무엇이 곁에 선 안내자가 되게 만들어주는가? 보건의료전문직 교육에서 멘토들의 동기 및 접근법에 대한 질적 연구(Med Teach, 2022)

What sparks a guide on the side? A qualitative study to explore motivations and approaches of mentors in health professions education

Subha Ramani, Rashmi A. Kusurkar, Evangelos Papageorgiou & Susan van Schalkwyk

소개

Introduction

멘토링은 다양한 직업에서 직업 개발, 직업 정체성 형성, 직업 만족에 대한 가치 있는 접근법으로 널리 받아들여진다. 2004; Berk 등. 2005; Sambunjak 등. 2006; Taylor 등. 2009; Driessen 등. 2011; Polololi 등. 2015; Choi 등. 2019). 보건 직업 교육(HPE)의 맥락에서 멘토쉽은 멘토 보유의 중요성, 학부 및 대학원 수준의 멘토쉽 특성, 성공적인 멘토-멘티 관계의 특성을 전경으로 하는 연구와 함께 잘 문서화되어 있다(Sambunjak 등. 2006; Driessen 등, 2011; Kashiwagi 등 20).13; Van Schalkwyk 등) 멘토링의 가치를 강조하고 교육자 포트폴리오에서 멘토링 역할의 중요성에 대한 인식을 높이는 연구(Simpson et al. 2007, 2013)에도 불구하고, 멘토가 이러한 역할을 맡는 이유에 대해서는 알려진 바가 거의 없다. 구체적으로, 왜 HPE의 리더들이 비공식적이고 국제적인 멘토링 역할을 자발적으로 받아들이는지 불분명하다. 이러한 지식은 가상 멘토링과 협업이 증가하는 이 시대에 가치가 있을 수 있습니다.

Mentoring is widely accepted as a valuable approach to professional development, professional identity formation, and career satisfaction in a variety of professions (Farrell et al. 2004; Berk et al. 2005; Sambunjak et al. 2006; Taylor et al. 2009; Driessen et al. 2011; Pololi et al. 2015; Choi et al. 2019). Mentorship in the context of health professions education (HPE) has been well-documented with studies foregrounding the importance of having a mentor, the nature of mentorship at both undergraduate and postgraduate level, and characteristics of successful mentor-mentee relationships (Sambunjak et al. 2006; Driessen et al. 2011; Kashiwagi et al. 2013; van Schalkwyk et al. 2017). Despite research emphasising the value of mentoring, and increasing recognition of the importance of mentoring roles in educators’ portfolios (Simpson et al. 2007, 2013), little is known about why mentors take on this role. Specifically, it is unclear why leaders in HPE voluntarily accept informal and international mentoring roles. This knowledge could be valuable in this era of increasing virtual mentoring and collaborations.

멘토링 역할을 맡은 이유는 멘토링 관계를 구축하는 방법에 영향을 미칠 수 있습니다. 그러나 HPE에 대한 연구는 멘토 관점에서 이러한 동기를 탐구한 연구는 거의 없다(Coates 2012). 앨런 외 연구진(1997)과 다른 이들은 멘토링의 동기가 외부 또는 타인-집중과 내부 또는 자기 집중으로 분류될 수 있다고 주장했다(Allen 외 1997; Beara 및 Hwangb 2015; Malota 2017). [타인-집중적인 동기]는 그 분야에 대한 지식을 다른 사람들에게 전달하고 돕고자 하는 열망을 특징으로 하는 반면, [자기 집중적인 동기]는 자신의 학습과 만족감을 증가시키고자 하는 열망을 나타낸다. 예를 들어, 중등학교 연구는 주니어 교사들이 멘티들 사이에서 더 나은 선생님들을 발전시키는 데 도움이 될 뿐만 아니라 멘토들을 위한 리더십의 디딤돌로 작용한다고 보고한다(Little 1990). 비즈니스 문헌에 따르면 좋은 멘토링의 수혜자였던 임원들은 다른 사람들을 멘토링할 의사가 더 많으며(Allen 등 1997), 멘토링 역할을 네트워킹, 승진 또는 유산을 남기는 기회로 보는 경우가 많다(Aryee 등 1996). 비록 모든 멘토링 관계가 자신과 다른 집중의 결합일 가능성이 있지만, 지배적인 초점은 멘토링 관계가 어떻게 구성되는지에 영향을 미칠 수 있다.

Mentors’ reasons for taking on mentoring roles could influence how they construct their mentoring relationships (Wang et al. 2009; van Ginkel et al. 2016), but few studies in HPE have explored these motivations from the mentors’ perspective (Coates 2012). Allen et al. (1997) and others have argued that motives for mentoring could be classified as outward or other-focussed and inward or self-focussed (Allen et al. 1997; Beara and Hwangb 2015; Malota 2017). Other-focussed motives feature a desire to help and pass on knowledge about the field to others, while self-focussed motives indicate a desire to increase own learning and sense of gratification. Drawing upon research from other fields, for example, secondary school studies report that mentoring junior teachers not only helps develop better teachers among mentees, but also serves as a stepping stone to leadership for the mentors (Little 1990). Business literature indicates that executives who have been the beneficiaries of good mentoring are more willing to mentor others (Allen et al. 1997), and many view mentoring roles as opportunities to network, advance in their career or leave a legacy (Aryee et al. 1996). Although all mentoring relationships are likely to be a combination of self and other focussed, the focus that is dominant could influence how mentoring relationships are constructed.

멘토-멘티 관계는 멘토링의 핵심이며, 할당받지 않은, 비공식적인, (자신의) 선택을 통해 만들어진 관계가, 기관에서 공식적으로 지정한 관계보다, 직업적 만족도를 높이는 데 더 성공적일 수 있다고 주장되어 왔다(Jackson 등 2003; Dobie 등 2010). 멘토-멘티 교육자 디아드의 경우, 이상적인 관계는 멘티의 변화하는 요구에 상호적이고, 상호 유익하며, 반응해야 한다(Dobie et al. 2010). Losveld 등은 최근 멘토 관계에서 멘토들이 가지고 있는 네 가지 주요 포지션을 설명했다: 촉진자, 코치, 모니터, 그리고 모범; 저자들은 이러한 포지션을 그들의 믿음을 연습에 적용하는 방법과 연결시켰다(Loosveld 등 2020).

Mentor-mentee relationships are at the core of mentoring and it has been argued that those that are unassigned, develop informally and through choice may be more successful in enhancing professional satisfaction than those formally assigned by institutions (Jackson et al. 2003; Dobie et al. 2010). For mentor-mentee educator dyads, the ideal relationship should be reciprocal, mutually beneficial, and responsive to the mentee’s changing needs (Dobie et al. 2010). Loosveld et al. recently described four major positions held by mentors in their mentoring relationships: the facilitator, coach, monitor, and exemplar; the authors linked these positions to how they apply their beliefs to practice (Loosveld et al. 2020).

기술의 발전은 지리적 경계에 구애받지 않는 관계를 촉진했다(그리피스 및 밀러 2005). E-멘토링은 "시간과 공간의 한계를 확장하고 평등한 역학을 만들어내"며, 멘티의 특정 요구에 맞춘 경우 혁신적인 전문적 개발을 제공할 수 있는 잠재력이 있다. 따라서 본 연구에서는 멘토들이 지리적 경계를 넘어 자발적으로 멘토링 역할을 수행하도록 동기 부여가 무엇인지, 그리고 이러한 동기가 멘토링의 선택에 어떤 영향을 미치는지 이해함으로써 이 분야의 작업을 진전시키는 것을 목표로 했다.

Advances in technology have facilitated professional relationships unconstrained by geographical boundaries (Griffiths and Miller 2005). E-mentoring “extends the limitations of time and space and creates egalitarian dynamics” (Schichtel 2009, 2010) with the potential to provide transformative professional development if tailored to mentees’ specific needs (Dorner et al. 2021). In this study, therefore, we aimed to take the work in this area forward by seeking to understand what motivates mentors to volunteer to take on a mentoring role across geographical boundaries, and how this motivation influences the choice of strategies they bring to bear on it.

- 어떤 요소들이 보건 직업 교육의 고위 지도자들에게 그들의 기관 밖에서 더 많은 후배들과 교육자 지망생들을 멘토링하도록 동기를 부여합니까?

- 참가자들이 효과적인 멘토 관계를 육성하기 위해 일반적으로 채택하는 접근법은 무엇입니까?

- 글로벌 가상 멘토링에 대한 참가자들의 견해는 어떻습니까?

- What factors motivate senior leaders in health professions education to mentor more junior and aspiring educators outside their own institutions?

- What approaches do participants commonly adopt to nurture effective mentoring relationships?

- What are participants’ perspectives about global virtual mentoring?

방법들

Methods

비록 이 정성적인 연구는 내적, 외적으로 초점을 맞춘 멘토 동기와 접근법의 개념적 프레임워크에 의해 지도되었지만, 우리는 귀납적으로 작업했으며, 다양한 주제들의 발견에 개방적이었다. 우리의 이론적 입장은 [사회 구성주의의 상호 작용주의적 관점], 즉 멘토와 멘티 사이의 경우 사회적 상호 작용을 통해 의미와 정체성이 생성되는 방법이었다(Mead et al. 2015).

Though this qualitative study was guided by the conceptual framework of inward and outward-focussed mentor motivations and approaches, we worked inductively and remained open to discovery of a variety of themes. Our theoretical stance was an interactionist perspective of social constructionism, i.e. how meaning and identity are generated through social interactions, in this case between a mentor and mentee (Mead et al. 2015).

스터디 설정

Study setting

유럽 의료 교육 협회(AMEE)는 보건 직업 교육자들을 위한 가장 큰 국제 기구 중 하나이다. 멘토링을 명시적인 우선순위로 강조하기 위해, AMEE는 2019년 연례 회의에서 제도적, 지리적 경계를 넘어 멘토링 이니셔티브를 구현했다. 멘토나 멘티로 참여하는데 관심이 있는 사람들은 그들의 위치, 직업적 역할, 전문성, 관심사에 대한 간단한 설문조사를 완료하도록 요청받았다. 멘토는 AMEE 내 펠로우십 성과나 학력 및 현장 참여도 측면에서 공식적인 국제적 인정을 바탕으로 선발됐다. 36명의 멘토-멘티 쌍을 매칭하고, 서로의 이메일과 함께 제공하며, 그들 자신을 소개하고, 그들의 관계에 대한 목표에 대해 논의하고, 그들의 적합성을 확인하고, 온라인 및 직접 미팅 일정을 잡기 위해 더 많은 의사소통을 요청했습니다. 매칭은 글로벌 멘토 풀의 다양성을 활용했습니다. 모든 멘티가 다른 나라에 위치한 멘토와 짝을 이뤄 컨퍼런스에서 직접 만났더라도, 원거리 관계가 필요했다. 이 이니셔티브에 참여하는 것은 전적으로 자발적이었으며 참여하지 않는 것은 조직 내에서의 그들의 지위에 영향을 미치지 않았을 것이다.

The Association for Medical Education in Europe (AMEE) is one of the largest international organisations serving health professions educators (www.amee.org). To highlight mentoring as an explicit priority, AMEE implemented a mentoring initiative across institutional and geographical boundaries at the 2019 annual meeting. Those interested in participating as a mentor or mentee were asked to complete a short survey about their location, professional roles, expertise and interests. Mentors were selected based on achievement of fellowship within AMEE or formal international recognition in terms of scholarship and engagement in the field. Thirty-six mentor-mentee pairs were matched, provided with each other’s emails and asked to communicate further to introduce themselves, discuss goals for their relationship, ascertain their fit, and schedule online and in-person meetings. The matching capitalised on the diversity of the global mentor pool. All mentees were paired with mentors located in a different country, thus requiring a distance relationship even if they met in person at the conference. Participating in this initiative was completely voluntary and non-participation would not have affected their standing in the organisation.

샘플링 및 모집

Sampling and recruitment

36명의 멘토들이 AMEE 멘토링 이니셔티브에 참여했습니다. 이번 멘토링 이니셔티브를 위해 참가자들은 건강직업 교육에 대한 직업적 관심이 있는 멘티들의 멘토로 봉사활동을 펼쳤었다. 이 중 10명의 멘토들이 Zoom을 통해 일대일 인터뷰에 참여하도록 초청되었다. 최종 선정은 지리적 다양성과 충족가능성에 기초했다. 연구팀은 참가자들의 멘토링에 대한 동기와 접근방식을 탐구하기 위해 연구 목적과 위에서 설명한 문헌에 의해 알려진 개방형 질문을 개발했다. 동시 데이터 수집 및 분석을 통해 향후 인터뷰를 위한 트리거 질문의 수정 사항을 알 수 있습니다.

Thirty six mentors participated in the AMEE mentoring initiative. For this mentoring initiative, participants had volunteered to serve as mentors for mentees with a career interest in health professions education. Ten of these mentors were invited to participate in one-on-one interviews via Zoom. Final selection was based on geographical diversity and availability to meet. The research team developed open-ended questions, informed by the research aim and literature described above, to explore participants’ motivations and approaches to mentoring. Concurrent data collection and analysis informed revisions to the trigger questions for future interviews.

예시 트리거 질문은 보충 부록 1에 포함되어 있습니다. 참가자가 대화 중에 자발적으로 이러한 부분을 제기했는지에 대해 모든 질문이 제기되지는 않았다. "더 자세히 말해줘", "확장해줄 수 있어" 등과 같은 프롬프트와 프로브가 필요에 따라 사용되었습니다.

Sample trigger questions are included in Supplementary Appendix 1. Not all questions were posed if the participant spontaneously raised these areas during the conversation. Prompts and probes were used as needed such as “tell me more,” “can you expand on that” etc.

3명의 조사관(SR, RAK, EP)이 10명의 인터뷰를 모두 진행했다. 인터뷰는 50-60분 동안 진행되었고, 오디오 테이프로 녹음되었으며, 참가자들의 동의 하에 녹음되었다. 비록 우리가 10번의 인터뷰를 바탕으로 주제포화를 주장할 수는 없지만, 연구팀은 우리가 우리의 연구문제를 해결하기에 충분한 데이터를 생성했다고 믿는다.

Three investigators (SR, RAK, EP) conducted all ten interviews. Interviews lasted 50–60 min, were audiotaped, and transcribed with consent of participants. Though we cannot claim thematic saturation based on 10 interviews, the research team believed that we generated sufficient data to address our study questions.

데이터 분석

Data analysis

모든 데이터는 분석 전에 식별되지 않아 내러티브가 개인으로 거슬러 올라갈 수 없었다. 주제 분석을 사용하여 연구자가 데이터를 검토하여 주제, 관계 및 의미 패턴을 식별했다(Kiger 및 Varpio 2020). 주제 분석은 여러 단계로 구성된다:

- 데이터의 톤과 내용에 익숙해지기;

- 특정 개념에 관련된 데이터 세그먼트 코딩 또는 라벨링하기;

- 코드, 코딩 범주, 코드 간의 관계를 포함한 해석으로 주제 생성;

- 연구 팀 내 주제 토론;

- 주제 마무리;

- 자료 발표.

All data were de-identified prior to analysis so that narratives could not be traced back to individuals. We used thematic analysis, where the researcher examines the data to identify themes, relationships, and patterns of meaning (Kiger and Varpio 2020). Thematic analysis comprises several steps:

- familiarisation with tone and content of the data;

- coding or labelling data segments pertaining to a specific concept;

- generation of themes involving interpretation of codes, coding categories and their relationship with each other;

- discussion of themes within the research team;

- finalising themes; and

- presentation of data.

위에서 언급한 바와 같이, 분석에 대한 우리의 접근법은 귀납적, 즉 선험적 가설이 없는 테마의 데이터 유도 식별(Varpio 등 2020; Young 등 2020)이었다. 각 사본은 두 명의 조사자(SR, RAK)에 의해 독립적으로 코딩되었고 두 명의 추가 조사자가 코딩 체계coding scheme를 마무리하는 데 참여했다. 코딩 및 테마 생성에 대한 모호성이나 불일치는 연구팀 회의에서 합의를 통해 해결되었다.

As mentioned above, our approach to analysis was inductive, i.e. the data guided identification of themes without a priori hypotheses (Varpio et al. 2020; Young et al. 2020). Each transcript was independently coded by two investigators (SR, RAK) and two additional investigators were involved in finalising the coding scheme (SCVS, EP). Any ambiguities or disagreements in coding and generation of themes were resolved by consensus during research team meetings.

반사율

Reflexivity

연구 샘플링, 데이터 수집, 데이터 해석 및 보고의 모든 단계 동안 반사성을 보장하기 위해 참여자뿐만 아니라 저자와 주제 사이의 관계를 성찰하는 것이 중요하다(Ramani et al. 2018). 저자 3명(SR, RAK, SCVS)은 각 기관에서 리더십 역할을 하는 HPE 연구원으로 정성적 연구 방법론 경험과 멘토링에 관심이 있다. SR과 RAK은 의학적 배경에서, SCVS는 사회과학 배경에서 왔다. 따라서, 그들은 다양한 관점, 이론적 입장, 그리고 서로의 가정과 편견에 의문을 제기하는 능력을 가져온다. 네 번째 저자(EP)는 교육 장학금과 멘토링 주제에 관심이 있는 주니어 의사이다. 저자들은 인터뷰 대상자를 많이 알고 있었지만 멘토 중 어느 한 명과 같은 기관에서 일하지도 않았고, 어떤 참가자에게도 권력의 위치에 있지도 않았다. 연구팀은 면접 후 보고회를 열고 면접관들이 개인의 편견, 가정, 의견이 참가자들의 반응을 방해하지 않도록 유의하고 있는지 확인하기 위해 각 성적표를 검토했다.

It is important to reflect on the relationship between the authors and the topic as well as participants to ensure reflexivity during all phases of the research- sampling, data collection, data interpretation and reporting (Ramani et al. 2018). Three authors (SR, RAK, SCVS) are HPE researchers with leadership roles at their respective institutions, with experience in qualitative research methodology and interest in mentoring. SR and RAK come from a medical background and SCVS from a social science background. Thus, they bring diverse perspectives, theoretical stances and the ability to question each other’s assumptions and biases. The fourth author (EP) is a junior doctor interested in educational scholarship and the topic of mentoring. Although the authors knew many of the interviewees, they did not work at the same institution as any of the mentors and were not in a position of power over any participant. The study team held post interview debriefings and examined each transcript to ensure that interviewers were mindful of not allowing personal biases, assumptions and opinions to interrupt participants' responses.

결과.

Results

줌을 통해 멘토 10명, 여성 5명, 남성 5명을 대상으로 개별 인터뷰를 진행했습니다. 이들 중 3명은 중견 교육자, 7명은 상급 교육자라고 밝혔다. 3명은 북아메리카, 1명은 카리브해, 2명은 유럽, 3명은 오스트랄라시아 출신이었다. 확인된 주제는 다음과 같이 분류되었다.

- (1) 왜: 멘토링의 이유

- (2) 어떻게: 멘토링 관계를 육성하는 방법

- (3) 무엇: 국제 및 가상 멘토링

We conducted individual interviews with ten mentors via Zoom, five female and five male participants. Three identified themselves as mid-career educators and seven as senior educators. Three were from North America, one from the Caribbean, two from Europe and three from Australasia. Themes identified were categorised as

- (1) Why- Motivations to mentor,

- (2) How- Approaches to foster mentoring relationships, and

- (3) What- Global and virtual mentoring.

We describe key themes under each category, along with representative quotes. The numbers P1, P2, etc. refer to the number assigned to each participant.

멘토에 대한 동기- 왜?

Motivations to mentor- Why?

멘티의 성장에 초점을 맞춘 육성 관계

Nurturing relationships focussed on mentees’ growth

참가자들은 멘토가 되기 위한 강한 의무imperative는 다른 사람들의 성공에 기여하고자 하는 열망이며 그들의 성공에 역할을 하는 것은 특권이라고 말했다. 멘티가 자신의 열정을 찾고 목표를 수립하며 목표를 이룰 계획을 수립하고 도전에 직면했을 때 포기하지 않도록 지도하고 지원하는 것이 이들의 근본적인 역할이었다. 이러한 맥락에서 [자신의 관심사와 경력 포부를 제쳐두고 다른 사람의 성공에 즐거움을 느끼는 것]으로 정의한 이타주의는 의미 있는 멘토링 관계에 매우 중요한 것으로 여겨졌다. 관계 형성은 타인을 돕고 이러한 경험에서 의미를 끌어내는 수단으로 여겨졌다. 모든 참가자들은 멘티가 이 관계의 중심에 있었고 그들의 목표가 우선이었다고 표현했는데, 예를 들어 "멘토는 그들이 누군가를 돕는다는 느낌(P1)으로부터 이익을 얻을지라도, 자신을 위한 것이 아니라 멘티를 위해 있다는 것을 명심해야 한다."고 했다. 마지막으로 멘티들이 잠재력을 발휘할 수 있도록 지원하고 그들이 수월성excellence에 도달하도록 도전시키는 것이 멘토링 관계의 만족스러운 측면이라고 언급되었다.

Participants stated that a strong imperative for being a mentor was the desire to contribute to the success of others and that playing a role in their success was a privilege. Their fundamental role was to guide and support mentees to find their passion, establish goals, formulate plans to achieve goals, and not give up when they encountered challenges. Altruism, a word used by one participant and defined in this context as setting aside their interests and career aspirations and taking pleasure in the success of others, was seen as critical to a meaningful mentoring relationship. Relationship building was viewed as the vehicle to helping others and deriving meaning from these experiences. All participants expressed that mentees were at the centre of this relationship and their goals were the priority, exemplified by this excerpt, “the mentor has to keep in mind that they are there for the mentee not for themselves, even though they will gain benefits from feeling that they're helping somebody (P1).” Finally, it was stated that supporting mentees in fulfilling their potential and challenging them to reach excellence were gratifying aspects of mentoring relationships.

저는 몇몇 멘티들의 성과에 뿌듯하고 감동받았습니다. 저는 그들의 관계에 감사를 느낍니다. 그들 중 일부를 지도할 수 있는 특권을요. 그것들은 나의 업적은 아니지만, 그들을 만나고 그들의 업적에서 어느 정도 작은 몫을 하게 되어 영광스럽게 생각합니다(P9).

I am proud and moved by some of my mentees’ accomplishments. I feel gratitude for their relationship, privileged to mentor some of them. They are not my accomplishments, but I feel honoured to have met them and to kind of share in some small way in their achievements (P9).

경험의 이익을 전하다.

Pass on the benefit of one’s experience

"뒤로 돌려주기Giving back"과 "앞으로 갚아나가기Paying forward"는 참가자들이 자주 사용하는 용어였다. 그들은 오랜 세월 동안, 그리고 어떤 경우에는 수십 년 동안 축적된 경험이 젊은 전문가들과 그들이 배운 것을 공유하는 데 도움이 되었다고 말했다. 멘토들은 그들의 직업적인 성공과 배운 교훈이 가치 있다고 느꼈습니다. 많은 멘토들이 자신의 직업적 한계와 오류로부터 상당히 많은 것을 배웠고, 이는 멘티들에게 풍부한 학습 경험이 될 것이라고 강조했다. 모두 자신이 좋은 멘토링의 수혜자임을 인식하고 멘토링의 전통을 이어가 멘티의 성공을 통해 그 분야가 지속적으로 성장할 수 있도록 열심이었다.

Giving back to the profession and paying forward were terms frequently used by participants. They stated that their accumulated experience across many years and in some cases over decades, helped them to share what they had learnt with the younger professionals. The mentors felt that their professional successes and lessons learned were valuable. Many emphasised that they had learned significantly from their own professional limitations and errors, and these would serve as a rich learning experience for mentees. All recognised that they had been recipients of good mentoring and were keen to carry on the tradition of mentoring so that the field could continue to grow through the successes of their mentees.

그것은 누군가의 커리어에 있어 구체적으로 도움이 될 수 있는 기회입니다. 저는 의학교육과 미래세대의 의학교육에 관심이 많습니다. 나는 훌륭한 멘토가 있었다. 그들은 멘토쉽에 대한 훌륭한 롤모델이었다. 그래서 저는 그들에게서 다른 사람들에게 전할 수 있는 많은 것을 배웠습니다.

It is an opportunity to be helpful to someone concretely in their career. I am very interested in medical education and nurturing future generations of medical educators… I had excellent mentors; they were excellent role models for mentorship. So I learned a lot from them that I could pass on to other people (P9).

자신의 지속적인 성장을 위해

For one’s own continued growth

모든 멘토들은 멘토링을 멘티로부터 많은 것을 배우는 양방향 관계로 묘사했습니다. 심지어 가장 나이가 많은 멘토들도, 멘티와의 참여로 많은 것을 배웠기 때문에, 모든 멘토 관계가 그들의 개인적 성장에 기여했다는 것을 인정했습니다. 또한, 그들은 특정 관계에서 발생하는 도전뿐만 아니라, 그 경험과 관계를 다루는 방식이 자기 성찰을 자극하고 직업적인 발전을 이루었다고 지적했다. 관계와 성장이 양방향이었다는 것을 모두가 인정했지만, 어떤 이들은 종종 이러한 경험의 결과로 그들이 얼마나 전문직으로서 계속 성장해 왔는지에 대해 놀라워했다.

All mentors described mentoring as a bidirectional relationship where they learned a lot from their mentees. Even the most senior mentors acknowledged that all mentoring relationships contributed to their personal growth, as they learned many things as a result of engagement with their mentees. Additionally, they indicated that the experience and how they handled the relationship, as well as the challenges that arose out of certain relationships, stimulated self-reflection and own professional development. While all acknowledged that the relationships and growth were bidirectional, some were often surprised at how much they continued to grow as professionals as a result of these experiences.

멘토와 멘티의 쌍방향 관계여야 합니다. 두 사람 모두 서로의 말을 경청하고 서로를 지도하고 배울 수 있어야 한다(P10).

It should be a two-way relationship between mentor and mentee. Both of them should be able to listen to each other and guide each other and learn from each other (P10).

나는 항상 많은 새로운 것을 배우는 것에 놀란다…멘토-멘티 관계… 너무 양방향인 것 같아요.

I’m always surprised to learn so many new things…mentor-mentee relationships… I think it's so bi-directional (P6).

멘토 관계를 조성하기 위한 접근 방식- 어떻게?

Approaches to foster mentoring relationships- How?

안전한 공간 제공

Provide a safe space

성공적인 멘토 관계를 위한 핵심 요소로서 안전과 신뢰가 강조되었다. '말하기 위해서는 안전하게 느껴야 한다. 이는 양측에 모두 정말 중요하다.' 멘티들이 토론을 주도하도록 독려하고, 멘토와 어떻게, 언제 연결할지, 결정하며 장점과 약점, 도전에 대한 자기반성을 편안하게 느끼는 전략 등이 제안됐다. 멘토들이 자신의 한계와 실수에 대한 이야기를 나눌 때 안전성도 강화됐다. 멘토-멘티 관계의 시작에서 어색함을 깨기 위해, 멘토들은 직업적으로 뿐만 아니라 개인적으로 서로를 알아가고, 원래 범위remit을 넘어 확장될 수 있는 종단적 관계를 형성할 것을 제안했다. 멘토와 멘티 사이의 신뢰는 심리적 안전의 풍토를 확립하는 데 필수적인 것으로 묘사되었다.

Safety and trust were emphasised as key elements for successful mentoring relationships “Feeling safe that one can talk. It's really important for both partners (P1).” Strategies proposed included encouraging mentees to take the lead in the discussions, deciding how and when to connect with mentors, feeling comfortable with self-reflection on strengths, weaknesses and challenges. Safety was also enhanced when mentors shared stories of their own limitations and mistakes. To break the ice at the start of a mentor-mentee relationship, mentors suggested getting to know each other in a personal as well as professional capacity and building trusting longitudinal relationships that may extend beyond their original remit. Trust between mentors and mentees was described as essential to establish a climate of psychological safety.

나는 멘토가 있었다…그는 나에게 직접적으로 조언을 해주지 않았다. 그는 항상 들으면서 말하곤 했어요, "당신은 무엇을 하고 싶나요?" 아니면 무엇이 옳다고 생각하나요?" 시간이 흐른 후 생각해보니, 기본적으로 내가 생각하는 바를 반영하기 위해 사람을 이용하고 있었다. 하지만 중요한 건 내가 믿었던 사람이어야만 했다는 것이다. 왜냐면 난 나 자신에 대한 잠재적인 약점들을 드러내고 있었거든. 저는 신뢰가 중요한 것이라고 생각합니다(P5).

I had a mentor…he never directly gave me advice. He would always listen and say, what do you want to do? Or what do you think is right? I worked out after a while that I was basically using a person to just reflect what I was thinking. But the important thing is it had to be somebody I trusted because I was revealing things that were potential weaknesses about myself. I think trust is an important thing (P5).

멘티와의 개인적 연결이 성공적인 멘토링 관계의 핵심 요소로 간주되었지만, 시간, 기대, 개인적 공간의 경계를 인식하는 것과 기밀 유지의 중요성도 강조되었다.

While a personal connection with mentees was viewed as a key element of successful mentoring relationships, awareness of boundaries of time, expectations, personal space, as well as the importance of maintaining confidentiality, were also emphasised.

관계에서 각자의 책임에 대한 명확한 기대와 책임에 대한 분명한 기대, 관계의 목표와 시간의 경계에 대한 명확한 기대(P9)를 갖는다고 생각합니다.

I think having clear expectations of the responsibilities of each person in the relationship and kind of a clear expectations of responsibilities and also of sort of the goals of the relationship and kind of the boundaries of time… the relationship (P9).

멘티가 자신의 전문적 개발에 대한 소유권을 가지도록 장려합니다.

Encourage mentees to take ownership of their professional development

모든 참가자들은 멘티들이 그 관계의 소유권ownership과 그들의 직업 목표를 가져야 한다고 강하게 강조했다. "우리는 어른들을 상대하고 있고, 그들은 새로운 아이디어를 가지고 갈 수 있다. 나는 항상 누군가의 손을 잡을 필요는 없다고 생각한다. 멘토가 도전을 성찰하고 지도하는 데 도움을 줄 수 있지만, (궁극적으로는) 멘티가 주도적으로 다음 단계를 수립하고, 그들의 계획을 따르고, 필요에 따라 멘토들과 다시 연결하도록 격려해야 한다고 느꼈습니다. 장점과 단점에 대한 자기 성찰을 촉진하는 것이 중요한 멘토 과제로 여겨졌다. 많은 멘토들이 교육 vs 초기 경력 vs 중간 경력에서 멘티들의 경력 단계에 맞춰 지도가 이루어져야 한다고 표현했다. 멘티가 대부분 초기 직업 교육자였던 이 특정 이니셔티브에 대해, 참여 멘토들은 멘티가 자신의 직업적 목표, 목표 달성을 위한 계획의 대략적인 아이디어를 가지고 준비해야 하며, 도전을 반성하고 미래 커뮤니케이션 일정을 계획할 준비가 되어 있어야 한다고 지적했다.

All participants strongly emphasised that mentees should assume ownership of the relationship and their career goals, “We are dealing with adults, …they can take some new ideas…and run with it. I don’t think there’s a need to hold somebody’s hand all the time (P1). While mentors could provide guidance and help reflect on challenges, it was felt that they should encourage the mentees to take the lead in formulating next steps, follow through with their plans and reconnect with mentors as needed. Facilitating self-reflection on strengths and weaknesses was considered an important mentor task. Many mentors expressed that guidance should be tailored to the mentees’ career stage, in training vs early career vs mid-career. For this particular initiative, where mentees were mostly early career educators, participating mentors indicated that the mentees should come prepared with a sense of their own professional goals, a rough idea of their plans to achieve goals, and be ready to reflect on challenges and take the initiative in scheduling future communications.

….멘티의 코트에 공을 넘겨야 합니다…여러분이 필요한 상황을 설정하고 프레임워크를 만들 수는 있지만, 실제로 멘토가 필요로 할 수 있다는 것을 인식하는 것은 멘티의 몫입니다. '이 관계에서 원하는 것이 무엇인지, 내가 당신을 어떻게 도울 수 있다고 느끼는지, 오늘 이곳에 무슨 일로 오시게 됐는지, 무엇을 의논하고 싶은지'(P8) 묻고 싶다.

….you’ve got to put the ball in the mentee’s court…initially we can set things up and create a framework, but it is up to the mentee to actually recognise that they might need you. I would ask “what do you want from this relationship, how do you feel I can help you, what brings you here today and what would you like to discuss” (P8).

글로벌 및 가상 멘토링 - 무엇?

Global and virtual mentoring- What?

지리적으로 국경을 넘나드는 멘토링은 여전히 관계에 관한 것이다.

Mentoring across geographical borders is still about relationships

멘토들은 그들이 다른 지역 출신의 젊은 교육자들을 만나는 것을 어떻게 즐겼는지 설명했고, 관계와 지리적 경계를 넘는 공동체 형성이 멘토와 멘티의 관점을 넓힐 수 있다고 제안했다. 그들은 그들 자신의 지식과 다른 문화에서 온 개인들과의 토론이 그들의 지식에 더해지고, 세계적인 관점을 보여주며 관계를 풍부하게 한다고 지적했다. 몇몇 참가자들은 국가 간 장거리 멘토링 관계를 경험했고, 다른 참가자들은 그렇지 않았다. 그들은 비록 관계가 그들이 어디에서 왔는지 보다는 관련된 사람들에게 달려있다고 느꼈지만, 멘토링 이니셔티브의 향후 반복은 계속해서 국가 전체에 걸쳐 dyads와 일치해야 한다고 제안했다.

The mentors described how they enjoyed meeting young educators from other geographical regions and suggested that relationships and community building across geographical boundaries could broaden perspectives of mentors and mentees. They indicated that discussions with individuals from cultures different than their own other added to their knowledge, showcased global viewpoints and enriched the relationships. Some participants had experience in long-distance mentoring relationships across countries, while others did not. They suggested that future iterations of the mentoring initiative should continue to match dyads across countries although they felt that relationships depended on the people involved rather than where they were from.

"국적에 따른 차이는 보이지 않지만, 어떤 사람들은 더 개방적이거나 쉽거나 다른 사람들은 더 어려울 수 있다는 차이점이 있을 수 있습니다. 어떤 관계들은 다른 관계들보다 쉽습니다. 자기 나라든, 서양 나라든, 아니 어느 나라의 멘토링이든, 기본적이거나 근본적인 차이를 잘 모르겠습니다."

“I don't see international differences, but there could be differences that some people are more open or easy and other people would be more difficult…. Some relationships are easier than others. I don't really see a basic or fundamental difference in mentoring people in your own country or Western countries or any country (P2).”

또한, 많은 참가자들은 높은 평가를 받는 보건 직업 교육자들을 위한 국제 기구를 통해 협력적인 학문뿐만 아니라 교수와 학습에 관한 대화를 풍부하게 하기 위해 교육자들의 국제 커뮤니티를 구축하는 것의 중요성에 대해 이야기했다.

Additionally, many participants talked about the importance of building an international community of educators to enrich conversations about teaching and learning as well as collaborative scholarship through a highly regarded international organisation for health professions educators.

그는 "AMEE 프로그램은 우리를 국제 의료 교육자 단체로, 지역사회로 모이게 했다"고 말했다.“ 공동체적인 것이 정말 중요하다고 생각한다.(P4)

I think the AMEE program has really brought together us as a group of international medical educators, we’ve been brought together as a community. I think that community thing is really important (P4).”

가상 멘토링은 관계 형성에 장벽이 아닙니다.

Virtual mentoring is not a barrier to relationship building

이 계획은 전염병 이전인 2019년에 시행되었지만, 참가자 중 누구도 거리나 온라인 멘토링을 효과적인 멘토링 관계의 장벽으로 인식하지 않았다. "대면이든 원격이든 중요하지 않아요. 모든 것은 관계에 관한 것입니다." 실제로 같은 기관이나 지역에 멘토와 멘티가 있는 사람이라도 전화나 영상통화, 이메일 등으로 소통하는 경우가 많았다. 화상회의에 대한 접근성이 높아지면서 가상 플랫폼이 관계를 맺는 데 장애물이 되지 않는다는 것을 느꼈다. 사실, 그것은 더 효율적이고 전 세계의 멘토들에 대한 접근을 넓힐 수 있다. 그들은 여전히 서로에 대한 기대와 관계 형성에 집중하는 것이 핵심이라고 강조했다.

Though this initiative was implemented in 2019, before the pandemic, none of the participants perceived distance or online mentoring as a barrier to effective mentoring relationships, “it doesn’t matter whether that’s personal face to face, or a distance. It’s about the relationship.” In fact, even those who had mentors and mentees at the same institution or region often communicated via phone or video calls or emails. With increasing access to video conferencing, it was felt that the virtual platform was not a barrier to establishing relationships. In fact, it could be more efficient and widened access to mentors across the world. They emphasised that setting expectations of and for each other and focussing on relationship building were still key.

"멀리서 멘팅을 하는 것은 이메일, 줌 등 우리가 하는 모든 일이 문제가 아닙니다. 직접 대면하든 그렇지 않든 문제는 관계를 구축하지 못할 경우입니다." 근본적인 질문으로 돌아가서 멘토링이 무엇인지, 무엇이 아닌지, 그리고 당신이 올바른 멘토인지에 대한 양측의 기대치에 달려 있습니다.

“I think it’s back to relationship building….mentoring at a distance is not a problem, by e-mail, Zoom, all other things that we do…. a problem that would be face-to-face or not is if the relationship couldn’t be built. It’s down to the expectations of both parties about what mentoring is, what it isn’t and are you the right mentor…back to those fundamental questions (P4).”

논의

Discussion

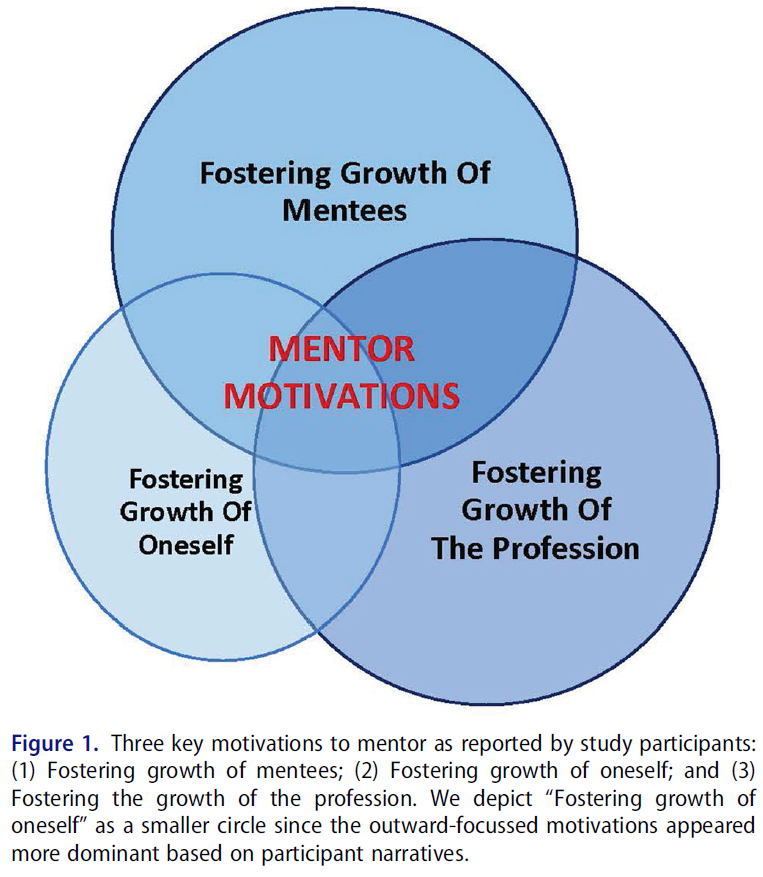

본 연구의 결과는 국제 멘토링 이니셔티브에 자발적으로 참여한 [HPE 리더들의 주요 동기]를 강조한다. 이러한 동기 부여는 그림 1과 같이 세 개의 렌즈를 통해 볼 수 있습니다.

- 먼저 멘티의 성장이다. 멘티가 학문적 과제를 해결하고 전문적으로 성장할 수 있도록 지도하고 싶다는 열망을 강조했는데, 이는 이타적인 동기로 볼 수 있다.

- 다음으로 모두 멘티로부터 얼마나 많은 것을 배웠는지, 멘토링 과정이 어떻게 자신의 성장을 증진시켰는지 집중 조명했다.

- 마지막으로, 전문직에 되갚겠다give back는 약속에 만장일치를 보았고, 멘토링을 이 목표를 달성하기 위한 중요한 수단으로 보았다.

The results of our study highlight key motivations for leaders in HPE, who voluntarily participated in an international mentoring initiative. These motivations can be viewed through three lenses as depicted in Figure 1.

- First, they emphasised a desire to guide mentees in addressing academic challenges and helping them grow professionally, which could be seen as an altruistic motive.

- Next, all of them highlighted how much they learnt from mentees and how the process of mentoring enhanced their own growth.

- Finally, they were unanimous in their commitment to give back to the profession and viewed mentoring as an important vehicle to accomplish this goal.

이러한 모든 발견에 함축적인 것은 멘토가 그러한 의도를 채택하는 것이 실현 가능하고 현실적일 수 있는 그들 자신의 경력에 있을 필요가 있다는 것이다. 아래에서는 참여 멘토(자신에 대한 집중 vs 타인에 대한 집중)의 동기 부여와 함께 멘토 관계의 중심으로서 심리적 안전에 대한 인식을 강조한다.

Implicit in all these findings is that the mentor needs to be at a point in their own careers where adopting such intent was both feasible and realistic. Below, we highlight what motivated participating mentors (a focus on self vs focus on others) as well as their perception of psychological safety as central to mentoring relationships.

이 연구의 참가자는 HPE의 국제적인 리더들로, 그들의 기관과 지리적 지역 밖에서 초보 교육자들을 멘토링하기 위해 자원했다. [그들 자신이 좋은 멘토링을 받았다는 사실]은 젊은 교육자들에게 그들의 경험의 혜택을 전하도록 영감을 주었다(Aryee et al. 1996; Malota 2017). 다른 연구에서는 멘토링을 [자신의 발전을 위한 디딤돌]로 보는 경우가 있다고 보고했지만(Little 1990; Allen 등), 우리의 멘토들은 주요 동기부여요인으로 (자신의) 학문적 발전을 강조하지 않았다. 우리 연구에서 자주 언급되는 동기로는 멘티들의 직업적 발달에 도움을 주고자 하는 [이타주의]가 있었고, 이것이 멘토링 역할을 수용하는 주요 동인이 될 수 있음을 제안한다(배트슨과 파월 2003).

The participants in this study were international leaders in HPE who volunteered to mentor novice educators outside their institutions and geographical region. The fact that they themselves had been recipients of good mentoring inspired them to pass on the benefit of their experience to young educators, similar to reports from the business literature (Aryee et al. 1996; Malota 2017). While other studies have reported that mentors may view mentoring as a stepping stone to their advancement (Little 1990; Allen et al. 1997), our mentors did not emphasise academic advancement as a key motivator. We propose that altruism could be a major driver for acceptance of this international virtual mentoring role based on their frequently stated desire to help mentees in their professional development (Batson and Powell 2003).

[공감-이타주의 가설]은 도움이 필요한 타인을 보며 생기는 감정이입이 이타적 동기를 불러일으킨다는 것이다(배트슨 2019). 비록 이타주의가 더 큰 이기주의 서클 안에 존재하는 것으로 묘사되고, 타인을 돕고자 하는 욕망조차도 종종 자신에게 이익을 주기 위한 동기에 의해 움직인다는 것을 암시하지만, 이타주의의 작지만 유의미한 부분은 분명 이기주의 서클 바깥에 있고, 자기 이익에 대한 욕망에 의해서만 움직이지 않는다(Batson 2019).

The empathy-altruism hypothesis states that empathic emotion, caused by seeing others in need, evokes altruistic motivation (Batson 2019). Although altruism is depicted as existing within a larger egoism circle, suggesting that even the desire to help others is often driven by motives to benefit the self, a small but significant part of altruism is outside the egoism circle and not driven by desire for self-benefit (Batson 2019).

[이타주의-자기중심성 개념]은 타인-초점적이고 자기-초점적인 멘토 동기와도 잘 맞아떨어진다(Beara and Hwangb 2015; Malota 2017). 이러한 국제적 멘토링 맥락에서 멘토링 역할은 전적으로 자발적이었고, 자신에게 직접적인 전문적인 혜택은 없었으며 멘토와 멘티는 사전 관계가 없었으며 상호 작용은 주로 가상적이었다. 따라서, 모든 참여 멘토들이 멘토 관계를 자신의 성장에 기여하는 양방향으로 보고했지만(자기-초점), 그들의 주된 동기는 멘티의 성장을 촉진하고 분야를 발전시키는 것으로 나타났다(타인-초점).

The altruism-egoism concept also aligns well with other-focussed and self-focussed mentor motivations (Beara and Hwangb 2015; Malota 2017). In this international mentoring context, the mentoring role was entirely voluntary, there was no direct professional benefit to themselves, mentors and mentees did not have a prior relationship and the interactions were mainly virtual. Thus, though all participating mentors reported mentoring relationships as bidirectional which contributed to their own growth (self-focus), their primary motivation appeared to be facilitating the growth of mentees and advancing the field (other focus).

멘토링 관계에 대한 접근방법에서는 참가자 전원이 [심리적 안전]이 중요하다고 강조했다. 이를 위해서는 리더가 솔선수범하여 모든 직원과 팀원의 의견을 수렴하고, 모든 수준의 개인이 의견과 우려를 편안하게 표명하며, 다방향 피드백을 장려하는 환경이 필요하다(에드몬슨 2019). 멘토링 관계에서 안전을 확립하기 위한 제안된 전략들은 다음을 포함한다:

- 전문가 뒤에 숨은 '사람'을 알아봄으로써 어색함을 해소한다.

- 멘티가 자신의 안건을 작성하고 계획을 수립하고 그 실행을 전략화하도록 권장한다.

- 멘티가 미래 커뮤니케이션을 계획할 수 있도록 허용한다.

- 비판적 자기성찰을 촉진한다.

- 그들의 열망에 대한 오너십을 갖도록 격려한다.

In terms of approach to mentoring relationships, all participants emphasised that psychological safety is critical. This requires an environment where leaders lead by example and invite input from all staff and team members, individuals at all levels feel comfortable voicing their opinions and concerns, and multidirectional feedback is encouraged (Edmondson 2019). Suggested strategies to establish safety in a mentoring relationship included:

- breaking the ice by getting to know the person behind the professional;

- encouraging mentees to script their own agenda, formulate plans and strategize implementation thereof;

- allowing mentees to plan future communications;

- promoting critical self-reflection; and

- encouraging them to take ownership of their aspirations.

그들 모두는 그들의 관계를 협력적인 것으로 보는 것처럼 보였고, 그것을 'guide on the side'로 접근했다. 따라서 참여 멘토들은 모니터나 모범적인 역할보다는 자발적으로 Losveld 등이 설명한 촉진자 및 코치 역할을 맡는 것으로 나타났다(Loosveld 등 2020). 이러한 접근법은 HPE에서 가끔만 강조되는 [Daloz 멘토링 모델](Daloz 1986)과도 일치한다. 효과적인 멘토 관계는 [지지, 도전, 멘티의 미래 목표에 대한 비전]이라는 세 가지 핵심 요소의 균형을 맞춰야 합니다.

- 너무 많은 지지와 아주 적은 도전은 의미 있는 성장을 촉진할 것 같지 않다;

- 마찬가지로 지원 없이 너무 많은 도전은 개인들을 퇴보하게 할 것이다.

- 효과적인 멘토는 기회를 제공하고 기대치를 설정함으로써 지원과 도전의 균형을 맞춘다(Bower 1998

All of them appeared to view their relationship as collaborative and approached it as a ‘guide on the side.’ Thus, participating mentors spontaneously appeared to take on facilitator and coach roles described by Loosveld et al, rather than the monitor or exemplar roles (Loosveld et al. 2020). These approaches are also consistent with the Daloz model of mentoring (Daloz 1986), the principles of which are infrequently emphasised in HPE. Effective mentoring relationships should balance three key elements – support, challenge and a vision of the mentee’s future goals.

- Too much support and very little challenge are unlikely to foster meaningful growth;

- equally too much challenge without support is likely to cause individuals to regress (Daloz 1986).

- Effective mentors balance support with challenge by providing opportunities and setting expectations (Bower 1998).

멘티와의 관계에 대한 투자가 필수적인 것으로 보고되었지만, 일부 멘토들은 이러한 관계에서 경계를 유지하는 것의 중요성을 강조했다. [경계]는 모든 전문적 관계에서 개인 간의 적절한 행동과 상호작용을 가이드하는 '기초적인 그라운드 룰'으로 설명되었다. 잭슨 등은 이전에 교차 성별 멘토링 관계에서 경계 유지의 중요성을 제기해 왔다(Jackson et al. 우리의 멘토들은 젠더 문제를 우려로 제기하지는 않았지만, 개인의 공간을 침해하지 않고 비밀을 유지하는 등 시간 약속에 대한 명확한 기대감에 대해 구체적으로 논의했다. 균형에 대한 필요성은 그림 2에 설명되어 있습니다.

While investment in relationships with mentees was reported as essential, some mentors emphasised the importance of preserving boundaries in these relationships. Boundaries have been described as ‘basic ground rules’ for any professional relationship, that guide appropriate actions and interactions between individuals (Barnett 2008). Jackson et al. have previously raised the importance of maintaining boundaries in cross-gender mentoring relationships (Jackson et al. 2003). Our mentors did not raise gender issues as a concern, but specifically discussed clear expectations of time commitments, not intruding on one’s personal space and maintaining confidentiality. The need for balance is depicted in Figure 2.

미래 연구는 서로 다른 맥락과 환경 내에서 공통적이고 독특한 촉진제와 장벽을 발견하기 위해 광범위한 지리적 위치의 멘토를 포함해야 한다. 멘토와 멘티의 공유되고 상충되는 인식, 관계의 지속 또는 종말에 영향을 미치는 요소가 무엇인지, 단기 및 장기 관계의 영향을 비교하기 위해, 그리고 마지막으로 멘티, 그리고 마지막으로 멘티, 멘토 및 직업의 성장에 대한 실제 영향을 비교하기 위해서도 필요하다.

Future research should include mentors from a wider range of geographical locations to discover common and unique facilitators and barriers within different contexts and settings. Follow up studies are also needed to examine the shared and conflicting perceptions of mentors and mentees; what factors influence continuation or termination of relationships; compare the impact of short term and long-term relationships; and finally, the actual impact on the growth of the mentee, mentor and the profession.

결론들

Conclusions

우리의 참가자들은 멘토링 이니셔티브에 참여하게 된 세 가지 핵심 요소로 [멘티의 성장, 건강 직업 교육 분야의 성장, 그리고 자신의 성장]을 강조했지만, 처음 두 가지가 이타적이고 더 주된 동기라고 강조했다. 멘토 훈련은 일반적인 'how-to mentor' 기술보다는 육성, 촉진, 코칭 기술에 초점을 맞추고, 심리적 안전 확립에 대한 접근법을 강조하며, 전문직업적 발달에 대한 오너십을 멘티가 갖도록 격려하는 멘토를 양성할 수 있다. 제도적이고 조직적인 멘토링 이니셔티브는 이타적인 동기를 통해, 예를 들어 성찰적인 서술과 비판적인 대화를 통해 분야를 강화하는 데 열정적인 멘토를 식별하는 방법을 찾아냄으로써 더 강력하고 영향력 있는 멘토 관계를 촉진할 수 있다. 기관들은 또한 공감 이타주의 원칙을 만족시키는 안전하고 정의로운 학습과 조직 문화를 보장해야 한다. 예를 들어 상명하달식(top-down)과 타인의 안녕에 대한 진정한 우려와 기쁨을 공개적으로 표현하는 것이 그것이다.

Our participants emphasised three key factors that motivated their participation in mentoring initiatives: growth of the mentee; growth of the field of health professions education, and growth of oneself, but emphasised the first two as altruistic and more dominant motivations. Mentor training could focus on nurturing, facilitating and coaching skills rather than general ‘how-to mentor’ skills, emphasise approaches to establishing psychological safety, and train mentors in encouraging mentees to take ownership of their professional development. Institutional and organisational mentoring initiatives can promote stronger and more impactful mentoring relationships by finding ways in which to identify mentors who are passionate about strengthening the field through altruistic motivations – for example through reflective narratives and critical conversations. Institutions should also ensure a safe and just learning and organisational culture that satisfy empathy altruism principles, such as normalising strengths and weaknesses top-down and overt expression of genuine concern for and joy at the well-being of others.

doi: 10.1080/0142159X.2021.2020739. Online ahead of print.

What sparks a guide on the side? A qualitative study to explore motivations and approaches of mentors in health professions education

PMID: 34985380

Abstract

Introduction: Despite abundant research emphasising the value of mentoring for healthcare professionals, little is known about what motivates mentors. This study aimed to explore what motivated a group of internationally renowned health professions educators to accept informal, international and mostly online mentoring roles, and their approaches to that mentoring.

Methods: Using a qualitative approach, we interviewed ten global educational leaders, who volunteered to serve as mentors in an initiative implemented by the Association for Medical Education in Europe in 2019, via Zoom. The hour-long interviews, conducted between May and October 2019, were audiotaped and transcribed on Zoom. De-identified transcripts were analysed for key themes.

Results: The key themes identified could be mapped to three categories, Motivations - Why; Approaches - How, and Global and virtual mentoring - What. Themes under motivations included: (1) Nurturing relationships focussed on mentees' growth; (2) Pass on the benefit of one's experience; (3) For one's own continued growth. Themes under approaches included: (1) Provide a safe space; (2) Encourage mentees to take ownership of their professional development. Themes under global and virtual mentoring included: (1) Mentoring across geographical borders is still about relationships; (2) Virtual mentoring is not a barrier to relationship building.

Discussion: Though mentors also saw own growth and ongoing professional development as an important benefit of mentoring, altruism or the desire to benefit others, appeared to be a key motivating factor for them. Finding ways in which to identify mentors who are passionate about strengthening the field in this way - for example through reflective narratives and critical conversations - could be key when implementing mentoring initiatives.

Keywords: E-mentoring; Mentoring; mentor motivations; professional development.