교수개발 만다라: 이론기반 평가를 활용한 맥락, 기전, 성과 탐색(Adv Health Sci Educ Theory Pract, 2017)

A mandala of faculty development: using theory-based evaluation to explore contexts, mechanisms and outcomes

Betty Onyura1 • Stella L. Ng1,2,3,4,5 • Lindsay R. Baker1,6 • Susan Lieff1,7 • Barbara-Ann Millar1,8 • Brenda Mori1,9

도입

Introduction

교수개발 프로그램은 교수진의 학문적 역할 수행을 지원하기 위한 전문 개발 활동을 제공한다(Centra 1978; Steinert 2014). 비록 이러한 프로그램은 현재 보건 분야에서 보편화되었지만, 장기적인 영향과 영향 질문을 해결하기 위한 기존 연구 접근 방식의 부적절성에 대한 의문이 남는다(McLeod and Steinert 2010; O'Sulivan and Irby 2011; Singh 2013).

Faculty development programs offer professional development activities intended to support faculty in performing their academic roles (Centra 1978; Steinert 2014). Although, such programs are now commonplace in the health professions, questions remain about their long-term impact, and the (in)adequacy of existing research approaches for addressing impact questions (McLeod and Steinert 2010; O’Sullivan and Irby 2011; Singh 2013).

이론 기반 평가의 가치

The value of theory-based evaluation

교수개발 프로그램 결과를 입증하는 것은 가치 있고 점점 더 의무화되는 목표이지만, [프로그램이 결과를 실현하는 메커니즘에 대한 이해]로 입증되어야 한다(Haji et al. 2013; Parker et al. 2011). 보건전문직 교육 프로그램의 변화 메커니즘을 탐구하는 최근 몇 가지 노력이 있었지만(Parker et al. 2011; Sorinola et al. 2015), 연구는 여전히 미미한 상태이며, 조사된 결과의 범위는 개별 학습에 국한되는 경향이 있다. 평가자는 종종 이러한 결과가 어떻게 나타날 수 있는지에 대한 논리적 또는 이론적으로 근거가 있는 연계를 제공하지 않은 상태에서, 결과 또는 영향에 대한 주장을 제기하려는 블랙박스(또는 입력-출력 설계) 방식의 평가를 지향하곤 한다(Stame 2004). [투입과 산출]사이에 전개되는unfold 것을 고려하지 않는다면, 평가 연구는 프로그램 작동에 대한 좁고 왜곡된 이해만을 제공할 수 있다(Chen과 Rossi 1983).

Whereas demonstrating faculty development program outcomes is a worthwhile and increasingly mandated objective, it should be corroborated by an understanding of the mechanisms by which programs realize outcomes (Haji et al. 2013; Parker et al. 2011). Though there have been a few recent efforts at exploring mechanisms of change in health professional education programming (Parker et al. 2011; Sorinola et al. 2015), research remains scant, and the scope of outcomes examined tends to be limited to individual learning. Too often, evaluators tend toward black box (or input–output design) evaluations that seek to lay claim to outcomes and/or impact without offering accompanying logical or theoretically grounded linkages as to how these outcomes may come about (Stame 2004). Without considering what unfolds between inputs and outputs, evaluation research can provide a narrowand distorted understanding of the workings of programs (Chen and Rossi 1983).

[복잡한 환경]에서 성과는 상호작용하는 또는 조절하는 효과의 다중 변수에 의존하며, 인간 추론과 행동의 복잡한 사슬, 개인과 맥락 사이의 상호 작용에 영향을 받는다(Patton 2011). 교수개발 프로그램이 다양한 결과를 발생시키거나 기여하는 방법을 이해하기 위해서는

- (1) 참가자들이 프로그램 활동과 상호작용하는 방법과

- (2) 이러한 상호작용이 연습 상황에 어떻게 영향을 미치는가

...에 대한 통합적 이해를 개발하는 평가 전략을 채택할 필요가 있다.

In complex environments, outcomes are reliant upon multiple variables with interacting or moderating effects, and are influenced by complex chains of human reasoning and action, and interplays between individuals and contexts (Patton 2011). In order to understand how faculty development programs generate or contribute to various outcomes, one needs to adopt evaluative strategies that develop integrated understanding of

- (1) how participants interact with program activities and

- (2) how those interactions influence practice contexts.

개념적 프레임워크

Conceptual frameworks

[이론 기반 평가]는 일반적으로 사회 프로그램이 어떻게 변화를 만들어내는지에 대한 개념적 기초를 탐구하는 데 초점을 맞춘 평가 접근 방식을 설명한다. (Blamey and Mackenzy 2007; Stame 2004) [현실주의적]이고 [이론 중심적]인 평가 접근방식을 모두 포함한다.

Theory-based evaluation describes a family of evaluation approaches generally focused on exploring the conceptual underpinnings of how social programs work to produce change. (Blamey and Mackenzie 2007; Stame 2004). It includes both realist and theory-driven evaluation approaches,

[현실주의Realist 평가]는 프로그램을 [개별 행위자와 사회 구조 사이에 지속적인 상호 작용이 있는 사회적 시스템]으로 본다(파우슨과 틸리 1997). [변화]는 구조와 행위자의 산물로 간주되며, 과제는 어떤 상황에서 어떤 것이, 누구에게, 어떤 상황에서, 그리고 왜 그런지 결정하는 것이다(파우슨과 틸리 1997). 이것을 지지하는 사람들은 프로그램 자체가 변화를 일으키는 것이 아니라, (프로그램은) 변화를 위한 자원과 기회를 도입한다고 주장한다. 프로그램에 노출되었을 때, 능력과 맥락에 따라 특정 메커니즘을 활성화하고 변화를 일으키는 것은 사람들이다(McEvoy and Richards 2003; Pawson and Tilley 1997). 따라서, 중심적인 명제는 생성 메커니즘과 유용한 컨텍스트가 주어진다면 다음과 같은 특정 결과를 관찰할 수 있다는 것이다.

Realist evaluation views programsas social systems in which there is a constant interplay between individual agency and social structures (Pawson and Tilley 1997). Change is viewed as a product of structure and agency, and the task is to determine what works, for whom, in what circumstances, andwhy (Pawson and Tilley 1997). Proponents contend that programs, in themselves, do notcreate change but, rather, introduce resources and opportunities for change; it is peoplewho, when exposed to programs, activate certain mechanisms and create change,depending on their capacity and context (McEvoy and Richards 2003; Pawson and Tilley1997). Thus, the central proposition is that given a generative mechanism and a conducivecontext, one can expect to observe specific outcomes:

컨텍스트(C) + 메커니즘(M) + 결과(O)

Context (C)+Mechanism (M) + Outcome (O)

다양한 CMO 순열은 한 프로그램(Astbury 2013)에 존재할 수 있으며 메커니즘은 일부 컨텍스트에서는 효율적일 수 있지만 다른 프로그램에서는 효율적이지 않을 수 있다. 결과적으로, 시간이 지남에 따라 그리고 개인 전체에 걸쳐, 프로그램은 혼합된 결과를 낳을 수 있다. [현실주의 평가자]는 단순히 별개의 결과를 식별하는 대신, 다양한 결과 패턴이 생성되는 방법과 이유를 이해하려고 한다(Astbury 2013).

Diverse CMO permutations can exist in any one program (Astbury 2013) and mechanisms may be efficacious in some contexts, but not in others. Consequently, over time and across individuals, a program can produce mixed outcomes. Rather than merely identifying discrete outcomes, realist evaluators seek to understand how and why various outcome patterns are generated (Astbury 2013).

[이론 중심 평가] 접근 방식은 또한 프로그램 입력과 관찰된 결과 사이에 발생하는 변환 프로세스의 조사를 요구한다(Chen과 Rossi 1983, 1989, 1992). 이 접근법에서 평가자는 [프로그램이 가질 것으로 예상되는 효과를 적절히 예측하고 설명할 수 있는] 다양한 분야(예: 사회학, 심리학, 미시경제학)로부터 현존하는 사회과학 이론을 도출해야 한다. 프로그램 활동은 단기(근접) 결과에서 장기(원격) 결과(서부 및 아이켄 1997)에 이르기까지 시간 경사를 따라 펼쳐지는 효과를 가진 것으로 추정된다. 궁극적으로, 평가자의 역할은 다음과 같다.

- 주어진 프로그램이 어떻게 다양한 장단기 결과를 생성하기 위한 다양한 메커니즘을 자극하는지spur에 대한 일관된 설명account을 개념화하는 것

- 특정 프로그램이 작동하는 방식에 대한 타당하고 방어 가능한 모델을 구축하는 것

The theory-driven evaluation approach also demands examination of the transformational processes that occur between program inputs and observed outcomes (Chen and Rossi 1983, 1989, 1992). In this approach, evaluators are urged to draw upon extant social science theories from various disciplines (e.g., sociology, psychology, microeconomics) that can adequately anticipate and explain the effects that programs are expected to have. Programactivities are presumed to have effects that unfold along a temporal gradient, from short term (proximal) outcomes, to longer-term (distal) outcomes (West and Aiken 1997). Ultimately, the evaluator’s role is to

- conceptualize a coherent account how of a given program spurs various mechanisms to generate various short- and long- term outcomes (Rogers et al. 2000), or

- construct a plausible and defensible model of how a given program works (Chen and Rossi 1983).

이 계정/모델은 프로그램이 다루려고 하는 문제에 대한 [현존하는 사회과학 연구]에 기초해야 한다(Chen과 Rossi 1992). 경험적으로 기초가 된 사회과학 이론이 개념화된 연계를 지원하는 경우, 프로그램의 효과에 대한 증거가 있다.

This account/model should be grounded in extant social science research on the issues the program seeks to address (Chen and Rossi 1992). Where empirically grounded social science theory supports conceptualized links, there is evidence for the efficacy of the program.

현실주의 평가의 장점에도 불구하고, 적용의 도전과 주목할 만한 비평이 존재한다.

- 첫째, 구현이 어려울 수 있습니다. 현실주의의 깃발을 사용한 여러 연구가 원칙을 지키지 못합니다(Astbury 2013; Monaghan 2012).

- 둘째, 메커니즘의 개념이 종종 잘못 이해된다. 조사자들은 종종 메커니즘과 프로그램 활동을 혼동한다(Astbury and Leeuw 2010).

- 셋째, 특정 CMO 구성을 식별하는 것은 [관계를 해체하는 것]에 내재된 어려움으로 인한 방법론적 골칫거리가 될 수 있다(Astbury 2013; Davis 2005; Greenhalh 등). 2009).

- 마지막으로, 연구 결과를 보고하기 위한 원래 사양에는 C1 + M1 = O1이 포함되며, C2 + M2 = O2 등의 형태로 엄격한 가설을 표로 하는 행렬이 개발됩니다(파우슨과 틸리 1997; 파우슨 2013).

Despite the merits of realist evaluation, challenges in its application and noteworthy criticisms exist.

- First, implementation can be daunting; several studies that wield the realist banner fail to adhere to its principles (Astbury 2013; Monaghan 2012).

- Second, the concept of mechanisms is often misunderstood; investigators often conflate mechanisms with program activities (Astbury and Leeuw 2010).

- Third, identifying specific CMO configurations can be a methodological headache due to difficulties inherent in disentangling relationships, and dealing with conflicting theories (Astbury 2013; Davis 2005; Greenhalgh et al. 2009).

- Finally, original specifications for reporting findings include C1 ? M1 = O1, developing matrices that tabulate tight hypotheses in the form of C2 ? M2 = O2 etc. (Pawson and Tilley 1997; Pawson 2013).

그러나 이러한 [CMO 공식을 엄격하게 따르는 것]은

- (1) CMO 관계가 단순하고 선형적이라는 것을 무심코 암시하고

- (2) 복잡한 다중 메커니즘 상호 작용 및 연관성에 대한 인식을 제한함으로써 현실주의 평가의 바로 그 목표를 훼손할 수 있다(Astbury 2013).

However, rigid adherence to these CMO formulas may undermine the very goals of realist evaluation by

- (1) inadvertently implying that CMO relationships are simple and linear and

- (2) limiting recognition of complex multi-mechanism interactions and concatenation (Astbury 2013).

이러한 경고를 염두에 두고, 우리는 현실주의와 이론 중심 평가를 통합하는 혼합 접근법을 제안한다.

Heeding these warnings, we propose a blended approach that integrates realist and theory-driven evaluation.

방법론

Methodology

[이론 기반 평가] 방법론은 일반적으로

- (1) 이해관계자 협의,

- (2) 목표 평가 질문에 대한 데이터 수집,

- (3) 프로그램이 작동하는 방식에 대한 일관된 계정의 데이터 분석 및 개발

...을 포함한 세 단계로 분류될 수 있다.

Theory-based evaluation methodology can generally be grouped into three phases including:

- (1) stakeholder consultations,

- (2) data collection for targeted evaluation questions, and

- (3) data analysis and development of a coherent account of how the program works.

대상 프로그램 및 설정

Target program and setting

우리는 토론토에 있는 교수진 개발 센터의 교육 학자 프로그램(ESP) 내에서 개략적인 단계를 수행했다.

We conducted the outlined phases within the Education Scholars Program (ESP) at the Centre for Faculty Development in Toronto.

1단계: 임시 프로그램 논리 매핑

Phase one: mapping provisional program logic

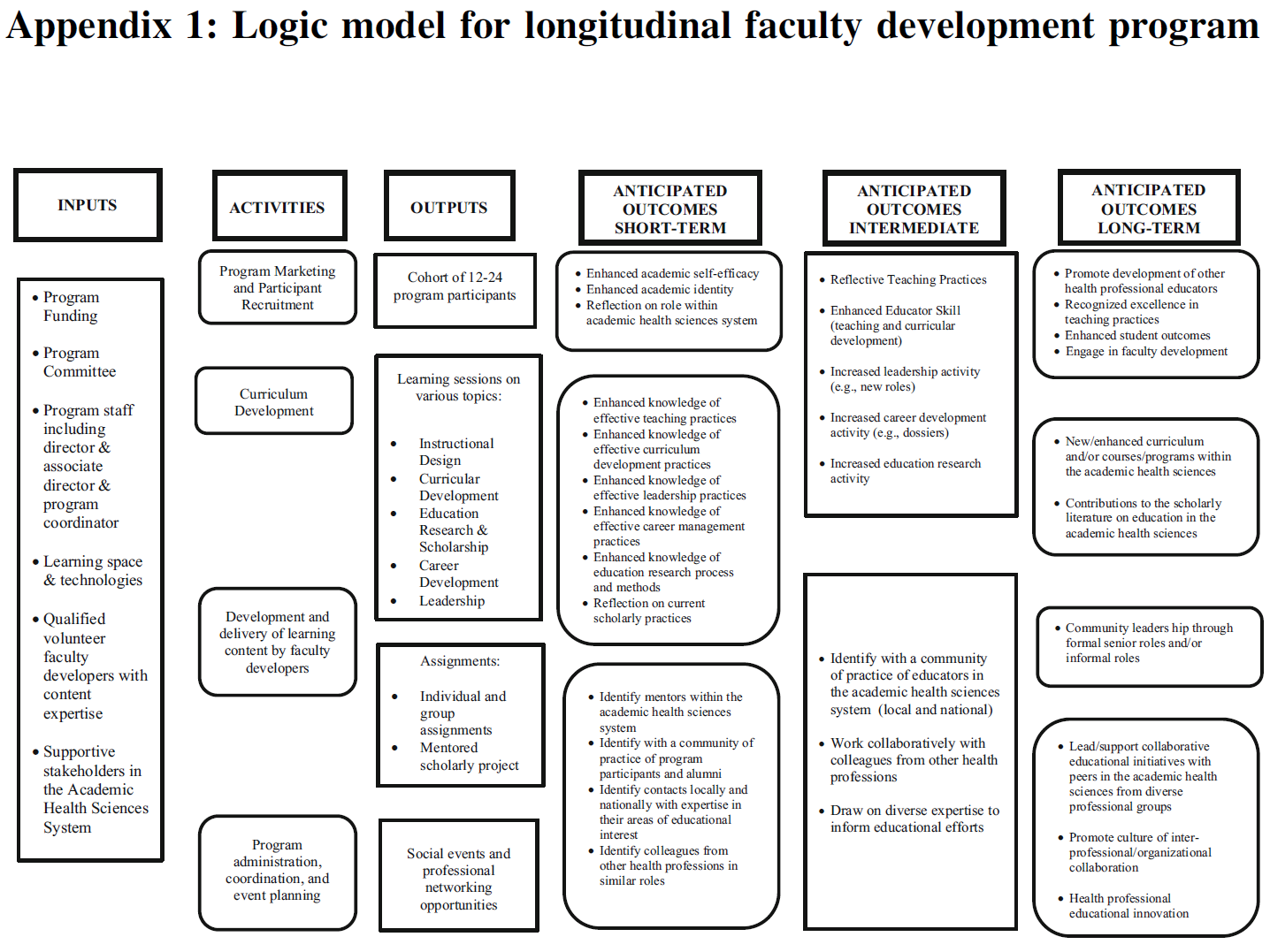

그런 다음 우리는 프로그램 활동, 출력 및 예상 결과 사이의 임시 연결을 도표로 나타내는 논리 모델을 개발했다('부록 1' 참조).

We then developed a logic model to diagrammatically represent provisional linkages between program activities, outputs, and anticipated outcomes (see ‘‘ Appendix 1’’).

2단계: 데이터 수집

Phase two: gathering data

데이터 출처에는 (a) 프로그램 참가자와 함께 하는 포커스 그룹 및 (b) 프로그램 졸업자와의 반구조적인 후속 인터뷰가 포함되었다.

Data sources included: (a) focus groups with program participants, and (b) semi-structured follow-up interviews with program graduates.

프로그램 참가자와 함께 그룹 포커스

Focus groups with program participants

질문의 표현은 해를 거듭할수록 진화했지만, (1) 커리큘럼 내용과 전달, (2) 개인적, 직업적 성장의 경험, (3) 교육 관행의 변화를 인식하는 등 세 가지 일관된 질문이 제시되었다.

Though the phrasing of questions evolved over the years, three consistent categories of questions were asked: (1) experiences of curriculumcontent and delivery, (2) experiences of personal and professional growth, and (3) perceived changes in their educational practice.

프로그램 수료자와의 반구조 인터뷰

Semi-structured interviews with program graduates

프로그램 참여가 참가자의 개인 및 전문적 결과에 어떻게 영향을 미치는지, 그리고 이러한 결과에 영향을 미치는 상황적 요인을 탐구하기 위해 반구조 인터뷰 가이드('부록 2' 참조)를 개발했다.

We developed a semi-structured interview guide (see ‘‘ Appendix 2’’), to explore how program participation impacted participants’ personal and professional outcomes, and the contextual factors that influenced these outcomes.

|

Appendix 2: Semi-structured interview protocol for longitudinal followup with program graduates

1. Please describe your current role(s) in education and what it involves.

3. Please describe any successes you have had since completing the program • What are the factors (individual or contextual) that influenced your success?

4. Who do you talk to about teaching and education? |

3단계: 데이터 분석

Phase three: data analysis

우리는 프레임워크 분석 접근법(Ritchie and Spencer 1994; Ward et al. 2013)을 채택했다. 이는 둘 다 비판적 현실주의 패러다임(Snape and Spencer 2003)에서 도출된 우리의 통합 이론 기반 평가 접근법과 잘 일치하기 때문이다. 프레임워크 분석은 연역적 요소와 귀납적 요소를 모두 포함할 수 있으며, 데이터를 관리하기 위한 구조화된 프로세스를 제공하는 동시에 정성적 조회에 관련된 유연성을 제공한다(Ward et al., 2013).

We employed a framework analysis approach (Ritchie and Spencer 1994; Ward et al. 2013) as it aligns well with our integrated theory-based evaluation approach as both derive from a critical realist paradigm(Snape and Spencer 2003). Framework analysis can include both deductive and inductive elements, and provides a structured process for managing data, while allowing for the flexibility associated with qualitative inquiry (Ward et al. 2013).

결과

Results

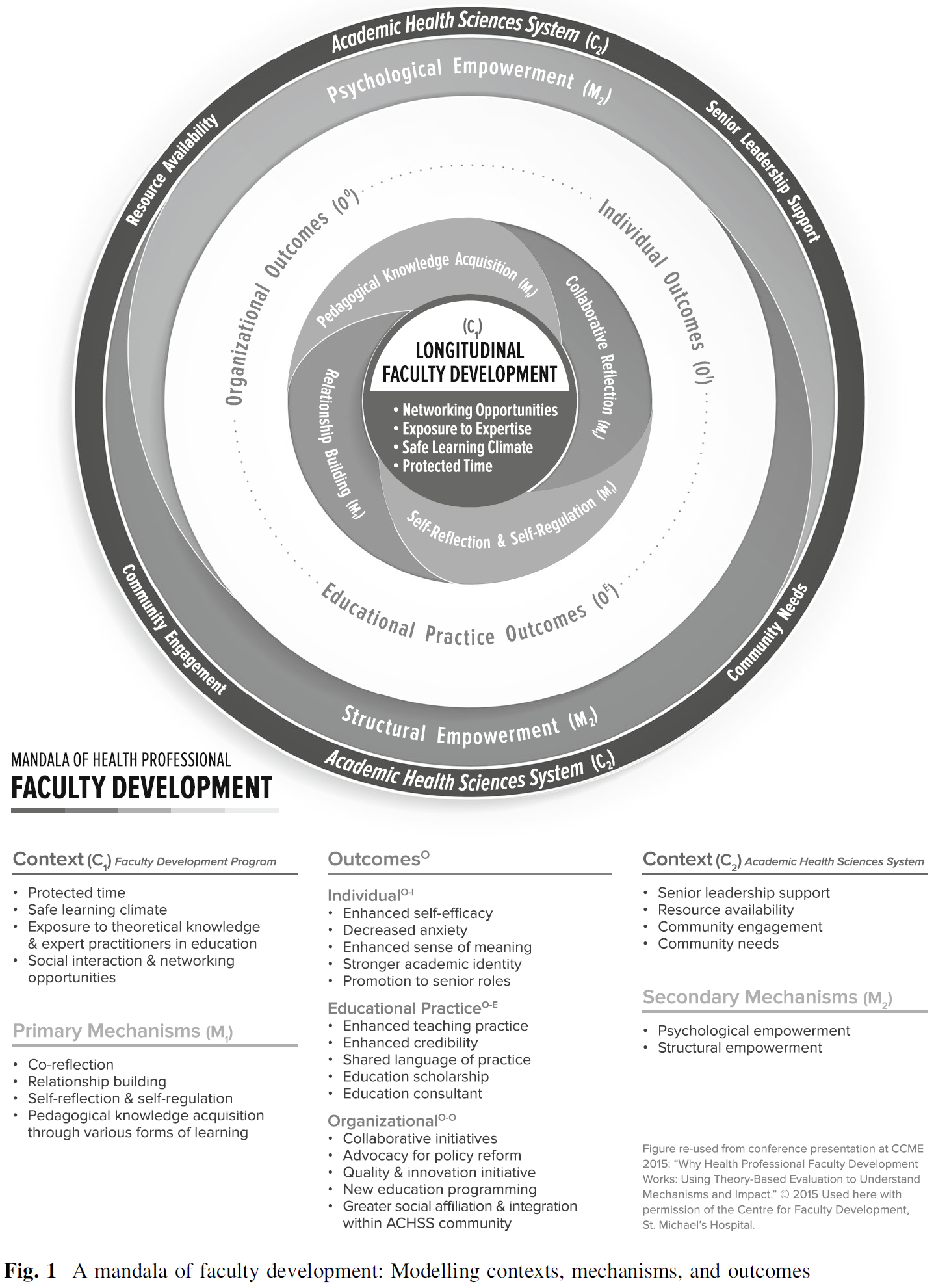

그림 1은 주어진 시스템 내에서 특별한 의미를 가진 상호 관련 요소의 원형 그림인 만달라의 개념을 바탕으로 우리의 연구 결과를 모델링한다.

Figure 1 models our findings, by drawing on the concept of a mandala, which is a circular illustration of interrelated elements with special meaning within a given system.

즉각적 프로그램 컨텍스트(C1)

Immediate program context (C1)

보호시간

Protected time

참가자들은 입학 전에 매주 4시간 반의 보호시간을 확보해야 했다. 대부분의 참가자들에게, 이것은 교육자로서 그들의 역할에 집중적인 관심을 기울이는 전례 없는 기회를 제공했다.

Participants were required to secure four and a half hours of protected time weekly, prior to admission. For most participants, this provided an unprecedented opportunity for focused attention on their roles as educators.

반대로, 임상 의무는 아니지만 부서로부터 보호 시간을 받은 참가자들은 프로그램 활동에 대한 참여를 제약하는 임상 역할과 교육 역할 사이의 지속적인 갈등을 경험했다.

Conversely, participants who received protected time from departmental but not clinical duties, experienced a sense of ongoing conflict between clinical and educational roles that constrained their engagement with program activities.

안전한 학습 환경

Safe learning climate

프로그램 참가자들은 부정적 결과에 대한 두려움 없이 아이디어 탐색, 경험 공유, 도전, 우려 등을 위한 플랫폼을 제공하는 안전한 공간이라고 인식했다.

Program participants perceived the program as a safe space that provided a platform for exploring ideas, sharing experiences, challenges, and concerns, without fear of suffering negative consequences.

사회적 상호 작용 및 네트워킹 기회

Social interaction and networking opportunities

이 프로그램은 학술 보건 과학 시스템에 걸친 보건 전문 교육자들에게 (만약 프로그램에 참여하지 않았다면 의미 있는 방법으로 관여하지 않았을) 다른 교육자들과 교류할 수 있는 기회를 제공했다.

The program provided an opportunity for health professional educators across the academic health sciences system to interact with other educators with whom they would not otherwise have engaged in a meaningful way.

교육 이론에 대한 노출 및 교육 분야에서의 경험 많은 실무자

Exposure to educational theory and experienced practitioners in education

교육과정은 참여자들을 교육에서 여러 이론적 관점에 노출시키고 관련 기술에 노출시키기 위해 고안되었다. 그것은 경험이 풍부한 촉진자와 학술적 건강 과학의 확립된 학문적 리더(및 실무자)에 의해 전달되었다.

The curriculum was designed to expose participants to multiple theoretical perspectives in education, and exposure to relevant skills. It was delivered by experienced facilitators and established academic leaders (and practitioners) in the academic health sciences.

기본 메커니즘(M1)

Primary mechanisms (M1)

협업-반사(또는 공동반사)

Collaborative-reflection (or co-reflection)

프로그램 활동은 참가자의 학업 관행에 영향을 미치는 실제 과제에 대한 지속적인 성찰 대화를 촉발했다. 참여자들은 능동적인 실무자active practictioner로서 서로의 경험 기반 지식에서 도출하고, 공유하고, 성찰할 수 있었다. 이러한 협업적 성찰 프로세스는 프로그램 참여자들에 의해 높이 평가되었습니다. 이들은 이 과정이 지속적인 통찰력과 지원의 원천이기 때문에 개발의 중심이라고 인식했습니다.

Program activities triggered ongoing reflective dialogue about real-life challenges affecting participants’ academic practices. As active practitioners, participants could draw from, share, and reflect upon each other’s experience-based knowledge. This process of collaborative reflection was highly valued by programparticipants; they perceived it as central to their development as it was a source of ongoing insight and support.

자기반성 및 자기조절

Self-reflection and self-regulation

또한 프로그램 활동은 종종 참가자들의 교육 관행, 역할, 직업 야망, 개인적 목표와 관련하여 자아에 대한 조사를 필요로 했기 때문에, 이 프로그램은 내면의 성찰introspective reflection을 불러일으켰다. 결과적으로, 참여자들은 얻은 통찰력에 따라 행동하기 위해 개인적인 행동을 규제하거나 수정할 수 있다.

The program also triggered introspective reflection, as programactivities often necessitated examination of participants’ sense of self in relation to their educational practices, roles, career ambitions, and personal goals. In turn, participants could regulate or modify personal behaviours in order to act upon insights gained.

관계구축

Relationship building

프로그램의 과정을 통해, 계속되는 사회적 상호 작용은 참가자 사이의 개인적, 직업적 관계 모두의 발전을 촉진시켰다. 결과적인 사회적 제휴는 지속적인 지원과 향후 협력 이니셔티브의 기반을 형성했습니다.

Through the course of the program, ongoing social interactions facilitated the development of both personal and professional relationships, among participants. The resulting social affiliations formed the basis for ongoing support and future collaborative initiatives.

다양한 형태의 학습을 통한 교육학적 지식 습득

Pedagogical knowledge acquisition through various forms of learning

참가자들은 교육 이론과 실제에 대한 지식 습득을 보고했습니다.

Participants reported the acquisition of knowledge about educational theory and practice.

이러한 지식 습득은 다양한 형태의 학습을 통해 발생할 가능성이 높지만, 많은 참가자들이 관찰 학습을 개발의 중심이라고 보고했다.

Although this knowledge acquisition likely occurred through various forms of learning, many participants reported observational learning as central to their development.

결과(O)

Outcomes (O)

개별 결과(OI)

Individual outcomes (OI)

참가자들은 태도, 지식 및 업무 역할의 몇 가지 변화를 프로그램에 참여하기 때문이라고 설명했습니다. 일부 교수들은 자신들의 역할에 대한 불안이 덜하다고 보고했다. 많은 사람들이 더 박식하고 숙련되었다고 느꼈다. 이와 관련, 대부분이 교육자와 지도자로서 자신감과 자기효능감이 더 높다고 보고했습니다. 그 자료는 또한 교수들 사이의 더 강한 학문적 정체성과 그들의 역할에서 더 높은 의미와 목적 의식을 강조했습니다. 몇몇 졸업생들은 또한 고위직으로 승진했는데, 그들은 이 프로그램을 완성한 것과 거기서 얻은 이득이 그들의 덕이라고 그들은 말했다.

Participants attributed several changes in attitudes, knowledge, and work roles to their participation in the program. Some faculty reported less anxiety in their roles. Many felt more knowledgeable and skilled. Relatedly, most reported greater confidence and selfefficacy as both educators and leaders. The data also highlighted a stronger sense of academic identity among faculty and an enhanced sense of meaning and purpose in their roles. Several graduates also received promotions to senior roles, which they attributed to their completion of the program and gains made therein.

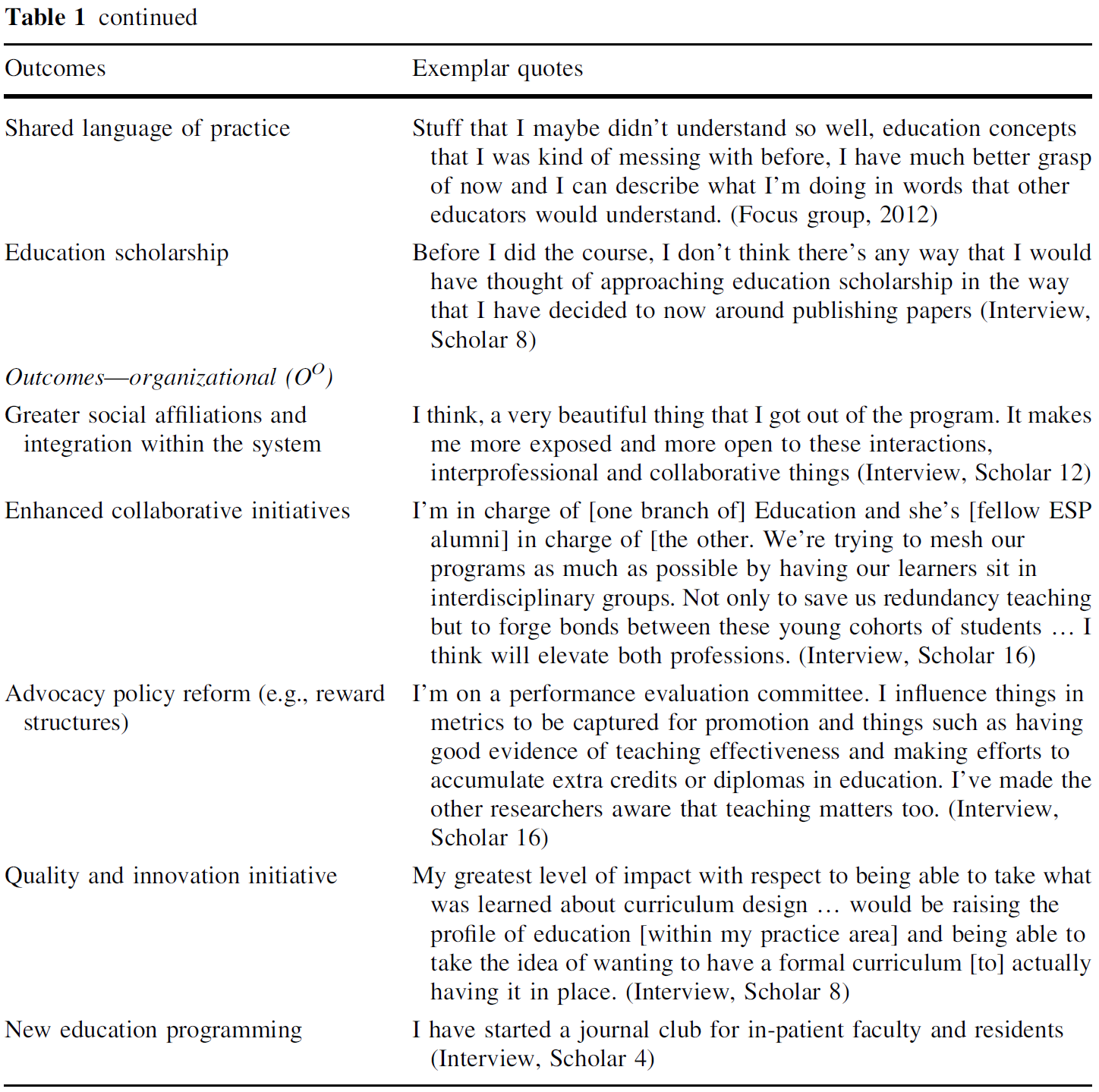

교육 실무 결과(OE)

Educational practice outcomes (OE)

참가자들은 프로그램 참여의 기능으로서 교육 관행에 대한 몇 가지 긍정적인 변화를 보고했다. 여기에는 피드백, 학습자 관련, 교사 평가 수행을 포함한 교사의 수정이 포함되었습니다. 많은 사람들은 그들의 교육 관행이 일반적으로 더 이론적으로 알려졌다고 믿었다. 이것이 나타난 방법 중 하나는 다른 교육자들과의 공유된 실천 언어를 채택하는 것이었는데, 이는 프로그램 동안 습득한 교육 개념과 이론에 해당된다.

Participants reported several positive changes to their educational practices as a function of program participation. These included modifications to their teaching, including giving feedback, relating with learners, and performing teacher evaluations. Many believed their educational practices were generally more theoretically informed. One of the ways this manifested was in the adoption of a shared language of practice with other educators, corresponding to educational concepts and theories acquired during the program.

대부분의 참가자들은 교육 학술활동에 대한 참여도가 상당히 높다고 보고했습니다. 예를 들어, 참가자들은 연구를 수행하고 연구 결과를 배포했습니다. 또한, 교수진들은 학부 내에서 교육자로서 더 높은 신뢰도를 가지고 있다고 보고했습니다. 실제로, 많은 졸업생들이 상담역할을 맡아 업무 부서 내에서 다양한 교육 이니셔티브에 대한 조언과 리더십을 찾고 있는 동료들의 핵심 연락 담당자로 활동했다고 보고했다.

Most participants reported significantly greater engagement in educational scholarship; for instance, participants conducted research and disseminated their findings. Additionally, faculty reported having greater credibility as educators within their academic units. Indeed, many graduates reported functioning in consultative roles, serving as key contact persons for their peers who sought them out for advice and leadership on a range of educational initiatives within their work units.

조직 결과(OO)

Organizational outcomes (OO)

보고된 많은 결과는 개인을 뛰어넘는 결과를 낳았다. 많은 교수진들은 교육 기관이 프로그램이 완료되는 대로 업무 단위 내에서 지속되온 학업 관행academic practice을 변경하도록 하는 것을 기술했다. 이것은 두 가지 방법으로 증명되었다.

- 첫째, 참여자들은 교육 및 커리큘럼 개발 실무에 대한 품질 개선을 권고하고 제정enact했으며, 관련 혁신을 지원했다.

- 둘째, 참가자들은 향상된 신뢰성과 위치적positional 힘을 이용하여, [교육자에게 불이익을 주고 교육 관행을 저해할 수 있는] (기존의) 학문적 보건 과학 내의 시스템에 보상을 주는 개혁을 지지했다.

Many reported outcomes had implications that extended beyond the individual. Many faculty described having the agency to make changes to ongoing academic practices within their work units, upon completion of the program. This was manifested in two ways.

- One, participants recommended and enacted quality improvements to teaching and curriculum development practices, and supported relevant innovations.

- Two, participants took advantage of enhanced credibility and positional power to advocate for reform to reward systems within the academic health sciences that may disadvantage educators and undermine educational practice.

또한, 프로그램 참여자와 졸업자는 학생, 주민 및/또는 교직원을 위한 다양한 커리큘럼의 개발과 개정에 기여하고 선도하는 것으로 보고되었다. 거의 모든 프로그램 졸업생들이 졸업과 동시에 훨씬 더 큰 교육자 네트워크의 일부라고 보고했다. 그들은 직업적, 지역적 경계에 걸쳐 더 큰 사회적 연대를 구축했다고 묘사했다.

Furthermore, program participants and graduates reported contributing to, and leading, the development of programs and revision of various curricula for students, residents, and/or faculty. Nearly all programgraduates reported being part of a much larger network of educators upon graduation. They described having established greater social affiliations across professional and locational boundaries.

보조 메커니즘(M2)

Secondary mechanisms (M2)

심리적, 구조적 권한 부여

Psychological and structural empowerment

우리는 [프로그램 졸업자의 행위자성]이 [직장에서의 변화를 집행하게 되는 기초적인 권한 부여 패턴]을 알아냈다. 우리는 이 권한 부여를 부분적으로는 본질적(심리적)으로, 부분적으로는 조직 내의 신흥 권력(구조적)에서 파생되는 것으로 개념화했다. 예를 들어, 한 참가자는 [자신의 교육 학술사업의 동인]으로서의 시스템 내에서 '적절한 사람'을 가진 [신흥emerging 전문 네트워크뿐만 아니라 [영감과 동기부여]를 모두 인정하였다.

We identified a pattern of empowerment underlying program graduates’ agency to enact changes in the workplace. We conceptualized this empowerment as partly intrinsic (psychological) and partly derived from emerging power within one’s organization (structural). For example, one participant credited both inspiration and motivation, as well as emerging professional networks with the ‘right people’ within the system as drivers of his/her educational scholarship work.

프로그램 참여에 의해 촉진된 [주요 직책에 있는 사람들과의 관계]는 프로그램 졸업생들이 다양한 의제를 추진하는 데 도움을 준 비공식적이기는 하지만 중요한 힘의 원천이었다.

Relationships with people in key positions, some of which were facilitated by program participation, were a critical, albeit informal, source of power that helped program graduates drive various agenda forward.

반대로, 소외감을 느끼거나 동료를 참여시킬 수 없는 상황에서 일하는 프로그램 졸업생들은 무력감을 느꼈다.

Conversely, program graduates who worked in contexts where they felt isolated or unable to engage peers felt disempowered.

[공식적인 리더십 직책]도 구조적 권한 부여의 원천이었고, 공식적인 리더십 직함이 없는 경우, 어떤 경우에는 강력한 위치에 있는 개인과의 관계에서도 참여자들의 의사일정 추진 능력이 제한되기도 했다.

Formal leadership positions were also a source of structural empowerment, and the absence of a formal leadership title, in some cases, limited participants’ capacity to drive an agenda forward, even in the presence of relationships with individuals in powerful positions.

시스템(학술 건강 과학) 컨텍스트(C2)

System (academic health sciences) context (C2)

고위 리더십 지원

Senior leadership support

(교직원에게 책임이 있는) [시니어 리더의 우선 순위와 지원]은 교수진 개발에서 더 넓은 이익을 실현할 수 있는 여러 참가자들의 능력에 상당한 영향을 미쳤다. 시니어 리더의 지원을 받지engage 못한 참가자는 지식 습득물을 전이tranfer할 수 있는 능력이 제한되었습니다.

The priorities and support of senior leadership (to whom faculty were accountable) had a significant impact on the capacity of several participants to realize the broader benefits from faculty development. Participants unable to engage the support of senior leadership, were limited in their capacity to transfer knowledge gains:

제가 그 이야기를 시작했는데, 눈을 돌렸을 때 그의 눈빛이 흔들리는 것을 들은 것 같아요. 당신이 팔고 있는 물건을 사지 않는 사람으로부터 설명하기는 어렵죠. (포커스 그룹 2011, 그룹 3)

I started talking about it and I think I heard his eyes rolling when I looked away… it’s difficult to explain from somebody who’s not buying what you’re selling. (Focus Group 2011, group 3)

다른 프로그램 졸업생들은 교육 활동을 낮은 우선순위로 강등시킨 고위 지도자들 밑에서 일했다.

Other program graduates worked under senior leaders who relegated educational activities to a low priority status.

교육 역할은 기본적으로 아무런 논의 없이 그녀가 원하는 역할이 전혀 아니라고 판단했을 뿐이며, 또한 그녀는 내가 점차적으로 자금을 대던 것에서 자금을 빼앗아갔다(인터뷰, 스콜라 4).

The education role basically, without any discussion, she just decided that that was not a role that she wanted continued at all… And also she has taken away funding from things that I had gradually gained funding for (Interview, Scholar 4)

리소스 가용성

Resource availability

[시간과 재정 자원]은 프로그램 졸업생의 의도와 교수진 개발로 얻는 이익을 실무에 통합하려는 능력에 중요한 영향을 미쳤다. 교육 수요와 임상 의무, 일과 삶의 균형, 그리고/또는 보장 보상의 충돌이 빈번했다. 또한, 연구 및 새로운 프로그래밍을 위한 자금 확보 경쟁이 치열했습니다. 자금 확보는 성공에 매우 중요했습니다.

Time and financial resources were key influences on program graduates’ intention and capacity to incorporate gains from faculty development within their practice. Conflicts between educational demands and clinical duties, work-life balance, and/or secure compensation were frequent. In addition, competition for funding for research and new programming was tough; securing funds was critical to success.

지역 사회 참여

Community engagement

졸업생들은 성공적인 변화 이니셔티브를 도입하기 위해 [기관 내 다른 이해 관계자들의 참여]가 필요하다고 설명했습니다. 이러한 이해당사자들은 참여가 필요한 학생일 수도 있고, 집단적 의사결정에 있어 지원이 필수적인 동료일 수도 있다. 이해당사자들의 참여가 항상 다가오는 것은 아니었고, 프로그램 졸업생들은 종종 교육 관행을 강화하려는 노력에 대한 반발에 부딪혔다.

Graduates described needing the engagement of other stakeholders within their institutions, in order to introduce successful change initiatives. These stakeholders could be students whose participation was needed, or peers whose support was essential for collective decision-making. Stakeholder engagement was not always forthcoming, and program graduates frequently encountered resistance against their efforts to enhance educational practices.

지역사회의 필요성

Community needs

데이터 세트에서 우리는 [(다양한 작업 단위 내에서) 떠오르는emergent 요구에 대한 대응성]의 반복적인 테마를 식별했다. 프로그램 졸업생들은 종종 그들의 학계 내의 다양한 요구에 부응하는 [교육 이니셔티브를 주도하거나 지원할 기회를 제공받거나 모색해야만] 했다.

Across the data set we identified the recurrent theme of responsiveness to emergent needs within various work units. Program graduates often needed to be presented with, or to seek out, opportunities to lead or support educational initiatives that addressed various needs within their academic community.

고찰

Discussion

결과 개요

Overview of findings

현존하는 이론과 문헌에 비추어 볼 때 CMO 관계

CMO relationships in light of extant theory and literature

프로그램 컨텍스트의 특정 기능은 시간, 안전한 공간, 교육학적 지식의 노출 및 사회적 상호 작용의 다중 수단과 같은 다중 변경 메커니즘을 생성하는 데 도움이 되는 공간을 만드는 데 매우 중요했다. 그 자체와 내부에서의 이러한 발견은 놀랄만한 것이 아니다. 그러나 만달라의 주목할 만한 기여는 프로그램 컨텍스트, 메커니즘 및 더 넓은 컨텍스트의 분리할 수 없는 계층들 사이의 상호 작용을 입증하는 것이다. 커리큘럼 내용에 대한 노출은 참가자의 지식 획득을 자극할 수 있지만, 다른 상황적 특성은 개별 학습을 넘어 이 프로세스를 지원하고 변화 메커니즘을 촉발하는 데 중요하다.

Certain features of the program context were critical to creating a space conducive to generating multiple change mechanisms: time, a safe space, exposure to pedagogical knowledge, and multiple means of social interaction. These findings in and of themselves are unsurprising. But a notable contribution of the mandala is its demonstration of the interactions among inextricable layers of program context, mechanisms, and broader contexts. Whereas exposure to curricular content can spark participants’ acquisition of knowledge, other contextual features are critical to supporting this process and triggering change mechanisms beyond individual learning.

예를 들어, [교육에 집중하는 시간의 보호]는 전문적 발전에 필수적인 것으로 간주되었다. 이러한 상황적 전제 조건이 없을 때, 프로그램 활동에 대한 의미 있는 참여가 제한되었고 다른 메커니즘이 억제되었다. 기존 연구는 학습을 위한 [전용dedicated 시간]을 집단 학습, 성찰, 장학금 및 리더십 개발에 매우 중요한 시간으로 식별한다(Rushmer 등). 2004; Zibrowski 등 2008).

For instance, the protection of time to focus on education was deemed essential for professional development; when this contextual precondition was absent, meaningful participation in program activities was constrained and other mechanisms were inhibited. Existing research identifies dedicated time for learning as critical for collective learning, reflection, scholarship and leadership development (Rushmer et al. 2004; Zibrowski et al. 2008).

교수진 개발 학습 공간의 [안전 인식perceived safety]도 변화 메커니즘을 가능하게 했다. 실제로, 안전한 교육 환경은 학습자가 실험, 음성 우려, 불확실성 인식 및 한계 확장을 충분히 편안하게 느낄 수 있는 선생님과 학습자 사이의 상호 신뢰 공간으로 특징지어졌다(허친슨 2003; 영 외 2015).

The perceived safety of the faculty development learning space was also an enabler of change mechanisms. Indeed, safe educational environments have been characterized as spaces of mutual trust between teachers and learners, where learners feel comfortable enough to experiment, voice concerns, acknowledge uncertainty, and stretch limits (Hutchinson 2003; Young et al. 2015).

[교수진이 사회적 또는 정치적 파장을 두려워하지 않고 시스템적 과제를 논의]할 뿐만 아니라 [정보와 창의적인 아이디어를 공개적으로 교환]할 수 있는 [프로그램 조건]은 확인된 변경 메커니즘을 가능하게 할 가능성이 더 높다. 마찬가지로, 프로그램 내에서 [사회적 상호 작용을 위한 지속적인 기회]는 관계적 및 협력적 변화 메커니즘에 필요한 기초를 제공한다.

Program conditions that allow faculty to openly exchange information and creative ideas, as well as discuss systemic challenges without fear of social or political repercussions, are more likely to enable the identified change mechanisms. Similarly, ongoing opportunities for social interaction within the program provide the necessary foundation for relational and collaborative change mechanisms.

첫째, [성찰 과정]은 사회적(협업적 성찰) 수준과 개인(자기 성찰) 수준 모두에서 교수진 개발의 결과물을 촉진하기 위한 핵심 메커니즘으로 식별되었다.

First, reflective processes were identified as key mechanisms for the facilitation of outcomes from faculty development, both at the social (collaborative-reflection) and individual (self-reflection) levels.

성찰과 관련된 건강 직업 교육의 대부분의 논문은 개인 지향 성찰에 초점을 맞춘다(Ng et al. 2015). 본 연구에서 주목할 만한 발견은 참여자들의 [협업과 자기 성찰]에 대한 가치였다. 성찰은 수행되거나 발생한 사건에 대한 검사가 새로운 이해와 감사로 이어질 수 있는 지적 및 정서적 활동을 구성하는 인지 과정으로 설명되었다(2001년 Boud).

Most papers in health professions education relating to reflection focus on individually-oriented reflection (Ng et al. 2015); a notable finding in this study was participants’ valuing of both collaborative and self-reflection. Reflection has been described as a cognitive process, comprising intellectual and affective activities in which examination of actions performed, or incidents encountered, can lead to new understanding and appreciation (Boud 2001).

협력적 성찰(공동-성찰)은 [새로운 주관적 이해와 감사appreciated에 도달하기 위한 통찰력과 경험의 상호 공유를 촉진하기 위해, 둘 이상의 사람 사이의 인지적 및 정서적 상호작용을 포함하는 공유된 비판적 사고 과정]으로 정의되었다(Yukawa 2006). 실무자 그룹을 한데 모으는 전문 개발 프로그램 활동은 실제 과제에 대한 협업적 성찰을 위한 사회적 기반을 구축할 수 있다(Watkins et al. 2011).

Collaborative-reflection (co-reflection) has been defined as a shared critical thinking process that involves cognitive and affective interactions between two or more people to facilitate mutual sharing of insights and experiences to reach new inter-subjective understandings and appreciations (Yukawa 2006). Professional development program activities that bring together groups of practitioners can establish a social foundation for collaborative reflection on real-life challenges (Watkins et al. 2011).

[공동성찰적 실천]은 공동성찰을 통해 그룹이 [경험을 공유하고 주장과 증거를 평가할 수 있을 뿐만 아니라 대안적 관점을 검토]할 수 있기 때문에, 리더십 개발 프로그래밍을 위한 중심 메커니즘으로 식별되었다(Lyso 2010; Watkins et al. 2011). 우리의 연구는 이러한 발견들과 일관되었고 아마도 '자신'을 넘어서는 성찰 연구를 계속할 가능성을 시사할 것이다.

Co-reflective practice has been identified as a central mechanism of change for leadership development programming (Lyso 2010; Watkins et al. 2011) because through co-reflection, a group can share experiences, weigh arguments and evidence, as well as examine alternative perspectives (Yukawa 2006). Our research was consistent with these findings and may suggest the potential to continue to study reflection beyond the ‘self.’

성찰과 관련된 또 다른 흥미로운 발견은 [자기 성찰과 자기 조절의 연계성]이었다. 자기 성찰은 다양한 공식 및 비공식 출처에서 발생할 수 있는 피드백 정보의 자기성찰적 분석을 포함한다(Moon 2004). (Ashford 2003; Moon 2004; Nesbit 2012) 이 연구에서, 이 프로그램은 자신의 교육 관행, 직업 야망 및 개인적 목표와 관련하여 내향적으로 분석될 수 있는 지속적인 다중 소스 피드백의 풍부한 소스를 제공하였다.

Another interesting finding related to reflection was the linked nature of self-reflection and self-regulation. Self-reflection involves introspective analysis of feedback information (Moon 2004), which can arise from a variety of formal and informal sources (Ashford 2003; Moon 2004; Nesbit 2012). In this study, the program provided a rich source of ongoing, multi-source feedback that could be analysed introspectively in relation to one’s own educational practices, career ambitions, and personal goals.

우리의 연구 결과에서, 자기조절은 (자기조절의) 적극적인 동반자로서 자기 반성과 짝을 이루었다. 기존 문헌은 [오랜 시간에 걸친 목표 지향적 활동을 향한 자기 성찰의 통찰력을 안내guide하는 것]이 자기 조절의 과정이라고 말한다. (Karoly 1993) 궁극적으로, 지속적인 자기조절은 변화하는 환경 환경에 대한 지속적인 적응뿐만 아니라 행동 전략의 개발, 새로운 행동의 채택 및 유지를 가능하게 한다(Nesbit 2012).

In our findings, self-regulation was paired with self-reflection as its active companion. Extant literature states that it is the process of self-regulation that guides the insights of self-reflection towards goal directed activities over time (Karoly 1993). Ultimately, ongoing self-regulation allows for the development of action strategies, adoption and maintenance of new behaviours as well as ongoing adaptation to changing environmental circumstances (Nesbit 2012).

마지막으로, [관계 구축]은 또한 주요 1차 변화 메커니즘으로 식별되었다. 이 프로그램은 전문직 및 조직 경계를 넘어 대학 관계를 발전시키고 육성하기 위한 플랫폼을 제공하였다. 이러한 관계는 후속 협업 이니셔티브 및 전문 지원 네트워크의 토대를 마련합니다.

Finally, relationship building was also identified as a key primary change mechanism. The program provided a platform for development and nurturing of collegial relationships across professional and organizational boundaries. These relationships set the foundation for subsequent collaborative initiatives and professional support networks.

우리의 통합 이론 기반 평가 접근 방식을 통해 우리는 어떻게 1차 변화 메커니즘과 단기 결과가 더 오랜 기간에 걸쳐 펼쳐지는 [2차 변화 메커니즘]의 발판을 마련할 수 있는지 탐구할 수 있었다. 우리는 [권한 부여 프로세스Empowerment process]를 프로그램과 제도적 맥락에 걸친 CMO 상호 관계의 융합에 의해 촉발된 주요 2차 변경 메커니즘으로 식별했다. [임파워먼트]는 두 가지로 개념화되었다 - 심리적, 구조적.

Our integrated theory-based evaluation approach allowed us to explore how primary change mechanisms and short term outcomes can set stage for secondary change mechanisms that unfold over a longer time period. We identified empowerment processes as key secondary mechanisms of change, triggered by a confluence of CMO interrelationships across program and institutional contexts. Empowerment has been conceptualized as both psychological (Spreitzer 1995a; Thomas and Velthouse 1990) and structural (Kanter 1993; Laschinger et al. 2001, 2004).

[심리적 권한 부여]는 개인이 업무 역할 또는 상황에 영향을 미칠 수 있는 내재적 동기 부여 수단이다(Spreitzer 1995a; 토머스와 벨하우스 1990). 자신의 작업에 대한 의미, 역량 및 효과를 포함하여 본 연구에서 확인된 특정 개인 수준 결과와 경험적으로(긍정적으로) 연결되었다(Spreitzer 1995a, 1995b, 2009).

Psychological empowerment is an intrinsic motivational vehicle through which individuals can affect their work roles or context (Spreitzer 1995a; Thomas and Velthouse 1990). It has been empirically (positively) linked to specific individual-level outcomes identified in this research including a sense of meaning, competence, and efficacy about one’s work (Spreitzer 1995a, 1995b, 2009).

[심리적 권한 부여]에 관계없이, [조직 구조]는 개인이 다양한 목표를 달성하지 못하게 할 수 있다(Kanter 1993). 구조적 권한 부여는 공식적(재량적 의사 결정력) 또는 비공식적(소셜 네트워크)일 수 있으며 기회, 자원, 정보 및 지원에 대한 [접근(권한)]에서 도출된다(Kanter 1993; Laschinger et al. 2001, 2004).

Regardless of psychological empowerment, organizational structures can (dis)empower individuals from achieving various goals (Kanter 1993). Structural empowerment can be formal (discretionary decision making power) or informal (social networks) and is derived from access to opportunities, resources, information, and support (Kanter 1993; Laschinger et al. 2001, 2004).

우리의 연구는 교수 개발 컨텍스트(C1)가 중요한 정보(예: 교육학 전문 지식)에 대한 액세스를 촉진하고 관계(M1)의 개발과 전문 지원 네트워크(OO)의 구축을 가능하게 하거나 재량적인 의사 결정력으로 공식적인 리더십 역할(OI)의 확보에 도움이 될 수 있음을 보여준다.

Our research shows that the faculty development context (C1) can be instrumental in facilitating access to critical information (e.g., pedagogical expertise), enabling development of relationships (M1) and the establishment of professional support networks (OO) or securement of formal leadership roles (OI) with discretionary decision making power.

기존 연구는 [심리 및 구조적 권한 부여]를 의료 환경에서 혁신적 행동과 긍정적으로 연결했다(Knol 및 Van Linge 2009). 권한 부여는 또한 직무 수행과 긍정적인 관련이 있다. 따라서 [심리적 및 구조적 권한 부여]가 change agency를 지원하는 역할을 할 수 있으며, 교수진이 제도적 맥락(C2)에 영향을 미치도록 뒷받침된다.

Existing research has linked psychological and structural empowerment positively to innovative behaviour in health care environments (Knol and Van Linge 2009). Empowerment is also positively related to job performance (Butts et al. 2009). Thus both psychological and structural empowerment can act to support change agency, with faculty bolstered to influence the institutional context (C2).

교수진 개발에 미치는 영향

Implications for faculty development

첫째, 우리의 발견은 유용한 기관(C2)과 프로그램 맥락(C1) 내에서, 교수진 개발이 개별 교수진과 그 기관 모두에 대해 긍정적인 결과(O)를 생성하는 일차 메커니즘(M1)을 촉발할 수 있음을 보여준다. 시간이 지남에 따라 이러한 결과와 관련 CMO 상호관계의 일관성은 추가 결과를 촉진하는 2차 메커니즘(M2)을 생성할 수 있다. 보고된 결과의 폭은 교수개발의 영향을 받을 수 있는 학술적 보건 과학 시스템 내의 기능이 [광범위]하다는 것을 강조한다. 교수개발은 교육역량을 높일 수 있는 잠재력이 있을 뿐만 아니라, 교육혁신과 학술개혁의 최전선에서 교육지도자 네트워크를 형성하며 변화의 주체이자 지역사회 지도자로서 교직원의 발전을 도울 수 있다. 따라서 교수 개발자는 교수 개발 프로그램을 모범 사례의 보루bastions로서 유지하는 것에 대한 책임감을 가져야 한다. 즉, 전달된 교훈lesson conveyed이 미래의 학술 보건 과학 시스템에 대한 높은 기준과 긍정적인 이상을 반영하도록 보장해야 한다.

First, our findings show that, within conducive institutional (C2) and program contexts (C1), faculty development can trigger primary mechanisms (M1) that generate positive outcomes (O) for both individual faculty and their institutions. Over time, the confluence of these outcomes and associated CMO interrelationships can generate secondary mechanisms (M2) that spur further outcomes. The breadth of reported outcomes underscores the broad span of functions within the academic health sciences system that can be influenced by faculty development. Not only does faculty development have the potential to enhance pedagogical competence, it can also aid the development of faculty as agents of change and community leaders, forming networks of education leaders at the forefront of curricular innovation and academic reform. Faculty developers should thus espouse a sense of responsibility for maintaining faculty development programs as bastions of best-practices—ensuring that the lessons conveyed reflect high standards and positive ideals for the academic health science systems of the future.

둘째, 이번 결과는 교수개발의 전달에서 실무 문제를 검토하는 데 유용한 모델을 제공한다. 이 모델은 원하는 목표나 영향을 달성하기 위해 어떤 일이 일어나야 하는지, 그리고 어떤 더 광범위한 상황적 특징을 고려해야 하는지에 대한 몇 가지 사양을 제공한다. 프로그램 제작자가 [자신이 성취하고 있다고 가정하는 것]과 [실제로 그 과정에서 어떤 변화가 펼쳐지는지] 사이의 연결고리를 검토할 수 있게 한다.

- 교수 개발자는 예를 들어 중요한 메커니즘이 전개될 수 있는 컨텍스트를 만들 때 효과성에 의문을 제기할 수 있다. 그들은 프로그램이 기대치를 충족시키지 못하거나 능가할 수 있는 영역에 대한 표적 검사를 수행하여 프로그램 구성요소가 예상대로 작동하는지 여부를 탐색할 수 있다.

- 그들은 또한 그들의 조직에서 [교수진의 행위자성]을 제약할 수 있는 권한의 부족을 상쇄하기 위한 방법을 찾기 위해 노력할 수 있다.

- 또한, 이론 기반 평가는 [이론 기반 프로그램 계획]으로 확장될 수 있다. 프로그램 설계 및 전달 전략의 개정을 알리기 위해 평가 결과를 프로그램 개발에 다시 입력한다.

- 마지막으로, 우리는 많은 교수진 개발 평가 노력을 특징짓는 [단기주의short-termism]를 피하기 위해 노력하고 경험적으로 확립된 연계를 활용하여 미래의 학술활동에 inform할 수 있다.

Second, the results provide a useful model for examining practice issues in the delivery of faculty development. The model provides some specification of what needs to happen, and what broader contextual features need to be considered, in order for desired goals or impact to be achieved. It allows for the examination of links between what program creators assume they are accomplishing, and what changes actually unfold along the way.

- Faculty developers can question their effectiveness in creating contexts where critical mechanisms can unfold, for example. They can explore whether program components work as expected by conducting targeted examination of areas where the program may excel or fails to meet expectations.

- They can also strive to find ways to offset the lack of empowerment that may constrain faculty agency in their organizations.

- Furthermore, theory-based evaluation can be expanded to theory-informed program planning (Baldwin et al. 2004) where results of evaluation are fed back into program development to inform revision of program design and delivery strategies.

- Finally, we can strive to avoid the short-termism that characterizes many faculty development evaluation efforts and draw on empirically established links to inform future scholarship.

장점과 한계

Strengths and limitations

마지막으로, CMO 관계의 원형 설명 모델은 종적 교수 개발 프로그래밍에서 일어나는 일에 대한 불완전한 표현일 수 있다. 실제로, "모든 모델은 잘못되었고, 일부는 유용하다"라고 말해왔다(Box and Draper 1987). 교수진 개발에서 지속적인 평가 노력을 위한 유용한 플랫폼을 제공하여 이론 기반 평가의 원칙적 목표 중 하나를 달성하는 것이 우리의 목표이다.

Finally, our circular illustrative model of CMO relationships may be an incomplete representation of what happens within longitudinal faculty development programming. Indeed, it has been said that ‘‘all models are wrong, some are useful’’ (Box and Draper 1987). It is our goal to provide a useful platform for ongoing evaluative efforts in faculty development, thus fulfilling one of the principle aims of theory-based evaluation.

Adv Health Sci Educ Theory Pract

. 2017 Mar;22(1):165-186.

doi: 10.1007/s10459-016-9690-9. Epub 2016 Jun 13.

A mandala of faculty development: using theory-based evaluation to explore contexts, mechanisms and outcomes

Betty Onyura 1, Stella L Ng 2 3 4 5 6, Lindsay R Baker 2 7, Susan Lieff 2 8, Barbara-Ann Millar 2 9, Brenda Mori 2 10

Affiliations collapse

Affiliations

-

1Centre for Faculty Development, Faculty of Medicine, Li Ka Shing Knowledge Institute, University of Toronto at St. Michael's Hospital, 4th Floor, 209 Victoria Street, Toronto, ON, M5B 1W8, Canada. onyurab@smh.ca.

-

2Centre for Faculty Development, Faculty of Medicine, Li Ka Shing Knowledge Institute, University of Toronto at St. Michael's Hospital, 4th Floor, 209 Victoria Street, Toronto, ON, M5B 1W8, Canada.

-

3Department of Speech-Language Pathology, University of Toronto, Toronto, ON, Canada.

-

4Centre for Ambulatory Care Education, Women's College Hospital, Toronto, ON, Canada.

-

5Rehabilitation Sciences Institute (RSI), University of Toronto, Toronto, ON, Canada.

-

6The Wilson Centre, Faculty of Medicine, University of Toronto at University Health Network, Toronto, ON, Canada.

-

7Li Ka Shing Knowledge Institute, St. Michael's Hospital, Toronto, ON, Canada.

-

8Department of Psychiatry, Faculty of Medicine, University of Toronto, Toronto, ON, Canada.

-

9Department of Radiation Oncology, Faculty of Medicine, University of Toronto, Toronto, ON, Canada.

-

10Department of Physical Therapy, Faculty of Medicine, University of Toronto, Toronto, ON, Canada.

-

PMID: 27295217

Abstract

Demonstrating the impact of faculty development, is an increasingly mandated and ever elusive goal. Questions have been raised about the adequacy of current approaches. Here, we integrate realist and theory-driven evaluation approaches, to evaluate an intensive longitudinal program. Our aim is to elucidate how faculty development can work to support a range of outcomes among individuals and sub-systems in the academic health sciences. We conducted retrospective framework analysis of qualitative focus group data gathered from 79 program participants (5 cohorts) over a 10-year period. Additionally, we conducted follow-up interviews with 15 alumni. We represent the interactive relationships among contexts, mechanisms, and outcomes as a "mandala" of faculty development. The mandala illustrates the relationship between the immediate program context, and the broader institutional context of academic health sciences, and identifies relevant change mechanisms. Four primary mechanisms were collaborative-reflection, self-reflection and self-regulation, relationship building, and pedagogical knowledge acquisition. Individual outcomes, including changed teaching practices, are described. Perhaps most interestingly, secondary mechanisms-psychological and structural empowerment-contributed to institutional outcomes through participants' engagement in change leadership in their local contexts. Our theoretically informed evaluation approach models how faculty development, situated in appropriate institutional contexts, can trigger mechanisms that yield a range of benefits for faculty and their institutions. The adopted methods hold potential as a way to demonstrate the often difficult-to-measure outcomes of educational programs, and allow for critical examination as to how and whether faculty development programs can accomplish their espoused goals.

Keywords: Faculty development; Program evaluation; Realist evaluation; Theory-based evaluation.

'Articles (Medical Education) > 교수개발(Faculty Development)' 카테고리의 다른 글

| 다시잡아두기: 어떻게 교육자가 상충하는 요구의 바다속에서 정체성을 유지하는가(Acad Med, 2019) (0) | 2021.02.10 |

|---|---|

| 임상교사 되기: 맥락 속에서의 정체성 형성(Acad Med, 2019) (0) | 2021.02.10 |

| 보건전문직 교수개발에서 어떻게 문화가 이해되는가: 스코핑 리뷰(Acad Med, 2020) (0) | 2021.02.07 |

| 임상교육자에서 교육적 학자, 그리고 리더: HPE분야에서 커리어 개발(Clin Teach, 2020) (0) | 2021.02.07 |

| 왜 우리는 교사를 가르쳐야 하는가? 임상감독관의 학습 우선순위 확인(Adv in Health Sci Educ, 2018) (0) | 2021.02.05 |