글로벌 작가 팀을 구성하였습니다. 작가들의 다양한 지리적 위치 때문에 팀은 2018년과 2019년 유럽 의학 교육자 협회(AMEE) 연례 회의에서 직접 만나 원격 회의 소프트웨어를 통해 팀 미팅을 개최하여 프로젝트에 대한 업데이트를 제공하고 데이터의 코딩 및 분석에 대한 피드백을 받았다.

To provide a variety of geographical and cultural perspectives on the term “faculty”, we assembled a global author team with diverse backgrounds (for the distribution of the research team see Fig. S1 in Electronic Supplementary Material [ESM]). Due to authors’ diverse geographical locations, the team met in-person in 2018 and 2019 at the annual meeting of the Association of Medical Educators of Europe (AMEE) and held team meetings via teleconferencing software to provide updates on the project and receive feedback on the coding and analysis of the data.

2018년 9월 11일 PubMed에서 2007년과 2017년 사이에 출판된 의학 주제 제목(MeSH)에서 “faculty, dental”, “faculty, medical”, “faculty, nursing”, and “faculty, pharmacy” 을 포함한 좀 더 구체적인 MeSH 용어를 색인화한 기사를 검색하였다(부록 전자 참조). 국립 의학 도서관은 교수진을 "중등교육기관에서 학문적 지위를 가진 교육 및 행정 직원"으로 정의한다[5]. 우리는 검색에서 다양한 논문을 제공하지만 전문 인덱서가 "faculty"에 대해 결정한 MeSH 용어를 사용하기로 결정했다. 우리는 이 검색이 연구 교수진 또는 우리의 목표와 관련된 참가자를 언급한 모든 논문의 완전한 개요를 제공하는 것은 아니라는 것을 인정한다. 우리는 글로벌 관점을 포착하기 위해 언어를 기반으로 검색을 제한하지 않았지만, 데이터에 있는 용어가 최신인지 확인하기 위해 지난 10년으로 검색 범위를 제한했다. 향후 연구자들이 데이터베이스 액세스 우려 없이 우리의 방법을 복제할 수 있도록 무료 데이터베이스인 PubMed를 유일한 데이터베이스로 활용했다. 또한 단일의 일관된 엔티티(즉, 국립 의학 도서관)에서 생성된 MeSH 인덱싱의 일관성을 활용하기 위해 PubMed에만 초점을 맞췄다.

We searched PubMed on September 11, 2018, for articles published between 2007 and 2017 that were indexed with the Medical Subject Heading (MeSH) “faculty” and related, more specific MeSH terms including “faculty, dental”, “faculty, medical”, “faculty, nursing”, and “faculty, pharmacy” (see the Appendix in the Electronic Supplementary Material [ESM] for our search strategy). The National Library of Medicine defines faculty as “teaching and administrative staff having academic rank in a post-secondary educational institution” [5]. We decided to use MeSH terms that would provide a wide variation of papers from our search, but that were determined by professional indexers to be about “faculty”. We acknowledge that this search does not provide a complete overview of all papers that research faculty or that mentioned participants that are relevant to our aims. We did not limit our search based on language to ensure we captured global perspectives but did restrain it to the last decade to ensure that the terminology in our data was recent. We utilized PubMed, a freely available database, as our only database to enable future researchers to replicate our method without database access concerns. Additionally, we focused solely on PubMed, in order to take advantage of the consistency of MeSH indexing, which is generated from a single, consistent entity (i.e., the National Library of Medicine).

검색에서 검색된 인용문을 첨부한 메타데이터와 함께 엑셀에 다운받아 데이터 관리를 하였습니다. 메타데이터는 추상적인 텍스트(모두 영어로 되어 있음), 출판 연도, 저널, 언어, 제1저자의 위치를 포함했다. LM은 모든 제목과 초록을 선별하여 초록이 없는 인용과 faculty에 대한 역사적 서술은 제외했다.

We downloaded the citations retrieved from our search with the accompanying metadata into Excel for data management. Metadata included the abstract text (all of which is in English), publication year, journal, language, and the first author’s location. LM screened all titles and abstracts to exclude citations without abstracts and those that were historical descriptions of faculty members.

검색 결과 5,436건의 인용문이 검색됐으며, 이 중 초록이 없거나 역사적 성격의 문헌 2,082건을 제외했다. 따라서 최종 샘플에는 3,354건의 인용이 포함되어 있었습니다. 우리는 추상적인 텍스트에 초점을 맞춘 반복적인 데이터 추출 접근법을 취했다. 우선, PT와 LM은 초기 초록 검토와 토론에 따라 교수진을 위한 광범위한 작업 정의를 고안했습니다. PT와 LM은 무작위로 선정된 35개의 인용문의 추상적인 텍스트를 조사했고 각 추상 용어와 교수진을 언급한 간략한 설명에서 추출했다. 그들은 그들의 발견에 대해 토론했다. 이 예비 데이터 추출을 기반으로, 우리는 추상화에서 "faculty" 용어를 추출하는 팀의 프로세스를 안내하기 위해 초기 작업 정의를 개발했습니다. PT와 LM은 faculty를 "다른 사람이나 집단의 발전에 영향을 미치는 어떤 종류의 활동에 참여하는 사람 또는 집단"으로 정의했다. 이 작업 정의를 사용하여 7명의 프로젝트 팀 구성원(PT, LM, AA, SD, WH, JC, SvS)은 무작위로 선정된 144개의 고유한 초록으로부터 독립적으로 faculty 용어를 추출했습니다. 또한 데이터 추출을 교정하기 위해 팀원들은 동일한 초록 중 10개를 조사하여 총 154개의 초록에서 데이터를 추출했다.

The search retrieved 5,436 citations, of which we excluded 2,082 articles that did not include abstracts or were of a historical nature. Thus, our final sample included 3,354 citations. We took an iterative data extraction approach, which focused on the abstract text. To begin, PT and LM devised a broad working definition for faculty following an initial abstract review and discussion. PT and LM examined the abstract text of 35 randomly selected citations and extracted from each abstract terms and brief descriptions that referred to faculty. They discussed their findings. Based on this preliminary data extraction, we developed an initial working definition to guide our teams’ process of then extracting “faculty” terms from the abstracts. PT and LM defined faculty as: “a person or group of people who engage in some sort of activity that is intended to impact the development of another person or group”. Using this working definition, seven project team members (PT, LM, AA, SD, WH, JC, SvS) independently extracted faculty terms from 144 randomly selected, unique abstracts. Additionally, to calibrate our data extraction, team members examined 10 of the same abstracts, resulting in data extracted from a total of 154 abstracts.

PT, LM, AA는 컨퍼런스 콜을 통해 만나 그룹 용어 추출 결과와 실무 지침에 대한 피드백을 논의하였습니다. PT, LM, 그리고 AA는 개별적으로 중간 해석을 개발하고 논의했습니다. 다음으로, 모든 팀원들은 이 개정된 지침(예: 개인사를 기술하는 논문이나 조직단위를 교수진으로 기술하는 논문 등)을 사용하여 용어를 추출하도록 다시 요청받았다. 10명의 프로젝트 팀 구성원(PT, LM, AA, SD, JC, LS, HN, DS, EH 및 SvS)과 1명의 다른 사람(SvS와 함께 일하는 연구 보조)은 무작위로 선정된 40개의 고유한 초록으로부터 독립적으로 용어를 추출하여 440개의 코드화된 초록을 만들었다. 따라서 이전의 노력과 결합하여, 저자들은 이제 594개의 초록으로부터 faculty에 대한 279개의 고유한 용어를 추출했는데, 이는 표본의 총 추상 수(n = 3,354)의 17.7%에 해당한다. 최종 코딩 라운드가 작업 범주와 분석 출력에 큰 변화를 주지 않았다는 것을 알았기 때문에 우리는 여기서 멈췄다. 우리는 106개의 초록을 "null"(17.8%)로 식별했다.

PT, LM, and AA met via conference call to discuss the results of the group’s term extraction and feedback on the working guideline. PT, LM, and AA individually developed and then discussed interim interpretations. Next, all team members were again invited to extract terms using these revised guidelines (e.g., code abstract as “null” if it should be excluded with an explanation, such as: a paper describing a personal history or one describing an organizational unit as faculty [no research participants]). Ten project team members (PT, LM, AA, SD, JC, LS, HN, DS, EH, and SvS) and one other person (a research assistant working with SvS) independently extracted terms from 40 randomly selected, unique abstracts resulting in 440 coded abstracts. Thus, in combination with earlier efforts, the authors had now extracted 279 unique terms for faculty from 594 abstracts, which represented 17.7% of the total number of abstracts in our sample (n = 3,354). We stopped at this point as we noticed that the final coding round did not yield any major alterations in our working categories and analysis output. We identified 106 abstracts as “null” (17.8%).

Google Sheet를 사용하여 기술 통계의 계산을 포함하여 분석을 구성하고 용이하게 했습니다. 우리는 각 초록을 제1저자의 위치를 분류하기 위해 지리적 영역에 할당했습니다.

We used Google Sheet to organize and facilitate the analysis, including the calculation of descriptive statistics. We assigned each abstract to a geographical region to categorize the first authors’ location.

우리는 내용 분석을 사용하여 추출된 용어의 패턴과 테마를 식별했다. 내용 분석을 다음과 같이 설명된다: "질적 데이터를 환원하여 의미를 만들려는 노력으로서, 많은 질적 자료가 소요되며, 핵심 일관성 및 의미를 식별하려고 시도한다." 우선, PT, AA, 그리고 LM은 패턴이나 테마를 식별하기 위해 추출된 모든 용어를 독립적으로 여러 번 읽는다. 그 후 예비 테마는 세 번의 전화 회의 통화에서 집합적으로 논의되었고, 이는 용어 구성을 위한 작업 프레임워크로 이어졌다. PT는 콘퍼런스 콜과 국제 콘퍼런스에서 직접 미팅을 통해 작성자 팀에 이 프레임워크를 제시하여 작성자 팀의 데이터 추출 경험과 문화적 관점에 반영되도록 하였다. 별다른 변화는 필요하지 않았다.

We used content analysis to identify patterns and themes in the extracted terms. Content analysis is described as a “qualitative data reduction and sense making effort that takes a volume of qualitative material and attempts to identify core consistencies and meanings” [6, p. 541]. To start, PT, AA, and LM independently read all extracted terms multiple times to identify patterns or themes. Preliminary themes were then discussed collectively in three teleconference calls, which resulted in a working framework for organizing the terms. PT presented this framework to the author team via conference call and an in-person meeting at an international conference to ensure that the framework resonated with the author team’s experience of data extraction and their cultural perspectives. No significant changes were necessary.

결과.

Results

요약본은 처음에 추출된 3,354개의 기사에서 93개국 중 54개국을 대표하는 제1저자에 의해 작성되었다. 우리 표본의 기사는 주로 영어로 작성되었으며(90.9%) 260개 저널에 게재되었다. 코드화된 594개의 초록 중 대다수(n = 346)는 북미에 기반을 둔 제1저자(58.25%)에 의해 출판되었으며(전자 보충 자료 [ESM]의 표 S1 참조), 그 중 305개는 미국과 캐나다에 있었다(n = 41).

Abstracts were written by first authors representing 54 of 93 countries in the 3,354 articles initially extracted. The articles in our sample were predominantly written in English (90.9%) and published in 260 journals. Of the 594 abstracts coded, the majority (n = 346) were published by first authors based in North America (58.25%) (see Table S1 in Electronic Supplementary Material [ESM]), of which 305 were located in the United States and Canada (n = 41).

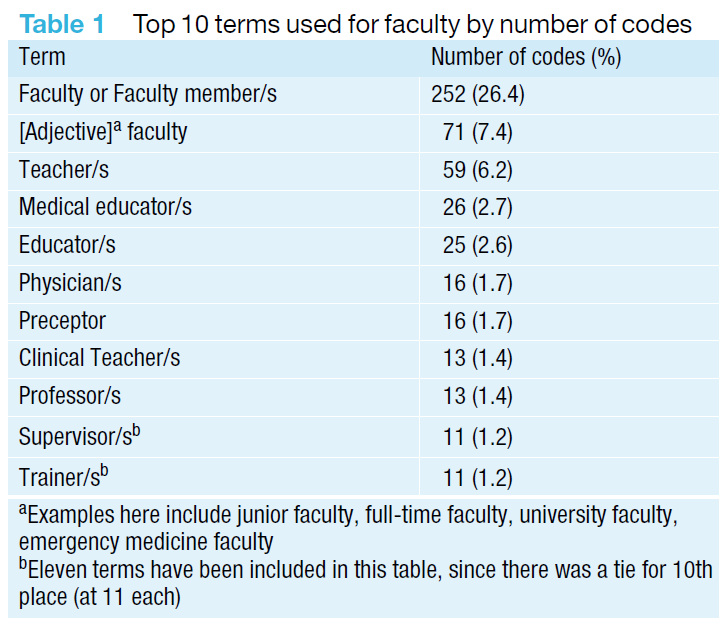

저자들은 279개의 독특한 용어를 사용하여 594개의 초록에서 총 954번 코딩된 "faculty"를 기술했다. 이 954명 중 가장 많이 사용되는 용어는 교수 또는 교수 구성원을 포함했다(n = 252; 26.4%). 표 1을 참조하십시오. 예를 들어, 한 연구는 "카라치의 의대생과 사립 및 공립 의대 교수진의 표절에 대한 지식과 인식을 평가하기 위한 것"으로 그 목적을 설명했다. 또한 교수진 또는 교수진/s는 71번 코딩되었다(예: [임상] 교수진). 교수진(교직원 포함)과 교수진(교직원 포함)은 전체 코드의 33.8%를 차지한다. 교사/s(n = 59; 6.2%)와 의료 교육자/s(n = 26; 2.7%)에 대한 코드가 잘 표현되어 모든 코드의 거의 10%를 차지했다.

Authors described “faculty” using 279 unique terms coded a total of 954 times in the 594 abstracts. Of these 954, the most frequently used terms included faculty or faculty member/s (n = 252; 26.4%); see Tab. 1. For example, one study described its purpose as: “To assess knowledge and perceptions of plagiarism in medical students and faculty of private and public medical colleges in Karachi” [7, underlining added]. Additionally, [adjective] faculty or faculty member/s was coded 71 times (e.g., [clinical] faculty). Together, faculty (including faculty member/s) and [adjective] faculty (including faculty member/s) accounted for 33.8% of all codes. Codes for teacher/s (n = 59; 6.2%) and medical educator/s (n = 26; 2.7%) were well represented, accounting for almost 10% of all codes.

전체 표본과 유사하게, 우리는 [지리적 영역]에 걸쳐 저자들이 사용한 용어의 일정 수준 변화를 관찰했다(ESM의 부록 참조). 예를 들어, 유럽과 중앙아시아, 중남미, 카리브해에서 사용되는 최고 용어는 "교사"였다. 특히 사하라 이남 아프리카에서는 10개의 용어가 모두 한 번씩 추상적으로 코딩되어 상위 용어를 결정할 수 없었습니다.

Similar to the overall sample, we observed some level of variation in the terms used by authors across geographical regions (see Appendix in ESM). For example, the top term used in Europe & Central Asia and Latin America and the Caribbean was “teachers”, whereas, in all other regions, the top term was faculty/faculty members. Notably, we could not determine top terms in sub-Saharan Africa as all ten terms were coded once in abstracts from that region.

44%의 초록은 한 개 이상의 용어를 사용하는 연구 집단을 언급했습니다. 예를 들어, 한 초록은 참가자들의 교수와 학습 개념을 이해하기 위한 연구를 묘사하고 참가자들을 "의료 교사", "교사", "교직원"으로 분류했다. 평균적으로 각 초록에는 1.74개의 단어로 코딩되었으며, 단일 초록에는 1~6개의 단어로 구성되었다. 특히, 우리는 같은 주제에 관한 출판물에서도 저자들이 교수 모집단을 설명하기 위해 다른 용어를 사용했다는 것을 관찰했다. 예를 들어 전문직업성에 초점을 맞춘 세 가지 초록에서 의료 교사[8], 의사[9], 교수진[10]의 사용을 관찰했다.

Forty-four percent of abstracts referred to the study population using more than one term. For example, one abstract described a study to understand participants’ conceptions of teaching and learning and labeled the participants as “medical teachers”, “teachers”, and “faculty”. On average, each abstract was coded with 1.74 terms related to faculty with a range of 1–6 terms for any single abstract. Notably, we observed that even in publications on the same topic, authors used different terms to describe faculty populations. For example, in three abstracts focused on professionalism we observed the use of: medical teachers [8], physicians [9], and faculty [10].

우리는 초록과 식별된 용어에 대한 내용 분석을 바탕으로 저자들이 역할 유형에 따라 교수진을 언급하는 것을 관찰했습니다. 우리는 네 가지 역할을 식별했다

- 건강관리에서의 역할(예: 의사, 의사),

- 교육에서의 역할(예: 교육자, 교사),

- 학계에서의 역할(예: 교수, 교수) 또는

- 학습자와의 관계에서의 역할(예: 멘토, 감독자).

ESM의 S2 및 추출된 모든 용어 목록은 ESM의 부록을 참조하십시오.

Based on our content analysis of the abstracts and identified terms, we observed that authors referred to faculty based on role types. We identified four types of roles: roles in healthcare (e.g., doctor, physician), roles in education (e.g., educator, teacher), roles in academia (e.g., faculty member, professor), or roles in relationship to the learner (e.g., mentor, supervisor); see Fig. S2 in ESM and, for a list of all terms extracted, see the Appendix in ESM.

교직원을 설명하기 위해 여러 용어를 사용하는 것 외에도, 하나의 추상화에서 역할 범주를 가로지르는 용어가 포함된 사례를 확인했습니다. 예를 들어, 어떤 초록은 다음과 같이 읽힌다. "… 독일 괴팅겐 의과대학의 의학 교수에 관련된 의사들이 임상 교사의 교육 능력에 대한 그들의 견해를 다루는 온라인 설문조사를 완료하도록 초대되었다. 또한 교육학적 교육에 참여하려는 의사의 동기가 평가되었다. [11, 밑줄 추가]. 이 예제는 의료와 교육 모두에서 참여자의 역할을 설명하는 용어를 사용하여 학습자에게 지식이나 기술을 전달하는 동일한 그룹의 개인의 이름을 지정합니다.

In addition to using multiple terms to describe faculty, we identified instances in which a single abstract included terms that cut across our role categories. For example, one abstract reads as follows: “… physicians involved in medical teaching at Göttingen Medical School, Germany, were invited to complete an online survey addressing their views on clinical teachers’ educational skills. In addition, physicians’ motivation to engage in pedagogical training was assessed” [11, underlining added]. This example uses terms that describe participants’ roles in both health care and education to name the same group of individuals imparting knowledge or skills to learners.

논의

Discussion

우리는 "다른 사람이나 그룹의 발전에 영향을 주기 위한 어떤 종류의 활동에 참여하는 사람 또는 집단"을 설명하는 데 사용되는 279개의 고유한 용어를 식별했다. 이들은 교수진부터 교사, 트레이너까지 다양했다. 우리는 다양한 용어의 사용이 역할 유형과 관련된 네 가지 범주 중 하나에 매핑될 수 있다는 것에 고무되었다: 의료 역할, 교육 역할, 학계에서의 역할 또는 학습자와의 관계. 우리는 또한 동일한 연구에서 동일한 그룹을 설명할 때 많은 초록들이 둘 이상의 용어 또는 둘 이상의 역할에 대한 참조를 사용한다는 것을 관찰했다.

We identified 279 unique terms used to describe a person or group of people who engage in some sort of activity intended to impact another person or group’s development. These ranged from faculty to teacher to trainer. We were encouraged that the varied use of terms could be mapped to one of four categories related to role type: role in healthcare, role in education, role in academia, or relationship to learner. We also observed that many abstracts used more than one term, or reference to more than one role, when describing the same group in the same study.

우리가 관찰한 높은 수준의 변동은 특정 주제와 관련된 정의적 명확성에 초점을 맞춘 관련 연구의 발견과 일치한다[2, 3]. 예를 들어 CBME의 정의를 연구하는 연구자들은 80개 논문의 표본에서 19개의 정의를 식별했다[2]. 우리의 연구 결과는 또한 HPE scholarship의 역할과 조직 구조를 설명하는 다양한 용어의 문제에 직면한 Varpio와 동료들의 연구와 일치한다[12]. 우리는 가장 자주 사용되는 용어와 관련하여 전 세계 지역 간의 유사성을 보았지만, 우리는 이러한 용어들이 이러한 국가들에서 다른 것을 의미하기 위해 사용될 수 있다는 것을 받아들여야 한다.

The high level of variation we observed aligns with findings of related studies focused on definitional clarity related to specific topics [2, 3]. For example, researchers studying definitions of competency-based medical education identified 19 definitions in a sample of 80 articles [2]. Our findings also align with research by Varpio and colleagues, who encountered a problem of differing terminologies describing HPE scholarship roles and organizational structures [12]. We observed cultural variation in terms used, though we saw similarities across world regions regarding terms used most frequently; one must accept that these terms could be used to mean different things in these countries.

영어가 모국어가 아닌 일부 국가에서는 "faculty"라는 용어가 동일한 개념을 설명하기 위해 다른 방식으로 사용된다. 예를 들어 일본에서는 '시도이'와 '교인'이라는 단어가 'faculty'과 비슷한 의미로 쓰이지만 문화적인 차이로 인해 의미가 다르다. 'faculty'의 정의에 대한 국제 공동 연구가 더 발전하려면 세계 각지에서 동일한 개념을 설명하기 위해 다른 단어를 사용하는지 조사할 필요가 있다.

In some countries where English is not the native language, the term “faculty” is used in a different way to describe the same concept. In Japan, for example, the words “Shidoi” and “Kyoin” are used in a similar sense to “faculty”, but they have different meanings due to cultural differences. If international joint research on the definition of “faculty” is to be further developed, it is necessary to investigate the use of different words to describe the same concept across world regions.

의학 교육의 이론 구축 및 협력에 대한 시사점

Implications for theory building and collaboration in medical education

의사소통에 영향을 미치는 오해는 [문화간 협력 상황에서 관련 개념과 용어에 대한 공유된 이해가 부족하기 때문]일 수 있다[13]. 연구자와 교육자가 다양한 방식으로 용어를 사용할 경우, 이는 오해를 불러일으키고 현장에 대한 진행과 독자/연구자의 참여를 방해한다. 따라서 명확한 용어가 부족하기 때문에 기존 연구를 기반으로 하는 것이 어려워집니다. 이것은 국제 협력을 위협합니다. 국제 연구팀과 HPE를 발전시켜 공동으로 이론을 세울 수 있도록 하려면 다양한 맥락에서 서로 다른 용어가 어떻게 다른 의미를 가질 수 있는지를 이해하는 방법을 찾는 것이 중요하다. 이를 위해 저자는 [협업을 촉진]하고, [HPE 연구자들이 보유한 많은 학문적 전통에서 발생하는 문제를 완화]하기 위해 이론, 추론 및 가치를 더 잘 표현해야 한다[14]. 또한 이론적 프레임워크는 연구에 점점 더 많이 통합되어야 하며, 우리는 더 이전 연구를 기반으로 해야 한다[15]. 이것은 정의적인 명확성 없이는 하기 어렵지만, 한 분야로서 우리는 발전하고 있다. 예를 들어, 학자들은 최근 어떻게 사회 학습 이론이 보건 직업 교육에서 지식을 진보시키고 더 나아가 실천을 안내하기 위한 출발점으로 사용되고 있는지 탐구했다[16]. 이 연구를 통해 우리도 언어를 통한 지식 증진, 실천 지도, 협업 촉진에 대한 이러한 생각들에 기여하고 있습니다. 과정과 결과뿐만 아니라 HPE 연구 내 그룹도 기술하는 공유 언어가 필요합니다.

Misunderstandings affecting communication could be due to a lack of a shared understanding on related concepts and terminology in intercultural collaboration settings [13]. When researchers and educators use terms in varied ways, this potentiates misunderstanding and hampers progress and reader/researcher engagement in the field. Thus, it becomes difficult to build on existing research due to a lack of clear terminology. This threatens international collaborations. If we want to advance HPE with international research teams and enable them to jointly build theory, it is critical that we find ways of understanding how different terms may mean different things in varied contexts. To achieve this, authors need to better articulate theories, reasoning and values to facilitate collaboration and mitigate issues arising from the many academic traditions held by HPE researchers [14]. Further, theoretical frameworks should be increasingly incorporated in research, and we should build more on previous research [15]. This is difficult to do without definitional clarity, but as a field we are making progress. For example, scholars have recently explored how social learning theory has been used as a starting point to advance knowledge and further guide practice in health professions education [16]. With this present study, we too contribute to these thoughts on advancing knowledge, guiding practice, and facilitating collaboration through language. A shared language describing not only processes and outcomes but also the groups within HPE research is necessary.

이론과 관련된 공유 이해를 위해 노력하듯이, teachers과 students를 표현할 때 사용하는 용어들이 글로벌한 이해를 촉진해야 서로의 작품을 정확하게 해석할 수 있다. 서로의 연구 결과를 토대로 관심 있는 현상에 대한 공통된 이해를 발전시키기 위해 종종 무시되는 전제조건은 [누가 유사한 현상을 연구했는지를 인식하는 것]이다. 우리는 이제 독자들에게 어떤 지역에서 통칭적으로 "faculty"로 알려진 사람들을 포함하는 연구 집단을 묘사할 수 있는 템플릿을 제공한다.

Just as we strive for shared understanding related to theories, the terms we use to describe our teachers and students must facilitate global understanding, so we can accurately interpret each other’s work. An often-neglected prerequisite for building on each other’s research findings and developing a shared understanding of phenomena of interest to health professions education is recognizing who has studied similar phenomena. We now offer readers a template to describe a research population that includes people colloquially known as “faculty” in some regions.

템플릿 제안

Template proposal

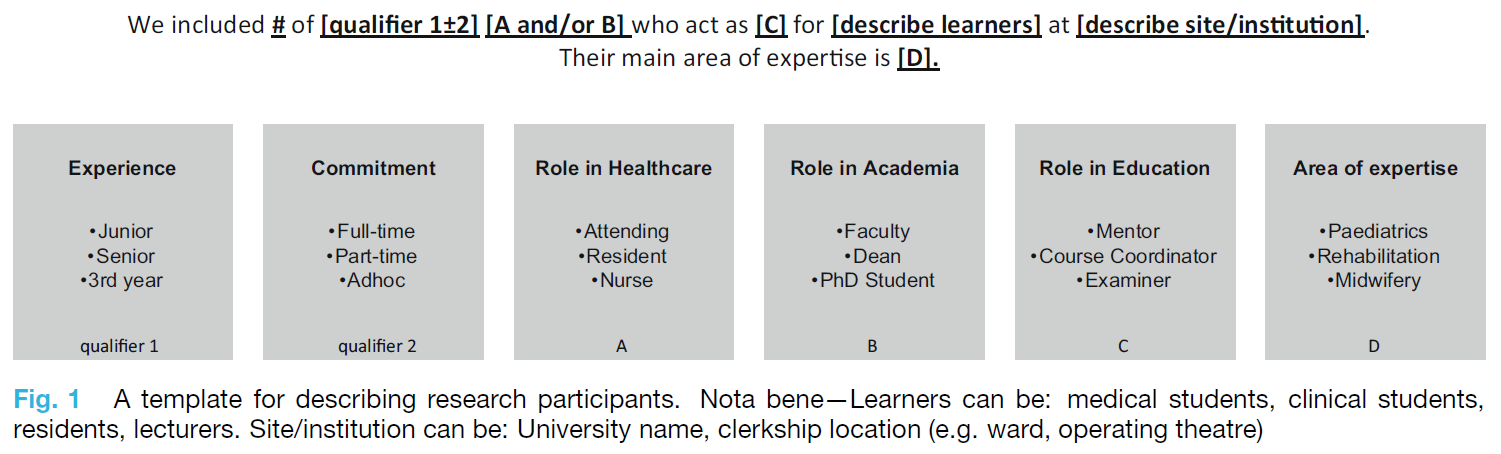

의학 교육은 다양한 학문적 전통을 따르는 연구자들과 함께 "용광 냄비"로 묘사되어 왔다. 이러한 "냄비"를 문화적, 지역적 변화에 더하면 진정한 공유는 어려울 수 있다. 따라서 HPE에서 교수진 또는 기타 모집단을 설명하는 공유 접근 방식에 더 가까이 다가가기 위해 연구원과 교육자가 faculty-관련 역할을 설명할 때 사용할 수 있는 템플릿(그림 1)을 제시한다. 이 템플릿은 연구 참가자를 설명하기 위해 용어를 사용하는 기존 관행을 유지하며, 이 용어를 더욱 적합하게 만든다(그림 1 참조). 논문 본문뿐만 아니라 초록에서도 연구 참여자들을 기술할 수 있는 구조가 마련되기를 기대한다. 또한, 우리는 이 명확한 설명이 향후 HPE에서 문헌의 협업과 해석에 도움이 될 수 있도록 제안한다. 우리는 연구 참여자가 누구인지, 그들의 역할은 무엇인지, 그리고 그들의 전문성 수준/영역을 명시하는 것이 개인의 해석에 중요하다고 믿는다. 그것은 또한 연구자들이 이전의 연구를 기반으로 하는 것을 용이하게 하여, 특정 분야의 지식의 본체를 성장시킬 것이다. 구어적으로 "faculty"으로 알려진 사람들을 묘사하기 위해 사용될 수 있는 모든 독특한 용어들의 단일 정의는 어려울 것이다. 대신 혼란을 최소화하기 위해 연구 참가자에 대한 명시적인 설명을 제안한다.

Medical education has been described as a “melting pot”, with researchers hailing from a variety of academic traditions [14]. Adding this “pot” to cultural and regional variation, true shared understanding may be difficult. Thus, in an attempt to bring our field closer to a shared approach to describing faculty or other populations in HPE, we present a template (Fig. 1), which we propose researchers and educators can use when describing participants in a faculty-related role. This template maintains the existing practice we saw of using a term to describe research participants and another which further qualifies that term (see Fig. 1). We hope it will provide a structure to describe research participants not only in the body of articles, but also in abstracts. Additionally, we propose this clear description could assist future collaboration and interpretation of literature in HPE. We believe being explicit about who research participants are, what their role is, and their level/area of expertise is crucial to individual interpretation. It will also facilitate researchers building on previous studies, thereby growing the body of knowledge in a particular field. Single definitions of every unique term that can be used to describe those who are colloquially known as “faculty” will be difficult. Instead, we suggest explicit descriptions of research participants to minimize confusion.

이 템플릿(그림 1)에 기초하여, 논문의 메소드 섹션에 있는 완성된 예는 다음과 같다.

Based on this template (Fig. 1), a completed example in the methods section of a paper might read as follows:

우리는 서인도 대학 의대 3학년 학생들의 과정 코디네이터로 활동하는 711명의 전임 의사들을 포함했다. 이 의사들은 소아과, 수술, 그리고 의학을 포함한 다양한 전문분야에서 왔다.

We included 711 full-time physicians who act as course coordinators for third year medical students at The University of The West Indies. These physicians are from varied specialties including paediatrics, surgery, and medicine.

전체 템플릿을 사용하는 것이 항상 가능하거나 실용적이지는 않을 수 있으며 특정 요구에 맞게 조정할 수 있습니다. 예를 들어, 초록에서는 예제의 첫 번째 문장만 사용하고 메소드 섹션에 대한 자세한 내용을 남길 수 있습니다. 연구 참여자들은 또한 연구 질문의 보고에 종종 묘사된다. 템플릿을 사용하여 연구 질문을 다음과 같이 설명할 수 있다: "따라서, 본 연구는 다음과 같은 연구 질문에 답하는 것을 목표로 했다. 주니어 임상의 교육자들은 침상에서 가르치는 데 있어 자신의 역할을 어떻게 보고 있습니까?" 이 예에서 알 수 있듯이, 제안된 템플릿은 연구 참여자들이 건강 관리에 대한 역할, 교육에서의 역할, 학계에서의 역할, 학습자와의 관계와 관련된 정보를 명확하게 보고하는 것을 목표로 한다.

Using the full template may not always be possible or practical, and it can be adapted for specific needs. For instance, in an abstract, one might use only the first sentence from the example and leave further details for the methods section. Research participants are also often described in the reporting of research questions. Using the template, a research question could be described as follows: “Thus, this study aimed to answer the following research question: How do junior clinician educators view their roles in teaching at the bedside?” As this example shows, the suggested template aims to clearly report information related to the research participants’ role in healthcare, their role in education, their role in academia, and their relationship to learners.

장점 및 한계

Strengths and limitations

우리의 접근 방식에서, 우리는 미국 국립 의학 도서관이 MeSH "faculty"로 기사를 색인화한 방법을 기반으로 체계적으로 초록을 식별했다. 우리는 미국에 기반을 둔 인덱서가 자신의 작업에 의도치 않게 문화적 편견을 도입했을 수 있다는 것을 인지한다. 우리의 코딩에서, 우리는 106개의 추상들을 "null" 또는 교수진과 관련된 용어가 없는 것으로 확인했습니다. 따라서 인덱싱에 불일치가 있을 수 있습니다. 우리의 샘플을 모으기 위해, 우리는 그것이 자유롭게 이용할 수 있는 자원이기 때문에 일부러 PubMed를 선택했습니다. 그러나 모든 의학 교육 저널을 포함하는 것은 아니며 따라서 특정 국가 또는 지역에서 영향력이 있을 수 있는 저널을 포함하는 것은 PubMed만의 문제가 아니다.

In our approach, we systematically identified abstracts based on how the United States (US) National Library of Medicine indexed articles with the MeSH “faculty”. We recognize that the US-based indexers may have inadvertently introduced their own cultural biases into their work. In our coding, we identified 106 abstracts as “null” or without terminology related to faculty. Taken together, this suggests that there may be some inconsistencies in indexing. To gather our sample, we purposely chose PubMed as it is a freely available resource. However, it does not include coverage of all medical education journals and thus of journals that might be influential in specific countries or regions, an issue not unique to PubMed.

우리가 영어로 된 출판물(일부)만 사용했기 때문에, 우리는 비영어 배경의 작가들이 모국어 개념을 영어로 번역해야 했다는 것을 인정해야 한다. 이것은 종종 단순한 번역 그 이상이며, trans- 또는 심지어 deculturation과 관련될 수 있다. 그럴 경우 우리의 콘텐츠 분석에는 불완전한 도메인과 예가 포함될 수 있지만, 이는 단 하나의 단어보다는 연구 참가자들의 설명에 템플릿을 사용하자는 우리의 제안을 더 강화해줄 것이다.

As we used only (parts of) publications in English, we have to acknowledge that authors from non-English backgrounds had to translate their native language concepts into English. This is often more than merely a translation and may involve a trans- or even deculturation. In that case, our content analysis may contain incomplete domains and examples, but it reinforces our plea to use a template for the description of research participants rather than a single word.

나아가 비영어권 국가의 의학교육 문헌에서 얼마나 많은 논문이 '교양'과 유사한 단어를 사용하고 있는지, 또 어떤 용어가 사용되는지, 영어에서 포착되지 않은 의미를 어떻게 더할 수 있는지 파악할 수 없었다. 비영어권 국가의 교수진과 관련된 용어에 초점을 맞춘 연구는 국제 공동 연구의 일환으로 향후 수행될 필요가 있다.

Furthermore, we were unable to determine how many papers in medical education literature in non-English speaking countries use words similar to “faculty”, what other terms are used, and how they may add meanings that are not captured in English. Research focusing on terms related to faculty in non-English speaking countries needs to be carried out in the future as part of international joint research.

결론

Conclusion

우리는 HPE를 다루는 것을 포함하여 생물의학 문헌에서 거의 600개의 초록에서 교수 관련 용어의 다양한 사용을 식별하고 설명했다. 우리는 이 용어를 네 가지 주요 교수 역할에 매핑하고 연구 참가자를 설명할 때 사용할 수 있는 템플릿을 제공하기 위해 사용했다. 이것은 HPE에서 일반적으로 사용되는 용어에 대한 공통된 이해를 향한 단계이다. HPE 내의 다른 용어의 변동 정도를 조사하고 템플릿을 사용하고 테스트하기 위해 다른 연구자들이 우리의 방법론을 채택하도록 초대한다.

We identified and described the varying use of faculty-related terms in almost 600 abstracts from biomedical literature, including that covering HPE. We mapped the terms to four key faculty roles and used them to offer researchers a template for use when describing research participants. This is a step toward shared understanding of commonly used terms in HPE. We invite other researchers to adopt our methodology to investigate the extent of variation in other terms within HPE, and to use and test our template.

Perspect Med Educ. 2022 Jan;11(1):22-27.

doi: 10.1007/s40037-021-00683-8. Epub 2021 Sep 10.

Advancing the science of health professions education through a shared understanding of terminology: a content analysis of terms for "faculty"

PMID: 34506010

PMCID: PMC8733114

DOI: 10.1007/s40037-021-00683-8

Free PMC articleAbstract

Introduction: Health professions educators risk misunderstandings where terms and concepts are not clearly defined, hampering the field's progress. This risk is especially pronounced with ambiguity in describing roles. This study explores the variety of terms used by researchers and educators to describe "faculty", with the aim to facilitate definitional clarity, and create a shared terminology and approach to describing this term.

Methods: The authors analyzed journal article abstracts to identify the specific words and phrases used to describe individuals or groups of people referred to as faculty. To identify abstracts, PubMed articles indexed with the Medical Subject Heading "faculty" published between 2007 and 2017 were retrieved. Authors iteratively extracted data and used content analysis to identify patterns and themes.

Results: A total of 5,436 citations were retrieved, of which 3,354 were deemed eligible. Based on a sample of 594 abstracts (17.7%), we found 279 unique terms. The most commonly used terms accounted for approximately one-third of the sample and included faculty or faculty member/s (n = 252; 26.4%); teacher/s (n = 59; 6.2%) and medical educator/s (n = 26; 2.7%) were also well represented. Content analysis highlighted that the different descriptors authors used referred to four role types: healthcare (e.g., doctor, physician), education (e.g., educator, teacher), academia (e.g., professor), and/or relationship to the learner (e.g., mentor).

Discussion: Faculty are described using a wide variety of terms, which can be linked to four role descriptions. The authors propose a template for researchers and educators who want to refer to faculty in their papers. This is important to advance the field and increase readers' assessment of transferability.

Keywords: Content analysis; Faculty terminology; Literature study.

© 2021. The Author(s).