의사의 정체성 이행: '이도저도 아닌' 상태에 있기로 선택하다 (Med Educ, 2019)

Doctors’ identity transitions: Choosing to occupy a state of ‘betwixt and between’

Lisi Gordon1,2 | Charlotte E. Rees2,3 | Divya Jindal-Snape4

1 | 소개

1 | INTRODUCTION

의료 전문가는 자신의 경력 동안 수많은 이행transition을 경험한다.1-3 [사회 구성주의 관점]에서 이행은 [맥락, 대인 관계 및 정체성의 변화로 인해 시간이 지남에 따라 발생하는 심리, 사회 및 교육적 적응의 지속적인 과정]으로 정의할 수 있다.4 의사들의 전이 경험을 다중적이고 복잡하고 지속적인 것으로 개념화함으로써, 우리는 이러한 경험을 집중적인 학습을 위한 시기로 간주할 수 있다.4-10

Health care professionals experience numerous transitions during his or her career.1-3 From a social constructionist viewpoint, transitions can be defined as ongoing processes of psychological, social and educational adaptations over time necessitated by changes in context, interpersonal relationships and identities.4 By conceptualising doctors’ experiences of transitions as multiple, complex and ongoing, we can regard these experiences as times for intensive learning, but also as periods of increased stress and burnout.4-10

이전의 이행 연구는 [새로운 역할에 대한 공식 및 비공식 학습 기회의 증가]를 중심으로, [의사의 이행에 대한 개인화된 접근 방식]을 우선시하는 것으로 나타났습니다. 이는 의사 입장에서 [이행 경험을 탐색하는 과정]으로써, 의사의 안녕과 조직, 그리고 궁극적으로 환자에게 필수적인 것으로 여겨집니다. 이전의 연구는 [의사들의 과도기 경험]에 대한 지원과 도전들에 초점을 맞추었다면, 본 연구는 상위 단계 수련생의 [전문직업적 정체성 전환]과, 이 수련생들이 [이행 중의 의사]에 대한 이해를 높이고, 이에 대비하기 위해 [어떻게 한계성liminality을 경험하는지]에 초점을 맞추어 연구를 확대한다.

Previous transitions research suggests that priority be given to personalised approaches to doctors’ transitions, with increased opportunities for formal and informal learning about new roles.8 This is seen as fundamental to doctors’ well-being, to his or her organisation and ultimately to patients as doctors navigate transition experiences.8 Whereas previous research has centred on the support for, and challenges of, doctors’ transition experiences,5-10 this study extends this research by focusing on higher-stage trainees’ professional identity transitions and how such trainees experience liminality in order to better enhance understandings of, and provisions for, doctors in transition.

즉각적인 명확화를 위해, [사회 구성주의 관점]에서, 우리는 [전문직업적 정체성]을 [역동적으로, 대화와 상호작용을 통해 형성되고 재형성formed and reformed되는 것]으로 개념화합니다(정체성 작업identity work이라고도 함, 아래 참조).11 전통적 인류학적 의미에서 [한계성liminality]은 (여성 사춘기 통과의례와 같이) [의식화된 사건이 기존의 지위에서 새로운 지위로의 전환을 용이하게 하는 맥락에서 두 지위(예: 소녀도 아니지만, 아직 여성이 아닌) 사이에 존재하는 상태]를 설명하는 것으로 정의된다.12,13 따라서 상급 단계 수련생의 이행과정이라는 맥락에서, 리미널리티는 [수련생에서 훈련받은 의사로 이행하는 동안(예: 의사가 컨설턴트가 되는 경우)] 경험하게 되며, 이 때 의사에 대한 기대치의 변화가 수반된다. 그러나 우리는 한계성을 이 인류학적 정의보다 더 복잡한 방식으로 개념화하며, 이것을 아래에 상세히 기술한다.

To offer immediate clarification, from a social constructionist perspective, we conceptualise professional identities as dynamic, and as formed and reformed through dialogue and interaction (also known as identity work; see below).11 Liminality, in the traditional anthropological sense, is defined as describing the condition of being betwixt and between two positions (eg, as not a girl but not yet a woman) in a context in which a ritualised occurrence facilitates the shift from an old to a new status, such as in female puberty rites of passage.12,13 Thus, within the context of higher-stage trainees’ transitions, liminality may be experienced during the transition from trainee to trained doctor (such as when a doctor becomes a consultant), alongside changing expectations of doctors that support these liminal experiences. We conceptualise liminality in a more complex manner than this anthropological definition, however, and we articulate this in detail below.

1.1 | 신원 확인 작업

1.1 | Identity work

첫째, 우리는 '정체성 작업identity work'이 의미하는 바를 명확히 표현합니다. 정체성 작업은 [전문직과 같은 특정 사회 집단의 구성원이 되는 사람들이 경험하는 지향적 과정orienting process]이라고 볼 수 있다.14 직업적 전환기 동안에 정체성 작업은 전면에 드러납니다.

- 개인적, 가족 구성원과 같은 중요한 타인으로써(개인적),

- 옛 동료와 새 동료로서(전문직업적),

- 여러 영역에서 복잡하고 역동적인 변화의 씨름으로써(사회적, 문화적, 심리적, 물리적).

First, we articulate what we mean by ‘identity work.' Identity work can be considered an orienting process experienced by people through which people become members of particular social groups such as professional ones.14 During times of workplace transition, identity work comes to the fore as

- individuals and his or her significant others such as family members (personal), and

- old and new colleagues (professional),

- grapple with complex and dynamic changes in multiple domains (eg, social, cultural, psychological and physical).4,8

사회 구성주의 관점에서, [정체성]은 [언어, 상징, 의미와 가치의 집합을 포함한 다양한 방법으로 개인적 경험, 타인 및 조직을 통해 함께 그려진다].15 [정체성 작업]은 '...사람들이 그들의 정체성을 형성, 수리, 유지, 강화 및 수정하는 데 관여하는 것'을 말한다.16

From a social constructionist perspective, identities are drawn together through personal experiences, others and organisations in numerous ways, including through language, symbols, sets of meanings and values.15 Identity work refers to ‘… people being engaged in forming, repairing, maintaining, strengthening and revising their identities.'16

따라서, [정체성 작업]은 새로운 정체성을 개발하고, 묘사하고, 지원하기 위한 노력이다. 또한 정체성 작업은 [경합적인 대화]와 [다양한 경험] 사이의 상호작용에서 의미가 도출되는 성찰적 서술로 개념화할 수 있다. 개인은 특정 정체성 투사project할 수 있으며(즉, 정체성 주장claim identities), 다른 사람들은 이렇게 '투사된 정체성projected identities'를 진실authentic하다고(또는 진실되지 않다고) 지지하거나(예: 허용grant), 혹은 주장되거나 거절될claimed or rejected 특정한 정체성을 개개인에게 부여bestow on할 수도 있다.

Thus, identity work endeavours to develop, portray and support new identities, and can be conceptualised as a reflexive narrative in which meaning is derived from interaction between contending dialogues and a range of experiences.17 Individuals will project certain identities (ie, claim identities), as others simultaneously support (ie, grant) those projected identities as authentic (or not) and may also bestow on individuals certain identities that may be either claimed or rejected.17-20

정체성 구성 과정에서 필수적인 요소로서, 이러한 [정체성 주장과 허용claims and grants]은 자아로부터 비롯되거나, 다른 사람의 말에서부터 비롯되거나, 그리고 비언어적 커뮤니케이션에서 비롯될 수 있다.21,22 그러한 정체성 구성은 그것이 [공동 구성]이든 [다른 사람과 경쟁을 벌이는 것]이든 간에 개인의 [자기 서술]의 일부가 된다.20,23 따라서 정체성 작업의 성과는 '맥락적 담론의 강점과 유연성pliability'에 의해 협상되고, 부여된 정체성에 대한 개개인의 해석을 통해 협상된다. 더욱이, 정체성 작업을 [개개인이 안전한secure 자아 의식sense of self을 위해 노력하는 일시적인, 선형적 과정]으로 개념화하는 것은 옳지 않다. 실제로, [직업적 불안]이나 [경력 전환]과 같은 상황은 사람들이 '자기 의식을 만들고, 확인하고, 분쇄하기 위해' 노력을 기울이는 정체성 작업를 촉진할 수 있다.

As vital elements in identity construction processes, these identity claims and grants can stem from self and other talk, plus non-verbal communication.21,22 Such identity construction, whether it is co-constructed or contested by others, becomes part of an individual’s self-narrative.20,23 The outcomes of identity work are, therefore, negotiated by the ‘strength and pliability of contextual discourses’ and through individual interpretations of identities granted.20 Furthermore, conceptualisations of identity work as a transient, linear process in which individuals strive towards a secure sense of self can be challenged.24 Indeed, situations such as job insecurity or career transitions may actually catalyse identity work, whereby people expend efforts to ‘create, confirm and disrupt a sense of self.'24

1.2 | 정체성과 경계성

1.2 | Identities and liminality

더 넓은 문헌을 탐구하면서 우리는 [커리어 전환]은 종종 ['내가 누구인가']에 대한 감각이 ['내가 누가 되고 있는가']라는 감각에 자리를 내주는 [역동적인 경계 단계dynamic liminal phase]에 의해 정의될 수 있음을 발견한다.25 경계성liminality에 대한 기존의 선형적 개념에서 벗어나, 현재는 [정체성 전환]이 덜 의식화되며, 새로운 정체성으로의 집합은 종종 불완전하게be partial 이뤄진다고 본다.

- 예를 들어, 경영학 문헌의 한 연구는 [낙하산 대원 지망생]에서 [낙하산 대원]으로의 전환을 묘사하고 있는데, 새로운 정체성에 대한 인식은 [대중 앞에서의 임관식]을 거치며 만들어지는 것이 아니라, [조용한 심사숙고 중]에 일어난다.

- 마찬가지로 영국(영국)에서도 의사들의 transitions out of traning은 교육 수료증(CCT)을 발급받고 전문의 등록부에 포함되는 [의례적인 절차]를 수반한다. 그러나, 의사들은 이러한 전환을 [지속적이고 복잡한 것]으로 경험하며, 단순히 CCT를 받는 것을 넘어서, [자기자신의 전문의로서의 새로운 의사 정체성을 인지]하는 데 어느정도의 시간이 걸린다는 것을 암시합니다.

Exploring the wider literature, we find that career transitions can often be delineated by a dynamic liminal phase, in which the sense of ‘who I am’ gives way to a sense of ‘who I’m becoming.'25 Moving away from traditional, linear notions of liminality, current conceptualisations suggest that identity shifts are less ritualised and aggregation to new identities can often be partial.26

- For example, a study from the management literature articulates the shift from aspiring paratrooper to paratrooper, in which recognition of the new identity happens during quiet contemplation rather than through a public passing out ceremony.27

- Similarly, in the United Kingdom (UK) doctors’ transitions out of training involve the ceremonial process of receiving a certificate of completion of training (CCT) and inclusion on the specialist register.

- However, our research suggests that doctors experience this transition as ongoing and complex such that his or her personal recognition of his or her new specialist doctor identity takes time beyond the simple receiving of a CCT.8

이러한 [중간상태in-betweenness]는 시공간적으로 한정되어 불확실성과 연계되어 있는 듯 하다.26-30 따라서, [리미널리티]는 종종 '사회 제도에서 자신의 내면적 자아와 위치에 대한 현저한 교란'으로 묘사된다. 26-30 연구자들은 그러한 교란이 개인들로 하여금 [강렬한 정체성 작업]을 통해 [리미널(경계적) 지위를 해결할 필요]가 있게 할 수 있다고 주장한다.30 실제로, 개인은 이러한 [경계 공간을 가로질러 이동]하기 위해 자신과 다른 사람들에게 중요한 방식으로 정체성을 개발합니다. Beech는 상당한 경계 기간을 경험하는 사람들은 과거, 현재, 미래를 언급함으로써 [시간순적으로 위치를 잡기도position themselve 한다]고 주장한다. [(과거에 대한) 자기 성찰]과 [미래 자아 투사]를 통해 리미너liminar는 리미너 공간liminal space을 벗어나기 위해 [앞뒤를 동시에 바라보는 것]으로 볼 수 있다. 이러한 방식으로 개념화된 리미널리티는 ['일시적'인 것]으로 생각된다.

This state of in-betweenness is seen as bounded in space and time and linked to uncertainty.26-30 Thus, liminality is often portrayed as something that ‘significantly disrupts one’s internal sense of self and place in a social system.'26-30 Researchers argue that such disruptions can bring individuals to need to resolve his or her liminal status through intense identity work.30 Indeed, individuals develop identities in ways that are important to themselves and others in order to move across these liminal spaces.23,26 Beech argues that people experiencing significant periods of liminality also position themselves chronologically by referring to the past, present and future.26 Through engagement in self-reflection and projecting a future-self, these liminars can be seen as simultaneously looking forwards and backwards in order to move out of the liminal space. Liminality, conceptualised in this way, is thought to be 'temporary.'26,31,32

그러나 Ybema 등은 [영구적 리미널리티perpetual liminality]의 개념을 도입함으로써 리미널리티에 대한 보다 복잡하고 사회적인 이해를 설명하였다. [영구적 경계성]은 개인이 [상황적, 사회적, 시간적 관련성relevant을 갖기 위해 정체성 확인 작업을 수행하는 상태]를 말한다.23 영구적 경계성은 [비정규직 근로자(예: 대리 의사)]와 [이중 역할 전문가(예: 의사-관리자)]와 같이 지속적인 중간 상태를 경험하는 근로자에게 가장 뚜렷하게 나타난다.32-34 일시적 경계성은 '더 이상 X-가 아니지만 아직 Y도 아니다'라는 느낌을 만드는 반면, 영구 한계성은 'X-도 아니고 Y도 아닌 존재' 또는 'X-와 Y가 모두 되는 것'이라는 [지속적인 느낌]을 만들어낸다.23 일시적 경계성과 마찬가지로, 영구적 경계성은 흔히 다른 사람들에 의해 부과되며, 소위 경계의 브리콜루어(브리콜라지를 하는 사람)라고 불리는 사람이 되는 것이다. 브리콜루어는 [정체성 작업]을 사용하여 '시시각각 시간에 서로 다른 관객들에 따라 자신에게 다른 역할을 주기cast and recast'를 한다.

Ybema et al,23 however, have described more complex and social understandings of liminality by introducing the notion of perpetual liminality. Perpetual liminality is a state in which individuals undertake identity work to make themselves contextually, socially and temporally relevant.23 This perpetual liminality is most evident in workers experiencing enduring in-betweenness, such as impermanent workers (eg, locum doctors) and dual-role professionals (eg, clinician-managers).32-34 Whereas temporary liminality creates a feeling of ‘not-X-anymore-butnot-yet-Y,' perpetual liminality creates an ongoing sense of ‘being neither-X-nor-Y’ or ‘being both-X-and-Y.'23 As with temporary liminality, perpetual liminality is often imposed by others, with individuals becoming so-called boundary bricoleurs, who use identity work to ‘cast and re-cast themselves to different audiences at different times.'23,35

[일시적 경계성]에 대한 이해가 선형적이라면, [영구적 경계인]은 [이전과 새로운 자아에 대한 시간적 성찰에 덜 의존]한다.23 대신, 그들은 [지속적으로 정체성을 전환]함으로써 즉각적인 경쟁적 요구와 충성도에 대응하고, 따라서 [지속적인 예측 불가능을 경험]하고 사회적인 '노맨스 랜드'에 거주하는 것에 익숙해진다. 그들은 '노맨스 랜드'를 '충성을 쌓는 운영 기반'으로 활용한다. 문헌에 따르면, 이러한 장기간 지속되는 경계감은 [불확실성과 중간성의 지속적인 감정]을 통해서 [부정적인 정서적 결과]를 초래할 수 있다.

In a manner that differs from more linear understandings of temporary liminality, perpetual liminars rely less on temporal reflections of their old and new selves.23 Instead, they respond to immediate competing demands and loyalties by continuously switching identities, thus experiencing lasting unpredictability and growing accustomed to inhabiting a social ‘no-man’s land,' which they employ as an ‘operating base to build allegiances.'23 The literature suggests that this long-lasting sense of liminality can lead to negative emotional consequences as a result of ongoing feelings of uncertainty and in-betweenness.'29, 35

1.3 | 리미날리티 및 의료 교육

1.3 | Liminality and health care education

상위 의학 교육 저널의 키워드 검색('리미날*' 용어를 사용)에서는 학습자가 전문적 정체성을 개발하는 데 어려움을 겪는 어려운 지식troublesome knowledge에 어떻게 직면하는지에 대해 [학부 학습의 임계값 개념]에 대해 상당한 연구가 존재한다는 것을 보여줍니다.36,37 [지식의 임계값 개념]은 학습자가 (종종 적절하다고 여겨지는 행동을 모방하는 것처럼) 진실성 부족을 경험할 때 [반드시 거쳐야 하는 포털]에 비유되며, [경계성 시기liminal phase]로 묘사될 수 있다.38 학습자의 초점은 이러한 [문턱을 넘어서 학습자가 개념과 세계를 인식하는 방식을 바꾸는 [변혁적 학습]]에 있습니다. .37 이러한 의료 교육 연구 영역은 종종 정확한 임계 개념의 목록(예: 돌봄 또는 책임)을 얻는 데 초점을 맞춘다.39-42

A keyword search (using the term ‘liminal*’) of top medical education journals reveals that considerable research exists around threshold concepts in undergraduate learning with reference to how learners are confronted with troublesome knowledge that challenges his or her developing professional identities.36,37 The notion of knowledge as threshold is likened to a portal through which learners must travel when experiencing a lack of authenticity, often imitating behaviours considered appropriate, and described as a liminal phase.38 The focus for learners is on moving through these thresholds and on to transformational learning, which changes the ways learners perceive concepts and the world around them.37 This sphere of health care education research often centres on obtaining a definitive list of threshold concepts (eg, caring or responsibility).39-42

그러나 여기에는 확인되지 않은 질문이 있다. 바로 학습자가 [문제 지식]에서부터 [경계 단계]를 거쳐 [혁신적 학습]에 다다를 것이라는 생각(즉, 일시적 경계성)이다. 예를 들어, 브라운 외 연구진은 두 정체성 사이의 일시적 경계성 단계를 stressful하다고 표현하기 위해 [의료 전문가에서 교육자로의 전환]에 대한 선형적 개념화를 사용했다.43 다른 이들은 논의 물리적 공간을 [경계적liminal]이라고 초점을 두었다. 예를 들어서, 병원 복도와 같은 곳을 토론과 지식 교환과 비공식 학습을 위한 [경계성 공간]으로 본다거나, 어떻게 새로운 의과대학 건물이 [전문직]과 [대학] 사이의 경계 공간이 되는가를 연구했다.44,45

Relevant here, however, is the unquestioned notion in this literature that learners will progress from troublesome knowledge through a liminal phase to transformational learning (so, temporary liminality).36 For example, Browne et al used a linear conceptualisation of the transition from medical professional to educator to describe the temporary liminal phase between the two identities as stressful.43 Others have focused on physical spaces as liminal, such as the hospital corridor as a liminal space for discussion, knowledge exchange and informal learning, or how a new medical school building becomes a liminal space between the profession and the university.44,45

1.4 | 연구 목적 및 연구 질문

1.4 | Study aims and research questions

우리의 연구 질문은 다음과 같습니다.

Our research questions are:

1. 수련생이 훈련한 전환 과정을 거치면서 의사가 설명하는 경계적 경험(및 이와 관련된 정체성 작업)은 무엇입니까?

1. What liminal experiences (and associated identity work) do doctors narrate as he or she moves through trainee-trained transitions?

2. 훈련생으로 전환되는 동안 경계적 경험(및 이와 관련된 정체성 작업)은 시간이 지남에 따라 어떻게 변화합니까?2. How do liminal experiences (and associated identity work) change over time during trainee-trained transitions?

2 | 방법

2 | METHODS

2.1 | 연구 설계

2.1 | Study design

본 논문은 수련생으로 양성된 의사들의 전환을 탐구하는 보다 폭넓은 종단적 서술연구에서 나온 것이다.8 종단적 서술 탐구를 통해 시간이 지남에 따라 각 참가자들의 독특한 경험을 탐구할 수 있었다.46 종방향 오디오 다이어리(LAD)는 스토리텔링을 전경화하고 출입구 인터뷰와 함께 참가자가 세로 방향으로 깊이 있는 경험을 탐색할 수 있도록 지원하기 때문에 변경 시 감지 도구로 특히 적합합니다.46,47

This paper comes from a wider longitudinal narrative study exploring trainee-trained doctors’ transitions.8 Longitudinal narrative inquiry allowed us to explore the unique experiences of each participant over time.46 Longitudinal audio-diaries (LADs) are particularly applicable as sense-making tools during times of change because they foreground storytelling and, used alongside entrance and exit interviews, help participants to explore his or her experiences in depth longitudinally.46,47

2.2 | 샘플링 및 모집

2.2 | Sampling and recruitment

영국 의사들은 대학 졸업 후 일반적으로 2년간의 Foundation 교육을 받은 후 [전공과목specialty 교육]으로 옮기기 시작하는데, 전문 분야에 따라 3년에서 8년 사이의 기간이 소요될 수 있습니다. 전문대학 평가의 성공적인 완료에 따라, 수습생은 [CCT를 취득]하고 [전문의 등록부specialty register]에 등록됩니다. 우리는 의도적으로 향후 6개월 이내에 CCT를 확보할 것으로 예상되는 영국의 수련의들을 표본 추출하여 수련의들이 수련을 받은 경험을 종적으로 탐구할 수 있도록 했습니다. 본 논문의 목적상, 우리는 이러한 의사들을 전체적으로 '훈련된 의사들trained doctor'이라고 설명한다. 훈련 완료 후 여러 가능한 목적지를 설명하는 일반 용어이기 때문이다(예: 컨설턴트, 일반의사 [GP], 임상 펠로우).

Following university graduation, UK doctors typically begin postgraduate training with 2 years of Foundation training before moving to specialty training, which can take anything between 3 and 8 years (depending on the specialty). Following the successful completion of specialty college assessments, the trainee achieves a CCT and is placed on the specialty register. We purposely sampled UK trainee doctors expected to secure CCTs within the following 6 months to allow us to longitudinally explore doctors trainee-trained experiences. For the purposes of this paper, we describe these doctors throughout as ‘trained doctors’ as this is a generic term accounting for multiple possible destinations following completion of training (eg, consultant, general practitioner [GP], clinical fellow).

2.3 | 데이터 수집

2.3 | Data collection

초기 면접에서 참가자들은 전환에 대한 이해도와 다가오는 전환에서 기대하는 바를 질문 받았다. 참가자들은 또한 지금까지의 훈련 경험을 되새기고, 훈련된 전환 준비에 어떤 영향을 미쳤는지에 대해 토론했습니다. 그런 다음 참가자들은 LAD 단계에 참여하도록 초대되었습니다. 이 단계에서 참가자들은 6~9개월에 걸쳐 훈련받은 전환 경험과 관련된 이야기, 생각, 성찰 등을 기록하도록 요청받았다.

At entrance interview, participants were asked about his or her understanding of transitions and what he or she expected from his or her upcoming transitions. Participants also reflected on his or her training experiences to date and discussed what influenced his or her readiness for trainee-trained transitions. Participants were then invited to participate in the LAD phase. During this phase, participants were asked to record stories, thoughts and reflections pertaining to trainee-trained transition experiences over 6-9 months.

표 1은 세 단계에 걸쳐 수집된 데이터와 각 참가자에 대한 인구통계 정보를 보여줍니다.

Table 1 depicts the data collected across the three phases, as well as demographic information for each participant.

2.4 | 데이터 분석

2.4 | Data analysis

우리는 먼저 프레임워크 분석을 사용하여 데이터 집합의 광범위한 테마를 유도적으로 식별했다.51 이 테마 분석에는 여러 단계가 포함되었다.

- (a) 광범위한 연구팀(승인서 참조)의 구성원은 반복적인 기록 탐사와 오디오 녹음을 통해 데이터에 익숙해졌다.

- (b) 주제 프레임워크는 각 연구팀이 데이터의 하위 집합을 별도로 분석하고 주요 테마를 제안하도록 한 다음, 팀이 코딩 프레임워크에 대한 고차 주제를 함께 협상할 수 있도록 함으로써 개발되었다.

- (c) 이러한 고차 테마는 atlas.ti 버전 7.0(ATLAS.ti, 과학 소프트웨어 개발 GmbH, 독일 베를린)을 사용하여 모든 데이터를 코드화하기 위해 사용되었다. 가장 중요한 주제는 의사 수련생이 훈련한 전환의 다양한 경험에 보다 광범위하게 초점을 맞추고 전환에 대한 촉진자 및 억제자를 식별했다.8

We first used framework analysis to inductively identify broad themes in our dataset.51 This thematic analysis involved several stages:

- (a) members of the wider research team (see Acknowledgements) familiarised themselves with the data through repeated explorations of transcripts and audiorecordings;

- (b) a thematic framework was developed by having each research team member separately analyse a subset of data and propose key themes and then allowing the team to negotiate higher-order themes for the coding framework together, and

- (c) these higher-order themes were utilised to code all data using atlas.ti Version 7.0 (ATLAS.ti, Scientific Software Development GmbH, Berlin, Germany). The overarching themes focused more broadly on the multiple experiences of doctors’ trainee-trained transitions, identifying facilitators and inhibitors to transitions.8

3 | 결과

3 | RESULTS

세 가지 학습 단계를 모두 마친 참가자들은 [전공의trainee]에서 [전문의trained doctor]로의 이행과정에서 자신의 정체성과 관련된 경계성을 경험했다. 이전 문헌과 일관되게 데이터 분석을 통해 참가자의 경험에서 일시적이고 영구적인 경계성을 파악할 수 있었습니다. 그러나 참가자의 정체성 대화에 대한 세분화된 분석을 통해 우리는 새로운 한계 경험, 즉 훈련된 의사 지위와 관련된 [다른 사람들로부터의 정체성 부여를 적극적으로 거부]하는 일부 참가자의 여정에서 포인트를 식별할 수 있었습니다. 대신, 참가자들은 (수련생도 훈련된 의사도 아닌) 자신의 [경계적 지위를 유지]하거나 [적극적으로 수련생 신분을 유지]하는 정체성 작업에 착수했다. 우리는 이러한 새로운 유형의 리미날리티를 [점유적 리미날리티occupying liminality]로 설명한다.

All participants completing the three study stages experienced liminality related to his or her identity as he or she moved from trainee to trained doctor. Consistent with previous literature, our data analysis enabled us to identify temporary and perpetual liminality in participants’ experiences. However, fine-grained analysis of participants’ identity talk also enabled us to identify novel liminal experiences: points in some participants’ journeys at which he or she actively rejected identity grants from others associated with his or her trained doctor status. Instead, participants undertook identity work that either maintained his or her liminal positions (as neither trainee nor trained doctor) or that actively maintained a trainee identity; we describe this novel type of liminality as occupying liminality.

3.1 | 일시적인 한계성을 설명하는 의사들

3.1 | Doctors narrating temporary liminality

대부분의 의사들은 자신의 이행단계에 걸쳐 [일시적 경계성 정체성]을 서술했다; 이것은 이미 자리trained post를 확보했지만, 아직 시작을 기다리고 있는 의사들에게 특히 관련이 있었다. 이 시점에서 이들 참가자들은 CCT에 대한 서류 작업을 완료하고 새로운 역할에 대한 기대를 가지고 있었지만, 또한 경험에 대한 반성을 하고 있었다. 예를 들어, Andrew는 [정체성 작업]을 통해 컨설턴트로서 첫 당직 근무를 할 수 있다는 자신감을 나타냈습니다(표 2, 견적 1). 돌이켜보면, 그는 (다른 사람들이 그에게 컨설턴트 신분을 부여하는 것과 함께) 컨설턴트 역할을 했던 이전의 경험이 자신을 잘 준비시켜주었다는 것을 깨달았다.

Most doctors narrated temporary liminal identities at some point across his or her transitions; this was particularly pertinent for doctors who had already secured trained posts but were waiting to start them. At this point, these participants had completed the paperwork for the CCT and were looking forward to the new roles but were also reflecting backward on the experiences. For example, Andrew used identity work to project his confidence in doing his first on-call shift as a consultant (Table 2, Quote 1). Looking backwards, he recognised that his previous experiences of acti ng up as a consul tant (wi th others granti ng hi m a consul tant identity) had prepared him well.

[일시적 경계성 단계]에서, 일부 의사들은 [공식적인 CCT 서류 작업]이 어떻게 완료되었는지 설명했지만, 아직 공식적인 역할을 시작하지는 못했다고 말했습니다([서류 작업 완료]와 [실질적인 '훈련된trained' 직책을 맡는 것] 사이의 이 시차time lag는 영국에서 일반적이다). Steven's와 Arun의 경험에서 확인된다 (표 2, 인용문 2, 3). 임상진료clinical practice에 초점을 맞춘 이러한 각각의 경험에서, 두 의사는 자신의 [훈련된 의사]의 신분을 주장하면서도, 여전히 다른 사람의 신분을 허락받기를 기다리고 있었다.

Some doctors in this temporary liminal phase described how his or her formal CCT paperwork was complete, but that he or she were yet to start his or her formal roles (this time lag between the completion of paperwork and the taking up of a substantive ‘trained’ post is common in the UK), as illustrated by Steven’s and Arun’s experiences (Table 2, Quotes 2 and 3). In each of these experiences, focused on clinical practice, both doctors claimed his or her trained doctor identities but were still waiting for others’ grants of these identities.

다른 의사들은 이 경계성 기간liminal period 동안 그들이 새로운 [컨설턴트 신분]을 주장할 수 있도록 돕는 [의식ritual의 중요성]을 설명했습니다. 이는 특히 George가 논의한 바와 같이, 아직 수련 현장에 남아 있는 상황에서 [시니어 역할]로 이동하는 것을 보여준다signify는 점에서 중요했습니다(표 2, 인용 4).

Other doctors described the importance of rituals (eg, celebrations with colleagues) in helping them claim his or her new consultant identities through this liminal period. This was especially important to signify doctors moving into senior roles in contexts in which he or she remained at the site of his or her training, as discussed by George ( Table 2, Quote 4).

어떤 이들은 일시적인 경계성의 경험을 [긍정적으로 묘사]한 반면(예: Andrew, Steven, Arun 및 George[표 2, 인용문 1-4]), 다른 이들은 [trained doctor 신분의 부여가 다른 사람들에 의해 억제된다]고 인식하면서 좌절감을 경험했다. 예를 들어, 헤더는 자신이 컨설턴트로서 기능하고 있다고 설명함으로써 컨설턴트 신분을 스스로 주장했지만, 그녀는 또한 자신이 여전히 훈련생이라고 설명했으며, 다른 사람들이 [중요한 의사결정 회의에서 자신을 배제함]으로써 컨설턴트 정체성 인정identity grants를 보류했다고 보고했다(표 2, 인용 5).

Whereas some described the experiences of temporary liminality positively (eg, Andrew, Steven, Arun and George[Table 2, Quotes 1-4]), others experienced frustration as he or she perceived that grants of trained doctor identities were withheld by others. For example, although Heather claimed a consultant identity for herself by explaining that she was functioning as a consultant, she also described that she was still a trainee and reported that others withheld consultant identity grants to her by excluding her from important decision-making meetings (Table 2, Quote 5).

3.2 |영구적 한계성을 설명하는 의사들

3.2 | Doctors narrating perpetual liminality

어떤 의사들은 종종 [이중 역할의 소유]를 통해 [영속적 경계성]을 이야기했다. 예를 들어, 임상 관리자 역할을 맡았던 Petra는 다른 사람들이 다양한 환경에서 자신을 어떻게 보는지에 대해 논의했습니다(표 3, 인용문 1). 영국에서 새로 교육을 받은 의사에게 이러한 역할은 드문 일이지만, 국유화되지 않은 의료 시스템에서 의사가 교육 후 즉시 관리 책임을 지는 것은 드문 일이 아닙니다. 먼저, 페트라는 managerial role을 수행함에 있어서, 자신이 그 팀이나 직장의 [확고한fixed 구성원이 아니라는 점]을 감안하여 임상의로서의 [집중적인 정체성 작업]을 사용하여 [다른 임상의와 관계를 구축]하는 방법에 대해 이야기했습니다.

Some doctors narrated perpetual liminality, often through the possession of dual roles. For example, Petra, who had a clinical manager role, discussed how others saw her in the different environments (Table 3, Quote 1). Note that although this role is unusual in the UK for a newly trained doctor, it is not unusual in non-nationalised systems of health care for doctors to have management responsibilities immediately post-training. First, Petra talked about how, in her managerial role, she used intensive identity work as a clinician to build relationships with other clinicians given that she was not a fixed member of that team or workplace.

둘째, 패트라는 자신이 운영회의management meeting에 참석했을 때 다른 사람들이 자신을 매니저로만 생각해서, 그녀도 임상의라는 사실을 잊은 채 어떻게 다른 임상의들에 대해서 불만을 늘어놓았는지를 이야기했다. 그러나 페트라는 자신을 임상의이자 관리자로 보았고, 이러한 두 세계의 경험을 통해 [서로 다른 집단의 관점을 중개하려고 노력]했습니다. 또 다른 참가자인 [GP 임상 학자clinical academic]인 프레디는 Petra와는 다른 방식으로 영구적 경계성을 경험했습니다. 가정의학 개업의 자격을 갖춘 GP로 매주 하루씩 소속된 Freddie는 근무 시간 이외의 회의에 참석하는 등 임상 팀의 일원으로 자리매김하기 위해 정체성 작업에 착수했습니다(표 3의 인용문 2). 이와 함께 그는 임상학자의 역할 8개월 만에 연구 기간이 끝날 때까지 임상학자clinical academic로서 자신의 정체성에 의문을 품었다. 실제로, 그의 정체성 투쟁은 [임상 실무의 정규직]도 아니고, [학계의 정회원도 아닌] 그의 감정을 반영했다(표 3, 인용 3).

Second, she described how, when sitting in management meetings, others saw her as a manager, forgetting that she was also a clinician as the others complained about clinicians. Petra, however, saw herself as someone who was both a clinician and a manager and used this experience of both worlds to try and broker the different group views. Another participant, Freddie, a GP clinical academic, experienced perpetual liminality in a different way to Petra. Affiliated for 1 day per week as a qualified GP to a family medicine practice, Freddie undertook identity work to try to establish himself as part of the clinical team, such as by going to meetings outside his working hours (Table 3, Quote 2). Alongside this, he questioned his identity as a clinical academic until the very end of his time in the study, 8 months into his clinical academic role. Indeed, his identity struggles mirrored his feelings of being neither a full-time member of the clinical practice nor a full member of the academic community (Table 3, Quote 3).

3.3 | 점유적 경계성을 설명하는 의사들

3.3 | Doctors narrating occupying liminality

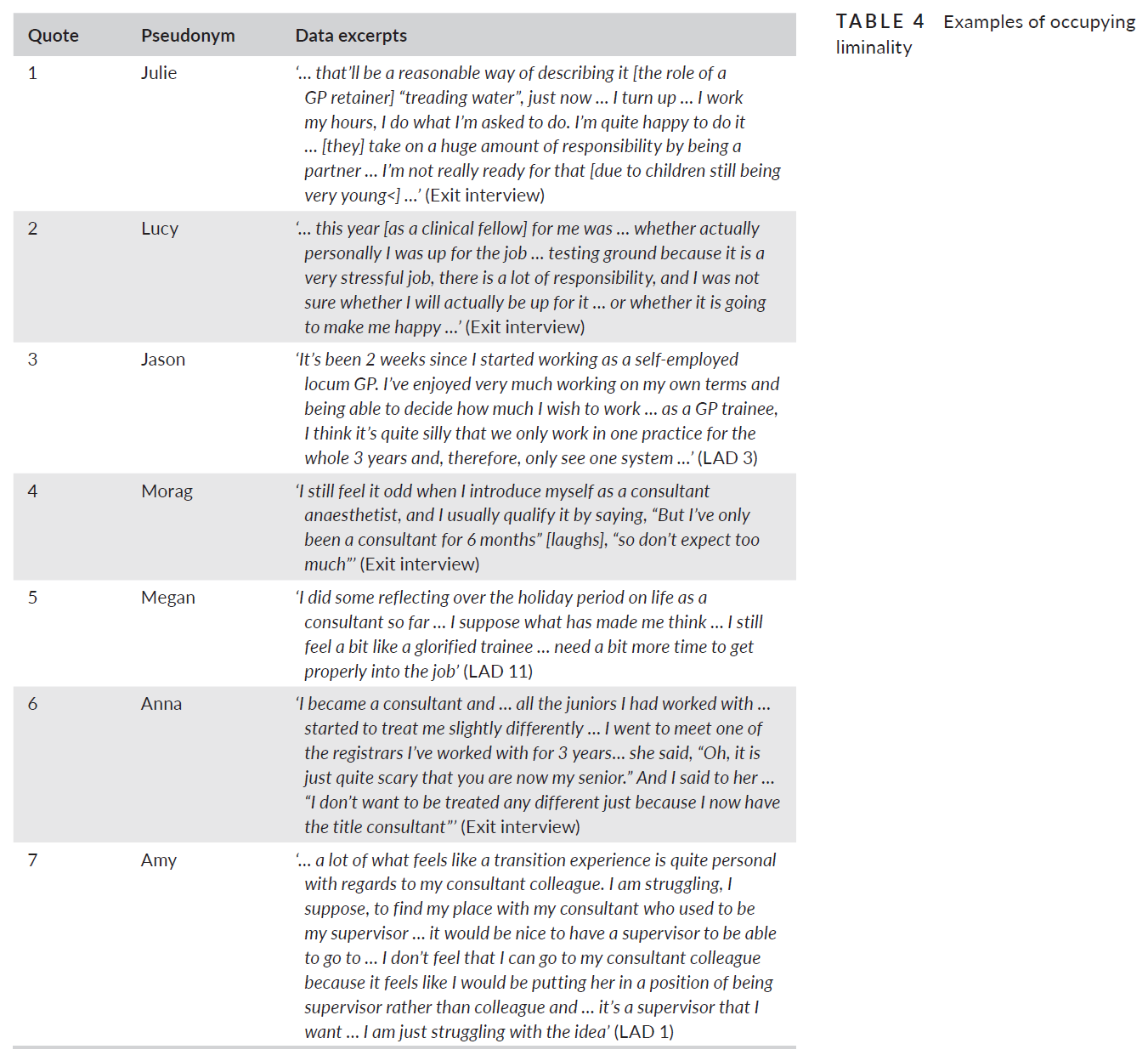

일부 참가자가 [점유적 경계성]을 서술하는 것으로 판명된 한 가지 방법은, [영구적 경계인]으로 능동적으로 포지셔닝하는 커리어 선택을 통해서였다. 이러한 선택의 이유에는 [훈련된 의사 책임]에 대해 더 준비가 되어 있다고 느낄 때까지 기다리려는 욕구와 유연하게 일하고 싶은 욕구가 있었다. 예를 들어, Julie는 자신을 '물 건너가기treading water'라고 표현했습니다(더 영구적인 자리를 원할 때까지 지역 훈련 기관에서 시간제로 일하도록 지원하는 GP). 그녀는 아직 자녀가 매우 어리고, 파트타임으로 일했기 때문에, GP 파트너가 됨으로써 따르는 책임을 원치 않았고, 그래서 그녀는 경계적인 역할을 선택했습니다(표 4). 인용문 1).

One way by which we identified some participants as narrating occupying liminality was through his or her career choices as participants actively positioned themselves as perpetual liminars. The reasons for these choices included a desire to wait until he or she felt more ready for trained doctor responsibilities and a wish to work flexibly. For example, Julie described herself as ‘treading water’ as a retained GP (a GP funded by the local training body to work part-time until he or she wants a more permanent position), and as choosing to be in a liminal role as she did not want the responsibility of being a GP partner as her children were very young and she worked part-time (Table 4, Quote 1).

마찬가지로, 외과의사인 루시는 자신의 전공분야specialty에 머물고 싶은지 결정하기 위해 1년 동안 임상연구원을 선택했다(표 4, 인용문 2). 또 다른 GP인 Jason은 업무 유연성을 유지하고 다양한 직업 환경을 경험하기 위해 대리의사locum으로 일하기로 결정했습니다(표 4, 견적 3). 흥미롭게도, 모든 종단적 데이터 집합에서, 우리는 연구참여자들이 [훈련된 의사로서의 정체성에 대한 주장 또는 인정을 거부rejected]한 무수한 사례를 확인할 수 있었다. 예를 들어, Morag와 Megan은 [전문의 정체성의 수여grants를 거부하기 위해] 정체성 작업을 사용했다.

Similarly, Lucy, a surgeon, chose to be a clinical fellow for a year in order to decide whether she wanted to stay in her specialty (Table 4, Quote 2). Another GP, Jason, chose to work as a locum to maintain work flexibility and to experience different occupational environments (Table 4, Quote 3). Interestingly, across our longitudinal dataset, we were able to identify numerous occurrences within and across participants in which he or she rejected claims and/or grants of his or her trained identities. For example, both Morag and Megan used identity work to reject grants of the consultant identities;

더욱이, 일부 참여자들은 [과거에 동료]였지만 [지금은 후배]가 된 동료들과의 관계 변화에 대응하기 위해 정체성 작업을 수행했음을 이야기했다. 예를 들어, Anna는 동료들 중 한 명이 이제 Anna가 컨설턴트가 된 것을 '무서워했음'을 알게 되었다고 설명했으며, Anna는 이러한 동료 관계를 유지하기 위해 정체성 작업을 사용했다고 한다(표 4, 인용 6). 에이미의 일기장에서, 그녀는 이전에 그녀의 [교육 감독관]이었던 컨설턴트 동료와의 관계가 변한 것에 대해 논의했다. 이 일기들을 통해 에이미는 이런 상황에서, 자신의 [컨설턴트 정체성을 거부하는 것을 선택]했다고 밝히면서, 이전 교육 감독관과의 관계에서는 연습생trainee 정체성을 차지occupy하는 것을 선호했다. 에이미는 자신의 다이어리에 정체성 작업을 통해 이를 통해 컨설턴트 동료의 지원을 여전히 원하지만, [더 이상 감독받고자 해서는 안 된다는 생각]에 대해서 어려움을 겪고 있다고 주장했다(표 4, 인용문 7).

Moreover, some participants discussed undertaking identity work in order to respond to changing relationships with colleagues who had previously been peers but were now more junior. For example, Anna explained that one of her peers found it ‘scary’ that Anna was now a consultant, and Anna employed identity work to try and maintain this peer relationship (Table 4, Quote 6). In Amy’s diaries, she discussed the changed relationship she had with a consultant colleague who had previously been her educational supervisor. Through these diaries, Amy revealed that she was choosing to reject her consultant identity in this circumstance, preferring to occupy a trainee identity in her relationship with her previous educational supervisor. Amy employed identity work in her diaries to talk through this, positioning herself as a trainee by claiming that she still wanted support from her consultant colleague and was struggling with the (self-imposed) notion that she should not be seeking supervision anymore (Table 4, Quote 7).

3.4 | 카렌의 종단적 이야기

3.4 | Karen’s longitudinal story

3.4.1 | 카렌의 일시적 한계: 더 이상 연습생도 아니고 컨설턴트도 아닙니다.

3.4.1 | Karen’s temporary liminality: No longer a trainee but not a consultant either

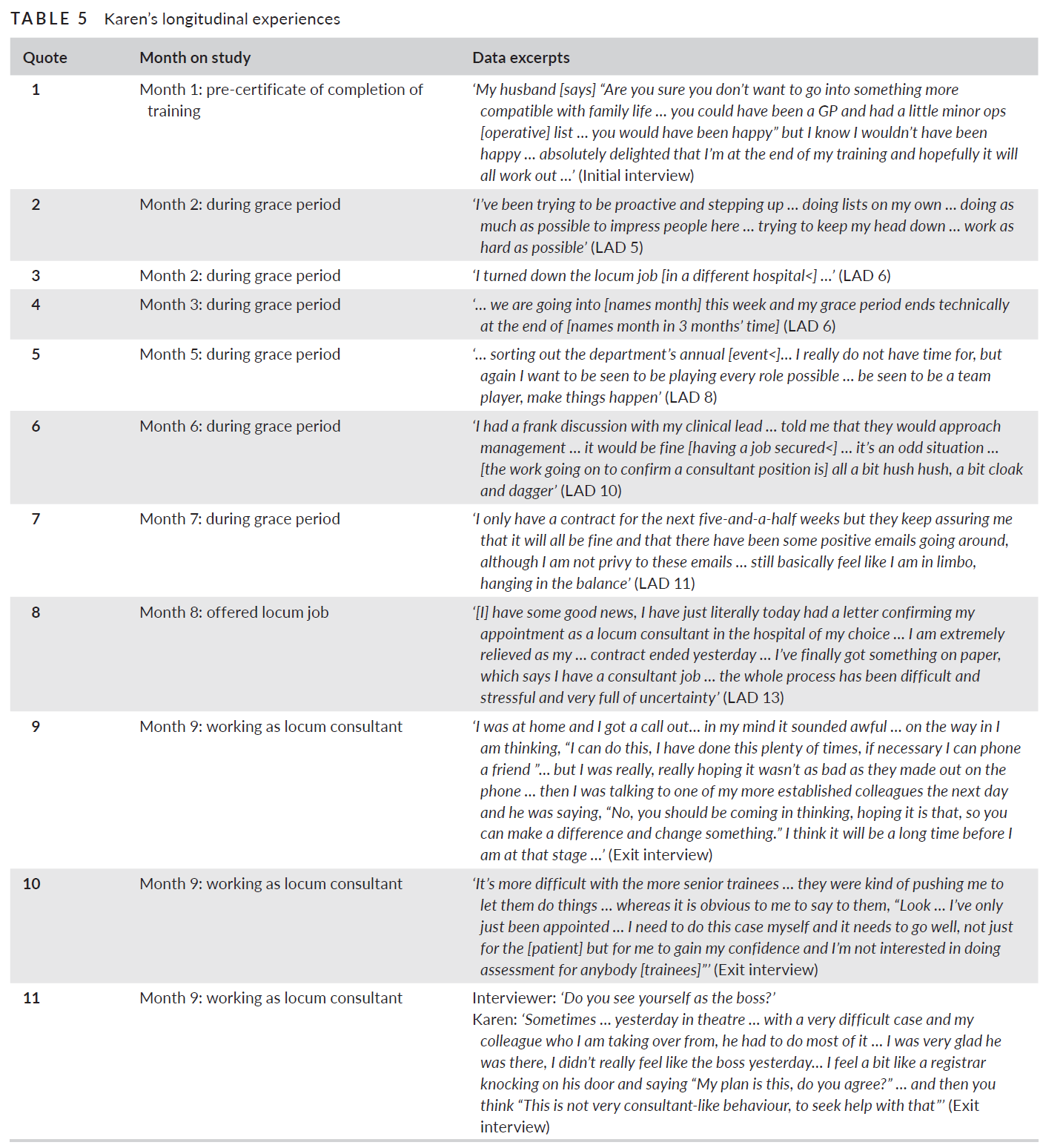

카렌이 연구를 시작한 지 두 달째 되던 해, 그녀는 CCT를 받는 공식적인 의식을 거쳤다. 그녀는 그것을 '약간의 안티-클라이막스(LAD 4)'라고 묘사했고, 그녀의 훈련 병원에서의 유예 기간grace period으로 들어갔다(그림 1). 이번 유예기간 동안 카렌은 경계적이었다. 더 이상 trainee는 아니었지만, 아직 consultant도 아니었다. 이 경계 단계(시간 제한적이고 일시적) 동안, Karen은 자신을 유능하고 대학적인 사람으로 강조함으로써 미래의 컨설턴트 자신을 투영하기 위한 자신의 정체성 작업을 설명했습니다(표 5, 인용문 2, 3).

In Karen’s second month in the study, she moved through the formal ritual of receiving her CCT, which she described as ‘a slight anticlimax’ (LAD 4) and into her grace period at her training hospital (Figure 1). Through this grace period, Karen was liminal; she was no longer a trainee, but she was not yet a consultant. During this liminal phase (time-bound and thus temporary), Karen described her identity work to project her future consultant self through emphasising herself as competent and collegiate (Table 5, Quotes 2 and 3).

카렌이 이 유예 기간을 거치면서, 그녀의 어조는 리미나로서의 불확실성을 강조하기 위해 바뀌었다. 카렌은 자신이 유예기간에 갇혔으며 컨설턴트로서의 일을 제안하기 위해 (높은 지위의) 다른 사람들에게 완전히 의존하고 있다고 자신을 표현했다.

As Karen moved through this grace period, the tone of her LADs shifted to emphasise her uncertainty as a liminar (and its associated stresses). Karen presented herself as trapped in her grace period and as having complete reliance on others (of higher status) to offer her work as a consultant.

이 기간 동안 카렌은 자신의 유예 기간이 끝날 때까지의 기간에 대해 모든 일기에서 언급했다(표 5, 인용문 4). 또한, 카렌의 정체성 작업은 가속화되었습니다. 예를 들어, 그녀는 자신이 팀 플레이어이며 일을 완수하는 리더임을 보여줄 수 있는 기회로 보았기 때문에 연례 직원 이벤트를 이끌겠다고 자원했습니다(예: 시간이 제한에도 불구하고). 게다가 카렌은 자신의 일기에서 자신의 훈련 환경에서 컨설턴트 자리를 확보할 수 있는 가능성에 대해 많은 대화를 나누었다고 보고했다.

During this, Karen remarked in every diary on how long it was until the end of her grace period (Table 5, Quote 4). Additionally, Karen’s identity work accelerated; for example, she volunteered to lead an annual staff event (despite having limited time) because she saw this as an opportunity to show herself to be a team player and a leader who gets things done (Table 5, Quote 5). Furthermore, Karen reported in her diaries numerous conversations about the possibility of securing a consultant position in her training setting.

카렌의 정체성 작업을 볼 때, 카렌이 (스스로를) 그 부서 내에서 '컨설턴트 의사'로 주장하였음을 볼 수 있는데, 이 주장은 의사결정 과정에서 중요한 다른 이해관계자들에 의해 인정되고 있었다(표 5, 인용문 6). 카렌은 일자리를 찾기 위한 다른 사람들의 불확실한 '망토와 단도' 성격으로 묘사된 것과 씨름했다. 정보에 부분적으로만 접근할 수 있었던 그녀는 정보를 공유하는 데 다른 사람들에게 의존했고, 선임 컨설턴트로부터 중요한 리더십 정체성 부여를 거절당했음이 틀림없었다(표 5, 견적 7).

In terms of her identity work in her audio-diaries, we can see Karen’s claims as ‘consultant doctor’ within that unit, which were being acknowledged by other stakeholders important in the decision-making process (Table 5, Quote 6). Karen struggled with what she described as the uncertain ‘cloak and dagger’ nature of others’ attempts to find her a job. Having only partial access to information, she relied on others to share information, and was arguably denied important leadership identity grants from senior consultants (Table 5, Quote 7).

마침내, 다행스럽게도, 그녀의 유예 기간이 끝난 다음날 그녀는 안식년을 보내는 또 다른 컨설턴트의 자리를 대신할 하숙 컨설턴트 자리를 제안받았다. 이것은 캐런이 새로운 컨설턴트 일을 시작하는 것과 그녀가 대신할 사람의 퇴사 사이에 겹치는 것을 의미했다. 카렌은 이 소식에 의기양양했지만 일기장에서 유예기간이 얼마나 스트레스가 많았는지 되새겨 보았다(표 5, 인용문 8).

Finally, and much to Karen’s relief, the day after her grace period ended she was offered a job as a locum consultant, covering for another consultant who was going on sabbatical. This meant that there was an overlap between Karen’s starting of her new consultant job and the leaving of the individual she was replacing. In her diary entry, although elated by this news, Karen reflected back on how stressful the grace period had been (Table 5, Quote 8).

3.4.2 | 카렌은 경계성을 점유하였다: 컨설턴트가 되지만 아직 컨설턴트가 되지 않음

3.4.2 | Karen occupies liminality: Being a consultant but not yet becoming a consultant

새로운 컨설턴트 역할을 시작한 후, 카렌은 한 달 동안 오디오 일기를 제출하지 않았다. 다음 일기에서 그녀는 컨설턴트로서 첫 경험을 되새겼다. 카렌의 정체성 작업은 그녀가 유능하고 팀플레이어이며 리더라는 것을 입증하는 일에서 '컨설턴트라고 불리는 것이 마치 거짓말을 하는 것 같음'를 느끼고, 다른 사람들이 자신에게 컨설턴트 신분을 부여하는 것을 거부하였다. 실제로, 그녀는 [간단한 환자를 맡고 싶다는 자신의 희망]과 [복잡한 환자를 맡아서 변화를 일어켜주길 바라는 동료의 신념]을 대조했다. 따라서 우리는 그녀가 다른 사람이 부여하는 컨설턴트 정체성을 거절하는 것을 목격하였으며, 카렌은 스스로 이 정체성을 주장할 때 까지는 시간이 필요하다고 말한다(표 5, 인용구 9).

After starting her new consultant role, Karen did not submit an audio-diary for a month. In her next diary, she reflected on her first experiences as a consultant on call. Karen’s identity work shifted in emphasis from working to demonstrate that she was competent, a team player and a leader (as discussed previously) to someone who ‘felt a bit of a fraud being called the consultant’ and rejected others’ grants of her new consultant identity (LAD 15, Month 9). Indeed, she contrasted her hopes for simple cases when on call with her colleague’s beliefs that she should be hoping for complicated cases so that she could make a difference. We therefore see her rejecting others’ granting of her consultant identity, stating that she requires time to claim this identity for herself (Table 5, Quote 9).

카렌은 직장 내 선배 trainee들과의 관계와 컨설턴트가 되는 데 내재된 교육자 역할에 자신이 발을 들여놓을 것이라는 기대감에 대해서도 이야기했다. 캐런은 퇴사 인터뷰에서, 현재 다른 사람이 자신에게 [교육자-컨설턴트 정체성]을 부여하는 것을 거부하고 있으며, 자신의 외과적 자신감과 전문지식을 키우기 위해 시니어 수련생들과 어려운 수술 사례를 놓고 경쟁하고 있다고 설명했습니다(표 5, 인용문 10).

Karen also talked about her relationships with senior trainees within the workplace and the senior trainees expectations that she would step into the educator role inherent in being a consultant. In her exit interview, Karen simultaneously claimed a learner-trainee identity and rejected others’ grants of her now educator-consultant identity, describing herself as in competition with her senior trainees for difficult theatre cases in order to develop her own surgical confidence and expertise (Table 5, Quote 10).

마지막으로, [자기 자신]과 [그녀가 대신하는 동료] 간의 오버랩은 캐런이 직장 내에서 자신의 위치에 대해 느끼는 감정에 영향을 미치는 것으로 보였습니다. 카랜은 [점유적 경계성] 상태일 뿐만 아니라, 대리의사라는 지위 때문에 [영구적 경계인 상태]이기도 했다. 카렌은 이러한 중복된 지원에 안도감을 표시했다. 비록 이러한 오버랩때문에 그녀는 아직도 '조금은 registrar처럼 느꼈다'라고 하지만, registrar처럼 행동해서는 안 되었고, 따라서 self-imposed occupation of liminality에 대한 불안을 보였다.

Finally, the overlap between herself and the colleague she was replacing seemed to affect how Karen felt about her position within the workplace. As well as occupying liminality here, she was also a perpetual liminar as a result of her locum status. Karen expressed relief in the support this overlap provided. Although this overlap meant that she still felt ‘a bit like a registrar,' she felt she should not be behaving like a registrar, thus indicating her anxieties about her self-imposed occupation of liminality (Table 5, Quote 11).

4 | 토론

4 | DISCUSSION

우리는 훈련된 전환 과정을 통해 의사들에 의해 서술된 한계적 경험을 탐구했다. 첫 번째 연구 질문에 답한 결과, 참가자들은 세 가지 방법으로 한계성을 경험했다는 것을 알게 되었습니다.

- 첫째, 가장 많은 사람들이 어느 순간 [일시적 경계성]을 경험했다. 정체성 작업을 통해 참가자들은 이러한 또는 그녀의 새로운 정체성으로의 전환을 촉진하기 위해 자기 성찰에 참여하고 과거, 현재, 미래의 자신을 고려하며, 종종 한계에서 벗어나기 위해 타인의 '컨설턴트' 정체성 부여에 의존합니다.

- 둘째, 일부 의사들은 이중 역할 속에서 지속적인 중간 관계in-betweenness를 겪으며, 즉 [영속적 경계성]을 경험했음을 시사한다.23 참가자들은 상황별로 그리고 사회적으로 관련성을 갖기 위해 정체성 작업을 사용하는 것으로 보였으며, 지속적으로 정체성을 전환함으로써 경쟁하는 충성심과 요구에 대응하는 경계선 브리콜러가 되었다.예를 들어, 임상에서 학술에 이르기까지).

- 셋째, 이것은 리미널리티에 대한 이론적 개념에 있어 새로운 것으로, 개인들은 때때로 경계성의 적극적인 창조와 유지를 통해 [경계성을 의도적으로 점유]하곤 했다. 예를 들어, 의사들은 훈련된 의사와 훈련된 의사 사이의 경계 공간을 의도적으로 차지하기 위해 [훈련된 신임의사trained doctor 정체성이 부여되는 것을 거부]하는 정체성 작업을 수행하였다. 우리는 일시적 경계성이나 영구적 정체성이 외부적으로 부여되는 것external imposition과는 달리, 개인이 [경계인liminar]이 되는 것을 적극적으로 선택할 수 있으며, 이에 따라 자신의 리미널리티에 대한 행위자성과 통제권을 행사할 것을 제안한다.

We explored liminal experiences narrated by doctors across traineetrained transitions. Answering our first research question, we found that participants experienced liminality in three ways.

- First, most experienced temporary liminality at some point. Through identity work, participants engaged in self-reflection and considered past, present and future selves in order to expedite shifts towards this or her new identity, often relying on ‘consultant’ identity grants from others to move them out of liminality. 26

- Second, our findings suggest that some doctors experienced perpetual liminality, undergoing enduring in-betweenness through dual roles.23 Participants were seen to use identity work to make themselves contextually and socially relevant, becoming boundary bricoleurs responding to competing loyalties and demands by continuously switching identities (eg, from clinician to academic).23,32–35

- Third, and novel to theoretical notions of liminality, individuals would sometimes purposely occupy liminality through its active creation and maintenance. For example, doctors would engage in identity work to reject grants of his or her new trained doctor identities in order to purposely occupy the liminal space between trainee and trained doctor. We suggest that, in a manner contrary to the external imposition of temporary and perpetual liminality, individuals can and do actively choose to be liminars, thereby exerting agency and control over his or her own liminality.

두 번째 연구 질문의 관점에서, [하나의 전문적 정체성(예: 수련 의사)]에서 [다른 전문적 정체성(예: 훈련된 의사)]으로 정체성이 선형적으로 진행된다는 것은, 지나치게 경계성을 단순화하여 개념화한 것임을 밝혀냈다. 실제로, 종단적 데이터셋 전체에 걸친 개인의 경험에 대한 시간적 분석 결과, 참가자들이 [항상 리미날 단계를 통해 선형으로 진행되지는 않는다는 점]에 주목했다. Karen의 경험이 보여주듯이, 맥락, 관계(대인관계와 조직관계 모두)와 시스템은 종종 이리저리로 오락가락하는 우리의 참가자들에 의해 [주장되고 부여된claimed by, and granted to 직업적 정체성]에 영향을 주었고, 따라서 항상 훈련된 의사 정체성으로 곧바로directly 진척되지는 않았습니다.

In terms of our second research question, our analysis revealed that a conceptualisation of liminality as a linear progression from one professional identity (eg, trainee doctor) to another (eg, trained doctor) is overly simplistic. Indeed, through our temporal analysis of individuals’ experiences across the longitudinal dataset, we noted that participants did not always proceed in a linear manner through the liminal phase. As Karen’s experiences illustrate, context, relationships (both interpersonal and organisational) and systems also influenced the professional identities claimed by, and granted to, our participants, which often fluctuated from one diary to the next, and thus did not always progress directly towards a trained doctor identity.

[왜 사람들이 경계성을 점유하기로 선택했는지]에 대해서, 우리는 [어떻게 transition이 개념화되는가]를 생각해볼 필요가 있다. Jindal-Snape는 이행transition을 다차원적(다차원적 및 다차원적 전환 이론)으로 간주하며, 개인의 삶의 한 맥락(예: 새로운 직업)에서의 전환이 다른 맥락(예: 홈 무브)에서의 전환을 트리거한다고 보았다.4 의사들의 직업 전환에 대한 연구는 이러한 개념적 사고와 일치하며, 그러한 과도기적인 단계들을 [복잡하고 종종 비선형적]이라고 파악한다.5-10 When we consider why people might choose to occupy liminality, we need to return to how transitions are conceptualised. Jindal-Snape considers transitions as multiple and multidimensional (multiple and multidimensional transitions theory), with transitions in one context of an individual’s life (eg, a new job) triggering transitions in other contexts (eg, a home move).4 Research on doctors’ career transitions aligns with this conceptual thinking, identifying such transitional phases as complex and often non-linear.5-10

호이어와 슈타이어트는 커리어의 변화기간에 사람들은 때때로 [일관성]과 [모호함]에 대한 상반된 욕구를 가지고 있다고 제안한다. 여기에는 불안과 상실감이 끼어들고, 개개인은 그러한 감정에 방어적인 반응을 보인다. [경계성 공간]은 이러한 감정에 대응하기 위하여 개인이 머물 수 있는 장소를 나타낸다고 할 수 있다. 실제로 [경계성 공간]은 중요한 다중 전환의 복잡성을 경험하면서 [개인의 성찰과 계획에 안전한 공간]이 될 수 있다. 우리의 종적 사례를 사용하여 이 점을 설명하기 위해, 카렌은 자신의 [경계성 공간]을 컨설턴트로 일했던 초기 경험과 이 새로운 컨설턴트 정체성에 익숙해진 경험을 되새기는데 사용했습니다. 따라서, [경계성 공간]을 점유하는 것은 (연구참여자들이) 자신의 정체성을 발전시킬 수 있는 시간을 가질 수 있게 했다.

Hoyer and Steyaert suggest that during career changes, individuals sometimes have conflicting desires for coherence and ambiguity, which can be punctuated by feelings of anxiety and loss, with individuals developing defensive responses to such feelings.28 We suggest, therefore, that liminal spaces can come to represent places in which individuals can dwell to respond to these feelings. Indeed, liminal spaces can become safe spaces for individuals’ reflection and planning as he or she experience the complexity of significant multiple transitions. To illustrate this point using our longitudinal case, Karen used her liminal space to reflect on her early experiences of being a consultant and getting used to this new consultant identity. Therefore, we argue that occupying of liminal spaces, as our data illustrate, allowed our participants time to make sense of his or her developing identities.

4.1 | 과도기 및 한계성 문헌에 대한 기여

4.1 | Contribution to the literature on transitions and liminality

요약하자면, 이 연구는 수련생으로 전환되는 동안 의사들이 겪었던 종말적 경험을 종적으로 탐구한 최초의 연구입니다. 또한, 우리의 연구 결과는 [경계성 점유]에 대한 개념을 추가하여 경계성에 대한 보다 광범위한 문헌에 새로운 기여를 한다. [점유적 경계성occupying liminality]는 개개인이 새로운 경험을 성찰하고 이해하여 경계적 정체성을 능동적으로 유지할 수 있는 안전한 공간이다.

To summarise, this study is the first of its kind to explore longitudinally the liminal experiences of doctors during trainee-trained transitions. Furthermore, our findings make a novel contribution to the wider literature on liminality23,35 by adding this notion of occupying liminality, whereby individuals actively maintain liminal identities as safe spaces in which to reflect and make sense of new experiences.

4.2 | 방법론적 강점과 한계

4.2 | Methodological strengths and limitations

우리의 연구는 다양한 방법론적 강점을 가지고 있다.

- 첫째, 우리의 정성적 데이터는 비교적 크고 다양한 표본(예: 성별 및 전문성)에서 방대한 종적 데이터(인터뷰 및 다이어리)를 수집했기 때문에 충분한 정보력을 가지고 있으며, 이는 연구 결과가 다른 영국 의사들에게 전달될 가능성을 증가시킨다.50

- 둘째, 이 연구의 세로적 성격은 또한 시간이 지남에 따라 참가자들의 독특한 경험을 탐구할 수 있게 해주었습니다. 실제로, 일기는 참가자들이 성찰을 위한 안전한 공간(그리고 어쩌면 그 자체로 한계 공간)을 확보할 수 있는 중심 메커니즘이 되었다. 이는 자신의 전환과 관련된 생각과 느낌을 공유하고 다시 볼 수 있는 영역입니다.

- 셋째, 다이어리 내에서 수집된 데이터는 현재의 생각과 감정이었고, 따라서 인터뷰, 특히 사건이 발생한 지 오래 후에 수행된 인터뷰에서는 이러한 것들이 자주 있기 때문에 기억에 의해 필터링되지 않았다.

- 넷째, 출구면접을 포함함으로써 우리는 참가자들과 함께 다이어리로 돌아갈 수 있었고, 그들은 시간이 지남에 따라 경험을 명확히 하고 확장할 수 있었다.

- 마지막으로, 데이터 분석에 대한 팀 기반 접근방식은 엄격함과 반사성을 장려했다.52 실제로 모든 연구자(LG, CER, DJ-S)가 여성이지만, 우리의 다양한 배경(예: 임상, 심리학, 교육 등)은 분석에 다양성을 가져와서 데이터에 대한 보다 다면적인 해석으로 이어졌다.53

Our study has various methodological strengths.

- First, our qualitative data have sufficient information power because we collected voluminous longitudinal data (interviews and diaries) from a relatively large and diverse sample (eg, in terms of gender and specialty), which increases the potential transferability of the findings to other UK doctors.50

- Second, the longitudinal nature of this study also allowed us to explore participants’ unique experiences over time.46,47 Indeed, the diaries became a central mechanism through which participants were able to secure a safe space for reflection (and possibly a liminal space in itself), in which he or she could share (and revisit) his or her thoughts and feelings pertaining to his or her transitions.8

- Third, the data collected within the diaries were current thoughts and feelings, and therefore were not filtered by memory as these so often are in interviews, particularly those conducted long after events have taken place.46,47

- Fourth, the inclusion of exit interviews allowed us to return to the diaries with participants, enabling them to clarify and expand on his or her experience over time.46

- Finally, our team-based approach to data analysis encouraged rigour and reflexivity.52 Indeed, although all of the researchers (LG, CER and DJ-S) are female, our diverse backgrounds (eg, clinical, psychology, education, etc.) meant that we brought diversity to the analysis, leading to a more multifaceted interpretation of the data.53

4.3 | 교육 실천에 미치는 영향

4.3 | Implications for education practice

우리의 연구 결과는 [의사들이 중요한 커리어 전환 동안 복잡하고 종종 비선형적인 방법으로 경계성을 경험할 것]이라는 것을 인식할 필요가 있음을 강조한다. 따라서 우리의 연구 결과는 이행 중in transition인 개인을 지원하는 개인화된 접근법에 우선순위를 부여할 것을 시사한다.8 실제로, 데이터의 사례 연구는 전환 경험에 대한 공개 토론을 용이하게 하기 위해 학습자와 교육자에게 한계성의 다양한 측면을 설명하는 데 도움이 될 수 있습니다.

Our findings emphasise a need to recognise that doctors will experience liminality in complex and often non-linear ways during significant career transitions. Our findings suggest therefore that priority be given to personalised approaches to supporting individuals in transitions.8 Indeed, case studies from our data could be used for teaching purposes to help explain the different facets of liminality to learners and educators in order to facilitate open discussion about transition experiences.

따라서 의사들이 경험하고 직업 여정 동안 적극적으로 점유할 수 있는 리미널리티에 대한 준비와 수용도를 높여 수련생과 트레이너 모두 리미너 이전과 수련생이 리미너일 때 모든 우려를 성찰하고 표현하는 기회로 활용해야 한다. 예를 들어 멘토, 동료 및 경험이 풍부한 동료와의 지원 대화를 통해 이를 달성할 수 있습니다.

Increased preparation for and acceptance of the liminality doctors will experience and may actively occupy during his or her career journey should thus be developed amongst trainees and trainers alike and used as an opportunity to reflect on and articulate any concerns before and when trainees are liminars. This could be achieved through, for example, supportive conversations with mentors, peers and more experienced colleagues.

또한, (이중 또는 임시 역할을 수행하는 경우와 같이) 영구적 경계성 경험에 대한 인식을 개선하면 그러한 영구성과 여러 역할이 수반되는 책임을 관리하는 방법에 대한 멘토링 논의를 용이하게 할 수 있습니다. 복수의 전환에 적응하기 위한 경계성 점유의 가능성도 강조해야 한다. 실제로 [경계성 점유occupying liminality]는 [의료 경력 전반에 걸친 고위험적 전환에 대한 반응]으로써, 조직과 시스템이 인식하고 지원해야 할 사항이다. 더 계획적이고 지지적인 접근법은 의사들이 한계 경험을 긍정적으로 활용하고 동시에 어떤 도전도 헤쳐나갈 수 있도록 해야 한다.

Additionally, better awareness of perpetual liminal experiences (such as when undertaking dual or temporary roles) should facilitate mentorship discussions around how to manage such perpetuity and the responsibilities that come with multiple roles. The possibility of occupying liminality to adapt to multiple transitions shoul d also be emphasised. Indeed, occupying liminality, as a response to high-stakes transitions across medical careers, is something that organisations and systems should recognise and support. A more planned and supportive approach should allow doctors to make positive use of liminal experiences and simultaneously navigate any challenges.

4.4 | 추가 연구를 위한 의미

4.4 | Implications for further research

Med Educ. 2020 Nov;54(11):1006-1018.

doi: 10.1111/medu.14219. Epub 2020 Jun 23.

Doctors' identity transitions: Choosing to occupy a state of 'betwixt and between'

Lisi Gordon 1 2, Charlotte E Rees 2 3, Divya Jindal-Snape 4

Affiliations collapse

Affiliations

- 1Centre for Medical Education, School of Medicine, University of Dundee, Dundee, UK.

- 2Monash Centre for Scholarship in Health Education (MCSHE), Faculty of Medicine, Nursing and Health Sciences, Monash University, Clayton, Victoria, Australia.

- 3College of Science, Health, Engineering and Education (SHEE), Murdoch University, Murdoch, Western Australia, Australia.

- 4Transformative Change: Education and Life Transitions (TCELT) Research Centre, School of Education and Social Work, University of Dundee, Dundee, UK.

- PMID: 32402133

- DOI: 10.1111/medu.14219Abstract

- Context: During transitions, doctors engage in identity work to adapt to changes in multiple domains. Accompanied by this are dynamic 'liminal' phases. Definitions of liminality denote a state of being 'betwixt and between' identities. From a social constructionist perspective, being betwixt and between professional identities may either involve a sense of disrupted self, requiring identity work to move through and out of being betwixt and between (ie, temporary liminality), or refer to the experiences of temporary workers (eg, locum doctors) or those in dual roles (eg, clinician-managers) who find themselves perpetually betwixt and between professional identities (ie, perpetual liminality) and use identity work to make themselves contextually relevant. In the health care literature, liminality is conceptualised as a linear process, but this does not align with current notions of transitions that are depicted as multiple, complex and non-linear.Results: All participants experienced liminality. Our analysis enabled us to identify temporary and perpetual liminal experiences. Furthermore, fine-grained analysis of participants' identity talk enabled us to identify points in participants' journeys at which he or she rejected identity grants associated with his or her trained status and instead preferred to remain in and thus occupy liminality (ie, neither trainee nor trained doctor).

- Conclusions: This paper is the first to explore longitudinally doctors' liminal experiences through trainee-to-trained transitions. Our findings also make conceptual contributions to the health care literature, as well as the wider interdisciplinary liminality literature, by adding further layers to conceptualisations and introducing the notion of occupying liminality.

- Methods: We undertook a longitudinal narrative inquiry study using audio-diaries to explore how doctors experience liminality during trainee-to-trained transitions. In three phases, we: (a) interviewed 20 doctors about his or her trainee-to-trained transitions; (b) collected longitudinal audio-diaries from 17 doctors for 6-9 months, and (c) undertook exit interviews with these 17 doctors. Data were analysed thematically, both cross-sectionally and longitudinally, using identity work theory as an analytical lens.

- © 2020 The Authors. Medical Education published by Association for the Study of Medical Education and John Wiley & Sons Ltd.

'Articles (Medical Education) > 전문직업성(Professionalism)' 카테고리의 다른 글

| 임상술기와 지식의 학습과 전이에 있어서 감정의 역할(Acad Med, 2012) (0) | 2021.07.31 |

|---|---|

| 의과대학이라는 형상화된 세계에서 의사가 되기 전 정체성 저술하기(Perspect Med Educ, 2018) (0) | 2021.07.28 |

| 의사됨의 형상화된 세계에서 정서와 정체성(Med Educ, 2015) (0) | 2021.07.24 |

| CBME에서 성장형 마음가짐(Med Teach, 2021) (0) | 2021.07.22 |

| 보건전문직 교육에서 성장형 마음가짐 이론을 특징짓는 것에 대한 고찰(Med Educ, 2020) (0) | 2021.02.03 |