의학역량에 대한 질문: COVID-19 사태가 의학교욱의 목표를 바꾸어야 하는가? (Med Tech, 2021)

Questioning medical competence: Should the Covid-19 crisis affect the goals of medical education?

Olle ten Catea , Karen Schultzb , Jason R. Frankc , Marije P. Hennusd , Shelley Rosse , Daniel J. Schumacherf , Linda S. Snellg, Alison J. Whelanh and John Q. Youngi ; on behalf of the ICBME Collaborators

도입 Introduction

2020년 사스-CoV-2 (COVID-19) 대유행은 건강과 교육을 포함한 사회의 많은 부문에 심각한 영향을 끼쳤다. 보건 및 교육에서 학생, 교사, 프로그램 및 기관의 업무 과정과 보건 직업 교육에서의 이들의 교차점에서 일어난 적응은 지속적인 영향을 미칠 수 있고, 우리는 제안할 것이다(루시와 존스턴 2020; 로즈 2020; 하우어 외 2021). 강의실과 임상 교육 모두에서 의학 교육의 많은 적응adaptations이 문서화되었다(Goldhamer 등 2020; Hall 등 2020). 본 논문에서 우리는 이러한 적응에 초점을 맞추지 않고, 전염병이 의료 역량에 대한 우리의 견해에 어떻게 더 근본적으로 영향을 미쳤는지에 초점을 맞추고 있다.

The 2020 SARS-CoV-2 (COVID-19) pandemic has profoundly affected many sectors of society, including health and education. The adaptations that have taken place in the work processes of students, teachers, programs, and institutions in health care and education and their intersection in health professions education could and, we would propose, should have lasting effects (Lucey and Johnston 2020; Rose 2020; Hauer et al. 2021). Many of the adaptations in medical education – in both classroom and clinical education – have been documented (Goldhamer et al. 2020; Hall et al. 2020). In this paper we do not focus on these adaptations, but rather on how the pandemic has more fundamentally affected our views on medical competence.

[역량]에 대한 다양한 정의 중 하나는 '활동을 수행하거나 주어진 과제를 완수하기 위해 개인 또는 사회적 요구에 대응할 수 있는 능력'(IGI Global 2021)이다. 이는 의료 전문가의 경우 [임상 실무에서 직면하는 도전에 대응할 수 있는 능력]이다. 이러한 과제는 환자 안전에 대한 다소간의 위험이 수반될 있으며, 긴급한 대응이 필요할 수도 있고, 준비와 훈련이 필요할 수 있다.

Among the various definitions of competence, one is ‘the capacity to respond to individual or societal demands in order to perform an activity or complete a given task’ (IGI Global 2021), which, for a medical professional, would be the capacity to respond to challenges faced in clinical practice. These challenges may come with more or less risk for patient safety, may need a more or less urgent response, and may require more or less preparedness and training.

- 의료 종사자의 재배치,

- 이러한 근로자가 새로운 업무를 위해 적절히 훈련할 기회,

- 전염병 동안 새로운 업무에 참여할 의사의 의지

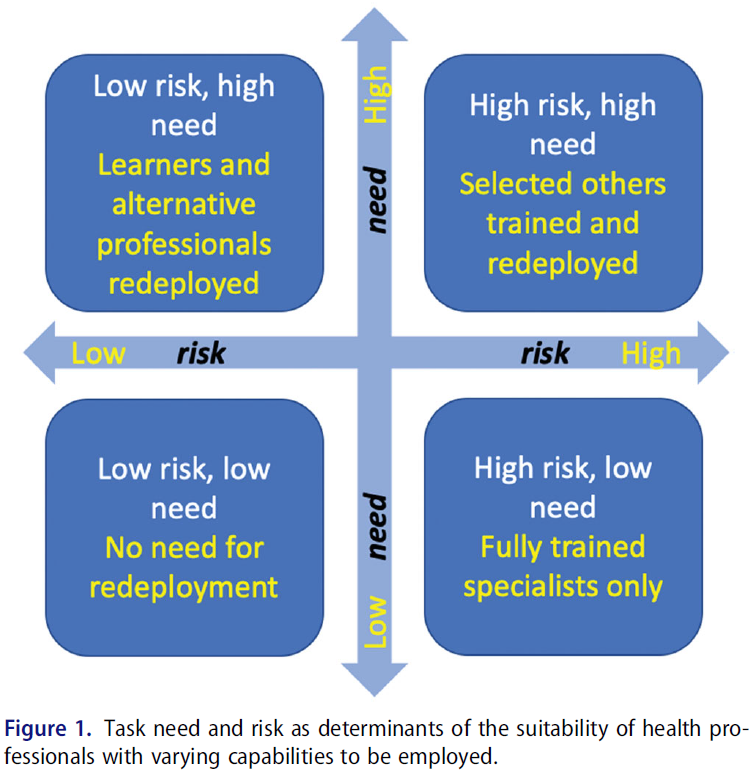

...에 대한 필요성은 이러한 필요성에 대한 [개별 임상의가 이러한 필요, 위험, 개인의 능력을 어떻게 인식하는지]뿐만 아니라, [조치의 필요성] 및 [환자와 의사 모두에 대한 작업의 위험성]에 달려 있었다. 단순화하면 [긴급성]과 [위험 수준]이라는 두 가지 외부 조건이 네 가지 상황을 초래합니다(그림 1).

- The need for redeployment of health care workers,

- the opportunity for these workers to properly train for new tasks, and

- the willingness of physicians to engage in novel tasks during the pandemic

...have depended on the need for action and the risk of the work to both patient and physician, as well as individual clinicians’ perceptions of these needs, the risks, and their personal capabilities. Simplified, the two external conditions – urgency and risk level – lead to four situations (Figure 1).

그림 1 다양한 능력을 갖춘 보건 전문가의 적합성의 결정 요소로서 직무 필요성과 위험.

Figure 1. Task need and risk as determinants of the suitability of health professionals with varying capabilities to be employed.

COVID-19 대유행 기간 동안의 치료는 종종 그림 1의 오른쪽 상단 모서리에 있다. 대유행이 극에 달했을 때 응급 의사, 가족 의사, 전염병 전문의, 집중치료사, 내과 의사 및 호흡기내과 전문의들이 당연히 COVID-19 환자를 돌볼 것을 요청받았다. 하지만, 많은 병원에서는, 이러한 환자들을 돌볼 수 있는 전담 전문가가 너무 적어서, 입원 의학과에 익숙하지 않은 사람들을 포함하여, [다른 전문의들]의 의사들이 자원봉사를 했거나 도움을 요청 받았기 때문에 도움을 주었다. 예를 들어 소아 진료량이 급격히 감소한다는 것은 소아과 의사가 소아 ICU에서 위독한 성인 환자를 돌보도록 요청했다는 것을 의미한다(Kneyber et al. 2020).

Care during the COVID-19 pandemic has often sat in the top right corner of Figure 1. At the peaks of the pandemic, emergency physicians, family physicians, infectious disease specialists, intensivists, internists, and pulmonologists were, not surprisingly, called on to attend to patients with COVID-19. However, in many hospitals, too few dedicated specialists were available to cover the care for these patients, so physicians from other specialties assisted, including ones less familiar with inpatient medicine, either because they volunteered or because they were asked to help. Drastic drops in pediatric care volumes, for instance, meant that pediatricians requested to care for critically ill adult patients in pediatric ICUs (Kneyber et al. 2020).

전문가, 의대, 대학원 프로그램, 면허 기관 및 대중은 모두 [유능한 의사]가 무엇인지에 대한 이미지를 가지고 있지만, 이 용어를 정의하거나 이러한 정의를 조작화하는 것은 항상 어려웠다(Kate 2017). 매우 인용된 정의일지라도, 엡스타인과 헌더트(2002)가 제공한 권위 있는 정의('제공되는 개인과 공동체의 이익을 위해 일상적 실무에서 의사소통, 지식, 기술 기술 기술, 임상적 추론, 감정, 가치 및 성찰의 습관적이고 현명한 사용')는 해석의 여지를 남긴다. 어떤 지식과 기술이 기대될 수 있는지 명시하지 않고, 사람들은 같은 방식으로 표준을 해석하거나 적용할 수 없다. 이는 부분적으로 역량이 상황에 따라 다르다는 사실 때문일 수 있다. (10 케이트 외 2010; 10 케이트 및 빌렛 2014; Teunissen 외 2021).

Professionals, medical schools, postgraduate programs, licensing organizations, and the public all have an image of what a competent physician is, but defining this term, or operationalizing those definitions, has always been difficult (ten Cate 2017). Even highly cited, authoritative definitions, such as the one provided by Epstein and Hundert (2002) (‘the habitual and judicious use of communication, knowledge, technical skills, clinical reasoning, emotions, values, and reflection in daily practice for the benefit of the individual and community being served’), leave room for interpretation to some extent as they do not specify which knowledge and skills may be expected, and people may not interpret or apply the standards in the same way. This may be due to the fact that competence is, in part, context dependent (ten Cate et al. 2010; ten Cate and Billett 2014; Teunissen et al. 2021).

Billett (2017)은 직업 역량의 세 가지 요소 또는 영역을 구분한다:

- 모든 유사한 전문가에 의해 공유되는 표준 도메인,

- 맥락에 의해 결정되는 상황 도메인, 그리고

- 유능한 전문가들 사이에서도 개인의 차이를 설명하는 개인 도메인.

Billett (2017) distinguishes three components or domains of occupational competence:

- a canonical domain, shared by all similar professionals,

- a situational domain determined by the context, and

- a personal domain that explains individual differences, even among competent professionals.

[규칙적인 상황]에서, 대부분의 의사들은 그들의 규범적이고 전문적인 자격과 동료들, 동료들, 그리고 전문 사회의 상황적 지원이 모든 표준과 기대치를 충족하기에 충분한 지침을 제공하는 안정적이고 친숙한 맥락에서 일한다. 그러나 공식적으로 요구되는 능력으로 규정될 수 있는 것에는 한계가 있다. 예를 들어, 어떤 지식은 암묵적이고 성문화하기가 어렵다. COVID-19와 같은 대유행에서 상황 변화는 초기 불확실성과 관련된 능력의 적응을 필요로 한다. 경력 내내 모든 의사는 [불확실한 순간]에 직면한다. 즉, 직업 변화, 새로운 치료와 시술의 치료의 발전, 익숙하지 않은 문제, 희귀 질환 및 표준 임상 지침에 반영되지 않은 비정형 프레젠테이션의 환자(Collianni et al. 2021). 이러한 익숙하지 않은 상황에는 전문가의 판단, 임상적 추론, 행동 및 관리가 새롭게 필요합니다. 프로들은 '미안하지만, 나는 그것을 학교에서 배우지 못했다' 뒤에 숨을 수 없다. 일반적인 사회 및 전문적 기대는 지속적인 자기주도 학습을 통해 의료 질문 및 익숙하지 않은 문제를 가진 환자를 어느 정도까지 보호할 수 있다는 것이다. 다시 말해서 의사는 적응할 수 있을 것이라는 기대를 받는다(10 Kate 등).

In regular circumstances, most physicians work in stable and familiar contexts for which their canonical, professional qualifications, plus contextual support from colleagues, coworkers, and professional societies, provide sufficient guidance to meet all standards and expectations. There is a limit, however, to what can be formally stipulated as required competence. For example, some knowledge is tacit and hard to codify. In a pandemic such as COVID-19, contextual changes require an adaptation of competence, associated with initial uncertainty. Throughout their careers, all physicians face moments of uncertainty: job changes, advances in care with new therapies and procedures, unfamiliar problems, rare diseases, and patients with atypical presentations that are not reflected in canonical clinical guidelines (Colaianni et al. 2021). These unfamiliar situations require renewed professional judgment, clinical reasoning, actions, and care. Professionals cannot hide behind ‘I apologize, but I did not learn that in school’ (Duijn et al. 2020). The general societal and professional expectation is that all physicians can be trusted, to some extent, to care for patients with health care questions and problems with which they are not familiar, through ongoing self-directed learning. Physicians are expected, in other words, to be adaptable (ten Cate et al. 2021).

문제는: 어느 정도의 적응성을 기대하는 것이 합리적인가? COVID-19 대유행은 이 질문을 집중 조명했다. 의사들은 항상 적응할 수 있어야 했지만, 그렇게 빠르고 광범위한 방식으로는 드물었고, 의료 제공자들 스스로가 개인적인 위험에 처하게 된 상황에서, 그렇게 많은 중증 환자들과 함께 있는 경우는 드물었다.

The question is: what adaptability limits define reasonable expectations? The COVID-19 pandemic has spotlighted this question. Physicians have always needed to be adaptable, but rarely in such a rapid and expansive way and rarely with so many profoundly sick patients, in a situation in which the health care providers themselves were put at personal risk.

우리는 마이크로, 메소, 매크로 수준에서 답을 제공하기 보다는 교육적이고 조직적인 질문을 제기한다. 이는 미래 업무의 피할 수 없는 다양성에 대한 건강 전문가의 준비와 적응력에 대한 인식을 높이기 위해서이며, COVID-19 대유행, 다음 대유행 또는 기타 국가 및 글로벌 보건 위기의 세 번째 및 그 이후의 파동을 위한 것이다(그림 2).

We pose educational and organizational questions, rather than providing answers, at the micro, meso, and macro levels, to raise awareness about health professionals’ preparedness and adaptability for the inevitable diversity of future work, be it for third and subsequent waves of the COVID-19 pandemic, the next pandemic, or other national and global health crises (Figure 2).

그림 2 개인, 프로그램 및 제도, 규제 및 사회 시스템의 세 가지 관점에서 의료 위기 동안 의료 역량을 평가합니다.

Figure 2. Valuing medical competence during a health crisis from three perspectives: individual, program and institution, and regulatory and societal systems.

마이크로 레벨: 개별 연수생 및 개업 의사의 관점에서 의료역량 재고

The micro level: Reconsidering medical competence from the perspective of individual trainees and practising physicians

물론 역량은 특정한 일을 수행하는 능력이다. 그렇다면 전문직 역량professional competencce은 전문가에 의해 수행될 것으로 예상되는 직무와 관련이 있는데, 전문가가 권위자로 간주되거나 자문받는 이유는 전문적인 기술, 훈련 또는 지식을 갖추었기 때문이다. 전문가들은 (이미 여러 번 완료했기 때문에) 매우 익숙한 과제뿐만 아니라, (해당 과제가 예상 실무 범위에 포함된다면) 이전에 거의 또는 전혀 수행되지 않은 과제까지도 수행할 것으로 기대된다(Ward et al. 2018). 모든 의학 졸업자는 어느 정도 신뢰받으며, 낯선 업무에 대처할 것으로 예상해야 하지만 문제는 예상되는 실무 범위 내외에서 [어느 정도까지 대처하느냐]이다. 이로 인해 의과대학 선택에서부터 확립된 실무에 이르기까지 의료 경력 주기에 걸쳐 다음과 같은 몇 가지 질문이 제기된다.

Competence, of course, is the ability to perform specific tasks. Professional competence then pertains to professional tasks, those expected to be performed by professionals, often called experts because they are regarded or consulted as an authority on account of special skill, training, or knowledge (Oxford English Dictionary [date unknown]). Experts are expected to perform not only tasks with which they are highly familiar because they have completed them many times, but also tasks they have rarely or never previously performed if those tasks fall within their expected scope of practice (Ward et al. 2018). All medical graduates should be trusted and expected to cope with unfamiliar tasks to a certain extent (ten Cate et al. 2021), but the question is to what extent, both within and outside of an expected scope of practice. This leads to several questions across the medical career cycle, from selection for medical school through established practice:

i. 익숙하지 않은 문제와 불확실성에 대처하기 위해서는 [적응력과 창의적인 문제 해결(능력)]이 필요하며, 이는 다시 에너지와 진취성을 필요로 한다. 불확실한 상황에서 일할 수 있는 적응성 및 의지와 관련된 지원자의 속성을 의대 선택 과정에서 평가해야 하는가? 그리고/또는 학교는 학생들의 이러한 속성을 개발하기 위해 노력해야 하는가? 진취성과 창의성이 (합당한) 기대치expectation가 될 수 있는가? 그리고 그것은 의대를 시작할 때 학생들에게 전달되어야 하는가?

i. Coping with unfamiliar issues and uncertainty requires adaptability and creative problem-solving, which in turn require energy and initiative. Should applicants’ attributes associated with adaptability and willingness to work in uncertain circumstances be assessed in medical school selection processes, and/or should schools work to develop these attributes in their students? Can initiative and creativity become an expectation, and should that be communicated to students when they start medical school?

ii. 이타주의와 용기: [모르는 것은 많지만, 니즈는 높은 환경에서 의료를 제공하는 것]은 기술뿐만 아니라 (도덕적인) 태도도 제공하는 것인가? 그림 1과 같이, 필요량이 가용 리소스를 압도하는 상황에서 재배치에 대한 요구가 발생할 수 있습니다. 필요성이 높고 위험이 낮은 상황(왼쪽 상단 박스 그림 1)은 이타주의를 요구할 수 있다.

- 예: 제공자는 장기간 가족으로부터 떨어져 있어야 할 수 있다.

- 저위험 제공자는 해당 질병을 가지고 있지 않은 환자의 치료를 넘겨받아 고위험 제공자의 시간을 확보할 필요가 있을 수 있다.

- 제공자는 필요 또는 요구를 충족시키기 위해 급여를 받거나 받지 않고 추가 임상 작업을 수행해야 할 수 있습니다.

ii. Altruism and courage: Is providing care in a setting of high need with many unknowns not only a skill set but a (moral) attitude as well? As per Figure 1, calls for redeployment will occur in high-need situations where need overwhelms the available resources. Situations of high need and low risk (top left box Figure 1) may call for altruism (e.g.

- providers may need to be away from family for extended periods of time;

- low-risk providers may need to free up time for high-risk providers by taking over the care of their patients who do not have the disease in question;

- providers may need to do additional clinical work, with or without pay, to meet needs or demands).

환자, 의사 또는 둘 다에게 필요성과 위험이 높은 상황도 용기가 필요할 수 있다. 이는 그림 1의 오른쪽 상단 박스로 나타내며, 여기서는 의료 사업자가 편안한 영역 밖에서, 그러나 스트레스가 많고 불확실한 상황에서 지원 유무에 관계없이 합리적으로 능력 범위 내에서 일하고 있다. 의료 사업자는 [충분한 역량을 가지고 있음에도 참여를 꺼리는 것]에서부터 [환자 안전 또는 팀 또는 자신의 안전 측면에서 상당한 위험을 감수하는 것]까지 그러한 상황에서 다양한 방식으로 대응할 것이다.

Situations of high need and high risk, for patients, physicians, or both, may also require courage. These are represented by the top right box of Figure 1, where health care providers are working outside of their comfort zone, but reasonably within the scope of their abilities, with or without supports, in stressful, uncertain circumstances. Health care providers will respond in a spectrum of ways in such circumstances, from being unwilling to engage even though they have sufficient competence, to taking on substantial risk in terms of either patient safety or the safety of their team or themselves.

스펙트럼의 양쪽 끝은 문제가 있다. 중간 지점은 우리의 질문이 있는 곳이다. 의사로서의 역할에는 환자와 공중 보건에 대한 봉사에 대한 헌신이 수반됩니다. 하지만 이러한 헌신이 어디까지 확장될까요? 의무 요소를 더 직접적으로 설명하려면:

Both ends of the spectrum are problematic.The middle ground is where our questions lie. Being a physician involves a commitment to service – to patients and to public health – but how far does this extend? To state the obligatory element more directly:

- 당신은 의사가 될 수 있지만 익숙하지 않거나 도전적이거나 위험이 높은 환경에서 일하는 것을 거부할 수 있는가?

- 그리고 만약 그렇다면, 가능한 [환자 성과 이득]에 대한 [개인적 위험 수준]이나, 임상적 필요 역량과 비교한 역량 격차와 같이, 그러한 결정에 고려해야 할 윤리적 경계는 무엇인가?

- Can you be a physician but choose to refuse to work in an unfamiliar, challenging, or high-risk setting?

- And if so, what are the ethical boundaries for such decisions, such as level of personal risk compared with possible patient outcome benefit, or the competence gap compared with what is clinically needed.

- 참여하기 전에 지원, 감독, 적절한 보호 및 추가 훈련을 주장할 수 있는가?

- 의무 여부를 결정에 고려할 공공 보건(예: 인구 위협의 정도), 임상의 안전(예: 적절한 보호 장비의 가용성), 임상의사의 역량(예: 사전 경험, 집중 훈련 및 지원의 적절한 조합)의 기본 임계값은 무엇인가?

- Can you, or indeed should you, insist on support, supervision, adequate protection, and further training before engaging?

- What are the basic thresholds of public health (i.e. extent of population threats), clinician safety (e.g. availability of adequate protective equipment), and a clinician’s competence (e.g. adequate combination of prior experience, focused training, and support) that determine whether there is an obligation for any physician to serve?

- 이런 종류의 이타주의나 용기가 기대될 수 있는가? 그리고 의대생들은 훈련을 시작할 때 그들의 경력 동안 그러한 상황에서 행동하도록 요구될 수 있다는 것을 들어야 하는가?

- 그리고 이러한 개인의 용기, 이타주의, 그리고 위험 감수는 [중앙 및 거시적 수준의 지도자들]이 그러한 상황에서 의료 제공자들을 [지원하고 교육하고 보호할 책임을 지는 경우]에만 정당화되어야 하는가?

- Can this type of altruism or courage be expected, and should medical students be told at the start of their training that during their career they may be called on to act in such circumstances?

- And should this individual courage, altruism, and risk-taking be justified only if leaders at the meso and macro levels take responsibility to support, educate, and safeguard health care providers in such circumstances?

iii. 학습자에게 적응력을 교육할 수 있는가(Cutrer et al. 2017). 올바른 호기심, 동기, 사고방식 및 복원력과 같은 마스터 [적응형 학습자]의 특징이 제안되었다(Cutrer et al. 2018). 이러한 개인 속성이 고정되어 있는가, 아니면 교육이 적응형 자기조절기술을 육성할 수 있는가? 학습자를 낯선 사례와 문제에 노출시키고, 이성 내에서 그들에게 도전하고 불확실성에 대처하기 위한 문제 해결 능력을 고의적으로 구축할 수 있도록 신중하게 선택한 것은 적응 능력을 개발하는 데 도움이 될 수 있다. 적응 능력을 포착, 강화 및 평가하기 위한 이러한 접근법은 어느 정도 성공으로 시도되었다(Wijnen-Meijer 외 2013; Kalet 외 2017).

iii. Can learners be trained for adaptability (Cutrer et al. 2017). Master adaptive learner features, such as having the right curiosity, motivation, mindset, and resilience, have been suggested (Cutrer et al. 2018). Are these fixed personal attributes or can education foster skills in adaptive self-regulation? Exposing learners to unfamiliar cases and problems, carefully chosen to challenge them within reason and to enable them to deliberately build problem-solving skills to deal with uncertainty, may serve to develop adaptive skills. Such approaches to capture, reinforce, and assess adaptive skills have been tried with some success (Wijnen-Meijer et al. 2013; Kalet et al. 2017).

iv. 의료 전문가가 현재의 업무 범위 밖에서 일하도록 요청받는다면 어떤 지원이 필요한가? 익숙한 관행에서 익숙하지 않은 관행으로 쉽게 전환하기 위해 '근위 발달 지역ZPD'을 식별할 수 있다. 이 용어를 만든 Vygotsky(1978, 페이지 86)는 이를 '[독립적 문제 해결이 가능한 실제 발달 수준]과 [성인의 지도 또는 능력있는 동료화의 협력을 통한 문제 해결능력으로 결정되는 잠재적 개발 수준] 사이의 거리'로 정의했다. 상급 전문가나 동료에 의한 지도 또는 감독은 격차를 해소하고 안전한 실천뿐만 아니라 개인이 감독 없이 연습하는 법을 배우도록 보장할 수 있다. 이 영역 내에서 학습자나 전문가는 '조건적 역량conditional competence'(즉, 지도와 감독이 사용가능한 경우에만 역량이 있다고 볼 수 있음)을 가지고 있다. 전문가를 지도 및 평가를 받는 학습자의 위치로 되돌리려면 겸손함과 팀 내에서 효과적으로 일할 수 있는 기술이 필요합니다. 이러한 속성은 의과대학 선택 과정에 포함되어야 하며, 훈련과 전문 실무 중에 강화 또는 구축되어야 하는가?

iv. What support is needed if a medical professional is asked to work outside their current scope of practice? To ease a transition from familiar to unfamiliar practice, a ‘zone of proximal development’ may be identified. Vygotsky (1978, p. 86), who coined this term, defined it as ‘the distance between the actual developmental level, as determined by independent problem solving and the level of potential development as determined through problem solving under adult guidance or in collaboration with more capable peers’. Guidance, or supervision, by more advanced experts or peers can bridge the gap and ensure not only safe practice but also that an individual learns to practise without supervision. Within this zone, learners or professionals have ‘conditional competence’, (i.e. competence only if there is guidance and supervision available). Putting professionals back in the position of learners being supervised and assessed will require humility and the skill to work effectively in a team. Should these attributes be included in medical school selection processes and reinforced or built during training and professional practice?

이전에 획득한 기술은 개인이 여러 해 동안 연습한 후 쇠퇴할 수 있다(Choudhry 등 2005; Norcini 등 2017).

- 이전에 훈련했지만 더 이상 진료하지 않는 분야에 대해, 매우 경험이 풍부하지만 전문화된 의료 전문가들에게 기대할 수 있는 것은 무엇인가?

- 전문가들은 한때 보유했지만 더 이상 숙달되지 않은 기술을 필요로 하는 업무에 대해, (기술을 재습득rebuild한 후) 도와달라는 요청을 받았을 때 거절할 수 있는가, 아니면 이러한 활동을 시작하기 전에 적절한 교육과 역량 평가를 받기를 고집할 수 있는가?

의료계와 사회 사이의 사회적 계약은 암묵적으로 이러한 의무를 포함할 수 있지만, 명백하게 원시적인 primum non nocere 원칙(첫째, 해를 끼치지 않음)은 질문될 수 있는 것에 한계를 설정한다.

Previously attained skills may decay after an individual has been in practice for many years (Choudhry et al. 2005; Norcini et al. 2017).

- What can be expected of very experienced, but very specialized medical experts in areas where they previously trained but no longer practise?

- Can these professionals refuse a request that they rebuild these skills and assist with tasks requiring skills they once possessed but no longer have mastery over, or can they insist on receiving proper education and assessment of competence before they take on these activities?

The social contract between the medical profession and society may implicitly include this obligation, but clearly the primum non nocere principle (first, do no harm) sets limits on what can be asked.

다음과 같은 의문이 든다:

- 의료 전문가들에게 짧은 시간 내에 다시 습득할 수 있는, 오랫동안 잊고 있던 기술을 사용하도록 요청할 수 있는가?

- 전문가들에게 [과거에 실행범위에 있었던 적이 없지만], [새로 배운다면 의사나 환자에게 허용되는 수준의 위험 수준에서 적용될 수 있는 기술]을 습득하도록 요청받을 수 있는가?

- 의사로서 [정상적인 진료 범위를 벗어나는 작업이나 훈련을 거부하는 것]이 [허용 가능한 시기]와 [권장되는 시기]는 언제인가?

- Questions that arise include the following: Can medical experts be called on to use long-forgotten skills that can be relearned in a short time?

- Can experts be asked to acquire skills that have never been in their scope of practice but that may be learned and applied with an acceptable level of risk to the practitioner or the patient?

- When is that acceptable and when is it rather advisable for a physician to refuse to work or train outside their normal scope of practice?

메소 레벨: 지역 프로그램 및 기관의 관점에서 의료 역량 재고

The meso level: Reconsidering medical competence from the perspective of local programs and institutions

사실상 전 세계의 모든 의과대학들은 전염병이 시작된 이래로 교육 과정을 적응하도록 강요되어 왔다. 대면 교육은 중단되었고, 교실 교육은 온라인 교육으로 전환되었으며, 임상 로테이션은 일시적으로 연기되거나 대폭 축소되었다(골드해머 외 2020; 루시와 존스턴 2020; 웨인 외 2020). 그러나 동시에 일부 의과대학은 수요가 가장 높은 의료 종사자에 대한 수요를 충족시키기 위해 학생들이 조기 졸업할 수 있도록 했다(바르잔스키와 카타네즈 2020; 콜 2020; 플로트 외 2020). 이러한 제도적 조치는 의료 면허에 필요한 역량을 암시적으로 재정의하거나 역량 평가를 개선하여 이전에 설정한 졸업 시간 전에 훈련 목표를 달성한 학생이 면허를 받을 수 있음을 입증한다. 신중하게 구성된 커리큘럼, 프로그램 평가 프레임워크 요건 및 시험 규칙이 갑자기 유연해졌다. 고정 졸업 기준에 대한 시간의 변동성에 의해 정의될 경우(Frank 등 2010) 역량 기반 의학교육이 학부 교육에서 가능하지 않다는 주장은 반박된 것으로 보인다. COVID-19 사태로 인해 학부 의료 프로그램, 대학원 프로그램 및 기관이 커리큘럼과 평가의 적응을 고려해야 했고, 이로 인해 몇 가지 의문이 제기되었다.

Virtually all medical schools in the world have been forced to adapt their educational processes since the start of the pandemic. Face-to-face education has been suspended, classroom teaching has turned into online education, and clinical rotations have been temporarily postponed or significantly curtailed (Goldhamer et al. 2020; Lucey and Johnston 2020; Wayne et al. 2020). But at the same time, some medical schools enabled students to graduate early (Barzansky and Catanese 2020; Cole 2020; Flotte et al. 2020) to meet the demand for health care workers where the need was highest. These institutional measures implicitly redefined the competence needed for medical licensing or refined the assessment of competence to certify that students who had attained the goals of training before their previously set graduation time could be licensed. Carefully constructed curricula, programmatic assessment framework requirements, and examination rules suddenly became flexible. The argument that competency-based medical education, if defined by more variability in time against fixed graduation standards (Frank et al. 2010), is not possible in undergraduate education, seems to have been refuted. The COVID-19 crisis has required undergraduate medical programs, postgraduate programs, and institutions to think of adapting curricula and assessment, leading to several questions.

v. 미리 설정된 교육 기간의 완료만을 기준으로 하기 보다는, 역량에 따라 학습자의 자격을 더 갖추기 위해, 좀 더 개별화된 커리큘럼이 필요할 것인가? (샌튼 외 2020) 한 가지 접근법은 위탁 가능한 전문 활동(EPA)을 포함할 수 있다. EPA는 학습자가 필요한 역량을 입증하는 즉시 수행할 수 있도록 신뢰할 수 있는 전문 실무 단위이다 (10 Kate 2005, 10 Kate and Taylor 2020). 의사의 진료 범위는 개인화된 EPA 포트폴리오로 생각할 수 있으며, 이는 교육 중에 점진적으로 구축되며, 실무자가 근무 수명 내내 유지 또는 채택한다(10 Kate 및 Carraccio 2019).

v. Will more individualized curricula be needed to qualify learners more on the basis of their competence rather than solely on the basis of their completion of a preset duration of training (Santen et al. 2020)? One approach may include entrustable professional activities (EPAs). EPAs are units of professional practice that learners can be trusted to perform as soon as they have demonstrated the required competence (ten Cate 2005; ten Cate and Taylor 2020). A physician’s scope of practice may be envisioned as an individualized portfolio of credentialed EPAs, which is gradually built during training, and which is maintained or adapted by practitioners throughout their working life (ten Cate and Carraccio 2019).

잠재적으로 졸업 시간을 개별화하는 것에 더하여, 이 접근방식은 COVID-19와 같은 위기 대처에도 유용할 수 있다. 위기 대처에 필요한 작업을 위한 EPA를 명확히 표현할 수 있고, 훈련을 제공할 수 있으며(개인과 기존 기술 세트에 따라 달라질 수 있음), 평가를 구성할 수 있다. 예를 들어 인공호흡기 관리는 EPA(Hester et al. 2020)로 형성될shaped 수 있다. 특정 영역의 역량을 공식적으로 외부적으로 회수할 수 있는 인식인 디지털 배징은 EPA(Mehta et al. 2013)의 사용에 완벽하게 적합한 개발인 보다 개별화된 역량 프로파일(Norcini 2020; Noyes et al. 2020)을 만들도록 최근 권고되었다.

In addition to potentially individualizing times of graduation, this approach may also prove useful in addressing crises such as COVID-19. EPAs for the work needed to deal with the crisis can be articulated, training can be provided (the nature and extent of which would vary depending on the individual and their existing skill sets), and assessment can be organized. Ventilator management, for example, could well be shaped as an EPA (Hester et al. 2020). Digital badging, a formalized and externally retrievable recognition of competence in an area, has recently been recommended to create a more individualized profile of competence (Norcini 2020; Noyes et al. 2020), a development that would perfectly fit with the use of EPAs (Mehta et al. 2013).

vi. 학교, 기관, 전문 기관 및 작업 그룹은 '급속 배치rapid deployment' 모듈 또는 부트캠프 활동을 만들고 필요할 때 제공해야 하는가(헤스터 외 2020)? 새로운 주제를 중심으로 국내 또는 국제적으로 이러한 커리큘럼을 공유할 수 있는 저장소가 있어야 하는가? 병원은 의과대학과 협력하여 신속한 배치 팀을 구성하여, 군 예비군과 유사한 비상 기술을 정기적으로 업데이트하여 위기에 직접 대응하고 더 많은 인력을 재배치 및/또는 훈련시켜야 한다. [위기 대비]와 [일상적인 치료를 위한 자원 요구] 사이에 최적의 지점은 어디인가?

vi. Should schools, institutions, professional organizations, and working groups create ‘rapid deployment’ modules or bootcamp activities and offer them when needed (Hester et al. 2020)? Should there be a repository where such curricula can be shared nationally or internationally around emerging topics? Should hospitals in collaboration with medical schools create rapid-deployment teams, regularly updating their emergency skills, in analogy with the military reserves, to respond to crises directly, while simultaneously redirecting and/or training a larger workforce? Where is the sweet spot between crisis preparedness and resource needs for routine care?

vii. 기관들은 위기 상황에서, 위기의 니즈와 전체적으로 일치하는 전담 맞춤형 팀들이 신속하게 조립될 수 있도록, 의료인력의 [기술 세트skill sets의 목록inventory]을 가지고 있어야 하는가? 위기의 시기에 모든 팀이 필요로 하는 간헐적으로 강화되어야 하는 기초적인 기술이 있는가?

vii. Should institutions maintain an inventory of the skill sets of their workforce such that in times of crisis, dedicated bespoke teams whose skill sets collectively match the needs of the crisis can be quickly assembled? Are there foundational skills that all teams would need during times of crisis that should be intermittently reinforced?

매크로 수준: 광범위한 규제, 시스템 및 사회적 관점에서 의료 역량 재고

The macro level: Reconsidering medical competence from a broader regulatory, systems, and societal perspective

많은 사회와 그 정부는 인구의 건강을 보호하고 육성할 의무를 가지고 있다. 이는 대개 환자의 치료를 허가하는 행위이며 환자의 역량을 인정하는 것을 반영하는 것으로 관할 지역의 의료 사업자의 면허를 책임지는 규제 기관을 통해 이루어진다. 또한 헌법이나 후속 개정 또는 법률을 통해 유능한 인력을 확보하고 시민을 위한 접근 권한을 제공하는 것을 포함한다. 전염병이 강조했듯이, 위험 완화를 위해 유능한 인력을 보호하고 지원하는 것도 조직의 책임이다. COVID-19 위기는 의료 및 과학 전문가와의 대화에서 전염병과 싸우고 치료를 확보하고 지원해야 할 정부의 책임을 다시 한번 전면에 부각시켰다. 그들의 결정은 인구 질병률과 사망률에 지대한 영향을 미친다.

Many societies and their governments hold obligations to protect and foster their population’s health. This is usually done through regulatory bodies responsible for the licensing of health care providers in their jurisdiction, which is an act of permission to treat patients and reflects a recognition of their competence. It also involves securing a competent workforce and providing access to care for citizens, either through a constitution or in subsequent amendments or laws. As the pandemic has highlighted, it is also the responsibility of organizations to protect and support that competent workforce to mitigate risk to a tenable level. The COVID-19 crisis has once again brought to the forefront the responsibility of governments to fight pandemics and to secure and support care, in a dialogue with medical and scientific experts. Their decisions have a profound impact on population morbidity and mortality.

급성 치료가 필요한 환자 급증과 같이 필요성이 높은 경우 의료 참여에 대한 조직 차원의 허가 자격은 필요에 따라 유연해질 수 있다. 면허 요건은 때때로 장애물이 될 수 있다.

- 외국 출신 의료 전문가의 경우, 대부분의 경우 의료 면허를 위한 국가시험이 있는데, 이것은 수십 년 전에 다른 나라에서 그들 자신의 면허 요건을 완료한 하위 전문가들에게는 충족되기 어려울 수도 있다.

- 동시에 그러한 하위 전문가들은 위기 관리에 도움이 될 관심 하위 영역(예: 집중 치료)에 대한 최근 경험을 가지고 있을 수 있다.

When the need is high, such as in situations in which a surge of patients require acute care, qualifications for organizational-level permission to participate in health care may become flexible out of necessity. Licensing requirements may sometimes be an obstacle.

- Foreign medical specialists coming to most countries face the requirement of national examinations at the level of medical licensure, which may be difficult to meet for subspecialists who completed their own licensing requirements decades ago in another country.

- At the same time, those same subspecialists may have recent experience in the subdomain of interest (e.g. intensive care) that would be helpful in the management of the crisis.

vii. 규제당국과 국회의원은 예를 들어 필요한 경우 더 작은 범위의 독립적 실무에 대해 제한된 면허를 가진 의사를 허가하기 위한 조건을 재고해야 하는가? 고급advanced 의학 학습자에게도 이런 일이 일어날 수 있을까요? COVID-19 대유행에서 볼 수 있듯이, 갑작스런 건강 재해로 인해 병원은 통상적인 훈련 없이 보건 전문가를 모집해야 할 수 있다. 이러한 필요를 충족시키기 위해 그림 1의 차원들을 고려해야 한다.

- (a) (양적 및 질적으로) 추가 인력의 긴급 요구

- (b) 작업의 위험(즉, 환자와 의료 종사자 모두의 치료 중 부작용의 위험) 및

- (c) 재배치에 이용 가능한 자들의 경험 수준.

viii. Should regulators and lawmakers rethink the conditions for licensing physicians, for example, with restricted licences for a smaller scope of independent practice if needed? Could this happen with advanced medical learners? As seen in the COVID-19 pandemic, sudden health disasters can result in hospitals needing to recruit health professionals without the usual training. In meeting this need, the dimensions included in Figure 1 must be considered:

- (a) the urgent need for extra hands (in quality and quantity),

- (b) the danger of the work (i.e. the risks of adverse events during care for both patients and health care workers) and

- (c) the level of experience of those available for redeployment.

세 가지 차원 모두 스케일 값을 가지며, 낮음 또는 높음일 수 있으며, 신중한 조합이 배포의 허용 가능성(또는 라이센스 정식 위탁)을 결정할 수 있습니다.

All three dimensions have scale values and may be low or high, and a thoughtful combination may determine the acceptability of deployment (or, if you will, formal entrustment with a license).

ix. 적절한 감염 관리 정책, 충분한 개인 보호 장비, 훈련 기회 및 보상 구조와 같은 의료 종사자의 재배치를 요청할 때 [지역, 주 및 연방 당국의 상호적인 의무]는 무엇인가? 이러한 부족한 인력을 법적 영향으로부터 보호하기 위해 재해가 의사들에게 현재 실무 범위를 초과하여 일할 것을 요구하는 경우(또는 규제자가 요구할 경우) 책임 규칙을 채택해야 하는가?

ix. What are the reciprocal obligations of local, state, and federal authorities when requesting redeployment of health care workers, such as adequate infection control policies, sufficient personal protective equipment, training opportunities, and reward structures (Antommaria 2020)? Should liability rules be adapted if a disaster demands (or a regulator requires) physicians to work beyond their current scope of practice, to protect these scarce workforces from legal repercussions?

x. 보건 위기가 지나가서, 의료 전문가의 필요성이 평상시 수준으로 돌아간 다음에는 어떻게 되어야 하는가? 위기의 대응으로 긴급 면허가 유지되어야 하는가? 아니면 유효기간이 있어야 할까? 위기 경험은 어떤 식으로든 믿을 수 있는가? 그리고 우리는 다음 위기에 더 잘 대비하기 위해 배운 교훈을 어떻게 이용할까?

x. What happens after the health crisis has passed, and the need for health care professionals returns to normal requirements? Does the emergency licensing done in response to the crisis persist? Or does it have an expiry date? Can crisis experiences be credentialed in any way? And how do we use the lessons learned to better prepare for the next crisis?

고찰 Discussion

산업화된 세계의 의사들과 교육자들은 예측 가능한 방향으로 의료 역량을 생각하기 위해 움직였을지도 모른다. COVID-19 위기는 새로운 질병이 어떻게 많은 문제를 야기하는지, 그리고 관리 권고안이 어떻게 수개월에 걸쳐 바뀔 수 있는지를 일반 대중에게 보여주었다. 이는 '유능한 의사'조차도 항상 무엇이 최선인지 알지 못하고 불확실성으로 압도될 수 있는 방법을 강조한다. 현재와 같은 위기상황에서, 어떻게 우리가 대응하도록 인력을 최적화할 수 있을까요?

Physicians and educators in the industrialized world may have moved to think of medical competence in a predictable direction. The COVID-19 crisis has revealed to the general public how a new disease creates many challenges and how recommendations for management can change over a period of months. This highlights how even ‘competent physicians’ do not always know what is best and can be overwhelmed with uncertainty. In a crisis like the current one, the question comes up: How can we optimize the workforce to respond?

우리의 관찰과 질문의 일반적인 결론은 [의료 기관]과 [규제 기관]뿐만 아니라 [의사]들도 사회의 건강 요구가 적응을 요구할 때 [개별적으로 그리고 집단적으로] 적응할 준비를 해야 한다는 것이다. 이것은 의료 능력 표준의 개념화에 영향을 미친다. COVID-19 위기는 이러한 표준이 이전에 생각했던 것보다 덜 정적인 것일 수 있다는 것을 알게 했다.

The general conclusion of our observations and questions is that physicians, as well as health institutions and regulatory bodies, should be prepared, individually and collectively, to adapt when the health needs of society call for adaptation. This has implications for the conceptualization of standards of medical competence. The COVID-19 crisis has made us aware that these standards may be less static than we previously believed.

Med Teach. 2021 Jul;43(7):817-823.

doi: 10.1080/0142159X.2021.1928619. Epub 2021 May 27.

Questioning medical competence: Should the Covid-19 crisis affect the goals of medical education?

Olle Ten Cate 1, Karen Schultz 2, Jason R Frank 3, Marije P Hennus 4, Shelley Ross 5, Daniel J Schumacher 6, Linda S Snell 7, Alison J Whelan 8, John Q Young 9

Affiliations collapse

Affiliations

- 1Center for Research Development of Education, University Medical Center Utrecht, Utrecht, The Netherlands.

- 2Department of Family Medicine, Queen's University, Queen's University, Kingston, Canada.

- 3Royal College of Physicians and Surgeons of Canada and Department of Emergency Medicine, University of Ottawa, Ottawa, Canada.

- 4University Medical Center Utrecht, Utrecht, The Netherlands.

- 5CBAS Program in the Department of Family Medicine, University of Alberta, Edmonton, Canada.

- 6Division of Emergency Medicine, Cincinnati Children's Hospital Medical Center and the University of Cincinnati College of Medicine, Cincinnati, Ohio, USA.

- 7Royal College of Physicians and Surgeons of Canada, McGill University, Montreal, Canada.

- 8Association of American Medical Colleges, Washington DC, USA.

- 9Department of Psychiatry, Donald and Barbara Zucker School of Medicine at Hofstra/Northwell and the Zucker Hillside Hospital at Northwell Health, Glen Oaks, NY, USA.

- PMID: 34043931

- DOI: 10.1080/0142159X.2021.1928619AbstractKeywords: Learning outcomes; curriculum; outcome-based.

- The COVID-19 pandemic has disrupted many societal institutions, including health care and education. Although the pandemic's impact was initially assumed to be temporary, there is growing conviction that medical education might change more permanently. The International Competency-based Medical Education (ICBME) collaborators, scholars devoted to improving physician training, deliberated how the pandemic raises questions about medical competence. We formulated 12 broad-reaching issues for discussion, grouped into micro-, meso-, and macro-level questions. At the individual micro level, we ask questions about adaptability, coping with uncertainty, and the value and limitations of clinical courage. At the institutional meso level, we question whether curricula could include more than core entrustable professional activities (EPAs) and focus on individualized, dynamic, and adaptable portfolios of EPAs that, at any moment, reflect current competence and preparedness for disasters. At the regulatory and societal macro level, should conditions for licensing be reconsidered? Should rules of liability be adapted to match the need for rapid redeployment? We do not propose a blueprint for the future of medical training but rather aim to provoke discussions needed to build a workforce that is competent to cope with future health care crises.

'Articles (Medical Education) > 대학의학, 조직, 리더십' 카테고리의 다른 글

| 역량바탕평가가 지속적인 개혁이 되기 위해 고려할 점(Adv in Health Sci Educ, 2019) (0) | 2021.11.12 |

|---|---|

| 의학교육에서 디자인 씽킹의 힘 (Acad Radiol, 2019) (0) | 2021.11.08 |

| 신화와 사회적 구조: 참을 수 없는 집합적 신화의 필요성 (Med Educ, 2020) (0) | 2021.08.29 |

| 역량바탕의학교육의 도입: 평가의 문화를 변화시키고 있는가? (Med Teach, 2019) (0) | 2021.07.24 |

| 대학의학에서 주임교수들의 요구 이해(Acad Med, 2013) (0) | 2021.07.22 |