졸업후의학교육의 사회적 요구에 반응하기: 인증의 역할(BMC Med Educ, 2020)

Responsiveness to societal needs in postgraduate medical education: the role of accreditation

Ingrid Philibert1* and Danielle Blouin2

배경

Background

의료 교육 기업은 자신이 생산하는 의료 인력으로 서비스를 받을 시민에게 책임을 집니다 [1]. 적절한 규모의, 숙련된, 분산된 의료 인력이 모든 국가의 건강에 매우 중요하다. 이러한 인력의 구성과 기술은 의학 교육의 대학원 단계에서 상당 부분 결정된다. 30년 전, 세계 의료 교육 연맹(WFME)은 의료 교육의 목표가 모든 사람들의 건강을 증진시킬 의사를 생산하는 것이라고 선언했고, 의료 과학의 발전에도 불구하고 이 목표가 충족되지 못하고 있다고 언급했다[2]. 1995년, 세계보건기구(WHO)는 의과대학의 사회적 책무를 "지역, 지역 및/또는 그들이 봉사하는 국가의 우선적인 건강 문제를 해결하기 위한 방향으로 그들의 교육, 연구 및 서비스 활동을 지향할direct 의무"[3]로 정의했다. 의료 교육 및 인증 전문가는 2013년 결과 기반 인증 세계 서밋에서 사회적 책임의 중요성을 논의했습니다.각주 1

The medical education enterprise is accountable to the citizens who will be served by the physician workforce it produces [1]. An appropriately sized, skilled, and distributed physician workforce is critical to the health of any nation. The composition and skill set of this workforce is determined in significant part during the postgraduate phase of medical education. Three decades ago, the World Federation for Medical Education (WFME) declared that the aim of medical education is to produce physicians who will promote the health of all people, and noted that this aim was not being met despite progress in medical science [2]. In 1995, the World Health Organization (WHO) defined the social accountability of medical schools as “the obligation to direct their education, research and service activities towards addressing the priority health concerns of the community, region, and/or nation they serve” [3]. Medical education and accreditation experts discussed the importance of social accountability at the 2013 World Summit on Outcomes-Based Accreditation.

정상 회담 참가자는 미국, 캐나다 및 네덜란드를 포함한 여러 국가의 인증 시스템에 초점을 맞춘 광범위한 영역에서 인증의 역할에 대해 논의하였다. 이 기사에서는 대부분의 국가의 의료 시스템에서 상대적으로 분산되어 운영되는 점을 감안할 때 대학원 의학 교육의 더 실행 가능한 용어로 "사회적 대응성social reponsiveness"을 제안한다. 사회적 대응성은 "사회적 요구에 대응하는 행동 과정의 참여"로 정의되었습니다 [4].

Participants at the summit discussed the role of accreditation in a wide range of domains, focusing on the accreditation systems in different nations, including the United States, Canada, and the Netherlands. In this article, we propose “social responsiveness” as a more actionable term for postgraduate medical education, given its relatively decentralized operation in most nations’ health care systems. Social responsiveness has been defined as the “engagement in a course of actions responding to social needs” [4].

WFME와 WHO의 사회적 책임 정의에는 의료 교육 시스템이 생산하는 의료 인력의 역량에 대한 기대가 내재되어 있다. 그러나 정의의 일반적인 특성은 그것들을 대학원 의학 교육 프로그램과 기관에 대한 실행 가능한 권장사항으로 변환하는 것을 어렵게 만든다. "대응성responsiveness"이라는 용어는 정부, 의료 기관, 교육자, 전문가 및 일반인을 포함한 이해관계자가 의료 우선 순위를 집단적으로 식별해야 한다는 WHO의 기대와 일치한다[3].

Inherent in the WFME and WHO definitions of social accountability are expectations for the competencies of the physician workforce that the medical education system produces. Yet the general nature of the definitions makes it challenging to translate them into actionable recommendations for postgraduate medical education programs and institutions. The term “responsiveness” is congruent with the WHO expectation that health care priorities should be collectively identified by stakeholders, including governments, health care organizations, educators, professionals, and members of the public [3].

주 텍스트

Main text

대학원 의료교육의 사회적 대응성

Social responsiveness in postgraduate medical education

의대에 대한 사회적 책임 기대치를 논의한 이전의 논평자들과는 대조적으로, 우리는 의대 이후 의사 교육에 초점을 맞추고 PGME 시스템에서 사회적 대응성에 대한 네 가지 우선 순위를 설명한다.

- 첫 번째는 의료 인력의 규모, 전문적 혼합 및 지리적 분포가 환자 및 인구 보건 요구를 충족하기에 적절한지 확인하는 것이다[5, 6].

- 두 번째 우선 순위는 전문직 종사자가 [점점 더 다양한 인구에서 보건의 차이[8]와 보건의 사회적 결정요인[9]]을 다루면서 [접근성, 인구 보건 및 자원 관리[7]에 대한 사회적 목표]를 충족할 수 있도록 하기 위해 필요한 기술 세트skill set을 갖추는 것이다.

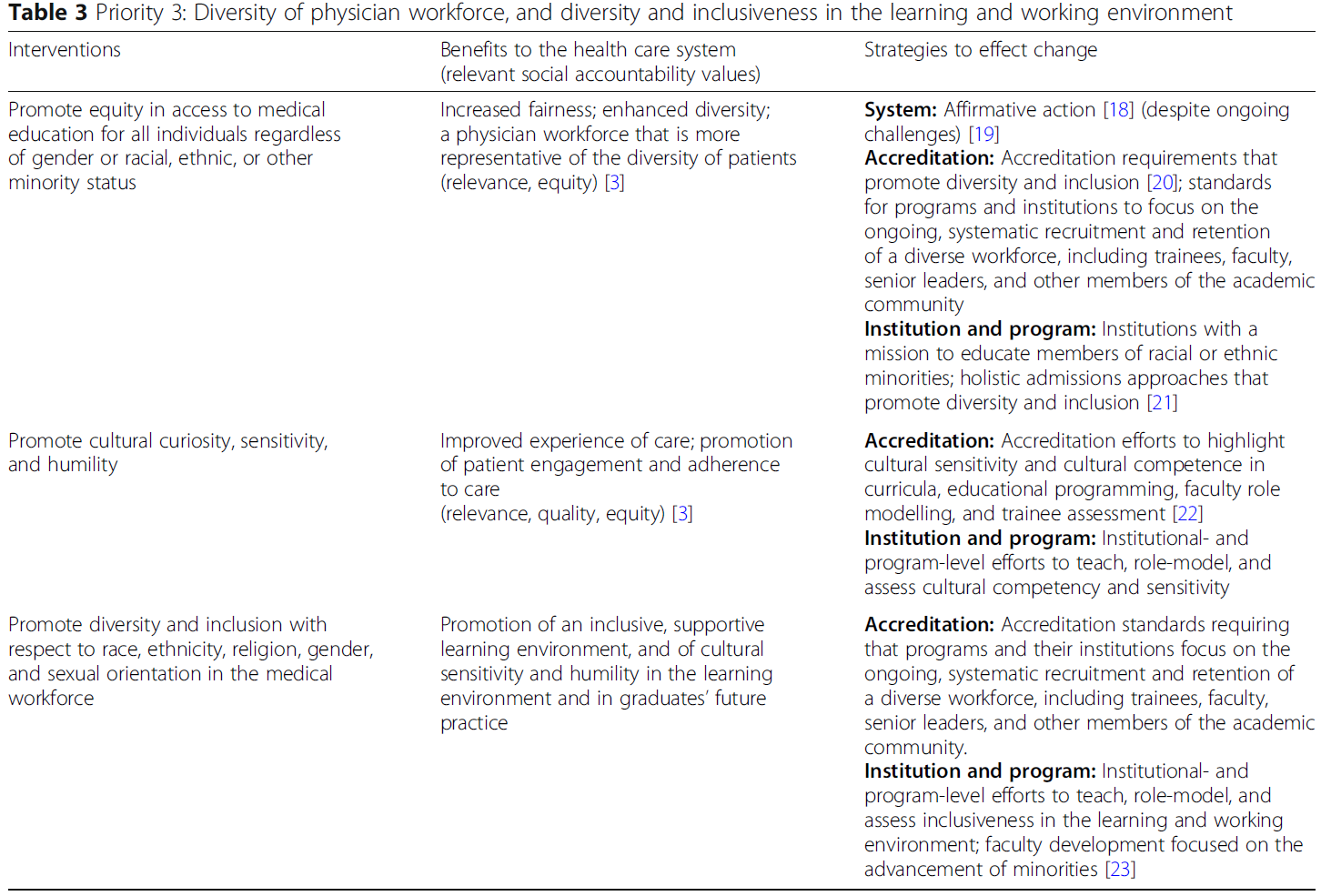

- 세 번째 우선순위는 학습 환경의 다양성과 포괄성을 향상시키는 것과 관련이 있다. 이것은 의사 노동력에서 인종, 민족 및 기타 소수민족의 표현을 증가시키고 모든 교육생을 위한 포괄적이고 지원적인 환경을 촉진하는 것을 포함한다.

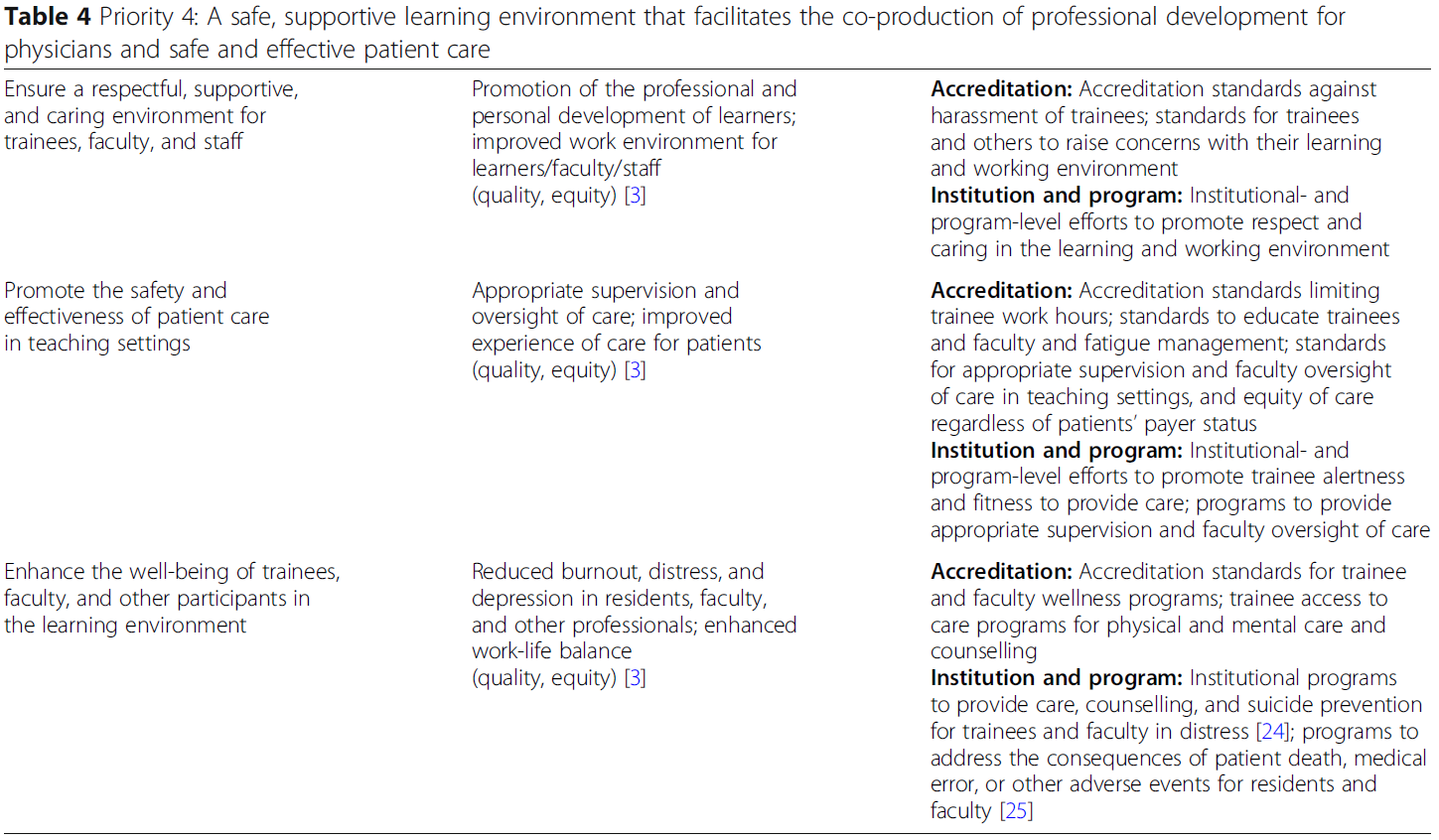

- 네 번째 우선순위는 [의사의 전문적 개발을 촉진]하는 동시에 [교육생이 진료를 배우고 참여하는 환경에서 안전하고 효과적인 care]를 제공하는 안전하고 존중하고 지지적인 학습 및 근무 환경을 확보하는 것이다.

In contrast to earlier commentators who have discussed social accountability expectations for medical schools, we focus on physician education after medical school and describe four priorities for social responsiveness in the postgraduate medical education system.

- The first pertains to ensuring that the size, specialty mix, and geographic distribution of the physician workforce is adequate to meet patient and population health needs [5, 6].

- The second priority pertains to the skill set necessary to enable the profession to meet societal goals for access, population health, and the stewardship of resources [7] while addressing health disparities [8] and the social determinants of health [9] in increasingly diverse populations.

- The third priority relates to enhancing the diversity and inclusiveness of the learning environment; this includes increasing the representation of racial, ethnic, and other minorities in the physician workforce and promoting an inclusive and supportive environment for all trainees.

- The fourth priority pertains to ensuring a safe, respectful, and supportive learning and working environment that facilitates the professional development of physicians while providing safe and effective care in settings where trainees learn and participate in care.

네 가지 우선순위에 대한 세부 사항은 표 1, 2, 3, 4에 나와 있습니다. 세 가지 우선순위는 미래의의사 노동력과 관련이 있으며, 하나는 미래의사 노동력의 전문적인 사회화를 위한 맥락을 제공하는 학습 환경과 관련이 있다. 이러한 우선 순위는 Boelen의 사회적 의무 규모를 보완하고 운영화를 촉진합니다 [4].

Detail on the four priorities is shown in Tables 1, 2, 3 and 4. Three of the priorities relate to the future physician workforce, and one to the learning environment that provides the context for the professional socialization of the future physician workforce. These priorities complement Boelen’s social obligation scale and facilitate its operationalization [4].

표 1 우선순위 1: 의료진의 적절한 규모, 전문적 혼합 및 지리적 구성

Table 1 Priority 1: Appropriate size, specialty mix, and geographic composition of the physician workforce

표 2 우선순위 2: 지속 가능한 비용으로 의료 및 인구 보건에 대한 사회적 목표를 달성하기 위한 의사 역량

Table 2 Priority 2: Physician competencies for meeting societal goals for health care and population health at a sustainable cost

표 3 우선순위 3: 의료 인력의 다양성, 학습 및 작업 환경의 다양성 및 포괄성

Table 3 Priority 3: Diversity of physician workforce, and diversity and inclusiveness in the learning and working environment

표 4 우선순위 4: 의사를 위한 전문적 개발과 안전하고 효과적인 환자 관리를 공동 제작할 수 있는 안전하고 지원적인 학습 환경

Table 4 Priority 4: A safe, supportive learning environment that facilitates the co-production of professional development for physicians and safe and effective patient care

사회적 대응 목표 충족을 위한 접근 방식

Approaches to meeting social responsiveness aims

표 1, 2, 3, 4에서 우리는 네 가지 우선 순위를 다루기 위해 시스템 수준(정부 실체와 인가자), 기관 및 프로그램 및 개인의 개입을 요약한다. 이는 인증를 많은 영역에서 사회적 책임의 지렛대로 강조한다. 우리는 1995년 WHO 문서에서 논의한 사회적 책무에 대한 네 가지 가치, 즉

- (1) 관련성(의료 교육의 목표가 그것이 봉사하는 지역사회의 요구와 목표와 일치하는 정도),

- (2) 품질(의학교육이 trainee와 graduate가 practice하는 환경 양쪽에서 모두 양질의 효과적인 케어에 기여하는 정도)

- (3) 비용 효과(의료 교육이 비용 효율적인 관리에 기여하는 정도),

- (4) 형평성(모든 사람이 의료 서비스를 이용할 수 있도록 하고, 여성과 인종, 민족 및 기타 구성원이 의료 교육을 받을 수 있도록 하는 것) [3]

In Tables 1, 2, 3 and 4, we summarize interventions at the level of the system (government entities and accreditors), the institution and program, and the individual to address the four priorities. This highlights accreditation as a lever for social accountability in many domains. We relate the social responsiveness priorities we identified to four values for social accountability discussed in a 1995 WHO document:

- (1) relevance (the degree to which the aims of medical education are congruent with the needs and aims of the communities it serves);

- (2) quality (the degree to which medical education contributes to high-quality, effective care, both in the settings where trainees participate in care and in graduates’ future practice);

- (3) cost-effectiveness (the extent to which medical education contributes to cost-effective care); and

- (4) equity (making health care available to all, and making medical education accessible to women and members of racial, ethnic, and other minorities) [3].

표 1, 2, 3, 4에 나타난 네 가지 사회적 대응성 우선순위는 새로운 것이 아니며, 여기서 요약된 많은 측면은 의과대학의 사회적 책무에 대한 합의 문서와 일치한다[26]. 그러나 사회적 책무의 차원에 대한 일반적인 인식과 상당한 합의에도 불구하고, 대학원 의학 교육에서 사회적 대응성을 폭넓게 다룬 연구는 거의 없었다. 지금까지의 연구는

- 의료 인력의 규모와 분배 최적화[27],

- 1차 진료 및 시골지역 교육 프로그램에 대한 자금 지원 강화[28],

- 학습자를 서비스 부족 환자에게 관리를 제공하는 설정에 노출시키는 서비스 학습 프로젝트

...처럼 단일 측면을 해결하기 위한 노력에 초점을 맞추었다[29]. 대학원 학습 및 작업 환경을 개선하기 위한 노력은 연습생 근무 시간 제한[30, 31]과 안전하고 효과적이며 지원적인 학습 환경을 촉진하기 위한 개입[12]에 초점을 맞추고 있다.

The four social responsiveness priorities shown in Tables 1, 2, 3 and 4 are not new, and many of the aspects summarized there are congruent with a consensus document on the social responsibility of medical schools [26]. Yet, despite a general appreciation and considerable agreement on dimensions of social accountability, few studies have broadly addressed social responsiveness in postgraduate medical education. Work to date has focused on efforts to address a single aspect, such as

- optimizing the size and distribution of the physician workforce [27],

- enhanced funding for primary care and rural training programs [28], and

- service learning projects to expose learners to settings that provide care for underserved patients [29].

Efforts to enhance the postgraduate learning and working environment have focused on trainee work hour limits [30, 31] and interventions to promote a safe, effective, and supportive learning environment [12].

- 사회적 책무성 목표를 충족하는 프로그램을 장려하기 위해 [PGME를 위한 기금을 재할당하자]는 제안[32]과 같은 개념적 수준에서 더 광범위한 개입을 위한 제안이 일반적으로 제기되었으며, 일부 논평자들은 기금 할당에 사용할 측정 기준을 권고했다[33].

- 캐나다에서는, 대학원 의학 교육의 미래를 다룬 한 단체 컨소시엄의 보고서가 의사들이 봉사하는 공공에 대한 사회적 책무성을 강조했다[34].

- 학부 의학 교육 수준에서 미국의 "사회적 책무" 지표 제안은 의과대학의 output을 졸업생이 어느 정도 비율로 일차의료나, 의료인 부족 지역에서 근무하는지, URM의 비율이 얼마인지 평가하였다. 의과대학 순위는 의과대학이 이러한 사회적 임무에 기여한 바가 상당히 다르다는 것을 보여주었다 [35].

- Suggestions for broader interventions have generally been made at the conceptual level, such as proposals in the United States to reallocate funding for graduate medical education to incentivize programs that meet social accountability aims [32], and some commentators have recommended metrics to be used in the allocation of funds [33].

- In Canada, the report of a consortium of organizations that addressed the future of postgraduate medical education emphasized the social accountability of physicians to the public they serve [34].

- At the undergraduate medical education level, a US proposal for a “social mission” metric assessed the output of medical schools as the percentage of graduates who practice primary care, work in areas affected by a shortage of health professionals, and are members of under-represented minorities; their ranking showed that medical schools vary substantially in their contribution to these social missions [35].

량 기반 PGME 시스템이 사회적 대응 목표를 충족하려면 인증 기관은 다음을 보장해야 합니다.

- 학습은 관련 역량을 강조한다

- 졸업생이 의료 접근, 인구 건강, 환자 진료 경험 향상 및 유한 의료 자원의 책임에 대한 사회적 목표를 충족할 수 있는 속성을 보유한다.

Meeting goals for social responsiveness in a competency-based postgraduate medical education system requires accrediting organizations to ensure

- that learning emphasizes relevant competencies, and

- that graduates possess the attributes to meet societal goals for health care access, population health, improved patient experience of care, and stewardship of finite health care resources [8].

미국에서는 2019년부터 시행되는 인증기준에 따라 대학원 의학 교육 프로그램이 "숙의 설계" 접근방식을 사용하여 "지원 기관의 전반적인 임무 내에서, 그들이 복무serve하는 공동체의 요구, 그리고 그들이 양성고자 하는 의사의 능력에 적합한 목표를 설정하도록 요구하고 있다"[36]. 새로운 표준에는 또한 프로그램 평가 및 개선에서 인력 다양성이 고려될 것이라는 기대도 포함되어 있다[20]. 이와 같은 표준은 의사 교육 시스템이 사회적 요구를 더 잘 충족시킬 수 있도록 하는 변화에 영향을 미치는 대학원 의학 교육의 능력을 증가시킬 것이다.

In the United States, accreditation standards that will become effective in 2019 call for postgraduate medical education programs to use a “deliberate design” approach to set aims relevant to the “needs of the communities they serve, within the overall mission of their sponsoring institution, and the capabilities of physicians they intend to graduate” [36]. The new standards also include an expectation that workforce diversity be considered in program evaluation and improvement [20]. Standards like these will increase the ability of postgraduate medical education to influence change that allows the physician education system to better meet societal needs.

사회적 기대 충족을 위한 과제 극복

Overcoming challenges to meeting societal expectations

GME의 사회적 책무성을 개선하기 위한 전략은 시간적 제약, 다른 커리큘럼 구성 요소와의 경쟁, 재정적 제한, 그리고 제도적 저항에 의해 저해될 수 있다. 인가를 통한 사회적 책임의 촉진은 인가된 프로그램과 후원 기관이 운영되는 환경의 영향을 받는 [복잡한 적응적 시스템]이라는 사실에 민감할 필요가 있다. 이는 [감독 기관으로부터 발생할 수 있는 상충적 요구]와 [의료 교육계의 다양한 이해 관계와 초점]을 충족시키는 능력을 제한시킨다. 예를 들어, 네덜란드에서, 책임성, 교육 집중, 신뢰, 역할 모델링 및 일과 삶의 균형에 관한 상출적 관점이 국가의 대학원 의학 교육 시스템의 미래에 대한 논의에서 나타났다[38].

Strategies to improve the social accountability of postgraduate medical education can be impeded by time constraints, competition with other curricular components, financial limitations, and institutional resistance. The promotion of social accountability through accreditation will need to be sensitive to the fact that accredited programs and sponsoring institutions are complex adaptive systems [37] influenced by the environments in which they operate. This constrains their ability to meet the range of potentially competing demands that arise from oversight organizations and the varying interests and foci within the medical education community. For example, in the Netherlands, competing perspectives with regard to accountability, educational focus, trust, role modelling, and work-life balance emerged in discussions about the future of the nation’s postgraduate medical education system [38].

미국과 캐나다와 같은 대부분 시장 기반 시스템에서는 의료 인력의 규모와 혼합을 최적화하려는 노력과 관련하여 추가적인 과제가 있다(표 1). 인가자는 일반적으로 인가 결정에서 인력진의 적정성 결정을 이용하지 않기 때문에 인가를 [직접 지렛대]로 사용할 수 없다[39]. 또한, 공식 커리큘럼과 학습 경험은 generalist의 실습과 소외된 모집단의 관리를 촉진할 수 있지만, 이러한 모집단의 일반의 실습과 관리를 위한 의사의 공급을 증가시키기 위한 노력은 일반의사 전문성 격하를 포함한 의료교육의 "숨겨진 커리큘럼"[40]을 해결해야 한다. 여기에는 매우 필요한 전문 분야에 대한 제너럴리스트 전공분야[41]와 재정적[42] 및 사회적[41] 보상 구조의 격하를 포함한다.

There are additional challenges with regard to efforts to optimize the size and mix of the physician workforce (Table 1) in largely market-based systems such as the United States and, to a lesser degree, Canada. Accreditation cannot be used as a direct lever, as accreditors generally are enjoined from using workforce adequacy determinations in accreditation decisions [39]. In addition, while formal curricula and learning experiences can promote generalist practice and care of underserved populations, efforts to increase the supply of physicians for generalist practice and care in these populations need to address the “hidden curriculum” [40] in medical education, including the disparagement of generalist specialties [41] and the financial [42] and societal [41] reward structure for these highly needed specialties.

세계적으로 의사들을 더 큰 자유, 더 높은 보상, 더 나은 삶의 질을 가진 국가로 이동시키거나 지역 의사들의 부족 문제를 해결하기 위한 "두뇌 유출"에 대한 우려가 있다 [43]. 2011년, WHO는 의사의 해외이주로 인해 질병 부담이 높고 이미 보건 인력의 부족에 직면하고 있는 국가에 피해를 줄 수 있다는 사실을 인식하여 보건 인력의 국제 채용에 관한 글로벌 실무 강령을 제정했다[14]. 호주와 뉴질랜드의 의사 부족 문제를 해결하기 위한 노력은 [교육 및 보건 시스템의 요소를 환자 치료 요구에 맞추는 것]이 [의사 "수입" ]보다 더 효과적이라고 제안했다 [44]. 아랍에미리트에서는 에미리트 국민이 국가와 지역에 봉사할 차세대 의사를 양성하기 위한 노력이 있습니다 [45].

Globally, there are concerns with the “brain drain” that results from the migration of physicians to nations with greater freedom, higher reimbursement, and better quality of life, or to address local physician shortages [43]. In 2011, the WHO instituted a Global Code of Practice on the International Recruitment of Health Personnel, in recognition of the fact that the out-migration of physicians may hurt nations that have a high disease burden and already face shortages in their health workforce [14]. Efforts to address physician shortages in Australia and New Zealand have suggested that aligning elements of education and health systems with patient care needs is more effective than “importing” physicians [44], and in the United Arab Emirates there are efforts to train Emirati nationals to make up the next generation of physicians to serve the nation and region [45].

GME의 사회적 요구와 기대치를 해결하는 것은 효과적인 접근 방식과 이해 관계자에 대한 홍보, 성공과 도전 탐색, 채택 또는 적응을 위한 효과적인 실천에 대한 정보 수집 및 보급을 포함한 추가 작업의 영역이다.

Addressing societal needs and expectations in postgraduate medical education is an area for additional work, including research on effective approaches and outreach to stakeholders, exploring successes and challenges, and gathering and disseminating information on effective practices for adoption or adaptation.

결론

Conclusion

대학원 의학 교육의 사회적 대응성은 시스템, 기관, 프로그램 및 개인 수준의 다양한 접근방식을 통해 달성될 수 있다. 인증은 다양한 국가 맥락과 다양한 차원의 사회적 대응성에 걸쳐 효과적일 수 있는 잠재력을 가지고 있다. 핵심 관측은 역량 기반 대학원 의학 교육 시스템에서 사회적 대응력을 충족하려면 학문이 관련 역량을 강조하고, 졸업생이 원하는 속성을 보유하도록 인가 기관이 보장해야 한다는 것이다. 이와 함께 대학원 의료교육을 후원하는 기관이 지원적이고 인문학적인 학습과 근무환경에서 안전하고 효과적인 환자진료를 제공하는 역할이 있다.

Societal responsiveness in postgraduate medical education can be achieved through a range of approaches at the system, institution, program, and individual levels. Accreditation has the potential to be effective across different national contexts and across the various dimensions of social responsiveness. A key observation is that meeting social responsiveness in a competency-based postgraduate medical education system requires accrediting organizations to ensure that learning emphasizes relevant competencies, and that graduates possess desired attributes. At the same time, there is a role for institutions that sponsor graduate medical education to provide safe and effective patient care in a supportive, humanistic learning and working environment.

BMC Med Educ. 2020 Sep 28;20(Suppl 1):309.

doi: 10.1186/s12909-020-02125-1.

Responsiveness to societal needs in postgraduate medical education: the role of accreditation

Ingrid Philibert 1, Danielle Blouin 2

Affiliations collapse

Affiliations

-

1Department of Medical Education, Frank H. Netter MD School of Medicine at Quinnipiac University, North Haven, CT, USA. ingrid.philibert@quinnipiac.edu.

-

2Faculty of Health Sciences (Department of Emergency Medicine) and Faculty of Education, Queen's University, Kingston, Ontario, Canada.

-

PMID: 32981520

-

PMCID: PMC7520978

Free PMC article

Abstract

Background: Social accountability in medical education has been defined as an obligation to direct education, research, and service activities toward the most important health concerns of communities, regions, and nations. Drawing from the results of a summit of international experts on postgraduate medical education and accreditation, we highlight the importance of local contexts in meeting societal aims and present different approaches to ensuring societal input into medical education systems around the globe.

Main text: We describe four priorities for social responsiveness that postgraduate medical education needs to address in local and regional contexts: (1) optimizing the size, specialty mix, and geographic distribution of the physician workforce; (2) ensuring graduates' competence in meeting societal goals for health care, population health, and sustainability; (3) promoting a diverse physician workforce and equitable access to graduate medical education; and (4) ensuring a safe and supportive learning environment that promotes the professional development of physicians along with safe and effective patient care in settings where trainees participate in care. We relate these priorities to the values proposed by the World Health Organization for social accountability: relevance, quality, cost-effectiveness, and equity; discuss accreditation as a lever for change; and describe existing and evolving efforts to make postgraduate medical education socially responsive.

Conclusion: Achieving social responsiveness in a competency-based postgraduate medical education system requires accrediting organizations to ensure that learning emphasizes relevant competencies in postgraduate curricula and educational experiences, and that graduates possess desired attributes. At the same time, institutions sponsoring graduate medical education need to provide safe and effective patient care, along with a supportive learning and working environment.

Keywords: Accreditation; Diversity; Equity; Postgraduate medical education; Societal accountability.

'Articles (Medical Education) > 대학의학, 조직, 리더십' 카테고리의 다른 글

| 사회적 책무성과 인증: 교육기관을 위한 새로운 프론티어(Med Educ, 2009) (0) | 2021.03.07 |

|---|---|

| 새로운 의과대학 인증평가 항목 ASK 2019(Med J Chosun Univ, 2019) (0) | 2021.03.07 |

| 의학교육 인증에서 CQI의 평가(BMC Med Educ, 2020) (0) | 2021.03.04 |

| 졸업후의학교육에서 효과적인 평가인증: 과정에서 성과로, 그리고 뒤로 (BMC Med Educ, 2020) (0) | 2021.02.28 |

| 의학교육 평가인증 시스템 설계에서 "목적적합적" 프레임워크 (BMC Med Educ, 2020) (0) | 2021.02.28 |